A bill aims to change Native American history in schools. How does it look now?

In most Michigan schools, Native American history has been taught for decades. But increasingly, teachers and tribal leaders say that history is incomplete — and often inaccurate.

As increased awareness comes to Indigenous history throughout Michigan, educators are reimagining their curriculum.

"What we are taught is revisionist history," said Kevin Leonard, a Holt Public Schools parent, board trustee, and member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians who works as a diversity director at Michigan State University. "...We don't talk about the darker aspects that existed well beyond the end of slavery."

Local tribes and legislators are working to change that.

Last month, Michigan Sen. Wayne Schmidt, R-Traverse City, partnered with tribal leaders to introduce Senate Bill 876, which would encourage lessons about Native American boarding schools in Michigan classrooms. Those residential schools, where Indigenous children were sent to assimilate to European culture and sometimes abused, existed in Michigan into the early 1970s, later than most places.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's 2023 budget earmarks $500,000 for a yearlong study on those boarding schools after an unmarked mass grave was found near the site of a residential school in Canada last year.

More: New bill proposes lessons on Native American boarding schools in Michigan classrooms

More: A culture eradicated: Michigan Anishinaabe recall abuse, erasure at state boarding schools

Melissa Kiesewetter, tribal liaison for the Michigan Department of Civil Rights, cited a study by the nonprofit IllumiNative that found nearly 87% of national history standards in the 2011-12 school year didn't cover Indigenous people after the year 1900, and 27 states didn't name any individual Native Americans in their standards at all.

"That right there is telling us that schools and the educators within the schools, if they are relying on their textbooks, they only have for the most part pre-1900 references," Kiesewetter said.

Outside the classroom, the Michigan Native American Heritage Fund has helped schools and local governments amend their use of Native American imagery and. That includes more than $200,000 it paid Okemos Public Schools to help rebrand after the district did away with its 'Chiefs' nickname last year.

More: The Okemos Chiefs face a name change 30 years in the making

"I don't think a lot of our kids have an appreciation for the tribes that were in Michigan," said William DeFrance, Eaton Rapids Public Schools superintendent. "When you get up near the U.P., that's just the part of Michigan that I don't think kids think a lot about."

How do Michigan schools teach Native history today?

Jessica Cotter, executive director of curriculum at Holt Public Schools, said the State of Michigan uses a social studies model called "Expanding Communities" to teach history.

"Michigan history is taught to third graders, and there is big components in the standards around economics, government, geography, the geography of the state, and just helping them understand what a state is," she said.

But increasingly, teachers are introducing literature that challenges those standards. Both Leonard and Lauren Reed, a history teacher at Grand Ledge High School, are fans of "Lies My Teacher Told Me," the 1995 book by James W. Loewen examining 12 popular American history textbooks. Both praised the book for presenting the nuances of topics like the Columbian exchange for all ages.

