At the Bionic Olympics, Engineers and Athletes Make Miracles

The day of the finals in the powered exoskeleton race at Cybathlon 2016 opened on a less-than-promising note.

Mark Daniel, a 26-year-old former welder who’d been paralyzed from the waist down in a car accident at 18, was rushing down a ramp at the venue when his wheelchair caught on a post. He took a hard tumble out of his chair and onto the pavement. This alarmed his teammates, a group of six engineers and technicians from the Florida Institute for Human & Machine Cognition. They’d been working 12-hour days for months, designing, assembling, and refining the robotic exoskeleton suit for which Daniel served as the lone pilot. They had no Plan B. Given the public and media spotlight focused on Cybathlon, careers could rise or fall depending on Daniel’s performance.

All week in Zurich, Switzerland, it had been Go slow, Mark. Take it easy, Mark. He understood the concern, but Daniel was determined to make the most of his first trip abroad. Before this, the Floridian hadn’t done much traveling beyond Tallahassee.

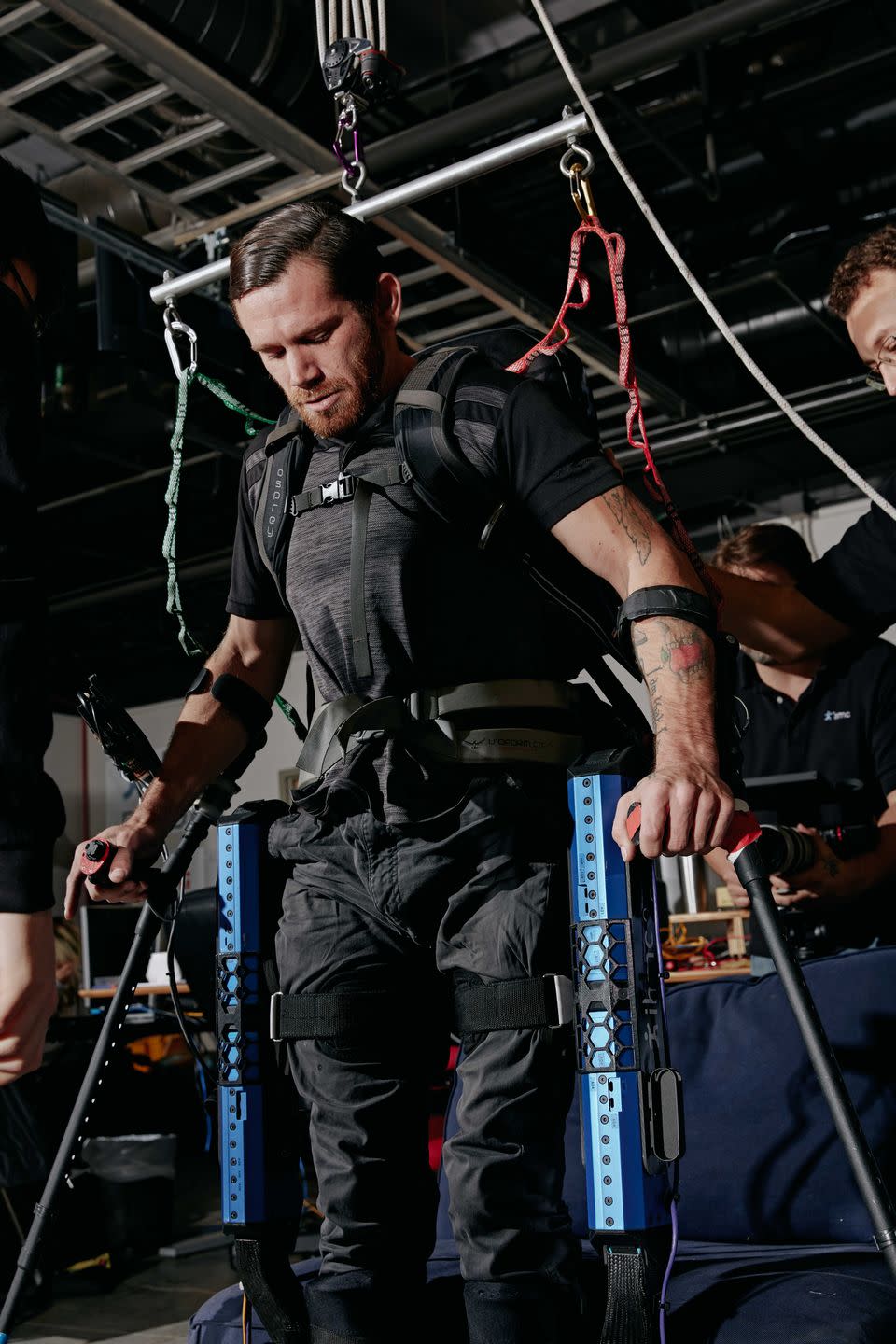

On their first night in town, before anybody went to bed, Daniel’s teammates had unpacked and assembled the exoskeleton—70-plus pounds of aluminum-alloy frame, compact DC motors, sophisticated software, and lithium battery powered actuators. Daniel donned the suit, and the engineers asked him to walk down the hallway to test it. Instead, he made a beeline for the elevator, rode down to the lobby, and high-stepped through the bar. The next day, in his wheelchair, Daniel rolled out to see the city.

Now, after the tumble at the venue, team members fluttered around him nervously, but he was fine, he was okay, and now it was time. Daniel was in the arena, lining up for the final. The 6-challenge, 40-meter-long courses were laid out in adjacent paths, allowing spectators to follow the action. His opponent was a man from Germany piloting a commercially made exoskeleton he’d used for years; Daniel had trained on the IHMC device for just eight weeks.

