NEW: When a birth goes wrong, Florida’s ‘bad baby bill’ shields doctors, frustrates parents

Yamile “Jamie” Acebo lay in her Hollywood hospital bed, groggy and exhausted. Acebo, 20, had given birth for the first time two hours earlier, and she still hadn’t seen her baby. Her cousin, who was working a shift that night as a neonatal intensive care nurse, walked in. She wasn’t smiling.

Even through the fog, Acebo could tell Madeline Otero wasn’t there to offer congratulations. “She had her nurse’s hat on,” Acebo said, “not her cousin’s hat.”

She handed Acebo a Polaroid: A tiny newborn, lost in a tangle of tubes. A ventilator in her mouth. A drain from her stomach. An IV in her scalp, the only place nurses could find a vein. A heart monitor. Wires and cables.

As the gravity of what she saw gripped her, Acebo said a silent prayer: Oh my God. Lord, save her. Heal her. Make her better so I can take her home. Heal my baby, please.

Jamie Acebo had given birth to a “bad baby.”

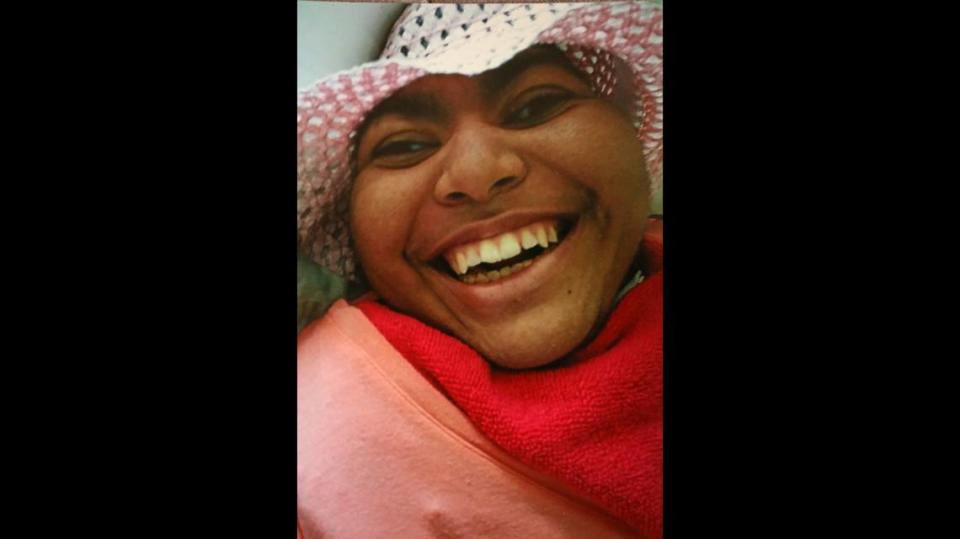

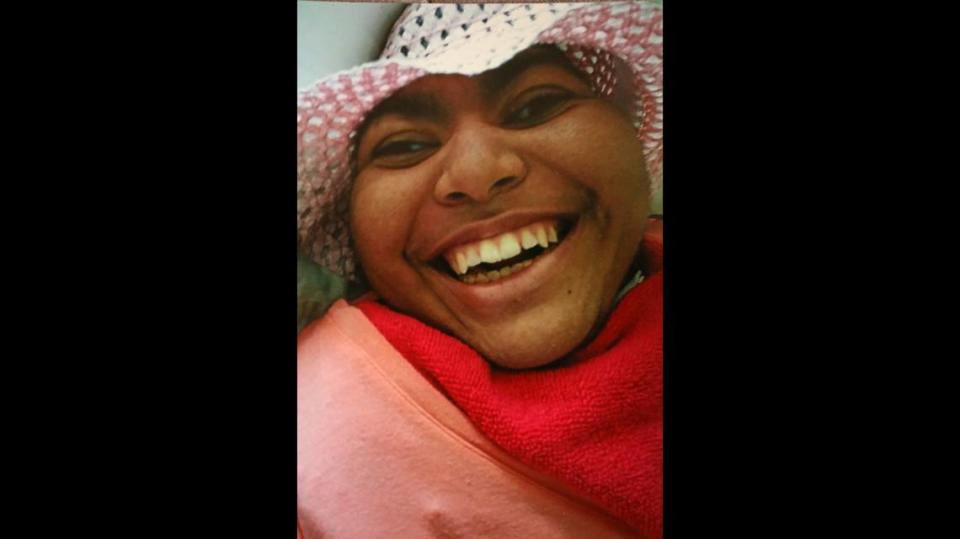

During delivery more than three decades ago at Memorial Hospital in Hollywood, the doctor trying to break Acebo’s water pierced the placenta that carried blood and oxygen to Jasmine’s brain. As her lifeblood drained away, so too did any chance for Jasmine to have a normal life. What she would have in abundance — besides unrelenting pain — was her mother’s devotion.

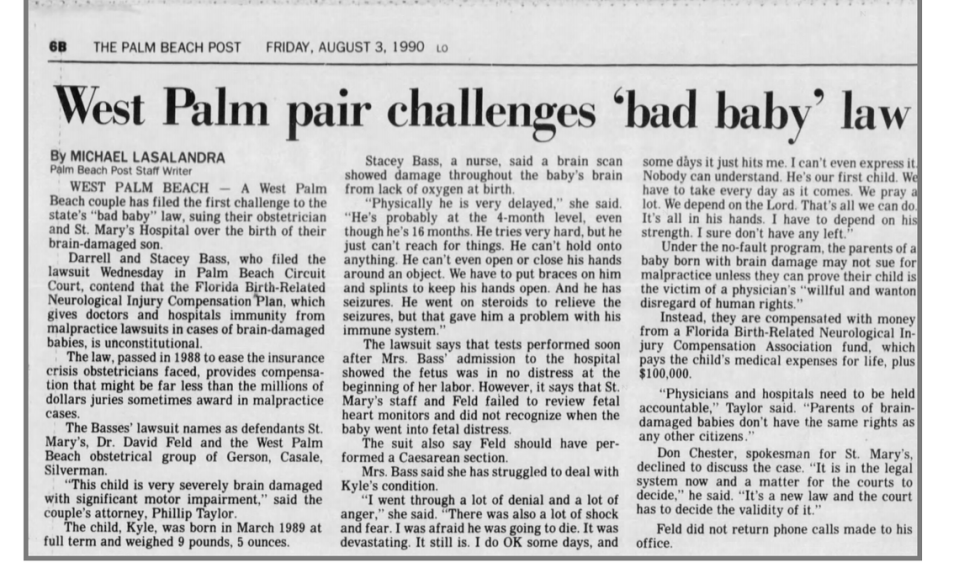

In every other state but one, Acebo could have pursued a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the doctor and hospital. But a Florida law enacted in 1988 — to reverse what advocates called an exodus of obstetricians fleeing high malpractice insurance premiums — stripped her of the right to sue.

