Bill Irwin, the Clown Who Conquered Broadway—and Samuel Beckett

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The clown still lives within Bill Irwin. You can see this at New York City’s Irish Repertory Theatre where Irwin, a movie, TV, and Tony-winning theater actor and pre-eminent interpreter of Samuel Beckett’s work, is playing Clov in Beckett’s Endgame (to March 12), the jittery servant of the blind, domineering Hamm (John Douglas Thompson). Clov’s body looks painfully elastic and broken, his limbs just about carrying him across the stage and up and down ladders at physically jarring angles.

What ecological catastrophe has occurred outside? What of Hamm’s parents, Nagg and Nell (Joe Grifasi and Patrice Johnson Chevannes), dwelling like pop-up figures in garbage bins to the left of Hamm’s wheelchair? Is there any way out for any of them? Do they even want to leave? As ever with Beckett, the interpretation game is all yours.

Irwin’s life and career have been as fascinating as the dense thicket of Beckett’s words. He won a Tony Award playing opposite Kathleen Turner in Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? on Broadway; his solo stage show On Beckett is an illuminating master-study of Beckett’s work and themes.

He has also appeared alongside Robin Williams, Steve Martin, and Sally Field (twice, most recently playing her husband in Spoiler Alert). You may have seen him on TV—in recurring roles on Elmo’s World (as Mr. Noodle) Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, and Legion—yet because he is such a chameleon in much of his work, he enjoys both freedom and variety in what he does. Typecasting is not an actorly affliction he has suffered from.

Even Bill Irwin Says Clowns Are Scary

Irwin was most tickled recently when, walking just the few blocks from his Flatiron apartment to Irish Rep, he was aware of someone walking near him—and was concerned he might be physically vulnerable to attack should said person be crazy. Instead, the person shouted out merrily, “I love your work!” Very New York, and very Bill Irwin, all rolled up into one.

Irwin is 72, and looks decades younger. His striking good looks come from his mother Elizabeth, he says, smiling; having to watch his diet is a legacy from his father’s side of the family. A wry storyteller and muser by nature, anecdotes beget anecdotes. He is curious about everything, interrogating his own words in real-time and heading down another conversational byway as a result.

The eldest of three children, with a father (Horace) who worked in the defense industry, Irwin grew up all over, including Tulsa, Oklahoma, and California. His mother was a high school teacher who later sold real estate.

Asked aged 7 what he’d like to do when he was older, Irwin had replied an architect or or be in the army—“This was coming out of the 1950s, and Elvis had gone into the army.”

Bill Irwin accepts the 2005 Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play for Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf at the 59th Annual Tony Awards show at Radio City Music Hall in New York, June 5, 2005.

There wasn’t much live theater in Tulsa, Irwin recalled, “but we went to the circus every year. That was an influence that struck me.” He liked sports, but ultimately “sports weren’t as interesting as performing.” He recalled, aged 7 or 8, his first school show—playing one part of a boat, “and one of the mothers saying how funny it would be if I jumped out of the boat, and by destroying the illusion of the boat, I remember getting the laugh.”

Abbott and Costello’s famed baseball-based sketch “Who’s on First” was an early touchstone. “I saw it as a kid, and it’s one of the great pieces of American comedy, all about miscommunication.”

In high school Irwin performed in a Molière play, which involved a lot of mugging, “which would embarrass me now for sure.” (Much later, as an adult, he adapted the playwright’s Les Fourberies de Scapin off-Broadway.) A girl at school told him he would go into television. “At the time, I thought, ‘How does one choose that?’ Now I see that actors do pursue such a thing. At the time I thought it was beyond me.”

“Don’t get an old fart started,” he told The Daily Beast, as the stories began to roll forth. “I have not been back to Oklahoma since 1959. I keep looking for a job to take me there.”

His father—who died at 100, his mother at 93—were supportive parents who watched their eldest son in the 1960s enter the arts. (Later, he would perform clowning for his father and the other residents of his retirement home. “Samuel Beckett was crazy,” his father would say.)

As a young boy, “television was our portal,” and he was inspired by watching Jackie Gleason and Art Carney, “and other people who fell down and got back up again. Gleason, Carney, Buster Keaton, Lucille Ball. I watched the way they moved, and also the structure of their shows. Within one half-hour there was the best of Molière without all the jabber.” At university, Irwin came to realize how great Molière was, adding, “it just takes some time to see its structure working. That’s what is maddening about Beckett. The patterns are intricate, but not conventionally definable.”

Growing up, Irwin’s parents told him to pursue his passions but with the “resignation and concern” with which so many parents of would-be actors send their offspring off into such a professionally precarious world. “Today, I teach students, and parents ask about the chances of their kids becoming professional actors. Well, it’s not that high, but it’s good a training as any in this gig economy.”

