Biodiesel wastewater proposal draws skepticism in Pondera County

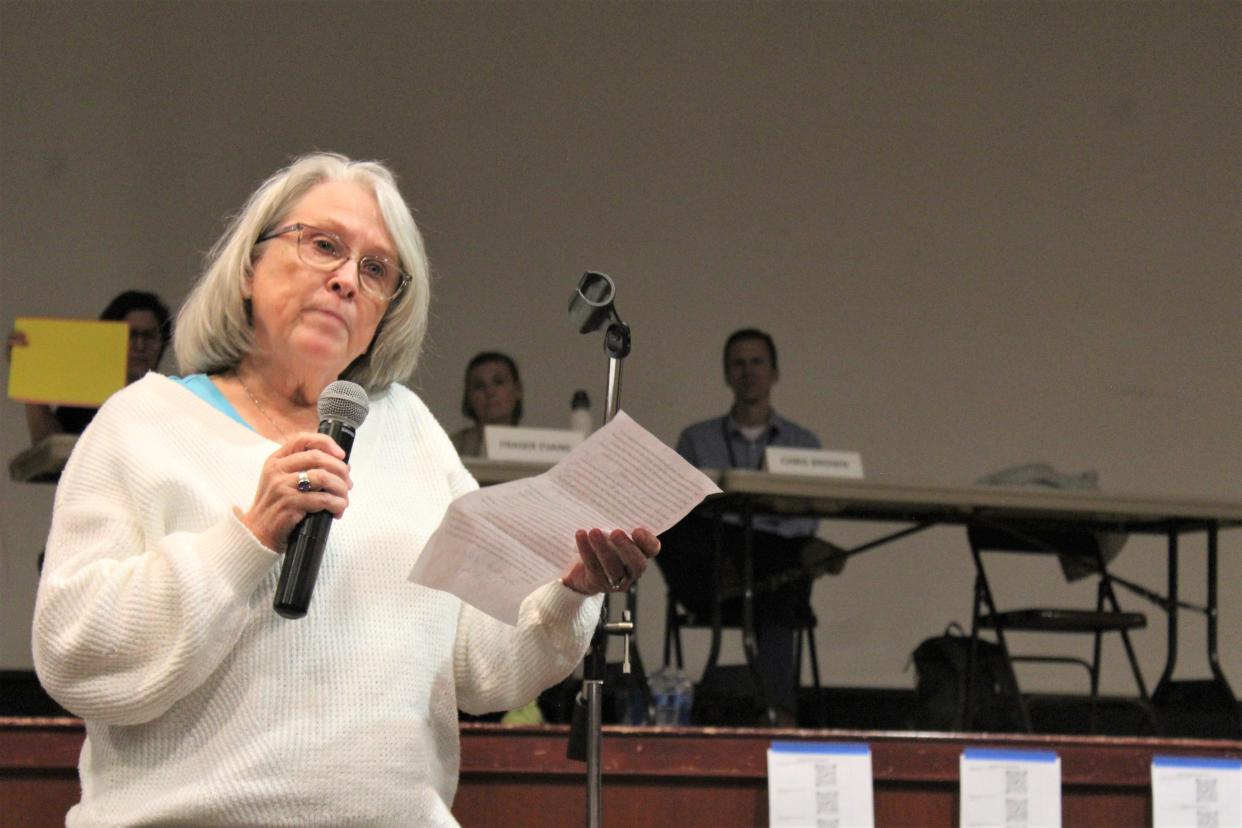

Close to 100 people attended a meeting in the Conrad High School auditorium last Wednesday, where Environmental Protection Agency officials took comments and attempted to ease citizen concerns about two old oil and gas wells which could be used to contain as much as 14 million barrels of wastewater from the Montana Renewables plant in Great Falls.

Montana Renewables was formed in 2021 as a subsidiary of Calumet Specialty Products. It has since become the largest producer of bio-fuels in North America, using base ingredients like oils from crops such as camolina, hemp and canola combined with animal fats and even recycled cooking grease to produce low-emission bio-diesel and aviation fuel.

While the prospect of producing millions gallons of sustainable and biodegradable fuels from agricultural products grown and raised locally is optimistic, the process to create then requires large amounts of water to wash and remove the chemicals, salts, and other minerals the “feedstocks” have picked up along the way. Montana Renewables’ plant in Great Falls produces roughly 2,500 barrels (105,000 gallons) of wastewater a day.

While this wastewater is not classified by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as “hazardous,” its disposal does have to meet minimum federal standards dictated under the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act. That’s presented a problem for Montana Renewables since Great Falls’ water treatment plant is ill-equipped to take in and treat the additional volume of wastewater Montana Renewables is producing.

Since the beginning of 2023 Montana Renewables has been paying a trucking company to haul its wastewater to Shelby, where it has been loaded on train cars for disposal at industrial injection wells in Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. It’s been an expensive prospect.

