Dems are going after Big Tech. It’ll affect almost everything you do online.

House Democrats' proposed antitrust overhaul pitches itself as a fight for a fairer internet, less riven by special dealing and conflicts of interest — through provisions aimed surgically at the practices of just a handful of the largest U.S. companies.

The proposal for the biggest change to U.S. antitrust law in decades would almost exclusively target Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and potentially Microsoft, even without mentioning any of those companies by name. The narrow focus could make the House bill more palatable to Republicans than a more sweeping Senate proposal for cracking down on monopolies — while heightening the stakes for the tech giants that would find themselves singled out.

The results could bring big changes to some of the industry’s best-known products, from Amazon Prime and Google’s search results to Apple’s App Store and Facebook’s Messenger and Instagram. LinkedIn and Microsoft Office could even feel the bite.

The bills aim to eliminate the “self-preferencing” the tech giants engage in by promoting their related products and reducing the discoverability of rivals, said Sally Hubbard of anti-monopoly group Open Markets Institute. And if the problems can’t be resolved by non-discrimination rules or opening up the platforms, the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission can sue to break them up, she said.

“Policing discrimination can be like a game of Whac-A-Mole because there are so many levers these platforms can push,” said Hubbard, a former enforcer who now serves as director of enforcement strategy at the anti-monopoly advocacy group Open Markets. And she said if the proposals for tougher enforcement don’t work, you can “structurally remove those conflicts of interest as we’ve done in other industries.”

The five-bill package that House lawmakers announced Friday would let the Justice Department and the FTC designate “covered online platforms” for enhanced enforcement, but only if the companies meet certain thresholds: The business’ parent company must have a market value of at least $600 billion, a mark only 10 corporations worldwide exceed. And the company has to serve at least 50 million U.S. users or 100,000 U.S. businesses each month.

The second threshold would let other, undoubtedly mammoth companies off the hook, including Saudi Aramco, Tesla and Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

For the big tech titans, meanwhile, a range of new restrictions would kick in: They could no longer buy up potential rivals, as Google did this year by purchasing Fitbit, or discriminate against competitors who use their platforms, as critics have accused Apple and Amazon of doing. They would also need to make it easier for users or businesses to transfer their data to other platforms. And the DOJ and FTC would have the option to sue to break up the giants.

Here’s a look at how the bills could affect each of the huge tech companies:

Facebook’s greatest impact would probably come from bills that focus on non-discrimination (H.R. 3816 (117)) and so-called interoperability (H.R. 3849 (117)), the seamless transfer of users’ data between two platforms.

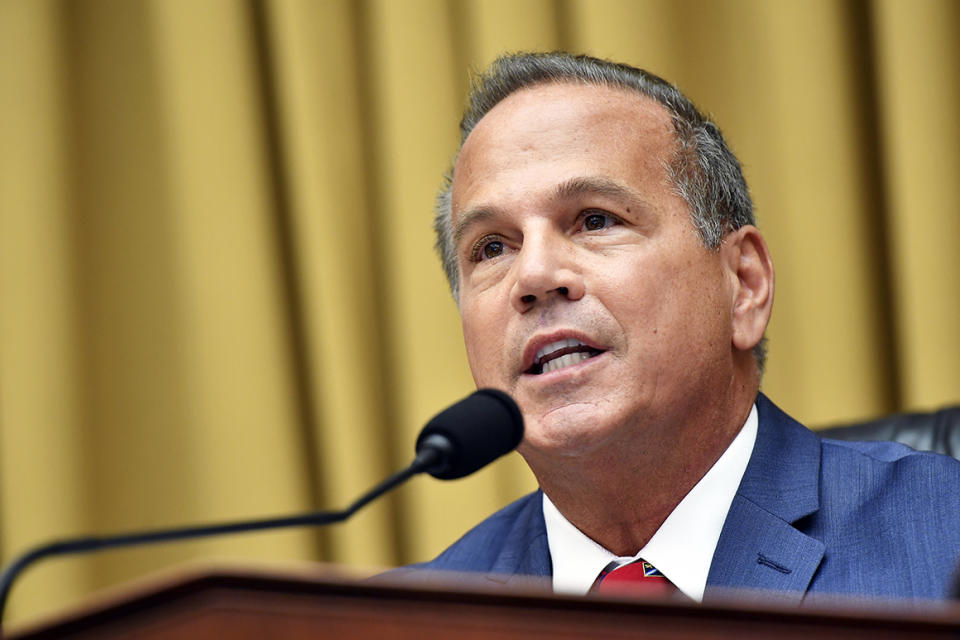

The non-discrimination bill, by House Judiciary antitrust Chair David Cicilline (D-R.I.), would prohibit a company from giving its own products advantages that it doesn’t make available to others.

For example, Facebook has made it easy to cross-post between its main site and its photo-sharing app Instagram. It has also worked to integrate its messaging services on Instagram, Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp. Under the House proposal, the company would need to offer those same tools to rival businesses, so that users could cross-post videos or text to other social media services, or send messages from Facebook to other chat platforms.

The interoperability bill would also force platforms to build tools that allow users and businesses to easily take their data when they leave. That is aimed at making it easier for users to switch between services if their old platform changes its privacy policy or a new one offers cooler features — potentially making it easier for someone to vie with Facebook and its 2.7 billion user base.

The interoperability bill is key to changing the industry dynamic in which start-ups avoid competing with the tech giants, instead seeking to be bought out by a Google or a Facebook, said Ernesto Falcon, senior legislative counsel at the digital rights nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. That bill, along with a proposed mergers ban (H.R. 3826 (117)) that would forbid the tech giants from buying up possible rivals, will help encourage investment in alternatives, he said.