Lawmakers informally called it “the bad baby bill.” Newspapers adopted the nickname.

The legislation was designed to protect obstetricians and hospitals from liability for colossal judgments and settlements when births went catastrophically wrong. It also created a quasi-governmental body, the Birth-Related Neurological Injury Compensation Association.

NICA, as the program is known, compensates families whose babies suffered severe brain damage. The program offers stricken families of profoundly injured children like Jasmine up to $100,000 up-front, and promises to help provide a lifetime of “medically necessary” and “reasonable” medical care. If a child dies, the program offers families an additional $10,000 for funeral expenses.

But from Jasmine’s acceptance into the program when she was three until her claim was “terminated” on the day she died in 2017, NICA’s own records show it broke that promise to Jasmine again and again.

Appeals and internal records show that Jasmine’s mother was one of many parents who spent years locked in frustrating fights with NICA after learning that $100,000 — the amount unchanged over 32 years — is not nearly sufficient to care for a tragically disabled child. They say NICA doesn’t tell them what benefits are available while rejecting or slow-walking reimbursement for often-expensive therapy, equipment, medical treatments, medication, in-home nursing care — even wheelchairs — that parents and their physicians consider essential.

Jasmine Acebo’s time in NICA dated back nearly to the program’s birth, making

mom — as much as anyone in Florida — an authority on the agency and her files an archive of its practices.

Jasmine’s special bed collapsed? No need to replace it, NICA said. It can be welded.

Jasmine’s energy-hungry bank of medical devices blowing the monthly power bill up to $500? NICA offered $25.

Jasmine’s outgrown her wheelchair? Stretch it out, said NICA.

“They were supposed to take care of her for the rest of her life,” Acebo said. “They were nickel-and-diming me for 27 years.”

*Denied the right to sue for Jasmine’s injuries, Acebo had no choice but to accept what NICA offered.

While Jamie Acebo and families like hers spend their children’s lifetimes fighting for care they believed they’d been promised by NICA, others benefit from the program’s advantages of legal immunity from medical mistakes.

Obstetricians, whose specialty is high risk and who are vulnerable to enormous legal judgments, get no-fault insurance for $5,000 a year — which hasn’t increased since the program began. Hospitals are shielded from suits for $50 per live birth.

Insurers, who now hold two seats on NICA’s five-member board despite contributing nothing financially to sustain the program, no longer face multimillion-dollar verdicts or settlements for injured babies covered by the law.

The law passes pain on to parents alone.

Part of NICA’s stated mission was to give a dignified existence and financial cushion for families crushed by the delivery of an infant with devastating brain damage. Instead of a world with strollers, pizza parties and nursery school, families are thrust into a nightmare of wheelchairs, feeding tubes and in-home nursing care. NICA promises help. The promise comes with an asterisk.

To assess NICA’s performance, reporters from the Miami Herald, in partnership with the non-profit investigative news organization ProPublica, examined court records, board minutes, actuarial reports, state insurance records, emails, legislative records, medical studies, archival records and case management logs for deceased children, as well as health department and financial services reports. They observed board meetings and interviewed parents, doctors, insurers, lawyers, ethicists and healthcare administrators.

Reporters examined all 1,231 NICA claims filed at the Division of Administrative Hearings, or DOAH, from passage until today.

The Herald filed a lawsuit seeking additional records, including emails and management logs that would show how NICA is handling cases of families served by the program. NICA administrators fought to keep the records secret, and a judge ruled in favor of the program, saying the families currently in the program have a right to privacy.

They found a parade of penny-pinching betrayals. These included spending thousands in legal fees to avoid spending hundreds in services for children, and two instances in which NICA hired a private investigator to tail families of disabled children to ensure they weren’t chiseling the program.

The investigation revealed:

▪ NICA has saved the state’s medical malpractice insurers hundreds of millions of dollars in payouts to families, largely by dumping those costs onto Florida and U.S. taxpayers. That is because NICA considers itself the payer of last resort on medical costs for NICA clients, pushing the burden onto taxpayer-financed Medicaid.

In turn, Medicaid, underfunded and notorious for erecting bureaucratic hurdles, rations care. Alexandra Benitez said Medicaid curtailed supplies for her son’s feeding tubes, and the tubes themselves, declined to pay for diapers, and refused to buy a machine to help Alexander Jay “A.J.” Benitez breathe. NICA would pay only after Benitez spent months appealing Medicaid denials. A.J. died Jan, 29, 2015, at age 15.

“Everything my son needed, I had to fight for,” Benitez, 48, said. “They literally had to see us in despair in order to give us what we were entitled to.”

▪ By suppressing malpractice litigation that can reveal evidence of a physician’s incompetence, NICA has shielded obstetricians from oversight. NICA cases by themselves almost never yield sanctions from the state Department of Health, though health regulators receive a copy of every NICA petition to review for malpractice. The historically weak health department has imposed discipline, which can range from reprimands to license revocation, to just six physicians in NICA’s history.

Ruth Joseph Jacques filed a health department complaint in 2016 after her 96-day-old son, Reginald, died from his birth injuries. She was told by DOH that her son’s delivery did not “violate the standard of care,” and the complaint was dismissed. The full findings of the investigation are secret, even to Ruth Jacques. Every year since, Jacques said, she has filed a new complaint on Reggie’s birthday and on the day he died.

“I know every time I file one of these reports, he also gets a copy,” Jacques said of her largely symbolic gesture. “For as long as I live, every single year, I’m going to file that report.”

▪ Reporters found cases where doctors and hospitals accused parents of being unfit after they rejected NICA benefits in an effort to sue their doctor. Parents will sometimes fight to avoid the program by arguing that their child’s injuries don’t meet its strict criteria — a child must be both physically and cognitively impaired to qualify — or that the doctor or hospital didn’t pay annual premiums. That can lead to expensive court battles with dueling doctors and anguished parents.

In hopes of avoiding a huge judgment, hospitals will ask a judge to appoint a guardian with the authority to usurp parents’ rights to decide what’s best for their child.