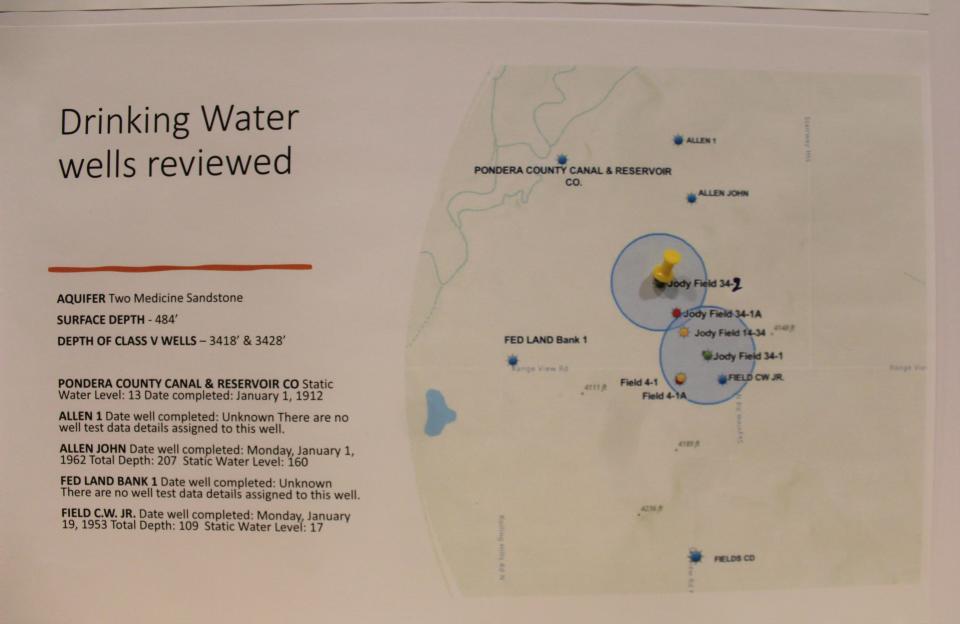

Beginning in 2021 Montana Renewables began negotiations with Montalban Oil and Gas Operations (MOGO) to inject up to 13½-million barrels (570 million gallons) of biofuel wastewater into two played out oil and gas wells roughly 12 miles west of Conrad. The Jody Field wells, named for the property owner whose land the wells sit upon, had already been accepting injected oil and gas wastewater for nearly 13 years. According to EPA documents the Jody Field wells have taken in more than 500,000 barrels of contaminated water, primarily a saltwater brine infused with chemicals used to help force out oil and gas during the drilling process.

In 2022 MOGO applied to the Montana to deepen and expand the Jody Field wells, which extend beneath the Madison Formation aquifer, a major source of underground drinking water for farms and communities across central Montana. That same year the Montana Board of Oil and Gas authorized the conversion of the two Jody Smith wells into Class V wells for the storage of non-hazardous wastewater below dense limestone formations found 3,700 feet below the surface.

Those permits are conditional upon the EPA’s approval. Many of the attendees at Wednesday’s meeting were skeptical of EPA officials’ assurances that the Madison aquifer will be protected.

“What happens if the EPA’s funding is cut drastically,” asked one woman in the audience at the Cut Bank High School auditorium, “and when there were very little resources for monitoring and enforcement of these wells?”

“I’ve been with the agency for 26 years and we have seen some funding cuts,” replied VelRay Lozano, a lead project reviewer for the EPA. “Typically, what happens is a lot of the incentive programs lose their funding. Drinking water protection has always been something that has not been cut much. Usually, enforcement stays pretty well on top of that. We try and implement the Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act as fully as possible. Water is usually not something that is pulled back on, and the regulations have been in place for a long time.”

“Has there been any testing done to show that the wells didn’t leak any chemicals into the surrounding water? Monitoring of the surrounding water to see if there’s already been a problem before seven million to 14-million barrels is added, which would theoretically flush it all out into the Madison Aquifer?” asked a woman from the audience who said she lived about four miles away from one of the proposed injection wells.

“What I’m asking is has there been any testing to make sure that these wells did not leak anything that they already contained before there is another large quantity of wastewater and possible toxins added with a big flush?” she added. “It seems to me that adding that quantity of water and giving it a flush isn’t going to make it stay put. There’s a big consequence if it doesn’t.”

Senior EPA environmental supervisor Chris Brown could not answer the specific question of whether there had been any prior leakage at the Jody Smith wells but said there is a continuous monitoring program for injection wells across the state.

“The Montana Board of Oil and Gas has the primary enforcement authority for Class II wells,” responded Chris Brown, a senior environmental supervisor for the EPA. “Class II wells do have requirements for monitoring. There are long-term testing requirements, it’s just under a different jurisdiction. There are state oversight state programs. They come in a number of forms. There’s reporting that happens, there’s mid-year reviews. There is interaction with the state after it has received primacy.”

“If you’re talking about putting a monitoring well all the way down into the aquifer where these injection wells are, that would be popping another hole into the ground that could then cause leakages,” Lozano commented.

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: Proposal to store biodiesel wastewate near Conrad draws skepticism