Organized and hosted by ETH Zürich, an elite Swiss science and technology university, Cybathlon showcases individuals with significant physical disabilities competing in races that simulate everyday tasks. It shines a spotlight on the high-tech prosthetic devices designed by the world’s leading research groups that enable them to compete.

Each event presents a fascinating dance between human and machine: the energy of the cyclists blasting around the track in the functional electrical stimulation event; the intricate play of contestants buttering slices of bread in the powered arm prosthesis competition; the bull-rush charge of the powered wheelchair race.

But the powered exoskeleton race, a combined athletic and engineering spectacle in which people who are paralyzed are empowered to walk, recalls the Biblical miracle at the pool of Bethesda. Strapped into his suit, Daniel stood for what was arguably Cybathlon’s marquee event.

He clicked the button on the control panel of his right crutch, which sent a walk command through the software in the computer in his exoskeleton’s backpack to motors housed in the actuators encasing his leg joints. Daniel stepped to the start line. He knew that he carried a flag not just for his teammates, but for a burgeoning community of the disabled: In the U.S. alone, an estimated 291,000 people are living with spinal-cord injuries. Instead of causing him to freeze up, the pressure broke something open.

“Suddenly, I felt crystal clear inside my head,” he says. “The stands, the fans hollering, the guy in the exo next to me—I didn’t see or hear any of that. I was in a bubble. All I saw was the lane in front of me.”

It’s November 2019, and engineers at the IHMC robotics lab in Pensacola are gearing up for their second shot at the powered exoskeleton race when the Cybathlon returns to Zurich, currently scheduled for September 2020.

