The untold story of how a robot army waged war on COVID-19.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In an old bank building in Brooklyn, N.Y., amateur microbiologists were tinkering with DNA when the anarchist appeared. Then came a robotics expert, coders and other industry revolutionaries. Before long, this collection of inventive, if wildly independent, experimenters would reimagine COVID-19 testing in the fight against a globe-crippling pandemic.

That moment in the spring of 2020 was emblematic of how disrupters upend the status quo to advance science and technology. Will Canine, a biohacker and former Occupy Wall Street organizer, and his team of idealists and iconoclasts launched a Kickstarter campaign to build a robot that they hoped would bypass elite labs and corporate monopolies to change the world. They succeeded.

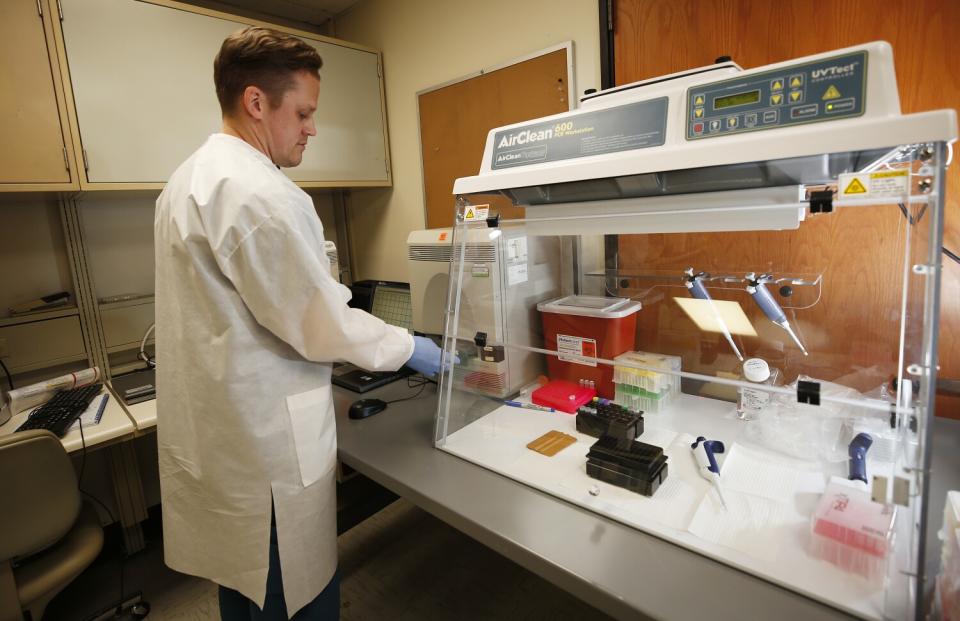

The federal government and corporations such as LabCorp had failed to scale up COVID-19 testing, which often involved a tedious liquid transfer process called pipetting. Canine and his fellow biohackers developed an automated robot platform to speed things along. The platforms have since been shipped to more than 40 countries with dramatic results: In New York City, for example, the turnaround time for test results went down to 12 hours from two weeks, helping to quickly isolate infectious people and reduce the virus’ reach.

Without the robots, the pandemic probably would have killed thousands more in its early days. The platforms are now detecting and tracking new coronavirus variants and helping test for dozens of other infections, including HIV and the flu. Few people have even heard of Opentrons. But the company — valued a year ago at $90 million — is now worth $1.8 billion.

The story of Canine's low-cost robot, called OT-2, is part of a broader movement by amateur scientists to democratize biotechnology in order to avert or correct catastrophic failures by the establishment.

Public access to biotech tools is accelerating at a pace that makes the software revolution of the late 20th century seem archaic. It presents monumental ethical challenges and makes law enforcement officials anxious over security threats. But COVID-19 has altered the political landscape of biotech, exposing both the failures of a traditional diagnostic bureaucracy and the little-known army that came to its rescue using the lifesaving potential of open-source science.

Megan Palmer, a biological engineer at Stanford who studies the intersection of security and biotech, called it "a moral imperative — a moment of pivotal, global reflection where we decide: Are we going to build platforms to let everyone innovate?"

* * *

Long before the robot, the microbiologists signed a lease in Brooklyn.

In 2013, every tenant at 33 Flatbush Ave. — the converted bank — appeared to be a hacker at heart: foam sculptors, biofuel-inspired costume designers and a tech-artist group called Dark Matter Manufacturing. The buzzer of the building had been rewired to blast native birdcalls; sidewalk passersby often glanced over their shoulders as a bald eagle clucked.

