Democrats, I Implore You: Stop It

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

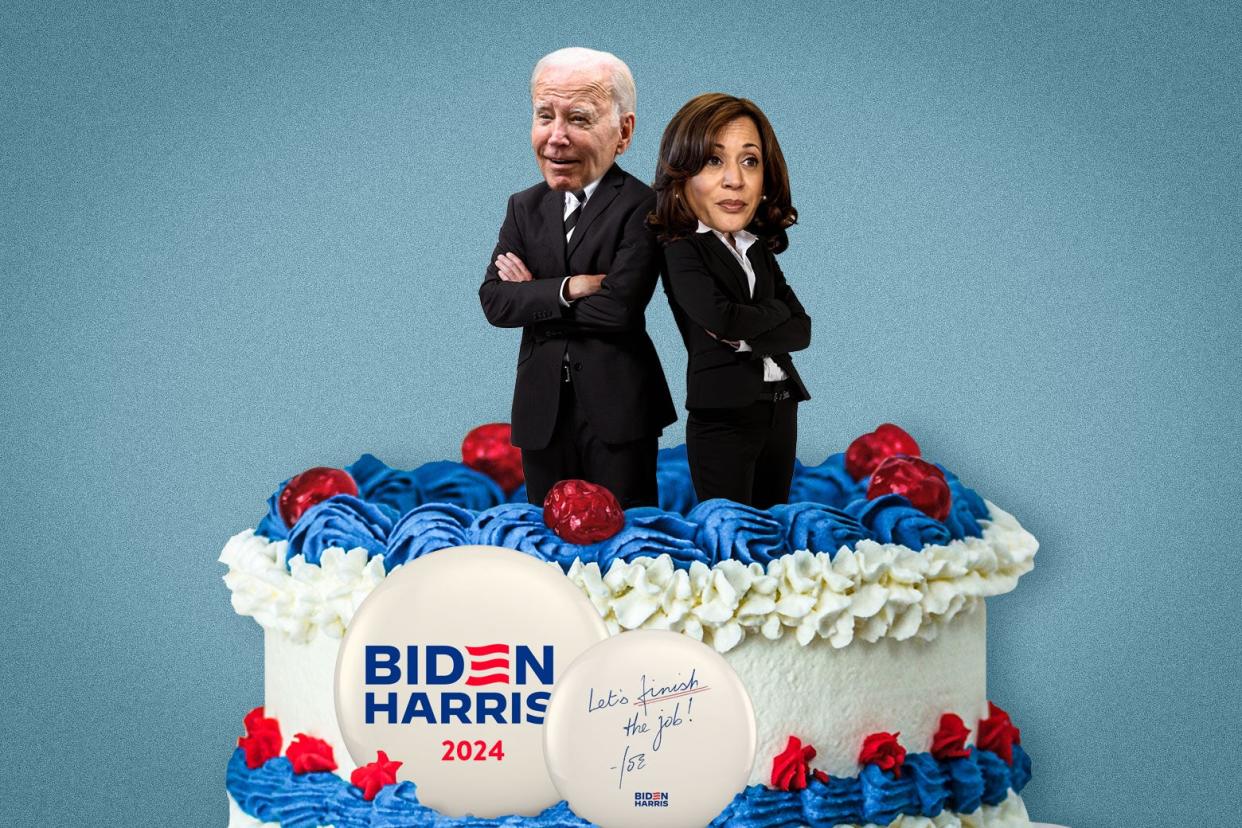

A slow late-summer news cycle has brought us fresh pontification about how President Biden, still battling gruesome polling and growing concerns about his age and appeal, should inject new life into his campaign by picking a new running mate for 2024. Like most recommendations brought to us by op-ed columnists with too much time on their hands, casting Kamala Harris aside is a dreadful idea—not only because it has almost zero chance of actually happening, but because it would clearly cause more problems than it would solve.

“Maybe the president should dump the veep” is a Beltway parlor game as old as time. Or at least as old as the writers doing the speculating. There were calls for George H.W. Bush to replace Dan Quayle with Colin Powell in 1992, and gossip that George W. Bush would toss the gruff Dick Cheney overboard in 2004. Before the 2012 election, some thought that Barack Obama, reeling from his historic “sh ellacking” in the 2010 midterms, should eighty-six then–Vice President Biden and replace him with his 2008 rival, Hillary Clinton. In 2019, D.C. was rife with rumors that Mike Pence would be sacked as Trump’s running mate for former U.N. Ambassador and South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley.