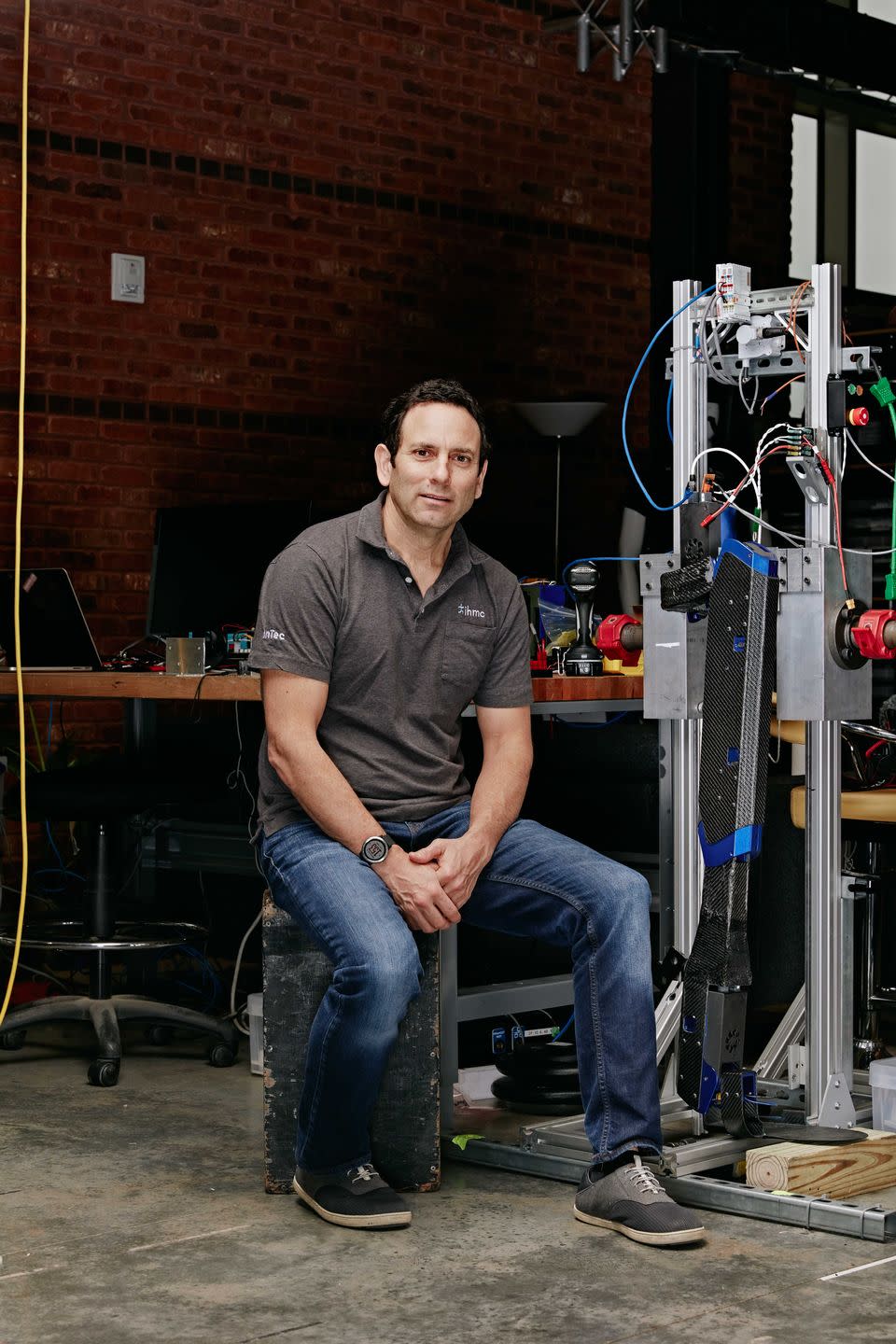

Their new, upgraded exoskeleton (dubbed “Quix”), is beginning to come together. At the daily 9:30 a.m. staff meeting, Cybathlon team leader and senior scientist Peter Neuhaus has his game face on.

A video of the exo race at Cybathlon 2016 plays in a loop on the lab’s overhead monitors. It shows Mark Daniel maneuvering the suit gingerly as he ascends and descends a ramp, opens and closes a door, and negotiates a slalom line. Daniel will return as the team’s pilot at Cybathlon 2020.

Serving as a template for the 2020 exoskeleton, the suit Daniel wore at the 2016 event (called “Mina v2”) sits in the middle of the lab, perched jauntily on an IKEA sofa. With its 6-foot-tall humanoid shape, articulated hip, knee, and ankle joints, and mechanical “feet” set flush on the floor, the device looks like it’s about to stand and walk on its own; a feat that, with a few tweaks, lies well within its power. Lead software and controls engineer and Cybathlon team member Brandon Peterson explains that the software and mechanics in the exo are similar to what’s used in IHMC’s humanoid robots.

“Mark directs the exoskeleton, but he’s actually sort of riding the device,” Peterson says. “The exo weighs about 75 pounds, but the user doesn’t feel like they’re carrying that extra weight. Like a car or motorcycle, the exo is grounded and supports its own weight. Mark is along for the ride, but still relies on his crutches for balance.”

