Bill would compensate towns that help keep Quabbin Reservoir clean

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A social media post about Boston's water winning a taste contest alerted the Western Massachusetts legislator to the fact that residents of Greater Boston had no idea where their water came from: the Quabbin Reservoir in her home district of Hampshire, Franklin and Worcester.

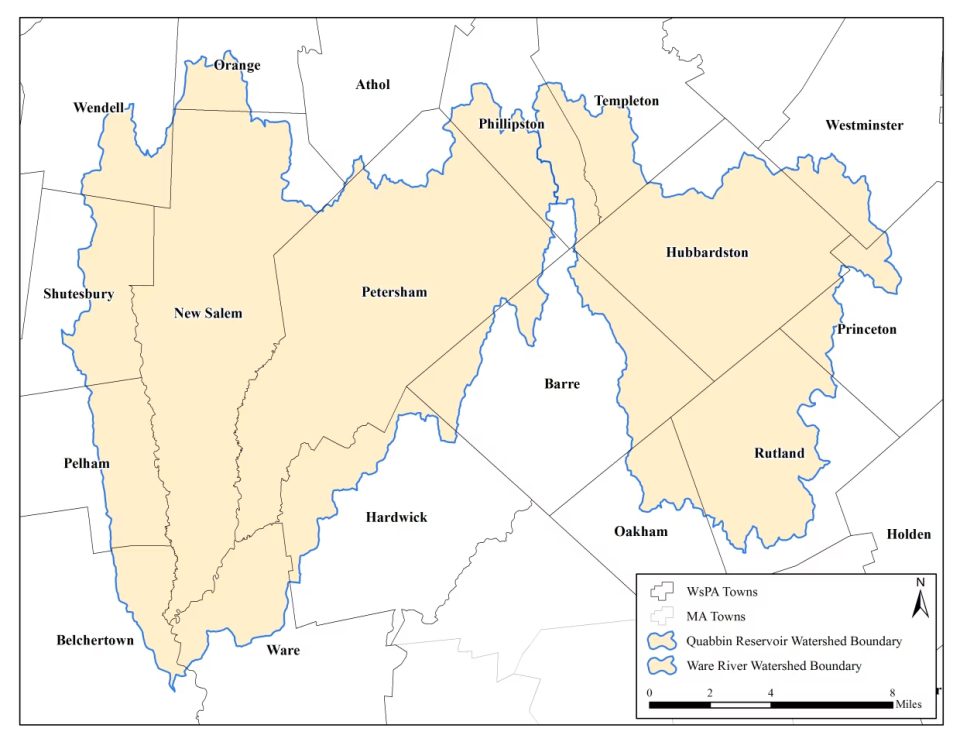

The legislator, Rep. Jo Comerford, D-Northampton, along with Rep. Aaron Saunders, D-Belchertown, filed legislation that seeks to compensate the communities adjacent to the reservoir, created by the flooding of the Swift River Valley in 1939, for acting as stewards of the watershed to keep its 400 billion gallons pristine.

The measure would also direct the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, the governing body of the reservoir, to explore allowing those same communities access to the water for their homes, businesses, schools and public buildings.

Currently, the communities that care for the watershed do not draw water from the Quabbin.

Why aren't local towns tapping local water resource?

Was it an oversight that boxed them out? Lack of foresight? Engineering challenges?

“I don’t want to speculate about the thinking at the time, but the communities never received an invitation to join,” Comerford said. They have no access to the water, Comerford said, no voice in the MWRA, and there has been no fair recompense for the social and economic devastation caused by the construction of the Quabbin.

Sean Navin, public affairs director for the MWRA, said he was unaware of any prohibition barring local municipalities tapping into the Quabbin at the time of its construction. He speculated that due to their rural nature and small size they may have lacked the public water infrastructure to hook into the system.

“They may not have had a need for a public water system,” Navin said.

