Biden’s old Senate colleagues don’t recognize his current economics. They’re cool with that.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Moderate Democrats who worked alongside Joe Biden for decades say the new president’s economic policies don’t square with the Senator Biden they knew. But they don’t blame him for the change, either.

In the 1980s, Biden voted for the Reagan tax cuts, significantly reducing the tax rate for high-income earners. In the 1990s, he promoted legislation that would have dramatically restricted deficit spending and backed Clinton-era welfare reform ultimately seen as harmful to working class Black and brown Americans. And as vice president, he negotiated major deals with Republicans that included the extension of the Bush-era tax cuts and domestic spending reductions.

But that was the old Joe. The new Joe Biden is pushing historic spending packages as president that could — if passed — usher in the biggest expansion of the social safety net in 80-odd years.

“Joe Biden was a moderate all of his time in the Senate, fiscally responsible,” said former Sen. Kent Conrad (D-N.D.), who served alongside Biden in the Senate for more than two decades. “And now you see he's promoting these very large expenditure plans.”

A Democratic senator from Delaware in the Reagan years and a Democratic president in 2021 aren’t operating in the same environment. And the evolution of Bidenomics over the past few decades reflects just that — mirroring the movement his party has taken and illuminating the massive crises he inherited upon becoming president.

Though Biden’s aides and allies steadfastly maintain that his economic principles haven’t changed, Stefanie Feldman, deputy assistant to the president and senior adviser to the Domestic Policy Council, said Biden’s current economic approach is in part the result of his new status.

“Being a senator and president is quite different, and the president has an ability to persuade in ways and on a scale a senator just does not in order to shape the narrative of the country,” Feldman said in an interview. “I'm not saying he hasn't changed at all. I think his principles are remarkably the same and he applies new circumstances or new facts to those principles, and that leads to new policies.”

Current and former Democratic lawmakers who’ve known Biden through the years describe his current spending initiatives as an evolution. But none see his presidential agenda — cast in the face of the historic pandemic — as a misstep or simply the result of liberal pressure. Conrad, a self-described conservative Democrat, said Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan was “not out of the Biden playbook of the past.” But he said that he’d support it if he were still in the Senate today.

Former Sen. Ben Nelson (D-Neb.) said Biden’s infrastructure plans may be “a bigger bite than I want to swallow.” But he conceded that Biden is remaining "current with circumstances as they change."

Biden’s adaptation is owed in part to the fact that economic policy was not his defining policy pursuit in the Senate. His tenure was marked predominantly by his committee assignments, in particular his prominent perches atop the Judiciary and Foreign Relations Committees.

Those close to Biden define “Bidenomics” as a laser-like focus on the needs of workers, based on the idea that a fairer tax system and strong unions will bolster the working and middle class and close the income inequality gap. To prove the consistency to these core values, the White House pointed to different votes Biden cast over his decades-long career in support of unions, bargaining rights, increased pay and expansions of child and caregiver tax credits.

They say that those principles are what is guiding him now as he attempts to pass more lasting changes to job and social safety programs — from parental leave to child care — with proposals totaling more than $4 trillion.

Republicans argue that Biden’s gone rogue; that the man who sold himself as a moderate to voters has turned the keys over to the liberals in his party. Last month, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell accused BIden of a “bait and switch” — a sign of the 2022 attack ads to come. Senior White House officials and people close to Biden reject the premise that he was a die-hard economic moderate to begin with.

When Biden proposed a federal spending freeze — including Social Security — in 1984, decrying ballooning budget deficits, “that was forty years ago, that was a different time,” said former Sen. Ted Kaufman (D-Del.), Biden’s longtime Senate chief of staff who ran the president’s transition. “And right now, to highlight the differences: We are faced with something we have not confronted since the Great Depression — the country has evolved.”

“It's a changed environment. There's no doubt he's going to deal with it differently than if this was not this situation,” Kaufman added.

