Biden’s A team: key figures pushing the president’s agenda in his first 100 days

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Related: Biden’s 100 days: bold action and broad vision amid grief and turmoil

Joe Biden’s first 100 days in office consisted largely of his administration’s rush to reverse Donald Trump’s approach to the coronavirus pandemic. Much of the national spotlight has fallen on how the new US president has addressed the crisis or which aides have been closely involved in coordinating the federal government’s responses.

But the Biden administration has also had to grapple with immigration policy, a huge infrastructure bill and staging a global climate summit, as well as the fallout from the murder trial of former policeman Derek Chauvin – amid all the other up and downs of daily news cycles.

All of that has pushed Vice-President Kamala Harris and other key aides into the center of the public sphere.

Below are seven key members of the administration who have had an impact on the 46th American president’s first 100 days in office:

Kamala Harris, vice-president

For much of Biden’s tenure, Vice-President Kamala Harris has been closely at the president’s side.

Harris, the first female vice-president and first of African American and Asian heritage, is a regular presence at major bill signings and aides say she is oftentimes in the room or close to the president during big decisions. Given her likely top spot in the jostling to be Biden’s successor, that is not really a surprise.

During the earliest days of Biden’s presidency, Harris’s portfolio wasn’t entirely clear. She was often the highest-level contact between world leaders and the administration. She has also served as a top surrogate for the Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan and its vaccination efforts.

At times, Harris’s at-large portfolio received blowback from Democrats. More recently, Biden assigned Harris to focus on the consequences of an influx of migrants at the southern border. That too has spurred some confusion about her role as aides maintain her job is not to lead the administration on stemming the flow of migrants coming to the US.

Ron Klain, Biden’s chief of staff

Ron Klain has been one of the more public-facing chiefs of staff in recent memory. He is a mainstay interviewee on cable news networks. He can be classified as very online by political junkies and rabid Twitter users. He has also served as one of the administration’s highest-ranking conduits between the White House and the progressive wing of the Democratic party.

Klain has helped shape the administration’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, drawing on his experience as the Ebola response coordinator during the Obama administration, as well as selling Biden’s infrastructure plan to different blocs in Congress.

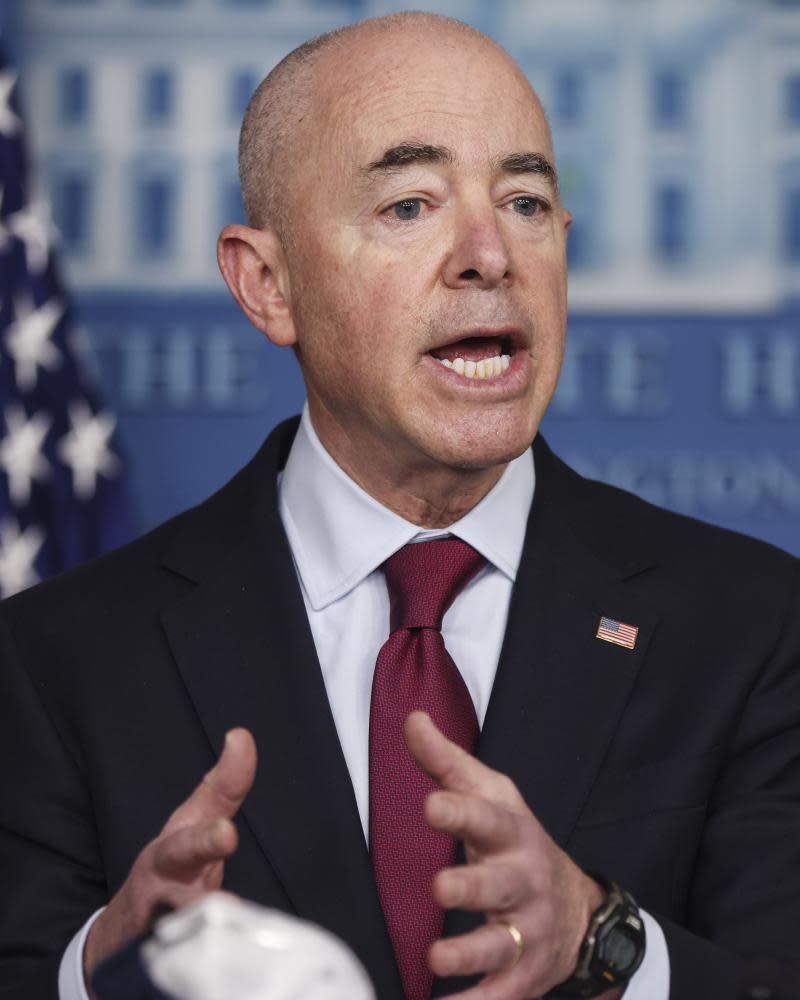

Alejandro Mayorkas, Department of Homeland Security

Alejandro Mayorkas is the first immigrant and Hispanic American to run the Department of Homeland Security. His charge includes not just immigration and border security but also fighting terrorism.