In the penthouse, the lab, called Genspace, had a leaky roof and no air conditioning or heat. But it was better than the living room where the microbiologists had met before. Every inch of the lab overflowed with computers, plants and projects. Concerned that such hacker spaces can attract unwanted attention, one of the founders, Daniel Grushkin, announced safety guidelines and reached out to the FBI to dispel any rumors the group was dangerous.

Biohackers — homegrown geneticists who manipulate the code of life — had been mischaracterized for decades. They fell under increasing scrutiny after a string of biological incidents in the spring of 1995: a Japanese cult launched a deadly sarin attack in the Tokyo subway system; the Oklahoma City bomber killed 168 people using little more than corn fertilizer, the explosive Tovex and drag-racing fuel; a neo-Nazi sympathizer, Larry Wayne Harris, stored three vials of a plague-causing bacteria in the glove compartment of his Subaru.

Fears over such attacks and other threats multiplied. After the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, about a decade before Genspace moved into the bank — a time when Canine was a troublemaking eighth-grader reading comic books in the heart of Silicon Valley — law enforcement was responding to anthrax mailings and bracing the nation for a new era of terrorism.

***

FBI Special Agent Ed You had a particular interest in biological threats.

“Most weapons of mass destruction require very specific materials and knowledge; they’re pretty well-tracked and well-regulated,” said You, a former cancer researcher at Amgen. “But biology is the opposite: The tools are naturally available. It’s open-source by definition.”

Just as collaborative community labs proliferated in old bottle-cap factories and cellars, so did the number of Americans plotting deadly attacks with chemicals blended in their bathtubs. To a layperson, sinister concoctions and those meant to do good were indistinguishable.

In 2005, after dozens of FBI agents in hazmat suits had raided the home of a harmless bioartist — confiscating computers and petri dishes of nondangerous specimens — You realized how far behind the agency was at understanding legitimate biothreats. He swapped his lab coat for a badge, joining a field office’s terrorism task force and then the Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate.

His goal was to develop inroads with do-it-yourself biologists, such as the ones who formed Genspace, to encourage innovation and prevent disaster. He became the agency’s biohacking insider, courting the amateurs clanking beers at local lab parties and building a Rolodex of contacts. He was hard to miss: bald, animated and often in his ascot cap.

You entered a world of colorful, if often suspicious, pioneers that included the likes of Aaron Traywick, who injected himself with a homemade herpes treatment in front of a live audience. You met Thomas Landrain, a Parisian with thick curls and a beard who'd designed biosensors, or microscopic eyes and ears planted onto bacteria; once engineered, those organisms could alert militaries to unseen dangers in thick woodlands or the Pacific.

He knew of the biohacker in Germany who used dog saliva on tennis balls to discern which neighbor was allowing a pet to poop on his front lawn, and a breeder who used human sperm to test out gene-editing ideas before introducing them to puppies. There were still more: biohackers trying to cure cancer, create home-brewed insulin, implant chips under their own skin.

You discovered that most biohackers live by the software revolution's concept of the Cathedral and the Bazaar: the notion that, when knowledge and power are concentrated, society sees great losses in efficiency. Their approach is to propel grass-roots innovation to tear down the cathedrals and convert them into open-source bazaars.

“DIY-Bio actually started educating the FBI, telling them how people could modify yeast to make opioid precursors. It was Breaking Bad to Brewing Bad,” You said. “I knew we were going to need these guys.”

* * *

Canine was looking to experiment. He wanted to extract and read DNA from his inside cheek, but his unsteady hand kept bungling the pipetting process at Genspace. That's when the robot idea struck him.

He had no background in molecular biology, but his ties to Occupy Wall Street — he'd twice gone to jail for his protesting — convinced him that DIY-bio was part of a larger movement hedging against a capitalist takeover. It infuriated him that only the most elite labs used automated machines often designed decades ago that could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. And as a student of artistic engineering, Canine, who had experience with 3-D printers, imagined a better way.

"I could download a unicorn head and print it out — so why couldn't I download and print this experiment?" he asked.

“Biotechnology is how we heal ourselves. It’s the most important technology, yet the least accessible," he added. "I wanted to give people tools to have a new type of power."

Canine partnered with a couple of techies from a DIY-Bio listserv — Chiu Chau and Nicholas Wagner, who had already built a first model of Canine's robot idea. The two recruited software gurus to design a robot interface that let lab technicians choose various ingredients and commands. Once materials were loaded, tiny syringes called micropipettes plunged into wells in unison and transported fluids thousands of times. Canine's company, Opentrons, was born.

Community biologists could now quicken and expand their lab work and share protocols around the world. That, to Canine, was power. And to biohackers everywhere, it was a perfect bazaar.