The record

To understand Bidenomics it’s important to understand Biden’s political journey. As a young senator in the 1980s, he watched Democrats lick their wounds from electoral defeats in which they'd been cast as poor stewards of taxpayer dollars. A 1980 Wilmington Morning News clipping headlined “GOP victories take liberal pressure off Biden” said the Delaware senator “might come out looking like a conservative” from his stint on the Senate Budget Committee at the time.

One source close to the White House noted that Biden was far from the only Democrat to adopt the Reagan mantra that big government was bad. It was a philosophy embraced by a significant section of the party and the country. Biden, following the will of middle class voters, matched the time, the person said.

By the 1990s, top Democrats largely concluded that the way back to power meant embracing the notion that government wasn't the answer. President Bill Clinton personified a new breed of centrist-minded party leaders and Biden echoed his platform. He warned against indefinitely sustaining deficits in the '90s, arguing they were “dangerously limiting future options for our children's generation.”

“Under current budget conditions, trying to spend our way out of recessions is no longer an option; deficits are now the norm, not a conscious policy choice,” Biden wrote in a 1995 op-ed.

In 1997, Biden and 10 other Democrats voted in favor of a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution requiring a three-fifths majority to enact deficit spending to the floor, but it narrowly failed. It was the third time he’d voted for such a bill since 1995.

White House officials who spoke to POLITICO noted that during that same balanced budget debate, Biden also supported a failed provision that would have paused the rule in the event of a recession. That nuance — making deficit spending temporarily acceptable —showed that Biden’s values have been consistent, they argued.

“A balanced budget amendment at that time is a totally different proposal,” said Kaufman. “Clearly no one's offering a balanced budget amendment” now.

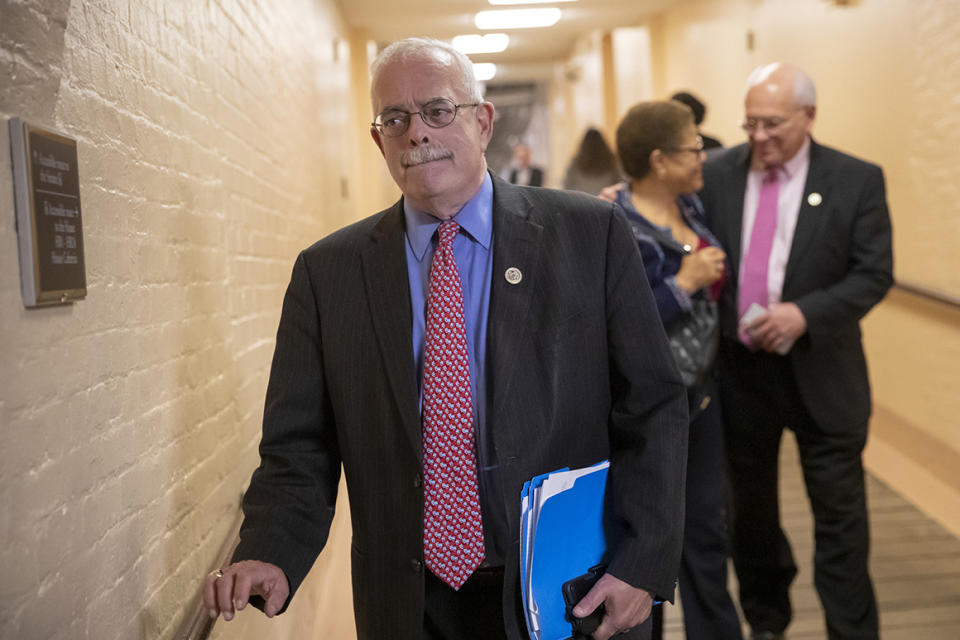

Others who worked with and know Biden said that much of the time, his policies have reflected the moment. Rep. Gerry Connolly (D-Va.), a former Biden staffer in the 1980s, said that during his early Senate career, Biden was “always a little on his guard about his liberal instincts, because he was fearful it was too far out front of where the country was.” Still, Connolly praised Biden's actions, saying the “mark of a good political figure is the ability to evolve with new experience.”

Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-N.J.), who first met Biden decades ago, said the president is “obviously supporting things and saying things now that I can't see coming out of his mouth 40 years ago” but he can’t be defined by any “glib words” like “conservative or liberal or moderate.”

Changing circumstances

Biden took over the presidency at a historically perilous time. And former Senate colleagues say his economic plans — which combined with the Covid-relief law add up to more than $6 trillion — are meant to address those perils. It’s not just the pandemic, though. Income inequality, the rise of China and the dangers of climate change are all at the forefront of his agenda; convincing him and his team that they need to move quickly.

Left unaddressed, “this separation, this feeling of alienation will only grow among people who have real serious financial challenges,” said Conrad.

Nebraska Democrat Bob Kerrey likewise argued that Biden’s economic agenda is a clear attempt to address the growing polarization across the country that’s fed conspiracy theories and a belief among some voters that the government and mainstream culture are excluding them. If successfully passed, Biden’s jobs and family proposals could convince working class voters that government involvement is good for them and essential to a democracy under strain, the former senators argued.

“We have to think about these proposals inside the context of being able to persuade the rest of the world, that democracy can make these kinds of allocations into high wage manufacturing,” said Kerrey. “That you don't need a top-down, single party system that the Chinese have.”

Biden himself has presented his infrastructure plan in these terms. He’s spoken of the need to reestablish the country’s manufacturing prowess through renewable energy job creation. And he’s tried to convince fossil fuel workers that there is a place for them in an economic agenda that is consciously trying to tackle climate change and confront China.

As Brian Deese, head of Biden’s National Economic Council, put it in an interview with the New York Times: “there is a big question about, can the United States deliver for its own citizens? Can the United States competently govern and invest in things that are obviously beneficial to its own welfare, its economic strength, its economic resilience?”

Same principles, new moment

Biden’s policy advisers say his current spending proposals contain obvious similarities to approaches he took in the past. The senator who championed a “pay-as-you-go” budget during his prior presidential runs, has stressed that his jobs and families plan must be paid for.

The question is, will Biden stick to it. It’s far from certain that Biden’s preferred tax increases on corporations, capital gains and households earning more than $400,000 a year will ultimately pass Congress. More recently, the White House has said deficit financing for these items is not off limits.

Jared Bernstein, a member of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, said Biden has always promoted “a balanced approach to fiscal rectitude,” which means that “when you're in a downturn, temporary measures can be deficit finance.” But, Bernstein added, Biden “believes that longer term programs, more permanent programs, should have pay-fors.”

“Here we have a set of policies that both enhance the fairness in the tax code, push back on after-tax inequality and provide a set of opportunities and good union jobs to the middle class,” Bernstein continued. “And that defines Bidenomics for as long as I've known him, which has been a pretty long time.”

When Bernstein first sat down with Biden in an extended fashion it was in 2008 in the soon-to-be vice president’s Delaware home.

I“He pulled out from a folder a graph that I had made with my colleague, Larry Mishel, that showed how, while the economy had been growing for 30 years, the middle class had been left behind and he pointed at that gap,” Bernstein said. “He said, 'If you come to work for me, our job is going to be to try to close that gap.'”

Bernstein said he sees an “economic moment catching up to a policy agenda that this president has always stood for.”

Mishel, in a separate interview, saw a different timeline. The “economic policy agenda on the center left has shifted and [Biden] along with it,” he said.

But Mishel added that while Biden’s history is marked with moderate “New Democrat” fiscal philosophies, he’s also long been a “labor Democrat.”

Another longtime Biden confidante summed up Biden’s calculus another way.

“You can look at the votes and say, ‘Well, that's center-right, that's center-left,” said former Sen. Chris Dodd, who helped with the president’s transition. “[But] Joe's North star has always been the middle-class and like any other constituency, the middle-class' views on things have changed from time to time.”

At times that constituency wants “fiscal austerity” and other times they don’t, said Dodd. “It's an audience that is not on some clear straight trajectory ideologically.”