Mayorkas has vowed to improve his department and the federal government’s defenses against hacking. He has warned that domestic extremism “is the single greatest terrorism-related threat” the country faces.

Part of Mayorkas’s job has been to defend the Biden administration from critics who argue the president’s approach on the southern border has been inconsistent. Mayorkas fired almost all of the members of the homeland security advisory council.

Brian Deese, national economic council

From helping craft and coordinate the Biden team’s Covid economic relief and job creation policies to briefing the president and vice-president directly, to selling major legislation to members of Congress, Brian Deese is always involved.

Deese leads the White House’s national economic council and is a federal government veteran.

In the Obama administration he served as a senior adviser to the president and was the deputy director and director of the Office of Management and Budget. Deese was also involved in negotiating the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

Out of government, Deese was involved in sustainable investing at BlackRock. That expertise in environmental issues positions Deese to play a leading role in future green energy proposals the Biden administration will push.

Deb Haaland, Department of the Interior

After her historic visit to Bears Ears national monument, Haaland vowed to help protect the site, which is sacred to Native Americans, “for generations to come”. Just over three years ago, the Trump administration downsized the federally protected area by 85% – the latest protected area reduction in US history – and opened up the site to cattle ranching and oil drilling.

The first Native American in US history to lead a cabinet department, Haaland will be at the helm of the agency that oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

She has inherited a fractured interior department – one that her predecessor, ex-oil and big ag lobbyist David Bernhardt, tried to dismantle from the inside. So in the month since her confirmation, she has acted swiftly to try to undo the damage.

Haaland issued a secretarial order prioritizing environmental justice and revoked a number of Trump-era policies that promoted oil and coal extraction. She created a new unit to investigate cases of missing indigenous women, and established a climate taskforce.

Addressing the United Nations Forum on Indigenous Issues last week, she acknowledged a “difficult moment has been thrust upon us”. But, she added, “it’s an opportunity to usher in a new era.”

Pete Buttigieg, Department of Transportation

Buttigieg’s appointment as transportation secretary initially raised some eyebrows. The former presidential candidate had limited experience managing infrastructure – as the mayor of a city with about the same population as the number of people who move through DC’s Union Station each day.

But backed by a deputy secretary and a slate of other staff with significant transport experience, and led by a president who loves trains so much it became his nickname, Buttigieg is off to a running start implementing major infrastructure reforms. Like pretty much every other high-level Biden appointee, he began by reversing Trump-era rollbacks on regulations for tailpipe emissions and other environmental standards.

Buttigieg has proposed a $1bn grant program for cities seeking to improve transportation infrastructure and indicated that the department would prioritize projects that consider racial equity and environmental sustainability. Cities are already scrambling for the grants. Los Angeles, for example, is seeking $45m to revamp major roads in South LA – where mostly Black and Latino residents must cope daily with traffic-choked interstate highways and the smog that emanates from it.

Buttigieg may not have been the first pick of environmental advocates, but he is someone they have been able to rally behind, and strategically pressure to address longstanding environmental justice crises.

Rochelle Walensky, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

When Walensky took the reins at the CDC, she promised to “restore public trust in the CDC” – after politics encroached and upended the agency’s ability to govern through the coronavirus pandemic.

Behind the scenes, she has charged a deputy with reviewing all Covid-19 guidance to ensure it is in line with the latest evidence. In front of TV cameras, she has begged local leaders to stay the course and not lift restrictions too soon – and shed public tears as she admitted, amid the late-March uptick in coronavirus infections, despite all the hope that vaccines offer, “right now, I’m scared.”

Walensky has not fully managed to restore trust over the past few months. She has been unable to convince Republican governors to refrain from lifting mask mandates and throwing Covid-era cautions to the wind.

The agency’s advice to pause administration of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine has drawn criticism and concern from local officials who worry the decision could heighten vaccine hesitancy. But as Walensky said during her emotional White House coronavirus briefing last month, “I made a promise to you – I would tell you the truth, even if it was not the news we wanted to hear.”