A Pinellas County hospital said Ashley Lamendola had a “conflict of interest” with her severely disabled son by refusing NICA’s $100,000 offer, and petitioned a judge to strip her of the right to pursue a lawsuit. “I was shocked. I was hurt. I was offended,” she said. The judge backed Lamendola, and the hospital’s insurer ultimately paid $9.5 million to settle her suit.

▪ While many NICA families live paycheck-to-paycheck, NICA has prospered, as have those who profit from it. The program doles out approximately $3.5 million annually to investment managers. Like virtually every Tallahassee entity, NICA has lobbyists, who are paid nearly $100,000 every year — a total of $876,000 since 2011 — to, among other things, fend off efforts at legislative reform. After the Herald/Pro-Publica began investigating NICA, the image-conscious administrators hired a public relations firm for close to $100,000.

NICA paid lawyers nearly $3 million to wage an 11-year fight against parents who sought compensation for giving up jobs and careers to care for their disabled children — a suit NICA ultimately settled, giving parents essentially what they wanted.

“It’s a scam,” Alex Sink, Florida’s chief financial officer from 2006 through 2010, said of NICA. “The pot is getting bigger, and people are feeding off the investments. They have no incentive to reduce the money in the fund in order to help parents. The priorities have gotten totally misplaced.”

The realization that NICA, not their doctors, decides what is “medically necessary” for their child is a source of outrage for parents in the program. The Herald found instances of Medicaid or NICA questioning the medical necessity of wound-care supplements, medication for seizures, education therapy and feeding bags for children with gastrostomy tubes.

The parent of a severely disabled child pleading for help with the cost of air conditioning during the withering heat of a Florida summer was told: “AC is wonderful and we all want it, but it is not medically necessary.”

Citing federal privacy laws, NICA administrators declined to discuss any specific children or families who are or have been in the program, except in cases where the Herald obtained a confidentiality waiver from parents.

Administrators also declined to speak directly with reporters, but answered almost 50 questions in writing. They said lawmakers “created NICA to solve a specific challenge” — the rising cost of malpractice insurance for obstetricians — “and it has done so very well.”

“We are proud to manage one of the state’s most fiscally sound programs, maximizing the impact of every dollar,” NICA said in a written statement.

NICA quoted a 22-year-old report from the Journal of the American Medical Association that NICA recipients were more pleased with the care they got than parents of disabled children who filed lawsuits.

“NICA remains committed to helping its families and children improve their quality of life, which includes palliative, habilitation or rehabilitation care,” the program said.

In the early years after entering the program, Rock and Shawna Pollock fought with NICA constantly: over reimbursement for a blender, feeding bags, mileage to and from the hospital, home renovations and therapy equipment, records show. “They’re trying to nickel and dime us,” he said in a 2011 deposition. “Right now we’re living in hardship.”

But in a December interview, Pollock said his relationship with NICA has since improved and he now owes much to the program, which has helped the couple provide for their disabled son, Rock Jr. “The only people that’s there for my family is NICA,” the elder Rock Pollock said. “They take care of him.”

Susan Camacho’s grandson, Jesus Camacho, whom she is raising, is a current NICA claimant. “NICA has never disappointed us,” she said.

Many things can go wrong during childbirth, but NICA covers only one — a specific type of injury to the brain or spinal cord of a live newborn caused by oxygen deprivation during labor, delivery or immediately after birth. For NICA to compensate such cases, the newborn must have weighed at least 2,500 grams (5.51 pounds) and the injury has to occur in a hospital.

Most children accepted into NICA are diagnosed with a condition called hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, in which oxygen deprivation and limited blood flow cause damage to a baby’s brain during childbirth. HIE can result when the umbilical cord is wrapped around a baby’s neck, or when a mother’s uterus ruptures. Delays in performing Cesarean sections can contribute to brain damage.

HIE is the third-largest cause of newborn deaths worldwide, and the fifth-leading cause in the United States, said Santina Zanelli, a specialist in neonatal medicine at the University of Virginia medical school. Researchers estimate that between 1.5 and 2 of every 1,000 U.S. newborns suffer from the condition, or about 6,000 to 12,000 children per year. About 20% of those newborns die, Zanelli said.

Since NICA’s inception, more than 1,200 families have petitioned for coverage, an average of three claims per month. A little more than a third — 429 petitions — have been accepted for compensation. Of those accepted, 143 children were deceased when their parents applied for compensation. Others died after their claim was approved.

As of Sept. 30, there were 213 clients in NICA, most of them still children, and at least 29 families had pending cases before the Division of Administrative Hearings, where judges decide which claims are accepted.

Pending cases include two newborns who died shortly after birth, and three petitions filed under protest, meaning the parents want to avoid NICA and file a medical malpractice lawsuit against the doctor and hospital instead.

While some parents whose children have truly catastrophic disabilities want out of NICA in order to hold their doctor and hospital accountable in court, others — including those whose children have milder disabilities on the cusp of NICA criteria — desperately want in, at times, fearing that a lawsuit won’t bring sufficient compensation to provide for the needs of a disabled child.

Though legislators designed NICA so that parents could apply for coverage without an attorney, the process can be overwhelming for those who are newly thrust into the role of full-time caregiver for a disabled newborn.

One West Palm Beach woman applying for NICA coverage without an attorney missed an important deadline in January, potentially jeopardizing her case.

“I am honestly just overwhelmed with taking care of [the girl], with her intense condition, trying to work while maintaining the busy schedule of her therapy and school,” she wrote, pleading for an extension.

The judge granted her request. The case is pending.

$1.5 billion and growing

Delaina Parrish is a rarity among NICA children: Though born unable to walk or communicate verbally, she uses a computer that tracks the movement of her eyes and can generate words or sentences on a computer screen or through the computer’s voice. The technology was provided by the manufacturer, not NICA.

Now 23, she’s a University of Florida graduate with a consulting business and a platform from which to advocate for others with disabilities. She was accepted into NICA when doctors believed it was likely that the 11 minutes she was deprived of oxygen would impair her mind, as well as her body. But Parrish’s intellect is as vibrant as any.

In a recent interview, Parrish said the program “only looks at what is required at the minimum” when deciding whether to help families.

“If we don’t have their financial support,” she added, “we can’t live our best lives.”

When deciding which requests to grant as “medically necessary,” NICA staff, including those with training in healthcare fields, often defer to Kenney Shipley, NICA’s executive director, records show. Shipley, paid $176,900 a year, is a former insurance claims adjuster and holds no license to practice medicine in Florida.

