The biggest thing you’ve never heard of: How EROS changed the world from a cornfield

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center is celebrating its 50th anniversary.

If you’re like most South Dakotans, EROS is the most important building you’ve never heard of. If you know it at all, there’s a strong chance you live in the Sioux Falls area and a slim chance you actually understand what happens there.

That’s in spite of how hard my coworkers and I tried to change that between 2018 and last year, when good fortune and a call from Searchlight Editor Seth Tupper pulled me out of public relations and back into journalism.

That EROS remains mysterious is perhaps a sad commentary on our work, though I think we occasionally did some great stuff.

The sadder thing is this: The EROS you don’t know about represents, unquestionably, South Dakota’s most effectual long-term contribution to the global scientific community, and arguably its most impactful to the world at large. It’s not even close.

Doubt it? You shouldn’t. I’m biased, but I’m not wrong.

It’s no exaggeration to say that anyone with a map on their smartphone has a little piece of EROS in their pocket. To be clear, EROS doesn’t make smartphone apps. Ironically enough, cell phone reception at EROS, which is 18 miles from Sioux Falls and surrounded by cornfields, is atrocious.

My point is this: The technology behind satellite-derived measurements of the Earth’s surface and the means to understand them – the technology that makes it possible for you to go back in time to watch glaciers recede, lakes fill or drain, or track wildfire damage – started with the Landsat satellite program and EROS.

Gambits, greased palms and happy accidents

To defend this bold claim, I need to take you back to 1966. That was three years before the first moon landing, a time when the attention of the public and scientific community was fixed on looking into outer space, not down from it.

That was the year former USGS Director William Pecora convinced Department of Interior Secretary Stewart Udall to announce the agency’s intention to launch a satellite to monitor the Earth’s surface.

They didn’t tell NASA, though. Instead, they issued a press release announcing their plans, which served to force NASA’s hand into a partnership that’s held fast since. NASA builds the satellites; USGS owns them after launch and archives the data.

The first satellite, called the Earth Resources Technology Satellite, was launched in 1972. It was renamed “Landsat” in 1979.

It carried something called a “multispectral scanner (MSS),” designed by a whip-smart toughie named Virginia Norwood, who managed a team of men in a time when she was often the only woman in rooms filled with engineers. Norwood’s device measured energy across multiple bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. Our eyes can only see red, green and blue light, but the MSS could “see” infrared and other bands, like a vampire bat, bed bug or a Predator from an action movie.

The MSS wasn’t even meant to be the primary imaging tool on that first satellite. It was supposed to be a camera, with the MSS as a backup. The camera broke, which turned out to be just fine. Scanning the spectrum offered more useful data than pictures anyway. Current Landsats have nine spectral bands and two thermal ones (awfully handy for studying urban heat).

But let’s get back to South Dakota.

In order to “catch” all that spectral data, the program needed a home somewhere within a narrow oval of Midwestern land between Kansas City and Fargo. The idea was to pick a place that would allow for the collection of data on either end of the country. The early satellites couldn’t store data, so the options were catch it or lose it.

Sioux Falls won the EROS race for two reasons beyond geography. First, South Dakota Sen. Karl Mundt was a pal of then-President Richard Nixon. Second, the Sioux Falls Development Foundation offered to give the USGS 300 acres of property free of charge.

Mayor Paul TenHaken praised their vision at a Friday reception at EROS, though he admitted that “we probably wouldn’t give away 300 acres today.”

In August of 1973, the doors flung open, and the EROS employees who’d worked out of a temporary office in downtown Sioux Falls walked in to begin building the field of satellite-based land change science.

Rapid advancements

Norwood, who I met in 2021, about two years before her death, was surprised by how quickly her idea began to help humanity understand its planet.

By the mid-1970s, scientists were using Landsat data to monitor crop health, after a wheat crisis caused the price of the grain to spike. When Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, Landsat was able to peer beyond the visible to track the damage and recovery. In 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster struck, and Landsat imagery was used to put the lie to Soviet assertions that it had been a minor event.