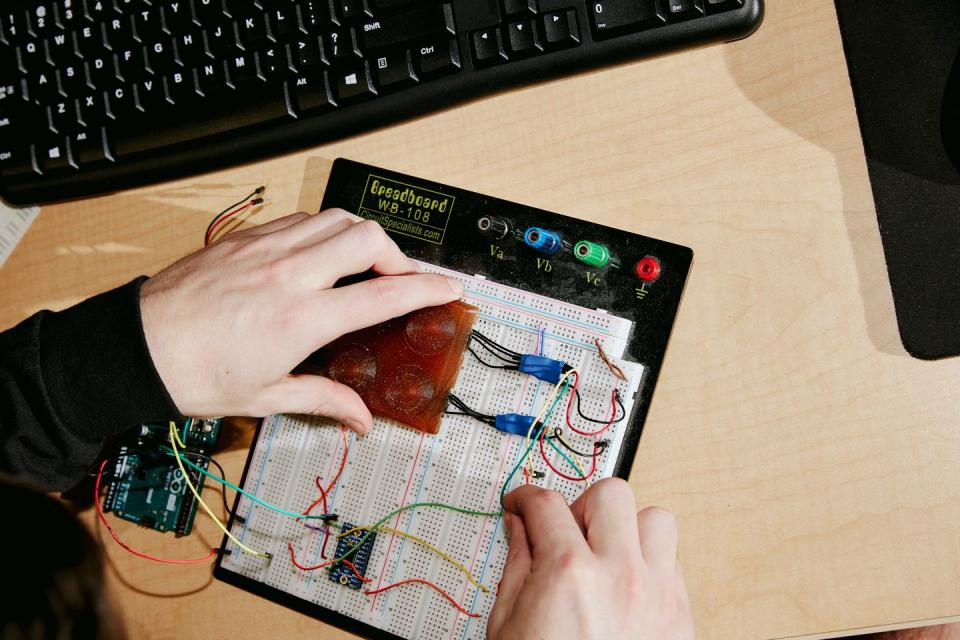

Peterson is designing one of the key upgrades for the suit that Daniel will wear for the 2020 competition: sensors embedded in the soles of the exo’s feet that send pressure data to the computer housed in the suit’s backpack. The computer then transmits vibrations to pads in Daniel’s vest, alerting him if he’s off-balance and ensuring that he’s in a safe position to take another step. “Able-bodied people do that naturally, using proprioception in the lower body to gain an understanding of their joint positions without having to look down at their legs,” Peterson says. “Mark can’t do that. He has no sensory feedback in his legs, and the messages to and from his brain stop at the break in his spinal cord.”

There will be other updates as well: The team has added two actuators to the exo that will allow Daniel to move laterally without having to pivot the entire suit. They’ve also shifted the transmission system in the DC motors from a harmonic drive, whose high gear ratio produces higher friction, to a ball-screw linkage system that reduces friction. New copper tubing will drain heat from the actuators. The challenge is to make everything as cool, small, lightweight, and user-friendly as possible.

Peterson pauses, running his hand along the blue aluminum-anodyne actuator machined to match the length of Daniel’s right thigh. “Programming balance in an autonomous humanoid robot is relatively easy,” he says. “Achieving autonomous balance control on a device to which a human attached is another story. When off-balance, the exo will make a correction based on the software algorithm and the user will instinctively correct with their crutches. The two actions can end up fighting each other, resulting in a dangerous tug-of-war between the robot and user.”

So having a human being in an exoskeleton makes the job of balancing a lot harder. But of course, the human being is the whole point.

Mark Daniel was five years old when he started riding dirt bikes through the pine woods around Pensacola. He was 15 when his mom and dad insisted he quit after a crash ruptured his spleen and nearly killed him. Daniel redirected his restless energy and hunger for adrenaline into cocaine and small-scale street crime. He was 17 when his parents confronted him with a choice: continue on a path of self-destruction or deal with his addiction by enrolling in the Job Corps. Daniel picked Job Corps.

He arrived at the Muhlenberg Job Corps Center in Greenville, Kentucky strung out, weighing 130 pounds, and not far from death. He sweated out the drug cravings, got certified in diesel maintenance, and learned to weld. He ran 10 miles a day (5 in the morning and 5 at night), ate upwards of 6,000 daily calories, lifted weights, and put on 40 pounds of muscle. Nine months later, a new man, Daniel returned home to Pensacola and dived into work.

Then came October 19, 2007. A Friday night. Daniel had been working seven days a week, 10 to 14 hours a day, making good money with no time to spend it. He was just 18, but a plan was taking shape. Work for 10 years, keep saving money. Buy a place in the country with space for his tools, vehicles, and maybe a few animals. Pay cash. No mortgage. Daniel envisioned starting his own contracting company and becoming his own boss.