During an exchange year in Belfast aged 18, he lived with a Quaker family and studied A-Level History, English, and Spanish. He wandered around the city late at night, deflecting trouble with other youths with his then-still-exotic American accent. He played Edgar Linton in a school production of Wuthering Heights.

Back in America, Irwin attended UCLA and became a theater arts major, though circus was not yet his passion: “I wasn’t longing to get me some baggy pants, but it must have been latent.” He learned to study scenes and scripts, and began to study and perform clowning in his early twenties, attending Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College. He had felt “stultified” by some of the classical theater he was studying at Oberlin College. “Circus was for actual people. Clowning offered a way to look at the surreal,” Irwin told The Daily Beast. “I still like to put on a long coat and impersonate having no feet and a shrunken body.” He smiled. “Although I can’t sustain it for long on my knees now.”

“What I love is the comedy of the body,” Irwin told my colleague Malcolm Jones in a 2016 interview. “It’s a little highfalutin’, but you can even say pre-verbal comedy. People laugh differently at stuff that isn’t brought to them via the spoken word. It’s from a different place, it’s a different quality of laughter. And the craft is different in that, if you’re doing comic dialogue, you have to get the line in and wait for the laughter to die, assuming there is any, and then fit the next line in and wait for it to register. But with comedy of the body, when it’s working right—that’s a wonderful place you work toward, you don’t always get there—laughter comes without the last laugh having died. But that’s only a superficial difference. I really think it’s a different kind of release, watching the body being the subject of comedy.”