If some parents claim NICA is devoid of compassion, there is one thing that NICA has in abundant supply: money. The pot sits at nearly $1.5 billion and growing.

In the budget year ending on June 30, 2020, NICA earned six times as much in investment income, $124.6 million, as it spent on families’ of brain-damaged children: $19.8 million.

The program paid its lawyers $16.9 million between 1989 and 2020 — more than NICA spent, combined, on therapy, and doctor and hospital visits for children, during the same period, about $10 million. And unlike the standard settlement awarded to families, the money paid to NICA’s attorneys has increased over the years.

In 1996, the then-NICA director, Lynn Dickinson, declared it “unfair” that lawyers were being paid the same as in 1988. The board agreed, and voted an increase in lawyer fees from $75-per-hour to $110. NICA lawyer fees now range between $150 and $400 an hour, depending on the task.

Hired in 2002 at $118,000 a year, Shipley, who supervises a staff of 16, currently makes $30,000 more than the director of the state Agency for Persons with Disabilities, who heads a department with a $1.4 billion budget. She out-earns state agency heads who oversee tens of thousands of employees — and the health and welfare of millions of Floridians.

In its rationing of care, NICA typifies much of the state’s effort on behalf of Floridians with special or critical health needs: Florida ranks either at or near the bottom for virtually every measure of the state’s spending on services for people with disabilities.

“NICA is set up like most insurance companies,” said Sean Shaw, who served as the state chief financial officer’s consumer advocate from 2008 through 2010. “It’s set up to not pay claims.”

A father pleaded for reimbursement of the cost of a blender to puree fresh fruit, vegetables and meat for his 5-year-old’s feeding tube.

A mother wanted a nurse to care for her child on the school bus.

The parents of a 3-year-old girl, bedridden because of kidney stones and compression fractures on top of her disabilities, requested reimbursement for a TV and VCR so she could watch educational videos while convalescing flat on her back.

Answers: No, No, and see you in court.

To parents who spent years asking NICA for help, the rejections sometimes felt like condescending lectures. From emails and other records:

The blender: “We need a medical reason why [the child] needs blenderized food rather than baby food, which is already pureed and available.”

The school bus nurse: “NICA does not pay for nursing services at the school.”

The TV: “Televisions are normally the responsibility of the parents.”

The request for the $500 TV/VCR metastasized into a years-long courtroom battle over what grew into a laundry list of issues. In the end, the fight cost NICA more than $160,000 in legal fees.

And NICA sometimes rejects a specific request from one family — only to approve it for another family later. Shipley told Jamie Acebo that she could not pay Jasmine’s longtime personal nurses while Jasmine was hospitalized with gallstones in May 2016. This year, she offered to do exactly that for another family whose daughter is hospitalized with COVID.

A bill introduced in the Florida legislature in 2013 would have required NICA to operate “in a manner that promotes and protects the health and best interests of children” in its care.

The bill required NICA to inform families in writing each year of the “types and full amounts of benefits available from the plan for the injured child’s” projected needs. And it proposed adding a NICA parent or guardian, as well as a Florida lawyer, to the board of directors.

Shipley and her board had no interest — and they discussed efforts to kill the bill in a series of emails obtained by the Herald. In a September 2013 email to NICA’s lobbyists, Shipley dismissed the legislation: “Most of this is pretty silly since we are not here or funded to ‘promote the best interest’ of the children.”

The bill died in committee.

Banishing jurors

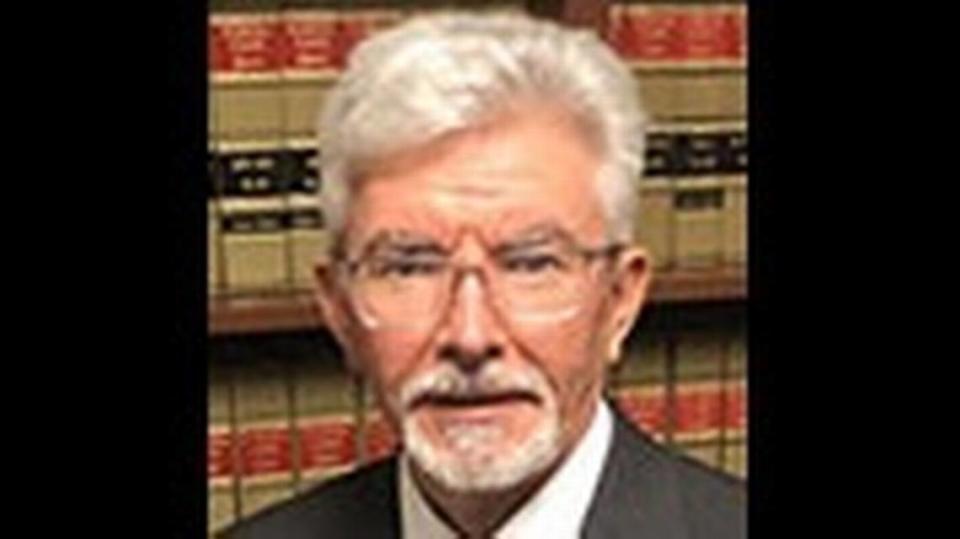

R. Fred Lewis both defended and sued insurance companies before then-Gov. Lawton Chiles appointed him in 1998 to the Florida Supreme Court. He and his wife also raised a severely disabled child, although one not covered by NICA.

Lewis, now a law professor at Florida Southern College, called the claim that doctors were fleeing the state — the justification for NICA — an “absolute lie.”

“But If you tell a lie long enough and hard enough, people will believe it,” he said.

Lewis said NICA was in fact part of a broad-based state and national movement aimed at expelling jurors from the civil negligence system — an effort that sought to minimize compensation for plaintiffs by leaving justice in the hands of administrative judges, who are appointed by the governor and cabinet and don’t answer to voters.

“They put in hearing officers who are, for the most part, political hacks,” Lewis said.

DOAH, which hears legal challenges to state agency rulings, “takes these decisions out of the hands of your neighbors and the people in your community who can intelligently look at the evidence and make a decision,” Lewis said. “They are trying to do away with jury trials in the state, and I find it very troubling.”

Florida lawmakers lauded NICA as a win-win tradeoff: While families forfeited their constitutional right to a day in court, they received a guarantee of cash and lifetime care.

But if NICA was a trade-off, parents were cut out of the equation. In addition to the president of Florida’s largest malpractice insurer, the Doctor’s Company, NICA’s unpaid board includes two physicians, a hospital administrator, and the board chairman, Charles Lydecker, who is designated as the representative of Florida citizens. His day job is running an insurance company.