That Friday night, he clocked off the job—steel fabrication for a new U.S. Navy storage facility—around 7:30, after working 93 hours in eight days. On the way home he stopped by a friend’s house to relax.

“Now here I am, Friday night at Ayo’s place,” Daniel recalls. “Before I know it, I’m dead asleep.”

Two hours later, he awoke with a jolt. Ayo urged him to go back to sleep, spend the night on the couch, but Daniel was riding that work wheel—the iron adherence to routine so crucial for people in recovery. He decided to make the 20-mile trip home to sleep in his own bed.

Daniel drove on a dark two-lane road in a rural stretch of Escambia County. He nodded off and brushed a guard rail on a bridge crossing the Escambia River. “I cranked up the radio and reminded myself that home was less than 10 miles away,” he says. “That’s the last thing I remember.”

Hours later he woke up in the ICU paralyzed from the waist down. “My spinal cord was broken and one lung crushed from being smashed against the center console of my truck as it flipped seven times,” he says. “Doc tells me I coded once in the medevac helicopter and again on the operating table, and made it clear that the only reason I survived was because I was so strong and fit.”

After 28 days in the hospital, Daniel moved back into his mother’s house. “One day I’m laying in bed feeling sorry for myself when my mom comes into the room. She sits down and says, ‘Son, I’ll always support you. But I’m going to die a long time before you do. So unless you plan on laying in bed the rest of your life, you best get to work.’”

Daniel went to work. “Rehab city for a solid year,” he says. “I accepted my situation, and decided that the wheelchair was not going to be my burden. I was going to be a burden to the chair.”

He soon recognized that a paraplegic’s life is defined by transitions: in and out of bed, in and out of a car, back and forth to the bathroom. Building on his active childhood and the exacting physical training he’d done in Job Corps, Daniel forged himself into a master of transitions. He learned to slip in and out of his wheelchair with ease. A few years after his accident, Daniel logged time driving for Uber and Lyft in the Pensacola area. Only a handful of passengers suspected he was disabled at all.

“You have to be willing to push it and take chances,” Daniel says. “Dirt bikes taught me countless lessons growing up. One being that if you’re not sure how a situation is going to turn out, you go full throttle to find out as quick as possible. That’s how I decided to live in this wheelchair, full throttle. ”

One day, about a year after his accident, Daniel received a phone call from his physical therapist at West Florida Rehabilitation Institute. There was a man from IHMC who wanted to talk to him, she said.

“I lived my whole life in Pensacola but never heard of any IHMC,” Daniel says. The physical therapist briefly explained who they were. “I said sure, I’ll come in and talk to the man,” Daniel says. “That’s how I met Peter.”

Peter Neuhaus grew up in an apartment on the West Side of Manhattan, the son of two psychologists. He graduated from MIT with a degree in mechanical engineering and earned his master’s at UC-Berkeley. After a stint teaching school back in Brooklyn, he returned to Berkeley for his doctorate. His thesis advisor was the robotics pioneer Homayoon Kazerooni, Ph.D., who is a pioneer in powered exoskeletons and founded two companies that manufacture commercial exos that are approved by the FDA.

After earning that degree and working for a Silicon Valley software startup for a few years, Dr. Neuhaus and his family moved to Pensacola, where he joined the program at IHMC.

In the early 2000s, the field of wearable robotics, broadly defined as mechanical devices that enhance the physical performance of the user, experienced exponential growth in research and programs. In the U.S., the work was supported by the federal Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which liberally funded a program for “human performance augmentation,” robotic devices that would boost the strength, speed, and stamina of able-bodied military service members. Major universities, along with military contractors such as Raytheon and Lockheed Martin, pursued research for robotic devices that could be used in factories and fulfillment centers as well as on the battlefield. Internationally, automakers including Toyota, Honda, and Mitsubishi launched similar efforts.

The main challenge, engineers discovered, was power. Pneumatic and hydraulic sources produced high energy output but were prohibitively heavy, and their outputs were difficult to precisely control. Electrical batteries provided a lighter alternative but were comparatively under-powered. In a size that an individual could comfortably wear, they failed to deliver the juice required to allow soldiers to bound over apartment buildings or assembly line workers to lift thousand-pound components. For devices that could help the disabled, however, electric batteries could provide sufficient power. The field of wearable medical robotics was born, the powered exoskeleton serving as its poster child.