“It frees up innovators and people trying to make a better product or better service,” said Falcon, who formerly worked as House Democratic staffer focused on internet and telecom policy. If Congress can cut down on buyouts “and promote switching and competition, it should create a very different market than what we have today," he said.

Facebook declined comment on the legislation.

Amazon

That interoperability bill would also apply to business information. That means third-party sellers on Amazon could more easily take their listings and reviews to other marketplaces.

Some of the conditions in the non-discrimination legislation appear aimed directly at the e-commerce giant. Under the bill, for example, a dominant online platform would be forbidden from supporting its own products using non-public data from companies it does business with.

Amazon faced accusations of doing just that a year ago, when The Wall Street Journal reported that its employees had looked at data from the company’s third-party sellers to determine what products to offer in competition with them. Amazon has said it forbids the practice, but co-founder Jeff Bezos admitted to Congress last summer that he couldn’t guarantee nobody had violated that policy.

Amazon is also contesting charges the European Union filed in November alleging the company uses data from third-party sellers to help determine which products it wants to offer.

The non-discrimination bill is a “direct hit” on the tech companies’ dominance because it would prohibit them from using their power to steer users to their other products, said Hal Singer, an antitrust economist at economics consulting firm EconOne.

If the House bill passes, the Amazons of the world “can clone to their heart’s content,” said Singer, an outspoken critic of the company. “They can steal ideas to their heart’s content. What they can’t do is use their platform power to steer users to the clone.”

Perhaps even more important: The bill would forbid a tech giant from conditioning companies’ use or placement on its platform on whether they buy other services. That proviso takes direct aim how Amazon assigns vendors to its coveted “Buy Box,” the default “add to cart” feature that captures as much as 82 percent of sales by some estimates.

Critics argue that Amazon unfairly pushes sellers to use the company’s logistics and delivery operations, including its Prime service, to win the Buy Box — a claim Europe continues to investigate. At last summer’s congressional hearing, Bezos said the marketplace’s algorithm may “indirectly” favor those who pay the company to fulfill orders.

Amazon declined to comment on how it believes the legislation might affect its marketplace or Prime.

Apple

That same provision in the non-discrimination bill could prevent Apple from continuing to require developers in its App Store to use its in-app purchase system, which charges a 30 percent commission on digital goods or services. The store is the only place where iPhone and iPad users can download apps — a fact that helped drive an antitrust trial last month in which the Fortnite-maker Epic Games sued Apple.

The legislation would also prohibit platforms from engaging in two other behaviors that developers have raised in complaints about Apple: restrictions on customer communications and use of customer data.

Apple’s contracts with developers place certain limits on how they use customer data. For example, developers are prohibited from emailing iPhone users unless they separately obtain the users’ email address. They are also forbidden from telling customers that cheaper prices are available elsewhere. Both policies were at issue in the Epic trial.

The Coalition for App Fairness, a group of 55 companies including Spotify, Match and Epic focused on lowering fees and restrictions on app developers, praised the non-discrimination bill in particular as a needed reform for digital marketplaces.

Apple didn't respond to a request for comment on the legislation.

The measure would also prohibit Apple from preventing users from uninstalling its default apps. While the iPhone-maker has more recently made it possible to delete some apps that come pre-installed on the phone, a handful of those defaults, including Messages or Find My iPhone, can’t be removed even if a user downloads an alternative.

The same provision on default apps would apply to mobile devices running Google’s Android.

But the biggest challenge for Google under the legislation is how it would affect the company’s search engine. Right now, Google gives its own services greatest priority at the top of a search results page — the reason Google Maps and reviews appear first on searches for local businesses and YouTube tops those for music or video.

That prominent placement is a “tech convenience” that users like, said Adam Kovacevich of the Chamber of Progress, a tech lobby for companies including Amazon, Facebook and Google. He warned that the bills would prohibit it.

But Charlotte Slaiman, a former FTC lawyer, said Google would be blocked only from automatically giving preference to its own products.

“If Google Maps really is the best, it can be at the top of the page. What we see right now is Google can put its products at the top just because they are its products,” said Slaiman, who is now with Public Knowledge and advised the House Judiciary antitrust panel on the bills. Her organization accepts funding from all five of the big tech companies but says it limits their donations to avoid undue influence.

The bills could also hit Google’s advertising technology business, the key to its fortunes and the reason that the company ranks No. 1 in revenue from the worldwide market for online display ads.

Critics allege that Google’s ad technology platforms — tools used to buy and sell the display ads that help fund many websites — give each other advantages in the online advertising auctions. The bills would prohibit offering a leg up.

Google declined to comment on the bills.

Just last week, Google agreed to pay a €220 million fine and make changes to its ad tech tools in response to a French antitrust investigation that found that the company favored its own online ad services tools. The search giant pledged to make its DoubleClick Ad Exchange — which organizes the auctions that allow publishers to sell their ad space to advertisers — work with other platforms, but that promise doesn’t extend beyond France.

Microsoft

One big question mark is how the bills might affect Microsoft.

Microsoft’s LinkedIn social network has about 175 million U.S. users, probably qualifying it as a covered platform under the legislation. If it falls under the purview of the House legislation, it would have to allow rival companies to operate with the platform and build tools to let users transfer their profiles to other sites.

Its ubiquitous Microsoft Office products, undoubtedly used by more than 100,000 U.S. companies, also seamlessly work with one another. From the Microsoft Outlook email client, for example, users can start a Microsoft Teams video conference with one click. The legislation might require Microsoft to allow that same one-click functionality with other office-productivity tools, like Slack or Zoom.

Microsoft declined to comment on these possibilities.