How Bil Lepp interprets the legend of Oak Ridge prophet John Hendrix

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

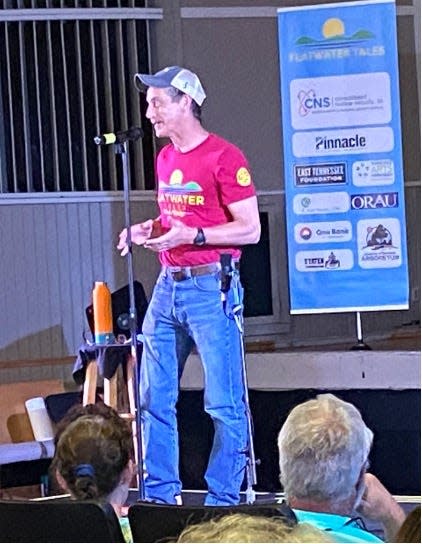

During his June 3 performance for the 6th annual Flatwater Tales Storytelling Festival in Oak Ridge’s Historic Grove Theater, renowned storyteller Bil Lepp gave his interpretation of the story of John Hendrix, the legendary prophet of Oak Ridge. I was honored to be able to help Bil with his research by providing a book I had written on John Hendrix and a video produced while I was at the Y-12 National Security Complex serving as Y-12 historian.

I also answered his questions as he prepared for the event. It was a delight to help him understand the nuances of the story. It is one that dates to the beginning of Oak Ridge in written form and by oral tradition before that.

Here is Carolyn Krause’s summary of Lepp’s story about John.

***

Storyteller Bil Lepp opened his narrative about John Hendrix, the legendary prophet of Oak Ridge, by giving part of a quote from the Bible: “We have not listened to your servants the prophets, who spoke in your name to our kings, our princes and our ancestors, and to all the people of the land.” _ Daniel 9:6.

His point was that maybe the people living in the Oak Ridge area where John lived decades before the start of World War II should have taken his prophecy seriously if they knew of it.

Lepp reminded his audience that 3,000 people living in what became known as Oak Ridge were forced to leave their homes and lots in 1942. The reason: the government had chosen the site for nuclear fuel production plants for the Manhattan Project to help win World War II. Some of those unfortunate residents had been kicked off their property previously in the 1930s when the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was established and when TVA built Norris Dam.

Wherever they lived, Lepp said, “The government said, ‘Go!’ I don’t know where they went, but I would have left Tennessee, I’ll tell you.”

Lepp read John’s prophecy that he made in 1900 about the future of the Oak Ridge area. Here is the essence of the prophecy: “I’ve seen it coming. Bear Creek valley someday will be filled with great buildings and factories, and they will help toward winning the greatest war that will ever be.”

John mentioned that “the center of authority” would be in “a big city on Black Oak Ridge.” He concluded that in his envisioned great city “big engines will dig ditches and thousands of people will be running to and fro. They will be building things and there will be great noise and confusion and the earth will shake. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it coming.”

If the residents of Black Oak Ridge had known about John’s prophecy when the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 caused the United States to enter the war, Lepp suggested, they might have prepared to take action to protect their property.

“I’m not saying that the people who lived here wouldn’t have supported the war effort,” he said, “but maybe they could have formed a homeowners association to help the people get a better deal for their land.”

He noted that Curtis Hendrix, John’s son by a second wife, received only $850 from the government for the 60 acres of land he owned in Black Oak Ridge. He and 1,000 other families were shocked in 1942 to read the heartless message in the Declaration of Taking letter.

Lepp said that the federal government “put a fence around the city and the only way you could get back in is if you died.”

He was right; Gen. Leslie Groves decided that the Oak Ridge cemeteries must be protected; many of the living were evicted, but not the dead.

“So,” Lepp said in jest, “you could be buried in your family cemetery, but before you could come back in, they opened your coffin and inspected it to make sure you weren’t up to no good.”

Lepp explained that the federal government selected the Oak Ridge area as a site for the development of the war-winning atomic bomb because of the availability of water, electricity from Norris Dam and ridges and valleys that allowed separation of the nuclear fuel plants.

“If one factory exploded,” he said, “the damage would be contained to just that valley and the whole thing wouldn’t go off like a chain of firecrackers.”

Oak Ridge grew fast; in three years some 75,000 people lived here. Available to them were a library, symphony orchestra, sports complexes, seven movie theaters and worship services for 17 different denominations.