There were other challenges, such as transferring power between the exoskeleton and the human in it at a rate that wouldn’t rip off an arm or a leg. Actuators—compartments packed with gears, electronics, and a lithium-battery-powered motor running on DC current—performed this function.

In 2005, Kazerooni, Neuhaus’s former Berkeley advisor, founded Ekso Bionics with two partners. The company manufactured the first commercially available exoskeletons. The suits had two actuators per leg, placed outside the hip and knee joints. The legs connected to an aluminum torso structure that supported the user’s legs, back, and hips in an upright position. A computer in the backpack ran any automatic algorithms, while the user directed the suit through a control panel on one of the device’s two crutches.

The suits were expensive, costing as much as $80,000. They weren’t covered by insurance and required a steep learning curve. They weren’t as convenient as legs: They moved slowly and couldn’t be used on wet or rough terrain. The batteries failed to provide enough power for all-day personal use. But for all their problems, exoskeletons delivered a kind of miracle: A paralyzed person could walk again.

Neuhaus thought he could improve the device. Earlier in his IHMC career, he had designed a walking algorithm for DARPA that allowed a four-legged, dog-sized robot to traverse lunar landscapes. He helped develop software for a humanoid robot named Atlas that took second place in the DARPA robotic challenge, netting IHMC a $1 million award and international prestige. Now he aimed to import tech from both projects to a newer, better exoskeleton.

Because IHMC was a nonprofit committed to research and pure science, Neuhaus didn’t have to worry about building a marketable product. After a careful study of biomechanics, he developed an exoskeleton that added a third actuator on the ankle joint, which would improve toe lift-off, a key to the human gait. A prototype showed promise, but Neuhaus had difficulty finding a disabled person with the strength, coordination, and nerve to successfully pilot the suit.

“We needed a younger individual, relatively recently disabled, who hadn’t lost too much muscle tone or bone density,” he says. “We needed a person with good athletic skills who wasn’t threatened by machines and technology. Most of all, we needed someone who wasn’t afraid.”

Neuhaus asked around the Pensacola-area rehab community and eventually contacted the West Florida center. The staff physical therapist smiled when she heard Neuhaus’ request. “I’ve got just your man,” she said.

We need a volunteer to give feedback on our exoskeleton, Peter Neuhaus said, and Mark Daniel was sold. It was 2009, and Daniel was a little naïve about how quickly and easy walking again would be. “I thought I’d be walking around the block the next week,” he says. The first rig had big DC motors and very basic electronics. Daniel didn’t actually control anything. The project’s lead electrical engineer, a guy named Travis Craig, managed all the controls.

During his early years serving as the test pilot for the IHMC exoskeleton, Daniel worked on an on-call, volunteer basis. He and Neuhaus formed an odd couple: the early-middle-aged, MIT-educated native New Yorker, and the representative citizen of the grits-and-four-wheelers Florida Panhandle (affectionately called the Redneck Riviera by locals), who was barely out of his teens. But they quickly formed bonds of trust and respect.

“The first thing I appreciated about Mark was his fearlessness,” Neuhaus says. “And he had the ideal physical tools and manual skills, along with a strong work ethic. I can’t imagine a better pilot.”

The feeling was mutual. Initially, when Daniel met Neuhaus, they had a father-son type relationship. Neuhaus had 20 years on him. “I’ve grown up,” Daniel says now. “Now we’ve got more of a friendship.”

Daniel began to spend more time at the lab, helping the staff with welding and other jobs. He evolved into an unofficial spokesman for IHCM and the exoskeleton, speaking to the media and making public appearances.

More important, Daniel exhibited an innate gift for piloting the exoskeleton; an almost artistic approach to marrying human with machine.

“I feel comfortable in the suit,” Daniel says. “But it’s also a little weird—like driving a car with a slack steering wheel. There’s a lag between thinking about making a move or step and actually doing it.” In the suit, Daniel runs through the countless decisions, big and small, that make balancing in an exoskeleton such a challenge. “Meanwhile, I’m thinking ahead, watching the ground, thinking about how many steps to those stairs or that door and how am I going to position myself when I get to that point. Am I going to turn the exo three-quarters or half-way? It sounds complicated, but inside my head it’s all very seamless and automatic.