CBS News showed up for that.

Here’s the place in the story where I mention that EROS is about a lot more than Landsat. It has aerial photos dating back to the 1930s, data from NOAA and NASA satellites, declassified satellite photos from the 1960s and on and on.

All that imagery has contributed to more science than I have space to write about. There’s the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, which helps the U.S. Agency for International Development intervene with food aid in developing countries before people starve to death.

There’s the Hazards Data Distribution System and International Charter Space and Major Disasters, which have EROS ingesting and distributing imagery from natural and man-made disasters worldwide to emergency responders in the U.S. and around the world.

There are land cover databases, which define which parts of the country are cropland, forested, urban and the like and how they’ve changed over time. The first one ever made and the most widely used ones today were born at EROS under the guidance of South Dakota Hall-of-Famer Dr. Tom Loveland. EROS is also a partner in LANDFIRE, a land cover map with a dizzying array of detail on land cover, but also on potential fuels.

Lately, a lot of attention has been paid to evapotranspiration (ET), especially in semi-arid areas of the Western U.S. ET is the combined measurement of evaporation and transpiration, a measurement of water use efficiency that can help guide water use on farm fields.

Landsat can measure that at a wide scale. In a country that gets so much of its produce from places like California that don’t have a drop of water to waste, that’s a big deal.

The biggest deal of all came in 2008, when the USGS decided to stop charging for Landsat data.

That pushed other government agencies to open up their data. It also made it possible for companies like Google to ingest every image in the EROS archive, and for researchers to start analyzing decades of data. That’s the imagery you’d see on your phone, by the way, although the close-up stuff comes from commercial providers.

Data use exploded after 2008. At Friday’s anniversary reception, a scientist and Interior Department official named Annalise Blum appeared in a video to remind the staff and inform the guests that the decision to open up the archive and let others build with it and from it has translated into $3.45 billion in annual economic activity across the globe.

What’s next?

I’d be dishonest if I didn’t admit that Landsat has lost some of its luster since then. It’s still the most well-known and one of the most widely used data sources, but it’s not alone anymore.

Its satellites gather moderate resolution imagery in a world awash in higher-resolution stuff. It collects new imagery every eight days between its two operational satellites, while the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites, which collect higher-resolution data, get new stuff every five.

Commercial companies like Planet, which launch satellites the size of bread loaves by the hundreds, will sell you new imagery every day.

At the risk of being uninvited to EROS alumni gatherings, I’ll admit to telling my current coworkers that it’s now easier to find and download quick-and-dirty versions of American satellite imagery from the European satellite portal. For higher resolution stuff, I recommend the clunkier USGS interface, which has more and better stuff in a harder-to-understand format.

Real smart people don’t download data at all anymore, by the way. The entire Landsat archive is now in the cloud, and you can work with it all without downloading a thing.

But here’s the thing: All that work stands on a foundation built in Sioux Falls, and that work remains critical to a remote sensing world that’s changed so much since 2008.

EROS still catches data, fixes it, shares it and studies it, and that’s incredibly important work. Landsat is often referred to as the “gold standard” of satellite calibration, the data to which other satellite data is compared for accuracy. To do science over time and trust the results, every pixel of satellite data needs to be in the right place and measure the same thing every single time.

That’s really, really hard. To illustrate, imagine standing at the end of your block and taking a photo of a stop sign at the other end. Now imagine that you mark your spot, run around the block and take the same photo. Now imagine doing that 10 times. The chances that every pixel in every photo lines up exactly no matter how closely you zoom in are essentially zero.

Satellites circle the world, not the block. They’re hundreds of miles up, too, and they never stop to breathe or aim as they go.

The people at EROS were among the first to try and figure that out, and they’re still some of the best. People from all over the world would show up regularly during my time there to compare notes on the math magic behind it.

It’s also important to remember how important “free” is. Landsat has international ground stations and partners all over the world, sometimes in countries that could scarcely afford to pay a private company to collect data.

