Biden’s Speech Told Us a Lot About How He Sees America’s Role In the World

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

President Joe Biden’s emergency budget request—which totals $105.85 billion—is not only a plea for much more military aid to Ukraine, Israel, and (to some extent) Taiwan. It’s also a political document designed to attract those lawmakers and their constituents who are leery of spending money on faraway conflicts.

The request includes $61.4 billion for Ukraine, $14.3 billion for Israel, $2 billion for security assistance to Indo-Pacific allies (mainly Taiwan), and $9.15 billion for humanitarian supplies to Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, “and other needs” (though officials did not specify which recipient gets how much).

However, it also includes $13.6 billion for security on the United States’ Southern border—thus, Biden seems to hope, mollifying critics who say he should focus more on our own borders than on the borders of faraway foreign allies.

This sum—only slightly less than the amount requested for Israel—includes money for 1,300 new Border Patrol agents (in addition to the existing 20,000), 375 immigration judges, 1,600 asylum officers, and 1,000 Custom and Border Protection officers tasked with seizing shipments of fentanyl. None of this has much to do with America’s moral geopolitical stakes in Europe, Asia, or the Middle East.

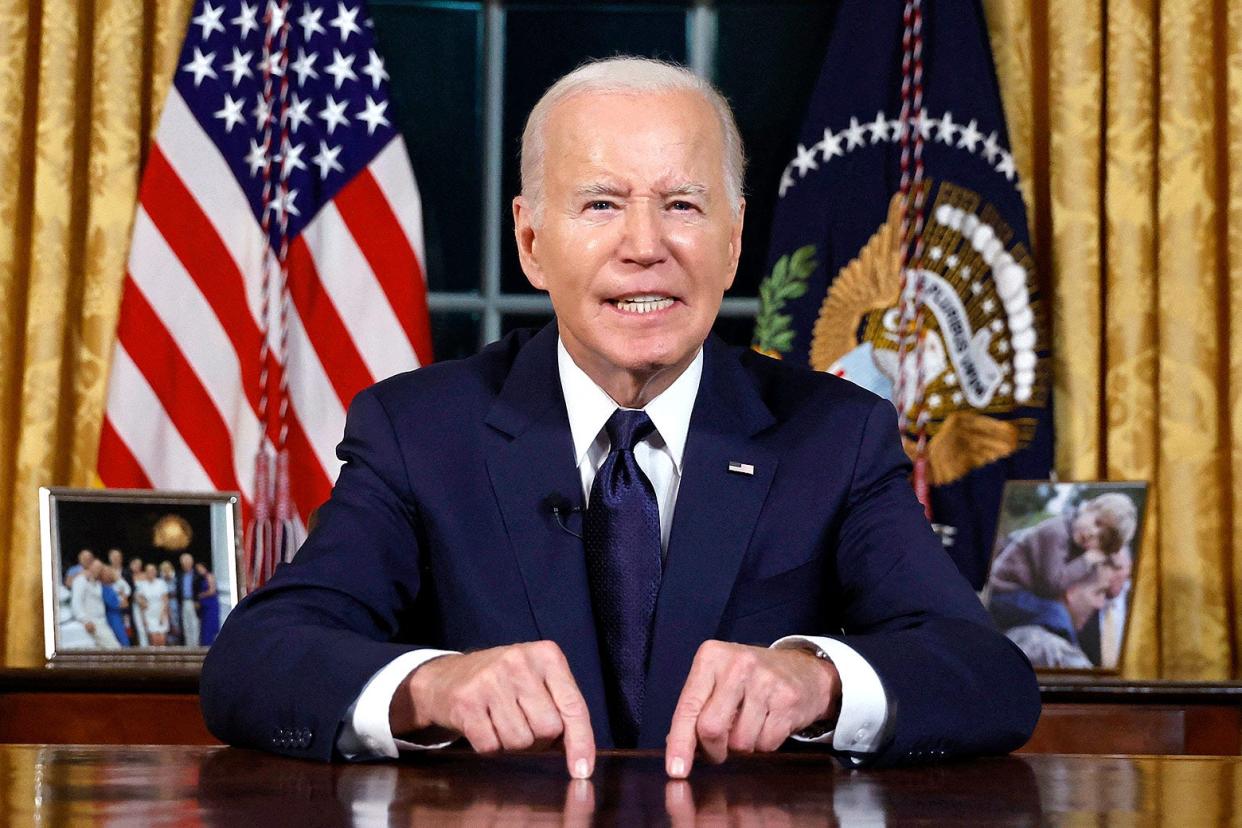

As a further enticement to America First-ers, the budget document—which the White House released Friday morning—notes that most of the weapons sent to Ukraine and Israel come out of U.S. military stockpiles. Therefore, most of the newly requested money—$50 billion, to be precise—will be spent on replenishing those stocks. In other words, it will go to U.S. defense contractors. Biden stressed this fact in his televised speech Thursday night, noting that Patriot air-defense missiles are made in Arizona and that artillery shells are manufactured in 12 states across the country, including Pennsylvania—both of them swing states in the upcoming election. His national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, made the same point at a press conference Friday morning, saying it will create jobs.