“Being in the exo doesn’t give me any superpowers,” Daniel says. “But it gives me back some of what I lost.”

Cybathlon 2016 shaped up as the ideal place to showcase—and test—the IHMC exoskeleton, along with Daniel’s ability to pilot it. Held over two days in front of a crowded arena and drawing heavy media coverage, the inaugural 2016 event attracted 66 teams from 25 nations. Combining aspects of a scientific conference, consumer electronics show, and an indoor track meet, Cybathlon functioned as a rendezvous for the world’s leading robotics research groups.

There was a brain-computer interface competition in which pilots controlled a character in a virtual running race. The pilots, all of whom had complete or severe loss of motor function from the neck down, jockeyed devices that enabled them to guide an avatar using specific patterns of brain activation. An incorrect brain signal slowed the avatar-runner. If the computer received the proper brain signal, the avatar booked.

In the exo race, pilots faced six tasks in 10 minutes, all of them mimicking real life movements. They were required to stand from a sitting position on a sofa; to walk up and down a tilted ramp; to walk up and down a flight of stairs. All tasks an exoskeleton would be expected to ace if the technology were supporting a disabled person in the real world.

“Cybathlon was something new for us,” Neuhaus says. “It was a sporting event, not a demonstration of a prototype. The goal was to show your technology and win your race. But the biggest difference was that a fallible, unpredictable human being would be doing the racing, not an autonomous robot.”

The IHMC suit came together just eight weeks before the competition. Team engineers labored through 14-hour days. Neuhaus hired Daniel to work full-time as a paid staffer, training for six hours a day in the suit. He augmented his routine with daily 15-mile workouts in a manually powered wheelchair, and hours of swimming.

“We shared what we were doing open-source, we had a blog, but we had no idea what other teams were doing,” Neuhaus says. “We thought the ankle-joint actuator would give us an edge, but we weren’t sure. In the end, so much depended on Mark.”

“Zurich was an amazing experience right from the jump,” Daniel says. “You get around most disabled folks, and a fair percentage have a somewhat pessimistic take on life. But the people doing Cybathlon were all outgoing, energetic, optimistic—they didn’t feel sorry for themselves, and they were thrilled about the technology that let them compete.”

The team that left a lasting mark on Daniel, however, was from the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Mark Muhn, a then-59-year-old framing contractor from California paralyzed from the shoulders down in a ski accident, piloted Team Cleveland’s entry in the functional electrical stimulation cycling race. In this event, pilots pedaled a recumbent bike or custom-adapted trike around a track under their own power thanks to electrodes that stimulated their nerves and muscles. The electronic impulses came out of control boxes that all but one of the pilots had taped to their thighs. The exception was Muhn from Team Cleveland.

Muhn’s electrodes had been surgically inserted inside his body. Developed by Ron Triolo, Ph.D., lead engineer for Team Cleveland, the multichannel implantable pulse generator (IPG) could potentially improve performance in the bike race by 25 percent, a greater advantage than Daniel received from the ankle actuators in his exoskeleton.

Muhn smoked his competitors in the bike race, winning the gold medal by a half-lap margin over the silver medalist, who was half Muhn’s age. “That impressed me, but what really fascinated me was the muscle mass on Muhn,” Daniel says. “His implants had stimulated his muscle fibers to grow. Increased muscle mass can improve your metabolism, blood lipid profile, bone density—practically every physical function. Mark Muhn actually had an ass to sit on. I hadn’t had an ass for nine years.”

In 2016, Daniel lined up for the finals next to Andre van Rüshen, a burly middle-aged German wearing a suit from ReWalk, a manufacturer of commercially available exoskeletons. The spectators packing the stands at the SWISS Arena stomped their feet and clanged cowbells. The couch challenge was first, and Daniel stood up and sat down deliberately and carefully. Heading for the straight ramp, he and Van Rushen were dead even. Daniel swung up the ramp and poked a door open with his cane.

Daniel pivoted to close the door, turning the entire rig 90 degrees, and as he did so he tipped back for an instant. Two spotters leaped forward to catch him, but Daniel righted himself, regaining his balance. He poked the door closed, swiveled again, and swung down the ramp to engage with the next challenge: walking a stepping-stone course without missing any of the stones. That was where the gamesmanship began.