In its 32-year history, NICA’s board has never included a parent or an advocate for disabled or medically fragile children. In 2013(ck), when a lawyer for NICA parents suggested it might be a good idea to have a mom or dad on the board, administrators refused to consider it.

NICA says it “expressed concerns” about adding a parent to its board because such an appointment “could lead to the perception of favoritism by other parents in the NICA program.”

Today, the $100,000 paid to families buys half of what it did in 1988. Also unchanged is the $5,000 assessment for obstetricians, even as the cost of every other type of insurance, including standard malpractice insurance, has shot upward.

NICA says it has no control over the $100,000 parental award or the obstetricians’ assessment. Both are set by lawmakers. “We recognize,” the program said, “that $100,000 doesn’t go nearly as far as it did 30 years ago, so the NICA board accepted a staff recommendation to raise the initial payment” to $250,000. The proposed increase is before the Legislature this session.

That proposal, initiated after the Herald and ProPublica began investigating NICA and submitting questions, serves a second purpose: In a February 2020 internal email, one of NICA’s publicists noted that, even if the amendment wasn’t approved that year, “making a public announcement about [it] “would help greatly to insulate NICA against media criticism.”

One way NICA administrators hold down spending is to strictly define what medical care is necessary. While Medicare defines medical necessity as any procedure needed to diagnose or treat an illness or injury, NICA takes that definition a step further — denying care that might help improve a condition.

Asked by a NICA attorney what constitutes medical necessity, one of NICA’s pediatric neurology consultants offered this explanation in a 2005 sworn statement: “if it were not administered, there would be a worsening of a patient’s medical situation.”

Internal records show that when parents ask for money not just to prevent a worsening but to improve the lives of their disabled children — even when those requests are endorsed by a doctor or therapist — they often receive an emphatic no.

David and Esther Morgan encountered NICA’s interpretation of “medical necessity” in 1997 when NICA refused to pay for a TV and VCR so 3-year-old Melinda Morgan, at the time enduring the misery of kidney stones and compression fractures on top of her profound birth injuries, could watch educational videos in her bed, and, in the words of her behavioral therapist, who endorsed the request, “escape the pain and frustration of her physical condition.”

Her father appealed, and was grilled in a deposition by a $110-an-hour lawyer from NICA, David Black, who wanted a sworn pledge that no one else in the family was watching the TV.

Letter to NICA by Casey Frank on Scribd

He got it — and still NICA opposed the $500 cost of the television and VCR to go with it. The Morgans’ battle with NICA would expand like a tumor, ballooning into a years-long legal fight over an ever-increasing list of issues, ranging from in-home nursing care to accessibility modifications to the Morgans’ home. NICA didn’t like the judge’s ruling, appealed, then settled in an agreement that remains secret except for the cost of the lawyers: $163,000.

Despite the yearslong legal battle, David Morgan still relies on NICA to help with his fragile, now 27-year-old child, and has made his peace with the program.

“NICA has turned out to be a lifesaver. I would be in total bankruptcy if it weren’t for NICA.”

Once, NICA’s then-administrator and medical consultant took a $2,009 trip to Costa Rica to avoid reimbursing a mother and child’s trip to Hungary. The mother, Flor Carreras, was seeking a new therapy that could free her daughter, Maria Theodora, from a lifetime attached to a feeding tube.

Starved of oxygen in the womb, Maria Theodora was born in February 1989 with severe brain damage and dysphagia, a disorder that makes it difficult to swallow and caused chronic lung infections and recurring fevers.

Carreras found hope for Maria in a Hungarian doctor who used electrical stimulation of the palate and throat muscles to help children overcome the disorder. Insurance wouldn’t cover it, though Maria’s pediatrician and therapist recommended it. She asked NICA to pay for the therapy in May 1993.

NICA said no. Carreras took Maria Theodora to Budapest anyway, and then asked an administrative judge to make NICA reimburse her for the treatment and travel expenses.

Maria’s pediatrician said she was later able to swallow small amounts of water and small pieces of soft fruit. She also had fewer fevers, a stronger cough reflex, and less drooling and wheezing — evidence of less aspiration.

Carreras’ determination to give her daughter the simple pleasure of eating would prompt a three-year legal tussle — and a trip by NICA’s administrator and consultant to the former Florida family’s new home in Costa Rica to judge for themselves whether the girl had benefited. In December 1995, a Miami appeals court sided with Carreras, ordering NICA to pay for the treatment — and the litigation.

The total bill for Maria Theodora’s treatment was $11,058. The fight over it: $80,000 in fees and costs for the family’s lawyers, whom NICA ultimately was ordered to pay, and about $44,000 for NICA’s own lawyers.

Tort Wars

NICA emerged in an era when insurers blamed jury verdicts for escalating premiums on medical malpractice coverage for doctors, particularly obstetricians, whose errors could cause ruinous disabilities requiring a lifetime of care.

At the time, the Legislature passed several laws to clamp down on verdicts, including ones calling for mandatory arbitration and pre-suit investigations. Lawmakers imposed hard caps on wrongful death malpractice suits — though they were overturned in 2014 by the Florida Supreme Court, which called them arbitrary, discriminatory and a constitutional violation.

Because NICA covers only one specific type of birth injury, obstetricians still need malpractice liability insurance for other potential risks.

Lawmakers modeled NICA after the only other program of its kind, in Virginia. Florida legislators claimed obstetricians were fleeing the state to avoid onerous malpractice premiums in the 1980s.

But it appears the record never supported the theory of an exodus of obstetricians: The number of Florida ob/gyns grew from 535 in 1975 to 911 in 1983 to 1,045 in 1987, the year before NICA was adopted — a 95% increase. In that same span, Florida’s population grew 44%. As of last June, the most recent tally, the number of Florida obstetricians was approximately 2,000. NICA administrators, however, say today that there was “an actual exodus of obstetricians from the state’s hospital delivery rooms” as doctors chose to limit their practice to gynecological care.

An organization of Florida ob/gyns commissioned an actuarial study of NICA in 2014, which found that the program saved obstetricians, on average, $57,535 a year in the cost of their malpractice insurance. Most obstetricians still carry malpractice insurance for claims not covered by NICA, such as severe shoulder injuries that can leave lifelong damage. 2015 ACOG report.

Though NICA may function like an insurance carrier, some of its practices exist virtually nowhere else in the insurance world.

Nearly every time they submit a bill, families are required to sign “perjury statements” attesting at the risk of criminal prosecution that they are not committing fraud. That includes minor invoices for lab tests, medications and travel to doctor appointments.