“You got 17 church services, and you got 17 restaurants and cafeterias, so they just rotate so nobody has to fight over who gets served first on Sunday,” Lepp said.

He then told the story about John Hendrix that many Oak Ridgers know. John was born on Nov.11, 1865, right after the Civil War, making him a "Baby Boomer," Lepp speculated. In 1888, he was married.

Hendrix and his wife had four children. In 1900, their two-year-old daughter Ethel died. John’s wife blamed him for her death because he had punished her; however, she may have succumbed to typhoid fever or tuberculosis. Angry at him, his wife left and took the three children to Arkansas.

Distraught by his daughter’s death and the departure of his wife and children, John turned to religion and prayed to God to show him the future. He was told to go into the woods and lay his head on the earth for 40 days and 40 nights so that the future would be revealed to him. One woman heard him wailing as he prayed on a wintry day and saw that his hair was frozen to the ground; so, she gave him a blanket and chicken soup. Lepp said from what he read it was not clear to him whether the prophecies came all at once or over time or whether John took more than one pilgrimage into the woods over the 40 days.

Besides his Oak Ridge prediction, John prophesied correctly that the L&N railroad would be coming into the area and that cargo would be carried through the air. The latter prophecy was made before the airplane was invented. He made another prediction after he escaped from a “poor house” institution to which he had been committed by neighbors who considered him crazy.

John said that this “was an evil place and that God would burn it to the ground in 30 days.” Within a month lightning struck and burned down a building in the area. But it may not have been the institution where John had stayed, Lepp said, because it did not close until 1968.

In 1909, John married his second wife, Martha Jane, and their son Curtis was born. John worked hard on the 15 acres of land he had bought in Black Oak Ridge by laboring for 50 cents a day to pay off his owner. Then he became ill with tuberculosis, so he moved to the cabin on the property so as not to expose his wife and baby son to the disease.

He was cared for by his stepdaughter, Paralee Raby, daughter of Martha Jane and wife of Perry Raby. Lepp expressed admiration for her because she raised the baby of a man whose wife died in childbirth and cared for many neighbors afflicted with diseases that Paralee never caught. She “loved her neighbor as herself,” wrote her adopted daughter, Grace Raby Crawford.