In 2014, the Opentrons invention was accepted into Haxlr8r, a summer-long hardware accelerator in Shenzhen, China, that turned the robot into a mass-manufacturable product. Then, on Halloween, at a microbe-engineering competition in Boston two worlds briefly crossed orbits.

Dressed in a blue sport coat, Special Agent You was mingling among thousands in the convention center. Canine was there with his new robot prototype. He was hard to miss, wearing a glow-in-the-dark skeleton costume, sneakers, a boyish haircut — and a big grin.

“He came right over, and he said, ‘Can I show you what we got?’” You recalled.

That day, Opentrons launched its Kickstarter campaign. Its success meant the robot team had to expand outside Genspace. Its members migrated down to the fourth floor at 33 Flatbush, beside a Marxist journal’s headquarters, the windowless suites stacked floor to ceiling with socialist theory books and mechanical arms.

After getting into Y Combinator — a seed accelerator used to launch startups such as Airbnb and DoorDash — Opentrons brought on Jonathan Brennan-Badal as its new chief executive. Brennan-Badal had helped ComiXology, a digital comic book platform, outpace Apple and Amazon. He’d transformed one industry and wanted to do it again.

As Opentrons published papers and coded robots, seeking the right market fit, none of its biohackers knew a disaster of graphic novel proportions was about to unfold.

* * *

The American healthcare system was in free fall in February 2020. The novel coronavirus was rippling across the nation, and the only way to slow transmission was to detect cases. But budgets had been gutted. Government testing criteria were too narrow. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's assay fell flat. At the pinnacle of all the federal agencies, President Trump simply proposed a biohacking solution of his own: Try injecting yourself with Clorox.

Traditional companies such as LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics vowed to test and isolate coronavirus patients across the country. But their supply chains buckled, and with them any hope of delivering test results while they were still relevant. By late March, more than 150,000 samples had piled up at Quest unprocessed — about half of the total number the company had received.

The fragmented and siloed world of laboratory science became the crux of the crisis; the fate of millions rested upon hand pipettes and fax machines. But when the Food and Drug Administration issued emergency use authorizations to allow more competition, the regulatory barriers once faced by Opentrons evaporated overnight. The company shipped hundreds of OT-2 robots to U.S. cities and beyond. They were deployed to pop-up labs built in shipping containers in London. At one hospital in Spain, grateful lab technicians named each robot after a loved one lost to COVID-19: Joan. Javier. Paco.

* * *

Today, behind the scenes of America’s COVID-19 testing infrastructure, OT-2 robots are helping screen millions for the virus: elementary school students, nursing home residents, patients headed in for surgery. The tests often cost as little as a dollar per person, resulting in savings of $150 million.

Customers include the Mayo Clinic, Harvard, Stanford, Caltech, MIT and even BioNTech, the German company that developed a COVID-19 vaccine with Pfizer. More than 2,000 scientists from across the world are now plugged into Opentrons hardware-software ecosystem. Its largest impact has been in New York City, where a 5,000-square-foot facility can handle up to 50,000 patient samples per day.

"A lab is an orchestra of machines,” said Julian Moncada, the company’s head of strategy and innovation, who works among a staff of 120 scurrying in blue coats and gloves along an around-the-clock assembly line. “But the software is the conductor.”

Since January 2021, OpenTrons has sequenced 25,000 genomes from positive coronavirus test samples in New York, helping scientists detect new variants: in February, the Beta variant; in April, the Delta variant; in June, the Delta-plus — a virus with a blend of mutations first detected in India and South Africa.

Opentrons — which has grown to more than 500 employees — wasn’t the only biohacking firm to mobilize against COVID-19. A generation of disrupters has emerged from the shadows. When a respirator company depleted its inventory but refused to share its design, startup engineers built them out of snorkeling masks and 3-D-printed valves. Maker's Asylum, a hackerspace in India, recruited volunteers with laser cutters in 42 cities to produce more than a million face shields.

You, the FBI agent, is not surprised. He recently finished a national security detail to the Department of Health and Human Services for the pandemic response and is back doing the work he loves most: hanging with hackers. He's focusing on the convergence of cyber and biohacking threats, including those coming from foreign governments to undermine health systems and upset the battle against COVID-19.

"Whether you're part of a major lab workflow in the U.S., like Opentrons, or you're working on code in your home lab, there are brand-new vulnerabilities — a lot at stake," he said. "Wouldn't it have been nice if someone like me had met with Steve Jobs back in the beginning?"

Everyone is the looking for the next breakthrough innovation. Genspace, the dynamic community founded in the Brooklyn bank building, has moved to a palatial space in Sunset Park. It is hosting in-person classes for biotech denizens with big imaginations: genome editing, kombucha papermaking, painting with microbes.

This weekend, it's offering a biohacker boot camp, pipetting and all.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.