How Bill Richardson, political insider, found his most important role outside politics

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was late winter in Santa Fe, and former New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson had spent a long morning on conference calls in his office – part of high-stakes efforts to help free Americans unjustly detained in Russia, Iran and China.

By midday, he was ready for a break at his regular lunch joint. He walked in – greeted with “Hey Guv!” – and sat at a barstool. Over a tamale, he traded jokes and trivia with friends. Though he hadn’t been governor in a decade, and his private work was now focused overseas, one man approached him for help with an immigration problem. Richardson listened, then leaned in, asking, “What do we need to do?”

Richardson, who died Friday, had a mix of powerful connections and down-to-earth affability that was on constant display, especially in hostage diplomacy, the accidental vocation that came to define his life.

His political career, though standout, had been traditional – Congress, the cabinet, a governorship, and a run for president. Yet he grew into one of the country’s highest-profile private players working to free Americans imprisoned abroad, a job that was distinguished by being outside the government, rather than inside it.

That work, with its highs, lows and controversies, eventually dominated Richardson's professional identity.

I spent much of two days with Richardson in February for a story a colleague and I wrote about his work as so-called “fringe diplomat.” It was among the last in-depth interviews he would give in his adopted home.

Whether he was on an international phone call or trying to stump a friend at lunch over music trivia, that mix of connections and compassion was on constant display.

“He’d meet with anyone, fly anywhere, do whatever it took,” President Joe Biden said in a statement mourning Richardson’s death Saturday.

Biden noted that despite Richardson’s many high-profile offices, “perhaps his most lasting legacy will be the work Bill did to free Americans held in some of the most dangerous places on Earth.”

That assessment might have sat just fine with Richardson, a man who once aspired to be president himself.

In our interviews earlier this year, he said that helping bring families’ loved ones home had become a driving passion even before starting Richardson Center for Global Engagement in 2011.

Walking back to his office after lunch that February day, Richardson said he had had no plans to retire.

“I have no interest in doing anything but this,” he said.

Special report: 'Undersecretary for thugs': Bill Richardson's endless push to free Americans detained abroad

A career as a negotiator begins by accident

That passion began by accident in 1994, when he was on a Congressional trip to North Korea. A U.S. Army helicopter was shot down after veering into the demilitarized zone, carrying two Americans, one who died. Richardson was asked to stay until they could both be brought home – a tense negotiation he finally won.

Similar exploits over the next two years and beyond built his reputation as a go-to negotiator for wresting U.S. prisoners from dictators, terrorists and regimes hostile to the United States, from Fidel Castro to Saddam Hussein.

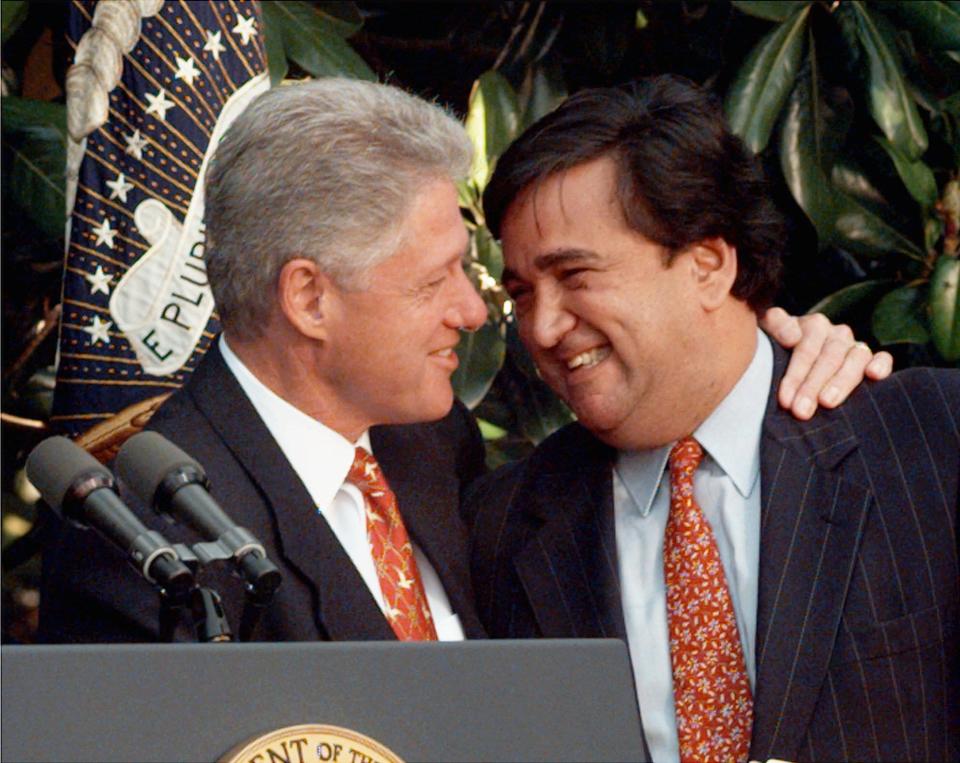

President Clinton helped etch that role into the historical record when he named Richardson Ambassador to the United Nations. In a Rose Garden announcement, Clinton regaled the crowd by noting Richardson had just returned from a rebel chieftain's hut in Sudan.