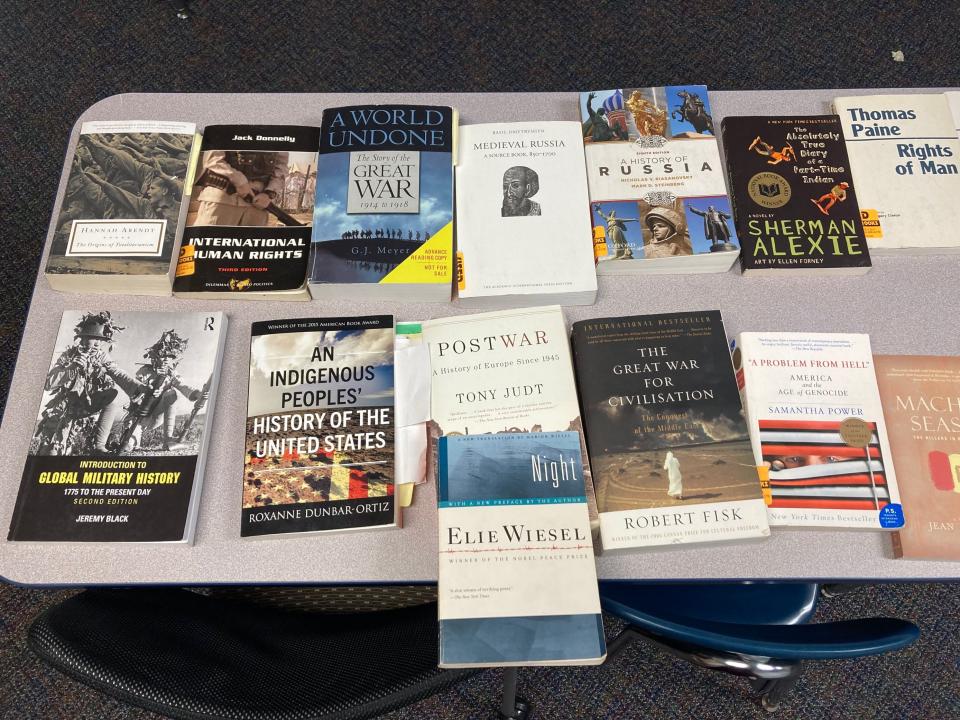

Reed has also used "An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States" in her classroom. The 2014 paperback by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is one of five in a series interpreting American history from the perspective of marginalized groups. Reed also tried bringing local Anishinaabe into her classroom to speak, but the pandemic halted those plans.

Today, she teaches lessons on Native American involvement in U.S. wars in an attempt to gain citizenship, the forced assimilation of Indigenous people, and the effects of colonization on them. She begins by surveying students' existing knowledge of those subjects.

Most students, she said, come in having learned about the Trail of Tears, but without the understanding that it wasn't an isolated incident.

"They need that time to adjust to it, to see that there's more than one event and how this actually looks in policy leading up to World War I," she said.

Though tribal members involved with Schmidt's bill agree that lessons on boarding schools should be taught, they disagree on the degree of depth and at what age.

Kim Fyke, a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, believes children of all ages should learn the history as a means of preventing it from happening again. Meanwhile, Linda Cobe, of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, thinks it would be more appropriate for middle and high schoolers. Both are survivors of a boarding school in Harbor Springs themselves.

"It's a more appropriate grade level where they have their age of reasoning and understanding," Cobe said.

Cultural tradition: Anishinaabe honor the dead at annual ghost suppers

Jamy Marske, a history teacher and department chair at Eaton Rapids High School, uses Alfred Crosby's book "The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequence of 1492" and Bernal Díaz del Castillo's memoirs in the classroom. He also addresses Native American stereotypes throughout history and draws on his days as a student at Central Michigan University.

"Seeing the close relationship we have at that university with the Chippewa tribe," he said. "It gives me a different perspective to teach the kids about the different stereotypes and how to avoid those stereotypes."

He hopes to help his students understand why history is taught the way it is, and why language surrounding Indigenous culture often wrongly portrays it as a thing of the past.

Keeping the language alive: Anishinaabemowin class aims to save Michigan's first language

Leonard points out that Michigan social studies standards suggest lessons on genocide — the school code uses the examples of the Holocaust and Armenian Genocide — and most teachers move on chronologically from there. But doing so tends to gloss over Native American history during the 20th century, including the American Indian Movement in the 1960s and the boom of Native gaming and casinos.

"It reinforces the message that we're not here anymore," he said. "(That) we didn't or we don't matter anymore because we're not here, we're gone or our populations are just so small."

He continued: "Post certain (eras), whether it's the Industrial Age or whatever you have, I think some of it's convenience. We got a lot that we need to teach, and it's just easier to focus on these white Eurocentric ideologies than it is to continue to talk about the impact that tribes had on everything."

To combat that oversight, both Eaton Rapids and Grand Ledge teach about Native American news and current events, such as the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, the debate surrounding mascots in sports, and the McGirt v. Oklahoma U.S. Supreme Court case.

Even more changes can come if families get involved, Leonard said.

"(We need) not just your BIPOC families, but the majority of families to say, 'We really need to teach our kids the reality of what's going on,'" he said. "We still have a contingent that for some reason doesn't want that taught."

Support local journalism and get unlimited digital access! Subscribe for only $1 for six months!

Contact reporter Krystal Nurse at (517) 267-1344 or knurse@lsj.com. Follow her on Twitter @KrystalRNurse.

This article originally appeared on Lansing State Journal: Teachers broaden Indigenous history lessons beyond Michigan standards