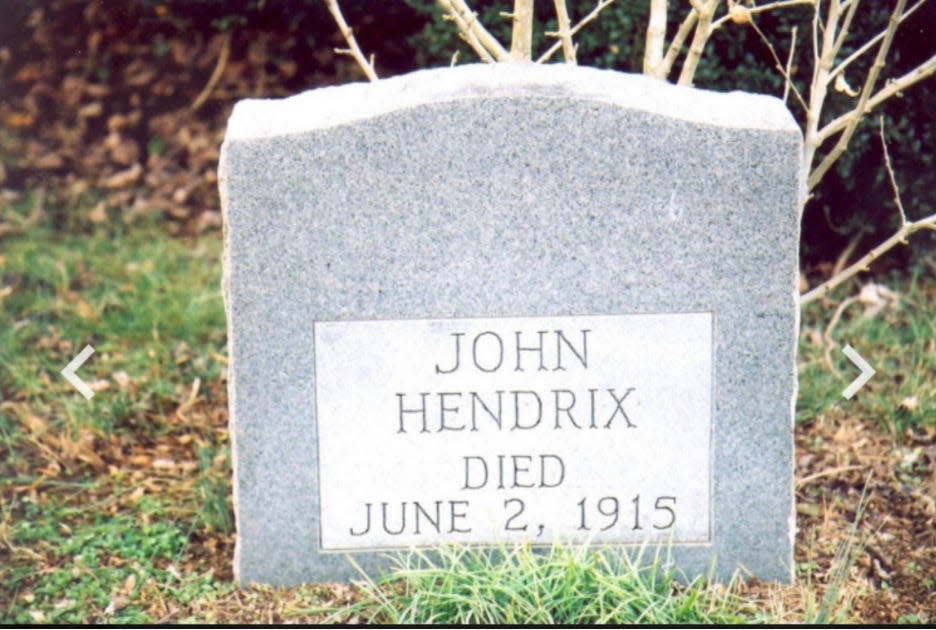

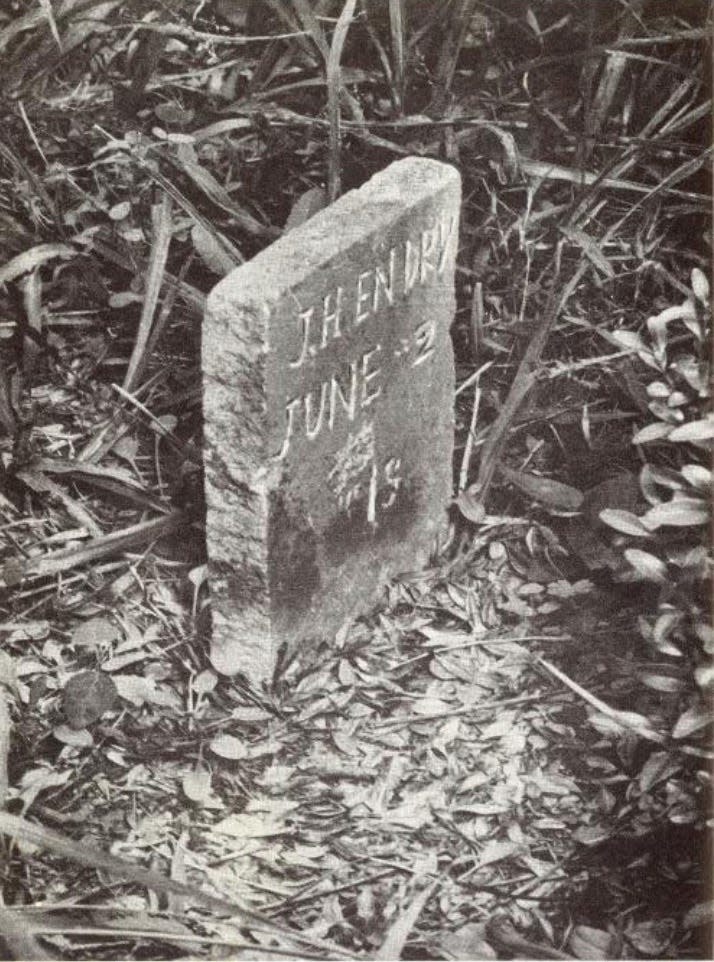

John Hendrix died in 1915.

“His last request was to be buried on the hill overlooking his farm and his apple orchard so that he could watch the thieves,” Lepp said. “I wouldn’t go steal apples from that orchard.”

Perry bought a $8 custom-made coffin for John that he paid off in three years. For $20, Perry bought a house on the farm next to the one John had. In 1942, Paralee, like Curtis, received the government notice demanding that she move away in six weeks.

In trying to discern the lesson from the legend, Lepp asked, “Why did God give this prophecy to John?”

After all, it didn’t help the prophet or his immediate family profit long on their land. Assuming that John made the Oak Ridge prophecy (and there are doubts about that), Lepp said the lesson is that “we don’t listen to prophets that tell us things we need to hear. We ignore them for whatever reason.” And if the John Hendrix story is not completely true, Lepp’s conclusion is, “That’s how folklore works.”

***

Thank you, Carolyn, for attending the Flatwater Tales Storytelling Festival and capturing Bil Lepp’s rendition of the John Hendrix story. It is one I tell everyone who comes to Oak Ridge and is included in all my presentations and tours about Oak Ridge history.

This amazing story was first introduced to me by Ed Westcott. He sent me a photograph of the original tombstone. The one that is there now was placed there by Dorothy Bruce and her 1966-67 Jefferson Junior High School students.

For more information read: http://smithdray1.net/historicallyspeaking/2006/5-30-06%20Joe%20Oakes%20article%20on%20John%20Hendrix.pdf

This first written story about the legend was published on Nov. 2, 1944, in the Oak Ridge Journal. Until I found that publication, the earliest publication I knew of was in George Robinson’s "The Oak Ridge Story" published in 1950.

Ed also told me about a man who knew John Hendrix, Clay Seals. Read about that here: http://smithdray1.net/historicallyspeaking/2006/4-24-06%20John%20Hendrix%20-%20Clay%20Seals%20by%20Ed%20Westcott%20part%201%20published%205-2-06.pdf

D. Ray Smith is the Oak Ridge city historian and a columnist for The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: How Bill Lepp interprets the legend of Oak Ridge prophet John Hendrix