“President Clinton used to say Bill knew all the thugs,” Richardson’s wife, Barbara, told USA TODAY earlier this year. “He had a knack for it. And I think he liked the adventure of it. And it just sort of grew from there.”

Even while serving as New Mexico’s governor, he pursued the work, including flying to Sudan in 2006 to bring back Paul Salopek, a Chicago Tribune reporter.

Those who worked with Richardson said his past connections to the U.S. government, the global contacts he made over the years, allowed him to get meetings with foreign leaders or intermediaries. He might directly negotiate. And while he didn’t have the authority to set up a prisoner swap, he knew the right people to encourage both countries to agree on a deal.

He described the job of the people at the Richardson Center as being “catalysts.”

“We push to accelerate the decision-making in our own government with the other country in order to bring these detainees home,” he said this year.

Those efforts at times created tensions with the U.S. State Department. He was, at times, criticized for complicating existing government efforts to free prisoners.

“I think it probably bothers him a little bit. But I don't think it bothers him to the extent that he's not going to do something,” his wife Barbara said.

Richardson downplayed those concerns, saying he didn’t care about credit. He only wanted to bring Americans home to their families.

Freeing Brittney Griner, many others

In the last few years, Richardson was involved in high-profile cases such as the prisoner swap that released basketball star Brittany Griner from Russia. And his center also worked with more obscure cases, such as a veteran held on criminal charges in Mexico.

His work built a resume of big name cases. That included the American journalist Danny Fenster who had been imprisoned in Myanmar; Otto Warmbier, the Ohio college student arrested in North Korea who had become comatose during captivity, died soon after Richardson aided in his return; and Taylor Dudley, a 35-year-old Michigan man imprisoned by Russia after apparently wandering into the country while backpacking. In some cases, his role remained murky.

Just last month, Richardson was again nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts freeing hostages and other wrongly detained Americans.

“Whether in an official or unofficial capacity, he was a masterful and persistent negotiator who helped make our world more secure and won the release of many individuals held unjustly abroad,” President Bill and Hillary Clinton said in a statement on Saturday. “His legacy will endure with all the people who are better off today because of his outstanding service.”

A lifetime leads to a calling

Richardson said that he had originally wanted to play baseball. But eventually he decided that in diplomacy and politics he could make a difference. And he did, President Joe Biden said.

“Perhaps his most lasting legacy will be the work Bill did to free Americans held in some of the most dangerous places on Earth,” Biden said in a statement on Saturday. “American pilots captured by North Korea, American workers held by Saddam Hussein, Red Cross workers imprisoned by Sudanese rebels – these are just some of the dozens of people that Bill helped bring home.”

Richardson’s wife Barbara also knew he would jump on a plane at a moment’s notice.

Richardson was born in California – in his autobiography, he wrote that his mother had crossed the border to guarantee his American citizenship. He grew up in Mexico City as the son of a U.S. Citibank executive.

Barbara said she met Bill Richardson when she was living across the street from the Massachusetts boarding school he attended as a teen. The two were married for five decades.

Barbara told USA Today her husband’s work could be stressful but required patience. “You’re never sure what the key is that will open the door,” she said.

“I don't think people begin to appreciate how much effort it takes to get somebody out,” she said. “Rescues take a lot of planning and a lot of time, a lot of legwork and groundwork. And they involve trips that don't necessarily produce anything right away. So you have to look at the long view with the hopes of getting somebody out.”

That often weighed on him, Richardson made clear in conversations earlier this year: knowing prisoners were languishing in places like Iran or Russia, and he wasn’t able to get them out.

The Richardsons often spent three months a year at their summer home in Chatham, Massachusetts, which is where he died in his sleep Friday.

The rest of the year they lived in Santa Fe, where he unwound after high-stakes trips. He drove a yellow Jeep Wrangler he’d owned for a decade to an office carpeted with the New Mexico state seal, a reminder of his years at the state capitol a short distance away.

His staff still called him “the Governor.”

Richardson said he was glad of some hopeful trends. Families of hostages and the wrongly detained had become better informed and more active in recent years – and better at pressing for attention, after years of tensions around that question. Past hostage families had sometimes stayed silent for fear of upsetting delicate negotiations.

“I always say go public. The government says no, don’t, because then you raise the stakes,” Richardson said in February. “It's better to have the press and pundits and Congress advocating for you.”

Richardson said he had seen the government give the issue more coordinated attention over the years.

But his death comes as wrongful detentions are a growing problem, highlighted recently by Russia’s arrest of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich on espionage charges the U.S. says are false.

Richardson said that he hoped the center would continue its work if he did ever retire. The center’s director, Michael “Mickey” Bergman, a former Israeli Defense Forces member who directs the center's work, has not yet commented on who will run it next.

While Richardson Center isn’t the only private groups or people working to free Americans, it had long been among the most open about it, Richardson said in between calls in his office in February.

“I hope there are more,” Richardson said, “because I think they're needed.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Bill Richardson: How New Mexico governor found most important calling