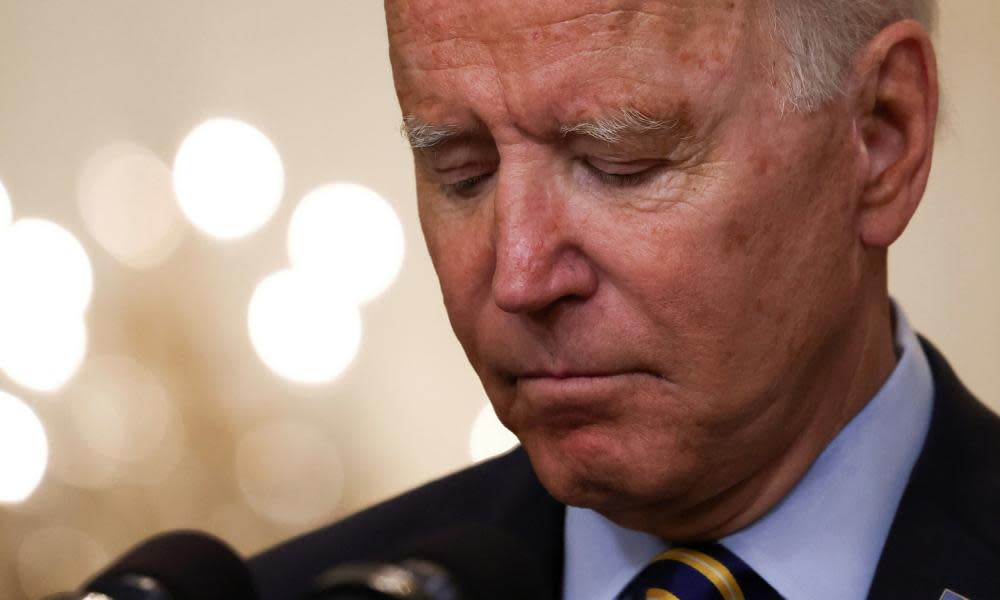

Biden in an impossible bind as Afghanistan blame game begins

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The words of political leaders can come back to haunt them. “None whatsoever, zero,” Joe Biden said last month when asked if he saw any parallels between the US withdrawals from Vietnam and Afghanistan.

“The Taliban is not the North Vietnamese army. They’re not remotely comparable in terms of capability. There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of the embassy of the United States from Afghanistan. It is not at all comparable.”

Related: Pentagon ‘deeply concerned’ by sweeping Taliban gains in Afghanistan

The dispatch of 3,000 extra US troops to help evacuate embassy staff looks like a pre-emptive move to avoid such a humiliating spectacle. Even so, with the Taliban on the march and closing in on Kabul, it did not stop cable news networks on Friday replaying grainy images from Vietnam nor the rightwing New York Post running the front page headline “Biden’s Saigon”.

A blame game away is under way for an issue that defies finger pointing, simple headlines or strident certainty perhaps more than any other. Biden is only the latest American president to stumble into a hall of mirrors where every argument has a counter-argument, every action has a reaction, no escape route is offered and the only guarantee is that Afghan civilians will lose.

His political career spans Afghanistan’s modern era. He became a US senator in 1973, the year that the country’s last king, Mohammad Zahir Shah, was deposed after a four-decade reign that coincided with one of the most peaceful periods in the country’s history.

Biden remained in the Senate when Ronald Reagan backed the mujahideen against the occupying Soviet Union and George W Bush ousted the Taliban after 9/11. As Barack Obama’s vice-president, Biden believed the conflict had gone on too long but was overruled, even after the killing of Osama bin Laden in neighbouring Pakistan.

Now, as president, Biden has ripped off the bandage, determining that the 20-year war is unwinnable, that counter-terrorism priorities lie elsewhere and that the US does not have a multi-generational obligation for nation-building. Polls show his decision to withdraw US forces by the end of the month has massive support from the public, not least among sceptics of American imperialism.

Even so, Biden, renowned for his empathy, is about to be confronted by images of atrocities and human suffering that are a direct consequence of his actions. It is true that “the buck stops here”. But is also true that there are myriad causes dating back at least half a century that are painfully difficult to disentangle.

Nearly 50 years of at best political chaos and more typically war has led us to this point

Matthew Hoh

Matthew Hoh, who in 2009 resigned in protest from his post in Afghanistan with the state department over the US escalation of the conflict, said: “This war is a living legacy of the cold war. I was born in 1973; that’s the year the king was deposed. You really can’t ever put a start date on history, but I think that start date is a more accurate start date than 9/11.

“Nearly 50 years of at best political chaos and more typically war has led us to this point. The simple explanations certainly fall flat, as well they should. This notion that somehow the reason what we’re seeing in Afghanistan, occurring now with the Taliban at breathtaking speed, is because Joe Biden pulled 2,500 American troops out from a country the size of Texas makes no sense.”