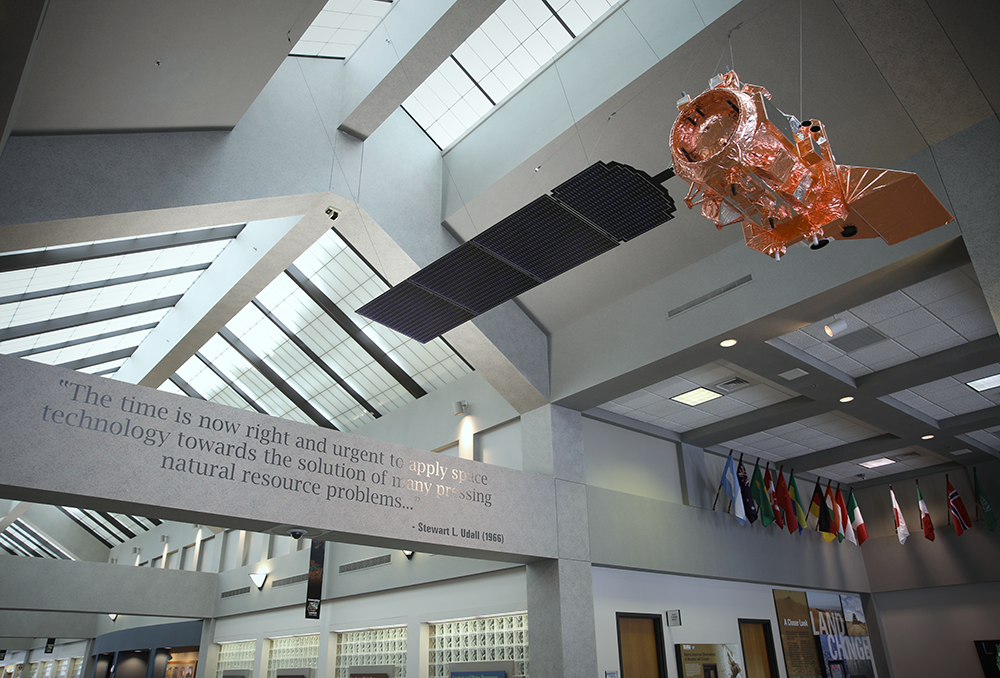

In remarks Friday, EROS Center Director Pete Doucette addressed the program’s place in the changing marketplace it helped create. He pointed to a 1:20 scale model of Landsat 9, the newest school bus-sized satellite in orbit, and told the crowd it stands as a symbol of what came before and what’s coming next.

A lot of modern satellites are the size of the model.

“Landsat 9 is probably the end of an era for that size of satellite,” he said.

Landsat Next, the successor to Landsat 9, will collect data across more spectral bands and will have a six-day revisit time, he told them.

It’s a far different project than the ones that built EROS. Put that together with the proliferation of other data sources, Doucette said, and there’s a fair bit of uncertainty ahead.

But then he pointed to a picture of Landsat 6, the one Landsat that never achieved orbit due to a fuel system problem. Risk has always been a part of the EROS story, he said.

As for the “cubesats” now watching the planet, he said, “we view these new and emerging systems with opportunity.”

“We don’t fear them, and we don’t feel we have to compete with them,” he said. “We relish the availability of that, because it complements what we can do. We are the Earth Resources Observation and Science Center, right? So anything that expands our ability to observe the Earth is something we need to consider as scientists.”

So yes, satellite data is everywhere. Private companies, universities, even high school classrooms can now buy and build satellites. Those satellites can hitch a ride on a rocket packed like a Boeing Airbus with other paying satellite passengers and join the thousands of satellites already in orbit.

It’s truly amazing.

And 50 years ago, South Dakotans you’ve never met at a place you’ve probably only heard of were among the first to lay the groundwork to make that reality.

Whatever the future holds for EROS, that’s a past worth celebrating.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: How EROS changed the world from a cornfield