NICA says it insisted on the measure “to prevent healthcare fraud” after “unfortunate instances of some claimants falsifying documents and misrepresenting payments when seeking reimbursement.”

In one case, a mother complained to NICA about the suspicion she endured when simply trying to get reimbursed for her child’s medications: “She spoke for about six minutes straight about how humiliating it is for her to deal with NICA,” and “having to deal with employees who laugh at her and her troubles” a case management log said.

‘Less-than-optimal infant’

Jasmine Acebo was born on July 26, 1989. She suffered from seizures almost immediately. Two months after Jasmine’s birth, a neurologist told Acebo her daughter’s skull, which would normally seal at around age two, was already closing, which meant the infant’s head had stopped growing before her brain was fully formed. She was told it would be a miracle if her daughter survived.

Acebo faced a future she could not comprehend. A friend, a paralegal who had just delivered a stillborn baby, made an appointment for Acebo to see a lawyer, and accompanied her to the consultation. When Acebo described the case to the lawyer, he told her she couldn’t file a lawsuit because of NICA.

Acebo’s response: “No freaking way!”

Sworn testimony in the NICA case describes how after Acebo’s placenta was punctured during an attempt to hasten labor, the child’s heart rate plummeted from the normal 150 beats per minute to 50.

“That’s bad, isn’t it?” a NICA-paid doctor was asked under oath in 1993.

“It sure is,” the doctor replied. “It’s as if they shut off the blood supply of this kid.”

“They got what we would consider to be a less-than-optimal infant,” the expert said. In more stark language, he also called Jasmine a “bad baby.”

By 1991, Jasmine had a permanent feeding tube and a tracheotomy to help her breathe. She constantly cried, and rarely slept, meaning Acebo rarely slept, “awakened by Jasmine’s gasping and choking,” the family’s lawyer wrote. Jasmine required round-the-clock care.

“Yamile must live every day of her life knowing that Jasmine will never say her own name, attend kindergarten, go shopping with her friends, have slumber parties, feel the thrill of driving for the first time, nor know the excitement of prom night,” her lawyer wrote. (page13petition)

Although allotted $100,000 by NICA, it wasn’t really Acebo’s to spend. Instead, the program used part of the money to pay debts on her behalf: $1,758 for assorted bills, a separate $1,422 to Goodyear Tire and Rubber, $587 to State Farm, and $232 to Texaco. Another $16,000 was earmarked for a vehicle at Sun Chevrolet. The rest, $80,000, was placed in an annuity — controlled by NICA. Program administrators no longer manage how awards are spent, except when requested by parents.

Acebo, who could not work because of the demands of raising Jasmine, received “$300 and something” in interest every month, she said.

NICA’s May 1994 acceptance of Acebo’s claim could have returned her life to something approaching tolerable. But Acebo says administrators did virtually nothing on her behalf until either she or her daughter’s nurse begged them.

So beg they did, and by age 11, Jasmine had a pump for her feeding tube, a pulse oximeter, a tank of concentrated oxygen, a humidifier for the trach, a nebulizer and other equipment paid for by Medicaid, the state insurer for needy and disabled people. NICA, which considers itself a “payer of last resort,” covers such things only if Medicaid refuses and denies an appeal, a process that can take months, even years, to play out.

Acebo’s electric bill spiked from about $100-per-month to $500, she said. In 2007, the electric company threatened to turn off Acebo’s power when her cumulative tab rose to $2,099, records show.

NICA paid what was in arrears, then offered an electrical offset of $25 per month as the new bills arrived, Acebo said.

As Acebo sunk into poverty and despair, NICA mentioned it could pay the mother to care for her daughter. For the first nine years of Jasmine’s life, Medicaid would provide only four hours of nursing care daily, meaning that Acebo became her daughter’s de facto nurse, learning how to suction a trach, use a gastrostomy tube and manage other medical equipment.

Though state law allowed NICA to pay Acebo a minimum-wage salary for caregiving hours beginning in 2002, no one told Acebo, she said. When Acebo learned she was eligible, she inquired about back pay.

NICA said no.

What Medicaid-funded nursing care Acebo could get often was unreliable. In one 2006 instance her case logs show, she called NICA to report that “the night nurse was sound asleep, the humidifier was empty of water, the machine was very hot and Jasmine was having trouble breathing.”

Some of Acebo’s greatest frustrations involved getting Jasmine from place to place: Acebo claims, and NICA’s records largely confirm, that she struggled for years with wheelchairs that were too small for Jasmine’s expanding frame, with her van’s stuck wheelchair lift, and with the van itself, which constantly broke down.

NICA told reporters it bought Acebo a wheelchair in 1999, and modified it in 2001. The program’s case management log, however, includes this 2005 note: “Cannot find where we have paid for a wheelchair for Jasmine.”

Acebo said Medicaid — not NICA — bought her daughter’s first wheelchair, and NICA retrofitted it repeatedly. “They kept modifying the same wheelchair,” she said. “I’m telling them the wheelchair isn’t fitting her properly and they’re just sending out mobility companies, and the guy is coming out and saying ‘look we can’t stretch it out anymore’.”

NICA bought Jasmine a new wheelchair on Feb. 10, 2006, the case management log shows. NICA said the chair cost $7,751. It took the program a year to acquire it.

There is no record of Jasmine getting another wheelchair. But in the ensuing 11 years, Jasmine stiffened with contractures. Her legs gradually drew up, splaying her knees outward — and drawing her feet inward — as if in some cruel, lotus-like pose. It eventually became impossible for Jasmine to fit in the chair, Acebo said.

Jasmine, who had gone for long trips around the neighborhood, even trick-or treating in her previous one — became a prisoner in her bedroom, Acebo said. “She doesn’t go outside anymore. I don’t have a way to get her outside,” Acebo said she told NICA.

Jasmine’s van was a similar story, Acebo said. In July 2002, NICA gave Acebo a modified van to use for Jasmine’s transportation. By May of 2005, the van’s wheelchair lift was broken, and it took nine months for NICA to fix it, records show. After that, Acebo said the van was frequently inoperable, and it sat in her driveway accumulating rust.

In April 2011, NICA signed over the van’s title to Acebo. “NICA will no longer pay repairs or insurance,” the log said. The notation added: the program would “pay for ambulance transportation for Jasmine when she needs to go to the doctor’s office” — suggesting NICA was aware the van wasn’t really an option.

