Biden's vaccine order not unprecedented: George Washington required smallpox inoculations

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If President Joe Biden ordering U.S. military service members be vaccinated against COVID-19 sounds un-American, it's not without precedent.

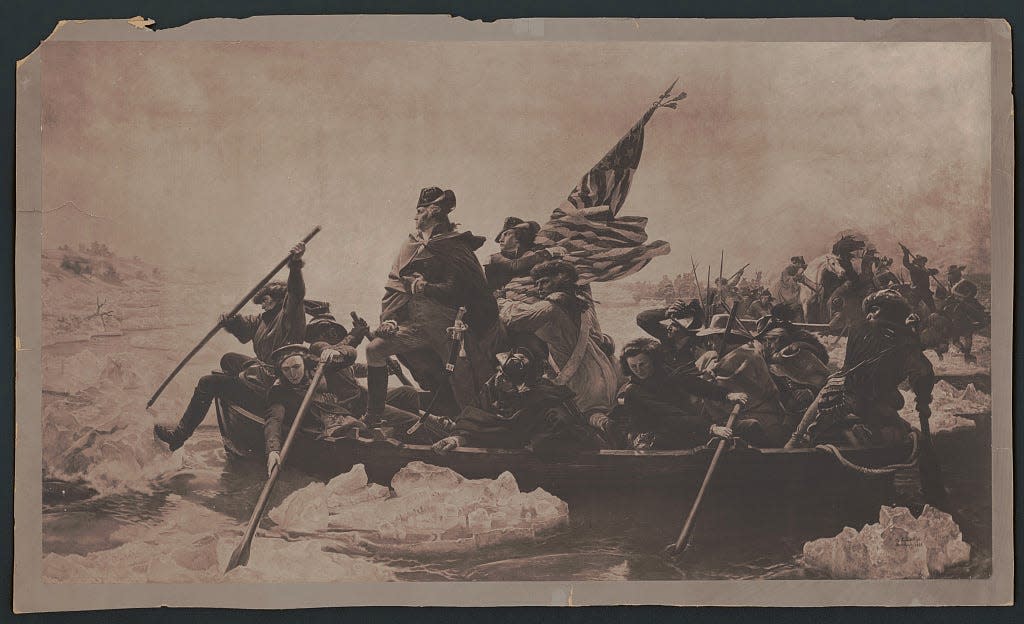

Gen. George Washington — later the first president of the United States — did pretty much the same thing during the Revolutionary War on Jan. 6, 1777. Smallpox was raging across North America and threatened the effort for independence from Great Britain.

Washington himself, about to turn 45, had been inoculated against the virus by contracting it while in Barbados when he was 19. His face bore the scars from that illness, said David Head, a University of Central Florida early American history lecturer and author.

Editorial: Who we lost in 2021 and what we can take from their lives into 2022

“Smallpox is one of those devastating 18th century diseases. Really it goes back into antiquity," Head said in an interview. "It’s been eradicated today, but it’s one of those things we used to have to deal with. It was highly contagious, with debilitating pustules on the sufferer’s body."

Its symptoms also included fevers, headaches, body aches and severe fatigue, and it could be deadly.

In a much-cited 2004 article for The Journal of Military History, Ann Becker, associate professor at SUNY Empire State College, quotes the British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay: "That disease … was then the most terrible of all the ministers of death. The havoc of the Plague had been far more rapid, but the Plague had visited … once or twice and smallpox was always present, … tormenting with constant fears all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power."

UCF's Head said there was a controversial technique of inoculation available at the onset of the Revolutionary War.

A surgeon or doctor would scrape a pustule off a sick person and smear the pus into a small cut in a patient's arm.

“It’s totally gross to think about that," Head said. "It’s a live virus, so the person is going to get sick.”

At the time, soldiers were unaware of germs and how smallpox spread. Many people in the 18th century still believed in “mysterious, ancient ideas about humors,” a system of thinking about medicine dating to at least ancient Greece and rooted in the belief that pain and illness were caused by an imbalance in the four bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile, Head said.

“They don’t know how this disease really spread, but they can see the effects everywhere.”