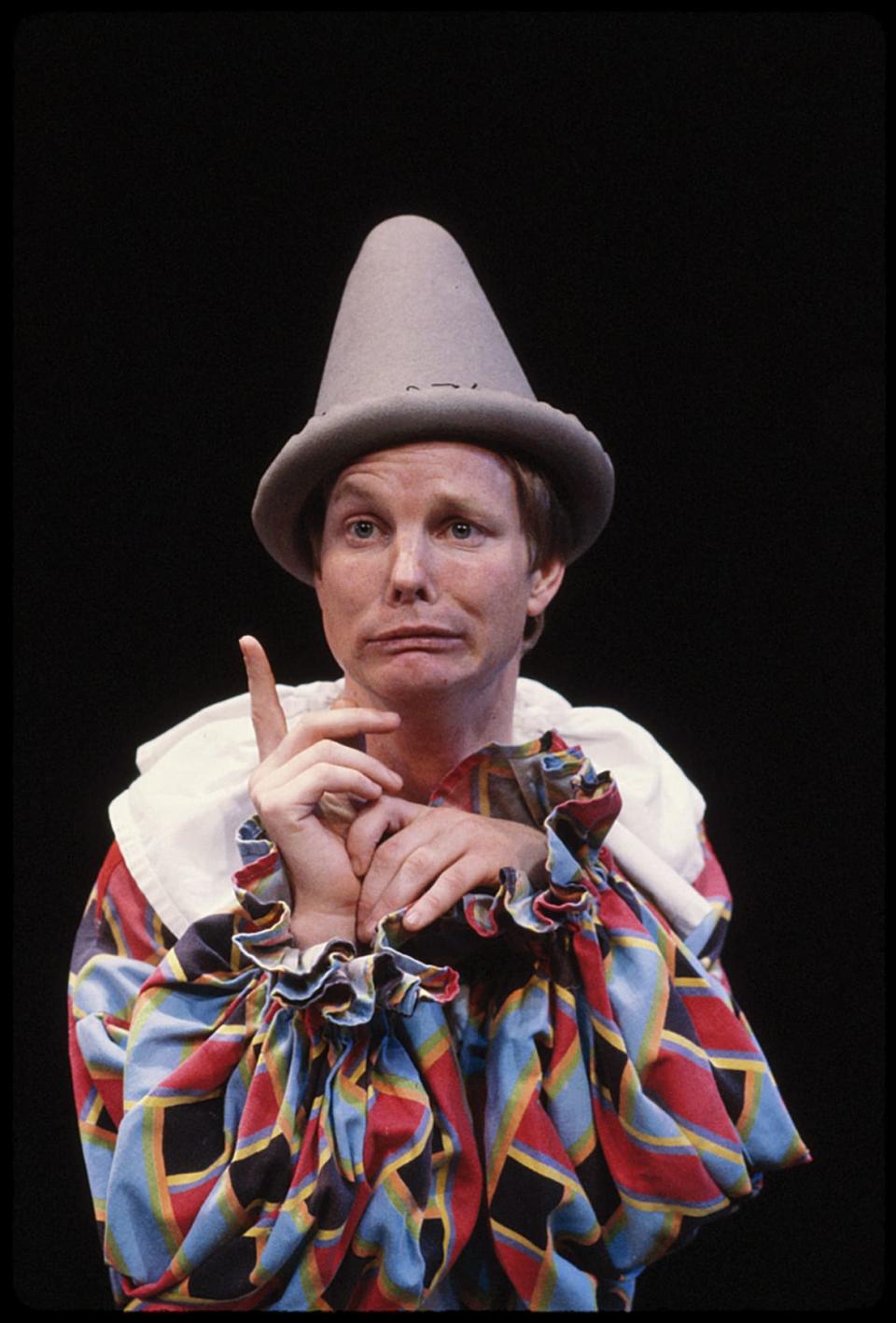

Bill Irwin in 1982.

In 1975, Irwin helped found the Pickle Family Circus in San Francisco (he recalls seeing slain LGBTQ icon Harvey Milk waving at passersby from the window of his shop Castro Camera). With collaborators Doug Skinner and David Shiner, Irwin became one of the pre-eminent stage clowns in the business, with shows like Mr Fox: A Rumination (2004) and the acclaimed revue Old Hats (2013), which also featured the lyricist and composer Shaina Taub.

Doing solo clowning is difficult, he said. He and Shiner “made each other look better, and it’s the best way to sustain an evening of clowning. At the beginning he could be the bad guy, and I’d be apologizing for him. Later we would switch, and I would be the maître d’ trying to steal his date.”

Clowns, Irwin knows all too well, can also inspire fear. “You can feel it— and it is has a name, coulrophobia—in a room of kids, oh God yeah,” he told The Daily Beast. “At least they’re not bored. It’s a deep response, and when you see it you know you have to win them over.”

Irwin’s career grew and diversified on both stage and screen. He starred opposite Robin Williams on film in Popeye (1980) and as Mr. Leeds in M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water (2006). He played Anne Hathaway’s father in Rachel Getting Married (2008), and appeared (as Lucky) opposite Williams and Steve Martin in Waiting for Godot (1988); with Turner in his Tony-winning …Woolf (2005); alongside Sally Field on stage in Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? (2002), and opposite Denzel Washington in The Iceman Cometh (2018).

“Kathleen (Turner) is a force of nature,” he said. “She was at the opening of Endgame the other night which was lovely of her. And she saved my ass more than once when I forgot my lines doing Woolf.”

Despite winning a Tony (and other awards), Irwin says a show or movie “can change your life” rather than theater’s most prestigious award. He laughed that Liz McCann, Woolf’s “great” producer, “loved to both elevate you and keep you grounded. She told me, ‘Every day you should be grateful that Kevin Kline said ‘no’ to this.”

Irwin met both Albee and Beckett—with advancing age and frailty, the former a gentler bear than his irascible image suggests. Irwin met Beckett in Paris towards the end of his life, just as Irwin was preparing to play Lucky. “I think he was disappointed. I was so nervous. We were both shy people, actually. I have a memory of his hands being more vivid than his face. He was very deferential. He asked if I had children, and I said I hadn’t yet. More than once I wondered what we were doing there. Then he said, ‘I’ll leave you now’—that very Irish way of saying, ‘I’m off.’”

Irwin said he has enjoyed traveling rangily between between screen and stage. Of fame and celebrity, Irwin said that both “are the great unknowables of our profession. Do people choose them? I worked with Robin Williams and Steve Martin on Godot. Both are incredible, and very nice, celebrity icons. Being around them was fascinating to see how they dealt with those things. For me, it’s both a conscious and unconscious embrace. I would say to myself, ‘I don’t want that,’ but also ask myself if fame and celebrity are a measure of being really good, especially if it means your life is circumscribed by them. I don’t know the answer.”

“Like any actor,” Irwin said, he also can’t answer if he feels fulfilled. “Sometimes you feel your professional life hasn’t amounted to much, at other times I feel as if I am making the best contributions as an actor I can make—not as a star, and I’m not sure as a journeyman, even though I am not sure what that terms means or should mean… but as a working actor.”

Robin Williams, said Irwin, “was incendiary. People would say, ‘He’s brilliant, but I can’t be around him. He’s exhausting.’ I had great empathy for Robin. He was driven crazy in his mind. He both wanted normalcy, but didn’t want it at the same time. I don’t mean that in any denigrating way at all. As a stand-up comic he was a warrior. He would come back victorious, or come back broken.”