But most of Biden’s 15-minute speech was devoted to loftier views, which he has held throughout his 50 years in national politics—the importance of allies, the moral value of protecting democracies from aggression, and America’s role as “a beacon to the world, still.”

When terrorists and dictators don’t pay a price for their aggression, Biden said, “they keep going.” If Vladimir Putin succeeds in conquering Ukraine, he could move on to Poland and the Baltics. Those are NATO members, meaning if they’re attacked, the U.S. would be treaty-bound to respond directly. “We do not seek to have American troops fighting against Russia,” Biden said. So we need to continue helping Ukraine stave off Russia now—not with troops, but with weapons and other forms of assistance.

“If we walk away and let Putin erase Ukraine’s independence, would-be aggressors around the world would be emboldened to try the same,” Biden said. “The risk of conflict and chaos could spread in other parts of the world—in the Indo-Pacific, in the Middle East: especially in the Middle East.”

Biden and others have argued this case many times before, but in Thursday’s prime-time speech, he made a new point—linking Hamas’ attack on Israel with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, saying that they are essentially two aspects of the same conflict.

“Hamas and Putin represent different threats,” Biden said, “but they share this in common: They both want to completely annihilate a neighboring democracy.” He also noted that Iran is helping both Hamas in Gaza and Russia in Ukraine—and that North Korea is providing weapons to Russia as well.

Though he did not utter the words “axis of evil” (the phrase that President George W. Bush coined in 2002 to describe what he saw as a growing alliance among Iraq, Iran, and North Korea), Biden seemed to be suggesting that the concept now applied to Iran, North Korea, and Russia.

There is something to this—the three countries cooperate with one another on certain matters and share some of the same foes—but it would be unwise to push the conceit too far. The world is dangerous enough, and tensions with Iran and North Korea are strained enough, without conflating them into one gigantic powder keg—or viewing a conflict with any one of them as an inevitable prelude to World War III.

It may be significant that Biden didn’t mention the word China even once in this speech, even though its president, Xi Jinping, has an alliance with Putin and is trying to make inroads in the Middle East as well. Xi also poses a threat to Taiwan—that threat is the main reason for the extra $2 billion that Biden is requesting for Indo-Pacific security. Biden may have a one-on-one meeting with Xi at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco next month. He may not want to alienate Xi before that session—and may see opportunities for the two countries to cooperate in damping down global tensions.

Meanwhile, Biden will face challenges in pushing his security package through Congress. The Senate may pass it quickly, but the House can’t take up any legislation until the speaker’s seat is filled, and that may take a while. Also, many Republicans and some Democrats are keen to wind down, rather than double down on, the commitment to Ukraine. And while recent polls show a strong majority of American citizens support Israel, not quite half of them favor sending them more arms, and many more fear the possibility of getting sucked into a wider war. More of those surveyed prefer a cease-fire and attempts to craft a diplomatic solution—though not even seasoned experts have any good ideas on how to do that.

Israel is still intent on wiping out Hamas, or at least destroying its ability to rule Gaza or threaten Israel, and is poised to invade Gaza in order to do so. In his recent trip to Jerusalem and in his speech Thursday night, Biden urged the Israeli government not to let their rage—an understandable reaction to Hamas’ murderous attack on civilians earlier this month—undermine their reason; to uphold the law of war (meaning to minimize civilian casualties); and to keep in mind that Hamas does not reflect the views or interests of all Palestinians.

“As hard as it is,” Biden said Thursday, “we cannot give up on peace, we cannot give up on a two-state solution” to the long-standing Israel-Palestinian conflict—though many in the Middle East have long ago, in many cases reluctantly, done just that.

In an interview this week in the Free Press, Michael Walzer, author of the classic 1977 book Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument With Historical Illustrations, said of the current conflict:

The situation is so awful, but I still would hope for an Israeli response which is in accordance with the laws of war—a war fought that way would at least maintain the possibility of some progress afterwards, of some better aftermath. But this is a terrible time, and I’ve never found it so difficult to think about what ought to be done… It’s a situation where every decision is agonizing.