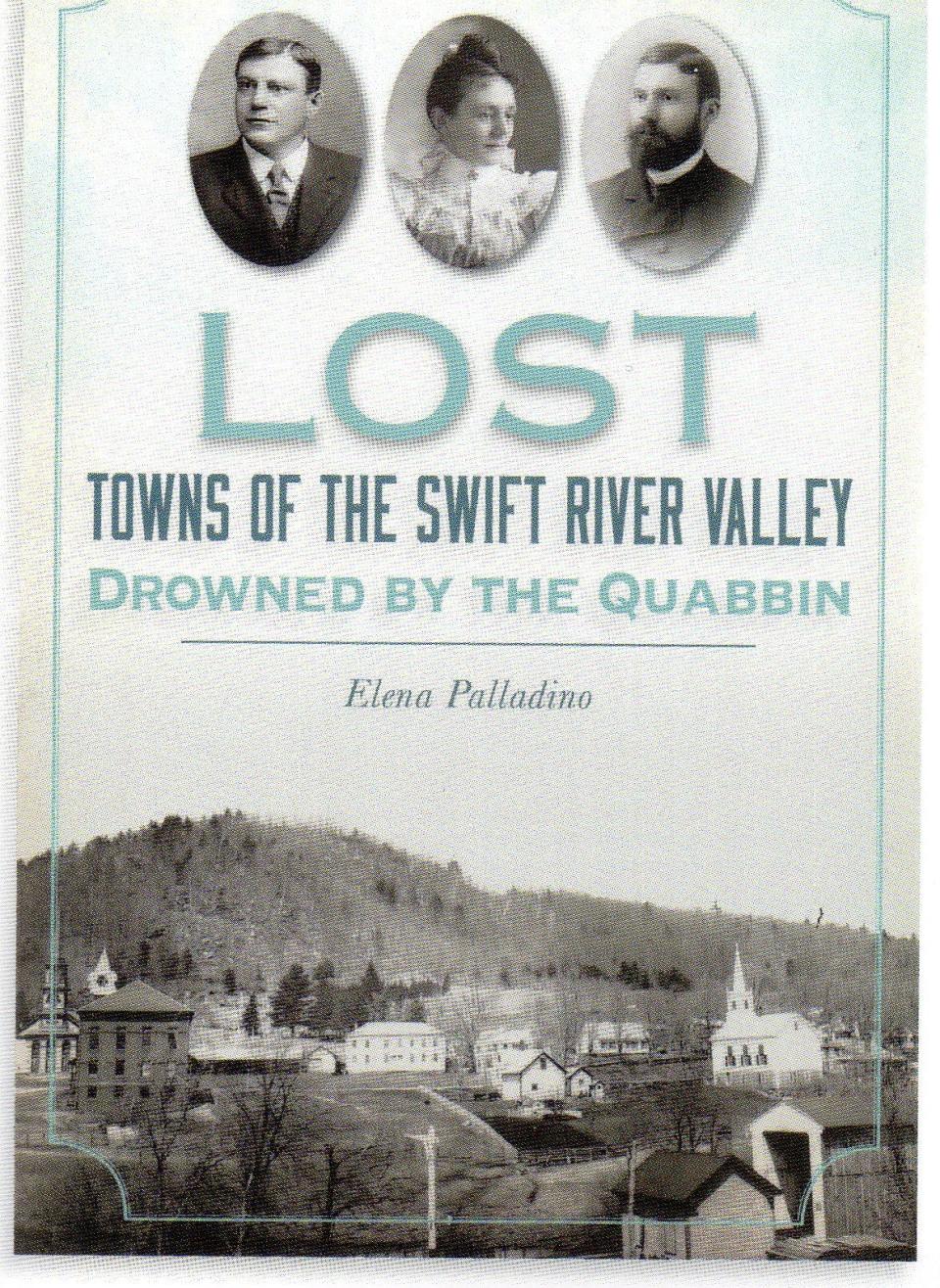

A recent book about the construction of the reservoir, “Lost Towns of the Swift River Valley Drowned by the Quabbin” by Elena Palladino, gives a human voice to the decades-long process that was finally completed in 1939.

In her book, Palladino tells the stories of three local residents — Marion Andrews Smith, daughter of a prominent family three generations strong in the area; Willard “Doc” Segut, a local doctor; and Edwin Henry Howe, postmaster and general store owner for the town of Enfield — as they grappled with the loss of their communities.

Four towns 'lost' to build Quabbin Reservoir

Lost under the waters of the Quabbin, from the native Nipmuc word meaning “many waters,” are the communities of Enfield, Dana, Greenwich and Prescott. Greenwich was a summer community and Prescott a farming one. Dana manufactured palm-leaf hats, Shaker bonnets and soapstone footwarmers, according to Karen Warinsky of the Quabbin Reservoir, Swift River Valley Historical Society.

During the time between the inception of the idea in the late 1800s and the completion of the reservoir, the state acquired the land, disincorporated the four municipalities, deconstructed the communities and cut down the forests to make way for the reservoir that serves Greater Boston and surrounding communities in Eastern and Southeastern Massachusetts.

“The people who I represent remember living in there, or they have heard the stories,” Comerford said. “The effects still ripple through the area — the sacrifice they made for the Quabbin.”

The Quabbin and ancillary reservoirs in the system serve more than four dozen communities in the eastern part of the state. The Chicopee Valley Aqueduct, also maintained by the MWRA, serves communities in Western Massachusetts. New member communities are welcomed into the MWRA network regularly, with Burlington being the most recent to join, in September.

While there has been a $4.3 million buy-in fee charged municipalities as they join the network, the board of directors voted to temporarily waive the fee for municipalities seeking to join under certain circumstances in 2022, said Katie Ronan, a project manager with the MWRA.

Those factors include issues, including pollutants, in existing local water sources, whether the local sources constrain development and whether they are located in a stressed basin, as defined by the state Department of Environmental Protection.

The temporary waiver runs through the end of 2027, Ronan said.

Tapping into Quabbin along border towns

The MWRA has already agreed to the portion of the bill requiring it to explore the mechanisms that would allow communities that border the Quabbin to tap into the reservoir’s water.

“Over the past year, the MWRA has done some studies concerning system expansion and where access to the Quabbin water could be delivered to communities on the North and South shores, midwestern sections of Massachusetts and communities in the Quabbin watershed,” said Navin.

The result may be different from how the MWRA provides water in the state’s densely populated eastern reaches where water infrastructure already exists, Navin said.

Water from the Quabbin travels through more than 100 miles of large pipes buried 200 feet below the surface of the earth. It travels first to the Wachusett Reservoir, then into communities throughout Eastern Massachusetts.

Another feature of the bill would create a special $3.5 million fund to be used by the watershed communities to support their social and civic expenses. The funds could also be used for nonprofit organizations directly serving the health, welfare, safety and transportation needs in those communities.

The legislation would afford local residents more say in the governance of the MWRA, with three seats on the authority's board.

One of the most important provisions would address the formula through which the watershed communities receive revenue for lands in the public domain. The MWRA has purchased large swaths of land near the reservoir to preserve the purity of the water, and it pays communities an amount to make up for what might have been generated by local real estate taxes.

“The program pays watershed communities in the MWRA more than $8 million a year,” Navin said.

Comerford’s bill seeks to include the land under the water in the calculations, in addition to the land in the protected watershed area.

“It’s a big job, keeping the Quabbin clean,” Comerford said, adding that local communities should be compensated for the work they do.

The towns that border the reservoir include Hardwick, Ware, Petersham, Belchertown, Pelham, Shutesbury and New Salem.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Quabbin Reservoir Act would compensate adjacent towns