The rules permit you to omit one challenge, and the German chose to bypass the stepping stones. It’s worth fewer points than the next challenge, the tilted ramp, which Daniel and IHMC team had decided to skip. During practice runs in the lab, their exo had performed awkwardly on the tilt. “I was able to complete it,” Daniel says, “but as a team, they decided that it wasn’t worth the risk.”

Daniel nailed the stepping stones and walked around the tilted ramp. He and van Rüshen were even again as they headed to the final challenge, the stairs. The crowd noise pumped up a notch.

Daniel poled up the stairs facing forward. Reaching the platform, he suddenly realized his right cane wasn’t tethered to the exoskeleton. “I felt that cane starting to slip, and if that happened, we were toast. You can’t walk an inch in the exo without your canes,” Daniel says. Everything went clear. He reached out and grabbed the the cable that linked it to the suit and snatched the cane back into his hand.

For better balance and control, Daniel descended the stairs backwards. Then one more battleship turn, and he and van Rüshen crossed the finish line in a dead heat. Because of the skipped ramp, the German won on points, 552 to 545.

Shortly after he returned from Cybathlon 2016, Mark Daniel embarked on another, even more ambitious adventure: a wheelchair trek across the United States. Daniel journeyed solo, on a standard, manually powered wheelchair largely unmodified for long-haul travel. On a cold morning in March 2017, Daniel started with his wheels in the Atlantic Ocean, on the beach in Delaware.

“Far as I could tell, no one had ever done that before,” he says. “Turned out, I couldn’t do it either.” He made it 352 miles to a mountain in Western Maryland, but developed pressure sores on his lower back that required bed rest to heal. “It was disappointing,” Daniel says. “But I learned a lot.” He’s planning a second shot in early 2021, after the next Cybathlon and the Toyota Mobility Unlimited Challenge finals, which he and the team qualified for in 2019, and which came with a half-million-dollar prize and a trip to Tokyo.

Daniel’s trust in the wheelchair is absolute. “After 12 years in the chair, there isn’t anything I can’t make it do,” he says. The exo simply isn’t as reliable yet. “It better be foolproof,” he says. “And that’s the case for the great majority of people with lower-limb paralysis. Until that turns around—and I’m convinced it will—the exo’s going to be a tough sell for disabled people. I love piloting it, but it’s not my way out. I’m doing this for some 18-year-old disabled kid in the future. Years from now, that kid’s going to stand up and walk in an exoskeleton with all its bugs ironed out. That exo’s going to be affordable, and as easy and natural to use as a wheelchair is today.”

Daniel takes a similarly measured, long-term view of IPG technology. With the Team Cleveland research group financing the procedure in exchange for Daniel volunteering as a test subject, he underwent the difficult surgery in December 2018 at the VA hospital in Cleveland.

“It took 12 hours,” Daniel says. “First I got this—” He lifts his shirt to show the outline of a cigarette-pack-sized box bulging the flesh of his abdomen. “—and then they wired it up to electrodes in 16 places around my body.” Daniel lifts his pant leg to show one of the two-inch scars from the 16 separate incisions.

IPG surgery carries a high risk of infection, and the electrodes often wear out. Mark Muhn has endured three separate surgeries over the last seven years, ranging from 5 to 12 hours duration.

“Is it worth it? Absolutely,” Muhn says. “Everything is working better—increased muscle mass, circulation, metabolism, strength and endurance, bone density. With the functional electrical stimulation hookup on my bike, I can ride outside in a park instead of being stuck inside a gym.”

Daniel reports similar results. “Last week, when I got out of the shower, I could see definition in my calf muscle,” he says. “And I’m steadily building an ass to sit on.”

Yet he also acknowledges IPG’s limitations. Daniel can only grow muscle mass when exercising on the recumbent bike connected to the device activating the implants. “The rest of the time, all those wires are just dead weight inside of me,” he says. By the same token, although researchers in Cleveland are working on one, there is not yet an interface between Team Cleveland’s IPG and IMHC’s exoskeleton.

That means, unlike Muhn, Daniel won’t directly benefit from his implants when he steps to the starting line for his race at Cybathlon 2020. But to stand, to walk, and to know that future generations will likely regard today’s exoskeleton the way we look at the Wright Brothers’ airplane—all of that will be reward enough.

You Might Also Like