NICA told the Herald Acebo “did not submit a request for another van.” Acebo said NICA knew — or should have known — that she was entitled to a new van because the handbook says vans will be replaced at “approximately 7 years or 150,000 miles.” Nine years had passed when NICA signed over the old one.

And NICA knew that the van had long ceased working, Acebo said, because the program paid for the repeated repairs.

“It is NICA’s understanding that this arrangement was a better fit for meeting the needs of the family, and that the family was pleased with this result,” the program said. Acebo said she was anything but pleased.

Jasmine’s many doctor appointments were especially challenging without a van, Acebo said. She would call an ambulance or transport service to take Jasmine to her North Miami pediatrician. But the stretcher was too big to fit in the office elevator, and the doctor would descend to the lobby and examine Jasmine there — in front of passersby.

When Acebo complained to NICA about her daughter being on public display, caseworkers suggested she find a doctor who would make house calls, she said. Acebo found a doctor whose office had wider elevators.

One saving grace was that the ambulance rides were Jasmine’s sole contact with the outside world: sunlight streaking in through the windows, a breezy gust before entering the building, people to watch in their go-to-work clothes. “Then she would come back home and go into the room,” Acebo said.

When Jasmine was a small child, NICA offered to make Acebo’s life easier. She said the agency’s then-director showed up at her door with a proposition: “What if we put her in some institution? And you can go visit her any time you like.”

Acebo was horrified: “I don’t care if I don’t get a dime,” she said she answered. “I will not put her in any institution. I will care for her until the day the Good Lord takes her home.”

NICA, she said, “wasn’t created for me. It wasn’t created for my kid.” She added: “They had all the power.”

‘Like having your stomach ripped out’

For Lewis, the retired Supreme Court justice, such stories of hardship and hopelessness hit close to the heart.

He and his wife, Judy, cared for a severely disabled daughter, Lindsay Marie Lewis, until her March 2012 death at age 26. Lindsay had been diagnosed with a rare genetic disorder that left her deaf, legally blind and unable to walk. Lindsay also required round-the-clock care.

“It’s devastating when the news comes: Your baby is injured. It’s just like having your stomach ripped out,” Lewis said. “That pain of not knowing what will happen when you are not around — that is a devastating burden to carry.”

Celia and Curt Lampert’s now-23-year battle with NICA has so far included three appeals to DOAH, a class-action lawsuit and three trips to the First District Court of Appeal in Tallahassee. The family’s relationship with their son Tyler’s healthcare provider became so antagonistic that they were one of the families surveilled by NICA’s private investigator.

NICA Class Action Attorney Summary by Casey Frank on Scribd

Tyler was accepted into the program in 1997, two years after he was born. Records show he suffered a severe stroke during or after delivery that made him prone to frequent and life-threatening seizures. His right hand is largely nonfunctional, and he walks with a pronounced limp. Brain surgery succeeded in stanching the seizures, but brought new problems: total vision loss on his right side and learning disabilities.

The Lamperts declined to discuss Tyler or NICA with the Herald, but the family’s history with the program is detailed in records at DOAH.

When Tyler was 7, Celia “Cece” Lampert asked NICA to pay $8,280-to-$11,040, for an intensive reading-comprehension program. “Even with all the work I have put into Tyler, he still has so much to overcome and could benefit so from this program,” Lampert wrote.

NICA refused. In a July 23, 2003, letter to the family, Shipley wrote the program “may be one that would help Tyler,” but that it was not “medically necessary.” The Lamperts appealed to DOAH a week later, but Administrative Law Judge William J. Kendrick ruled against the family.

On Oct. 6, 2003, Cece Lampert called NICA. A log of the call said she was “very angry that we hadn’t told her” that families could be paid for the time they spent caring for their children. “I explained that Tyler had never required nursing care, so we didn’t believe it would apply to them,” the log entry said.

That December, Curt Lampert called Kathe Alexander, NICA’s claims manager. “He is upset because he feels that we are playing God with his son’s health,” said the log entry. “He went on to state that he didn’t think Kenney or I cared.”

When Tyler was 9, the Lamperts filed another appeal with DOAH, which eventually included requests for a wheelchair, a wheelchair-accessible van, and an occupational therapy program in Alabama designed to improve muscle tone and dexterity in Tyler’s disabled arm. All had been denied by Shipley.

“Yes, the costs of this program are high,” Lampert wrote in a July 19, 2004, email to Shipley, “but how can you put, or anyone put, a price tag on Tyler’s care, rehab and well-being?” The 23-day therapy program’s cost was $12,000, plus lodging in Birmingham.

In letters to Lampert, Shipley wrote that the therapy appeared “to have some promise,” but was still considered experimental. The wheelchair, she said, was not necessary because Tyler was not wholly dependent on one the way more physically disabled clients were. And the same was true for the van, she wrote.

While the appeal was pending, NICA hired a Pompano Beach private investigator to shadow the Lamperts, who, by then, were in the process of moving to a suburb of Atlanta. The investigator billed for four days of surveillance — Aug. 4 through Aug. 7, 2005 — airfare, a hotel, rental car, meals and video, for a total of $5,328.

Investigator Joe Torres reported the quotidian details of Celia Lampert’s life: Lampert takes her son to an appointment at “Sunshine Therapy.” Lampert takes Tyler to Wendy’s. Lampert walks her “two small dogs on leashes.” Lampert buys dinner at a Burger King drive-through. Tyler and his mom visit Blockbuster Video. Tyler swims inside his hotel swimming pool, and dries himself with a blue towel. Mother and son shop at Target, and later eat at Chuck E. Cheese.

On Sept. 22, 2005, Kendrick declined Lampert’s request for the therapy, saying it was “experimental, investigative” and not “medically necessary and reasonable.”

Kendrick did order NICA to pay for a wheelchair, and to either retrofit the Lamperts’ Mercury Mountaineer SUV to accommodate the wheelchair or provide a specially equipped van.

Kendrick stated in his Aug. 8, 2005 order that NICA “failed to objectively consider Tyler’s limitations, and overlooked the testimony” of its own expert — who had been Tyler’s neurologist as well. He reported that “given Tyler’s physical limitations and inability to [walk] for extended distances or substantial periods of time, a wheelchair would be appropriate for his use.”

The truce between NICA and the Lamperts soon unraveled. In 2006, Tampa lawyer David Caldevilla filed a class-action lawsuit against NICA, claiming the program had been “unfair and deceptive” to the parents of brain-damaged children by refusing to pay for care given by the parents themselves, some of whom had been forced to quit their jobs. The Lamperts were joined by more than 100 other families.