Not to give away the ending to Titanic here, but none of these incumbents cashiered their vice presidents. No elected incumbent in the binding primary era that began in 1972 has switched running mates before standing for reelection, and the last time it happened at all was in 1944, when Harry Truman replaced Henry Wallace on the ballot to be FDR’s vice president—and then that was only because he had made too many ideological enemies inside the Democratic Party to stay, a problem Harris does not have. And while Gerald Ford, whose journey to the presidency was highly unusual, picked Bob Dole in 1976, and not incumbent Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, that was because Rockefeller made it clear he had no interest in the job.

If Democrats could wave a magic wand and replace Harris with someone like Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, as New York magazine’s Eric Levitz suggests, without the ensuing backlash and “Democrats in disarray” news cycles, would that be a good idea? Possibly. (Not so much for Washington Post columnist David Ignatius’ bananas idea to swap in Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who was for a time the least popular governor in America.) But there are no magic wands in politics—only unappealing options and constraints imposed by choices made in the past, what social scientists call “path dependence.” The moment Biden selected Harris as his partner in 2020, he all but ensured that she would be more or less irreplaceable.

There were good reasons that the presidents who flirted briefly with shaking things up in this fashion ultimately decided against it. For one thing, the choice of vice president has almost no bearing whatsoever on the election outcome, as political scientists have pointed out again and again, and each time there’s a new veepstakes. Running mates are usually chosen for strategic reasons, to placate a specific constituency or to assuage concerns about the head of the ticket. This is how we ended up with Biden as Obama’s running mate: An older, more experienced white man could fend off worries that Obama’s meager two years in the Senate and unusual background might prove to be a problem in the general election. But it is hard to imagine a core Democratic constituency that Biden can less afford to deliberately alienate than Black women, who gave the president an 81-point margin in 2020, according to exit polls—especially at a time when pollsters keep warning that turnout among voters of color is one of the president’s worst potential problems.

It is, of course, impossible to deny that Harris has liabilities, or deny that she has disappointed as both a presidential candidate and now as vice president. She’s been caught flat-footed too many times by what seemed like simple queries, and she has failed to stake out a clear policy space for herself inside the party. But Biden has done her no favors, either. He put her in charge of the southern border, an effectively impossible task given that Congress has shown zero interest in addressing the many problems there. Vice presidential popularity rises and falls with the president’s, and Biden’s numbers have been underwater since August 2021. According to Gallup, Harris had far better approval numbers at the time of her inauguration than Pence did. If Democrats are worried about her favorability ratings, they should remember that the best thing they could do for them is to somehow boost Biden’s.

What about worries that Harris will become the party’s de facto nominee in 2024, if something happens to Biden, or in 2028? I wouldn’t be so sure about that. Yes, current or former vice presidents who seriously seek their party’s nomination have rarely failed to get it. On the other hand, Harris has been well under 50 percent in polls that ask who Democratic primary voters would support if Biden doesn’t run again, and she would likely face an unusually stiff challenge in the primaries even if she somehow ascends to the presidency before next year.

One summer survey from the well-respected Ipsos/Reuters had her at just 20 percent among Democrats, only 7 points ahead of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg. She’s eminently beatable, and Democrats should trust their own voters to make the best choice. That said, after several years of seasoning at the national level, we might also find that Harris will be a much better candidate the next time around. And there is no telling how someone like Whitmer, or another popular governor, might handle the national spotlight. Just ask Ron DeSantis.

Rather than worrying about what Harris might do in 2028, Democrats would do well to imagine what she and her team might do if they get thrown under the bus, especially if they feel like they are taking the fall for the failings of the president himself. If you think cutting memoirs from random Cabinet secretaries are bad, imagine the tea that a spurned Harris and her team might spill about the inner workings of the Biden administration. There are probably more embarrassing stories to share than bitey German Shepherds and interminable slide shows over lunch.

So quit it: Vice President Harris isn’t going anywhere.