Inoculations through the skin, rather than through droplets from sneezing, typically caused a weaker virus. Still, it was chancy.

“It’s possible you get sick and die from inoculation. It was much more risky than anything we’re used to seeing,” Head said.

Washington's changed thinking

At the start of the war in 1775, Washington forbade soldiers from being inoculated.

Those who did faced punishment, including being kicked out of the army and having their “names published as a traitor," Head said.

Washington's opposition centered around the recovery and quarantine period — a month — which took much-needed troops out of action for a time. That produced a risk the Americans' revolution could have been put down.

But as the war carried on into 1776, disease emerged as the greater danger, accounting for 90% of the Continental Army's deaths. Smallpox was the leading scourge.

Making things worse, the Brits were largely immune from smallpox, giving them a decided advantage.

Winter: Time to act

Maurizio Valsania, professor of American history at the University of Turin in Italy, who's working on a biography of Washington, described Washington's decision-making process in an email to The News-Journal.

"At first, Washington himself was iffy about the procedure; he feared that his troops would be incapacitated for too long, and that the British would take advantage of the situation," Valsania wrote. "He later realized that mass inoculation was the only sensible solution."

So on Jan. 6, 1777, Washington ordered inoculations for all forces who were traveling through Philadelphia. He ordered it be kept a secret from the British.

In a letter to Dr. William Shippen Jr., Washington wrote: "Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army … we should have more to dread from it, than from the Sword of the Enemy."

Washington took a risk that the British would hold off on new attacks for a few weeks.

“Winter is traditionally the time when not much fighting occurs. The weapons, the muskets, don’t work as well in the wet rain and snow, so the fighters usually take a breather in the winter quarter," Head said.

In reaction to Washington's order, some American generals and officers were hesitant, Valsania wrote.

"There was some kind of pushback but also there was the fact that troops practiced the procedure by themselves, without medical supervision," he wrote. "All in all, inoculation helped the recruitment."

"With the threat of smallpox diminished, the Continental Army saw a surge of new recruits in 1777," he added, citing a deeply researched article on the National Parks Service website.

Importance in winning Revolutionary War?

While they appear to be in agreement that Washington's inoculation mandate was important to the independence cause, historians take differing views on just how critical it was.

Valsania called Washington's decision "pivotal to secure military success," while Head contends it was among several key factors that led to victory.

“It certainly helped to have more men be a greater, effective fighting force," Head said. "It certainly was possible they could have inoculated all the troops and still lost. … It was very helpful and without it, I don’t know whether they could have won the war. It makes it much more difficult if the smallpox continued to rage through the army, would have made it much harder, much harder to win without it.”

Roger Smith, a St. Augustine historian, author and Flagler College adjunct professor, called the inoculations “the single most important thing” Washington did to win the war.

Not only did it protect the Continental Army for six years, the remainder of the war, but it played a role in a turning point the following year.

Smith cited “Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82,” a 2001 book by Elizabeth Fenn, as “the bible” on the period. In 1778, the British Army was considering a “Pearl Harbor-type attack on New Orleans from Pensacola,” Smith said.

“It didn’t happen because when they marched 1,000 troops into Pensacola to launch this invasion, it got called off. Five hundred of the troops were Brits and 500 were (King George) loyalists out of Maryland.”

A good number of the Maryland Loyalists Battalion contracted smallpox and about half of them died, Smith said.

That failure kept intact the Spaniards who controlled the Louisiana Territory and allied with the American revolutionaries.

Washington's decision to inoculate his troops spotlighted his strength as a leader, Head said.

“This is where I think Washington is most impressive. This ability to make these decisions. Imagine the burden of command, having to make decisions constantly with imperfect information.

"What Washington does here is he balances the pros and cons very well," Head said. "He understands the tradeoffs."

In his letter informing Congress of his decision to inoculate, Washington writes he made it “after mature deliberation.”

He underscored that phrase, mature deliberation, concluding: “I think that really characterizes Washington’s style."

Never miss a story: Subscribe to The Daytona Beach News-Journal using the link at the top of the page.

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: Military vaccine orders: George Washington also had troops get inoculated