The Taliban has overrun a string of regional capitals in a lightning offensive since Nato troops largely pulled out of the country on the back of Biden’s decision to withdraw. The government army has superior numbers and technology, as well as an air force, yet has lost control of most of the country and appears on the brink of collapse. The Taliban is paying little heed to Washington’s warning that it will be shunned by the international community if it takes Afghanistan by force.

The fighting has fuelled fears of a refugee crisis and a reversal of recent gains in human rights, particularly for women and girls. Recriminations abound in Washington. Biden said this week he did not regret his decision, pointing out that the US had spent more than $1tn in its longest war and lost thousands of troops.

But Mitch McConnell, the Republican minority leader in the Senate, said the exit strategy was sending the US “hurtling toward an even worse sequel to the humiliating fall of Saigon in 1975”, and urged the president to give more support to Afghan forces. “Without it, al-Qaida and the Taliban may celebrate the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks by burning down our embassy in Kabul.”

The sentiments were echoed by hawkish Republicans such as Senator Lindsey Graham and Representative Liz Cheney, representing a section of the party that remains loyal to the military interventionism of Bush. None, however, has offered a compelling prescription for how to prevent the conflict dragging on indefinitely.

Hoh, who served as a US Marine Corps captain in Iraq and is now a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy thinktank, said: “The US is an empire, a thing that seems blasphemous to say, but what do you call a nation that has between 800 and 1,000 foreign military bases? The empire never wants to lose.

“There are a lot of people in Washington who view the world as if it’s a game of Risk. The commentary is what you would expect from people like Mitch McConnell, Liz Cheney, who the war has never touched personally, except for campaign contributions and donations.”

The Republican critique is also undercut because its dominant pro-Trump faction has little appetite for foreign adventurism. Having long promised to to end America’s forever wars, the then president struck a deal with the Taliban for US troops to withdraw by May in return for stopping attacks on American forces and entering peace talks with the Afghan government. This artificial deadline, with the looming threat of attacks resuming, added to Biden’s complex calculation.

Anthony Cordesman, a strategic analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies thinktank, who has served as a consultant on Afghanistan to the Pentagon and state department, said: “The moment that you announced a withdrawal deadline without tying it to a specific peace proposal – and indeed it may have been that if you announced a withdrawal deadline at all – you created a situation where there was a serious risk that an already weak and divided Afghan government and force would not survive the outcome.”

Although Trump and his allies are unlikely to let hypocrisy stop them pinning the Afghan debacle on Biden, a cynic might conclude that he has little to fear because most Americans either support his rationale or simply do not care. He is more likely to be judged at the ballot box by his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, the economy or healthcare than a war whose moral purpose has long since become shrouded in fog.

William Wechsler, an analyst at the Atlantic Council thinktank, said: “The majority of Americans don’t own a passport, which I remind my friends in Europe all the time.

“When you poll them and say, what are the most important issues in front of America, foreign policy issues usually are pretty low on the list. The average person in Yorkshire was really proud of the British empire, from everything that I’ve read. It’s just a very different psychology here.”

Momentum for leaving Afghanistan has been growing for years so the political blowback is likely to be modest, according to Wechsler, a former counter-terrorism official in the Obama administration. “It’s not like Trump and Biden were bucking a strong domestic political trend. They were following a trend that’s been building for a long time.

“Now, will Biden be criticised for this? Absolutely. Will there be some Americans that will feel very strongly about it? Of course. Will the Republicans, especially if they can get control of various houses of Congress after the midterms, do the kinds of investigations that will make everyone miserable in the administration? I would think that there’s a good chance of that.”

But the most politically problematic scenarios would be a replay of the chaotic retreat from Saigon in 1975 or the deadly terrorist attack on the US consulate in Libya in 2012. “I suspect that the folks in the Biden administration are laser-focused on avoiding those outcomes,” Wechsler said. “You’ve already seen it with the decisions to move forces to to secure the airport and ordering people to be gone.”

Biden came into office with more foreign policy experience than any other US president, focused on the threat of an ascendant China. He was dealt a bad hand in Afghanistan and resolved to play it decisively. As with Obama’s agonising over the humanitarian catastrophe in Syria, his defenders will frame it as the least worst choice in an impossible situation. Afghans, enduring another tragedy, may disagree.

David Rothkopf, an author and commentator on international relations, tweeted on Friday: “US policy in Afghanistan has been 20 years of bad decisions and bad execution in the face of an insoluble challenge. But sure, it’s on Biden.”

The war in Afghanistan will rank alongside Vietnam as one of America’s great modern failures of strategy and execution, Rothkopf added. “The bulk of the responsibility for that failure lies with past administrations and with the leadership in Kabul (and to some extent with Taliban enablers beyond the country’s borders). Biden is doing what is right and what must be done. It is time to turn the page.”