From biplanes to Cold War satellites, new study unlocks mysteries of ancient Roman forts

Building on an amazing collection of aerial photographs shot in the 1920s from a biplane flown by a Jesuit priest, researchers who just published findings in the journal Antiquity used declassified Cold War satellite imagery to reveal another 396 sites of ancient forts along the former eastern border of the Roman Empire.

And the new data is helping evolve theories about what purpose the system of outposts served in an area that crosses the heart of the Fertile Crescent.

A former World War I pilot, Father Antoine Poidebard leveraged his aviation experience in the nascent era of the airplane to undertake “one of the world’s first aerial archaeological surveys, using a biplane and a camera to document hundreds of ancient forts and other sites throughout what today is Syria, Iraq and Jordan,” researchers wrote.

Poidebard’s work was notable as one of the earliest examples of putting aerial photography to work as a tool for archaeological research. And his documentation unveiled hundreds of previously unknown sites of Roman-period forts and defensive installations along the eastern periphery of the empire, spanning an area over 600 miles long.

Researchers Jesse Casana, David D. Goodman and Carolin Ferwerda published a paper this week detailing their work that merged information gathered by Poidebard and other previous research with their own analysis of declassified images gathered by some of the first spy satellites ever deployed. Focusing on an area that encompasses some 300,000 square kilometers in a region that extends from western Syria to Northern Iraq, the researchers utilized photographs taken by the U.S.-deployed Corona satellite program that included imagery collected from 1960 to 1972 and its successor, another U.S spy satellite called Hexagon, that collected imagery from 1970 to 1986.

Having access to the high-resolution archival images was crucial to the new discoveries as researchers noted that the area has been severely impacted by modern-day land-use changes, including urban expansion, agricultural intensification and reservoir construction that has, in some cases, erased the archaeological evidence.

The research led to the discovery of 396 new Roman forts in an area that was the eastern frontier of a Roman Empire that encompassed, at its peak, some 2 million square miles of territory.

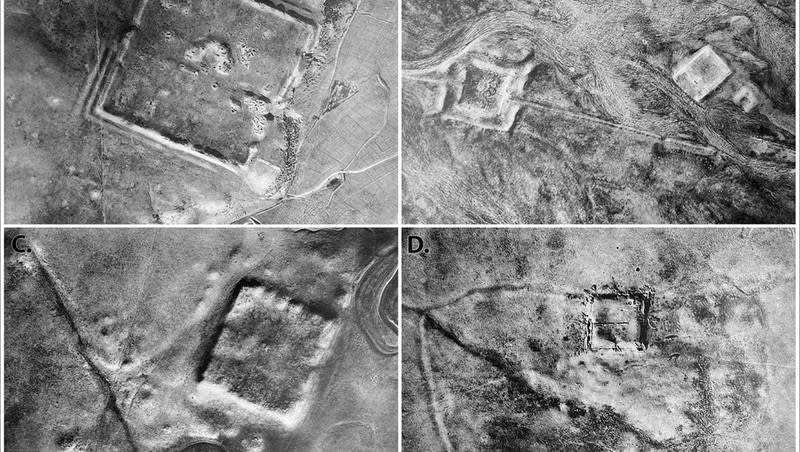

“These forts are similar in form to many Roman forts from elsewhere in Europe and North Africa,” lead author Casana, a professor of anthropology focusing on the Middle East at New Hampshire’s Dartmouth College, told Space.com in an email interview. “There are many more forts in our study than elsewhere, but this may be because they are better preserved and easier to recognize.

“However, it could also have been a real product of intensive fort construction, especially during the second and third centuries.”

Related

Researchers wrote that they believe current evidence suggests that most of the fort sites were constructed and used between the second and sixth centuries. Their discoveries also expanded the disbursement map, that includes evidence of thousands of ancient Roman structures in the study area. While previous theories leaned heavily into the idea that the system of forts was meant to be a fortification of the empire’s borderlands, researchers say the new data suggest many of the outposts may have functioned as way stations for trade and travel.

“The distribution of these forts suggests that they did not function as a border wall, with a series of towers and fortified encampments designed to block westward incursions by Persian armies or to prevent raids on agricultural villages by nomadic tribes,” researchers wrote. “Instead, our findings strengthen an alternative hypothesis that such forts supported a system of caravan-based interregional trade, communication and military transport.”