In November 2012, the suit was settled, and three months later, on Feb. 22, 2013, Shipley wrote a letter to the Lamperts telling them they were eligible for 12 hours of subsidized caregiving each day — then withdrew the offer after the family and NICA disagreed over what the Lamperts were owed in back pay.

On Sept. 21, 2015, Judge Barbara Staros ordered NICA to restore the offer of 12 hours of care each day. In a footnote, Staros weighed in on one of NICA’s accusations against Celia Lampert, whose zealous advocacy for her son had so bedeviled NICA.

She wrote: “NICA’s characterization of Mrs. Lampert’s role in Tyler’s [care] as ‘over-active involvement and manipulation’ is rejected.”

Over 11 years, the class-action battle cost NICA $2.8 million, spread among nine law firms.

NICA also paid Caldevilla $86,610 in legal fees for representing the Lamperts. NICA has spent $412,446 in legal fees battling with Tyler’s family alone.

NICA administrators and their allies long have maintained families were satisfied with the program, and grateful they were spared the uncertainty and heartache of a protracted malpractice litigation.

“Recipients are seen to be receiving excellent care, and participating families are overwhelmingly satisfied with the level of service, and they support the system,” the Florida Obstetrical and Gynecological Society, wrote in a February 2007 report.

NICA’s own records over the past two decades, however, raise doubts. Around 2001, seven NICA families complained to then-Insurance Commissioner Tom Gallagher. NICA’s then-executive director, they said, concealed the benefits they were entitled to receive, failed to do any outreach and showed favoritism in dispensing needed care, meeting minutes say.

A survey by the Insurance Commission at the time found that more than two-thirds of NICA families polled reported they “were treated without care or kindness.”

When families threatened to take their concerns elsewhere, then-Deputy Insurance Commissioner Paul Mitchell said someone at NICA told them “they did not care if they complained to the governor,” meeting minutes said.

Another round of complaints — this time to lawmakers — prompted another survey. But this one, completed in 2012, reached a far different conclusion: that most NICA families were happy. The survey was administered by NICA’s paid lobbyists

The complaints continued. In 2017, the parents of Delaina Parrish — who astonished and delighted doctors by graduating college last year and launching a career despite her physical disabilities — attended a board meeting to urge administrators and board members to “help families.” Patricia and Jesse Parrish said NICA staff was “denial-driven,” not motivated by compassion, wouldn’t publish meeting dates, kept a strong grip on the spigot, and set arbitrary limits on what they’ll pay for.

The Herald asked the Parrishes late last year if the program has improved since then. Patricia Parrish said she is disappointed NICA still has not added a parent to the program’s board, continues to deny services arbitrarily, doesn’t inform parents of new benefits and won’t encourage other parents to attend meetings and offer input.

She said: “Why do they get to play God?”

NICA disputes that administrators don’t make families aware of their benefits and options. The program “regularly informs families in advance about care and services that might improve their situation,” administrators said.

As an example, the program noted it offered last year to buy $29,000 robotic “exoskeleton” suits to help some children improve the muscles in their legs. “NICA staff contacted all families with a child who could benefit from” the technology, NICA said, “and then assisted them with the process to get this new equipment capable of improving their daily lives.”

The offer was made at the same time that NICA hired its publicist — and was immediately pitched to news organizations. Shipley, the executive director, said in an email to the technology’s developer that NICA was “looking to do a positive news story” about the equipment.

A rented casket

Every year, Jamie Acebo wondered if it would be her daughter’s last. Her last birthday. Her final Christmas. The last time hearing her relatives tease each other around a Thanksgiving dinner.

In the winter of 2017, Jasmine was hospitalized with gallstones. Acebo had other children at home, so she arranged for Jasmine’s nurse to work her shift at the hospital, ensuring Jasmine was repositioned, bathed, her trach suctioned, her feeding pump refilled. Hospital staff wasn’t doing those things properly, or at all, she said.

Acebo and Jasmine’s nurses recognized the subtle, nonverbal signs others missed: Jasmine would grind her teeth and bite her lips when she needed medicine for the pain. That was the only way they knew, and could ask for pain medication.

When NICA administrators found out about the NICA-paid nurse deployed to the hospital, they moved to claw back $2,240 from Acebo, records show.

“We are not required to pay a private professional caregiver during a hospital stay,” Shipley wrote.

After an attorney pleaded Acebo’s case, Shipley offered to let Jasmine’s mom repay the money in $25 installments.

Jasmine’s prognosis wasn’t good. Acebo said one of Jasmine’s doctors reminded her that Jasmine was “not a productive member of society,” and had, in any event, exceeded all expectations by living more than a quarter-century. She said she was repeatedly encouraged to sign a “do not resuscitate” order.

“You know, she’s had a lot of miracles, and I think hers are just about up,” Acebo said she was told.

Acebo’s answer: “If God wants her, He’s going to have to come and get her, because I’m not signing a DNR.”

But as Jasmine’s condition worsened, doctors warned Acebo that the stress of reviving her would result in cracked ribs, one more excruciating indignity for a daughter who had endured them all her life.

On March 19, 2017, Acebo signed the DNR. She held Jasmine’s hands, stroked her face and whispered “Mommy loves you.”

“You don’t have to fight for me no more,” Acebo said. “You can go home.”

“And, once I said that, the monitors just started to go down.”

Nine days later, NICA finally wrote Jasmine Acebo off its books. The last entry in Jasmine’s case management log was a payment to a funeral home.

But even in Jasmine’s death, Acebo felt betrayed by the state, which had promised much, and delivered so little. Acebo was left with a choice: she could afford a funeral, or a burial, but not both.

The $10,000 NICA pays for a funeral was adopted in 2003,15 years after NICA was created.

Though Acebo’s Baptist faith eschews cremation, it was the only choice she could make: the cremation cost $6,500 — a casket burial twice that amount. For $3,000, she rented a casket that sat empty at the service.

Jasmine’s ashes now rest in an urn atop the dresser in Acebo’s bedroom.

NICA administrators told the bereft mom to forget about the remainder of the $25-a-month repayments.

On the day after Jasmine died, Jamie Acebo received an email from NICA. Administrators were sending Acebo her final caregiving paycheck for looking after Jasmine. The amount: $717.08.

She was owed more than that, but in keeping with past practices, NICA deducted $332.92. That was the cost, NICA said, of FedExing her checks for the previous three months.

Payment for Jasmine Acebo's mom by Casey Frank on Scribd