Irwin laughed, recalling the early Godot audiences, which included elderly subscribers. “The set included a beautiful lot of sand. The people in the first rows were well-lit. If he saw people dropping off, it drove Robin crazy. I think he would much rather have been heckled by audiences than see them fall asleep. And so he kicked sand in people’s faces if he saw them nodding off. Steve (Martin) has a different kind of brilliance, although the real star for me was (director) Mike Nichols.

“One day, he asked us all if we had experience with a certain kind of dog that one of his kids wanted. As soon as he said that, Robin started acting the dog. Everyone belly-laughed. Steve was watching too. After Robin had stopped playing the dog, Steve just said, ‘Well, they’re great dogs, but don’t ever give one a loaded gun.’ It was an interesting competition between them both. One of the understudies was David Hyde Pierce (who went on to find fame playing Niles in Frasier), and we would just sit there and watch them both.”

“I have to do clowning justice”

Clowning, even if not visible, has been useful for so many of Irwin’s roles, whether enlivening moments of storytelling on stage, or in the strange and surreal physical aptitudes he needs for shows like Endgame, where his hunched body speaks of the themes—confinement, the need to escape—within the play itself.

“Many people see Endgame as an exercise in musical tedium,” Irwin told The Daily Beast. “While we hope you see a beautiful treatment of that, we also want to break that up. The characters in the show could be real, and living in an old house with an ecological disaster happening outside the walls, or you could see them as components of an actual consciousness—as well as anything else you want in the Rorschach sense: the need to be self-loathing, the need to be abased, the need for connection, the need for love.

Bill Irwin in Endgame.

“After our first reading, John said, ‘It’s a love story,’ so we also approach it that way, not just he as the master and me as the servant. Or you could read it as ‘life is unbearable.’ Or as, someone else said to me, it’s a play about people who can’t say goodbye to one another. Its characters are saying all kinds of things. ‘I have to get out of here.’ ‘I want you to want me here.’ ‘I want you here.’ ‘I want you to give me something, but you’re not doing so, so I’m going to leave, but I can’t leave.’ ‘Do you want me?’ ‘Do you want me to leave?’ Should I stay, or go?’”

In previews, Irwin had wondered what Clov had really seen in the outside world in the closing minutes of the play—whether he sees something or is fabricating seeing something. As with so much in Beckett, Irwin doesn’t have an answer, but his skill as an actor in that moment is to leave space open for a variety of interpretations.

Irwin said he missed clowning, and may return to the stage to do it. “But with caveats. I have to do it justice, like do a masterwork evening of clowning, or be invited to do it as an entrée to a bigger show.

Irwin has been surprised to see audience responses to Endgame vary so widely audience to audience—laughter in different places, sometimes a very engaged and voluble audience, and other times very quiet ones. He is not “entirely sure” he has cracked the text himself, and smiles that “if Mr. Beckett came back from the dead, he might not like it.” He knows audiences may be simply confused by Beckett and what is in front of them, and he and Thompson have worked hard to make their central relationship as watchable and intriguing as possible for the audience, “so there’s an emotional connection for them to watch for 85 minutes.”

He holds the last line of Archibald MacLeish’s poem “Ars Poetica” in mind when crafting his performance, “A poem should not mean/But be.”

“Part of what I feel about Endgame is that I don’t know what it means. I can’t tell you how it relates to the present ecological crisis. You, the audience, see what you see. All John, Joe and Patrice and I can do is serve this object up and hope you find it interesting for 85 minutes.”

Bill Irwin stars as Bob, Sally Field as Marilyn, Ben Aldridge as Kit Cowan and Jim Parsons as Michael Ausiello in director Michael Showalter’s Spoiler Alert.

Away from stage and screen, Irwin’s wife, Martha Roth, is an actor who has been a midwife for the last 25 years. Irwin said she was presently transitioning to a new professional role of helping those approaching the ends of their lives. Their adopted son, Santos Patrick Morales Irwin, is 32.

Next, Irwin said he would like to perform Godot again, this time playing Potso, “as a way to examine servitude and how we live with it today.” Irwin would also like to perform Molière’s The Imaginary Invalid. He “wouldn’t say no” to playing a great like Shakespeare’s Lear (he’s played that play’s Fool before), but finds Beckett “stays in my head easier” than the Bard. Keeping his fingers crossed for the necessary funding, he hopes he can take On Beckett to the Belfast Festival (and beyond to whichever theaters would like to host it), and is writing scripts for parts and projects he would like to perform himself.

It did not sound likely, or in any way imminent, but this reporter asked if Irwin would ever contemplate retirement. “Not right now,” he said firmly, smiling his wry, playful smile. “But I don’t want to die literally on stage. That can be kind of hard on an audience.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.