Births, deaths and a viral video: KC Zoo’s penguin exhibit draws acclaim and scrutiny

In 2019, the Kansas City Zoo, then six years into its penguin exhibit, flew in nine fertile macaroni penguin eggs from San Diego. They were cozy in an incubator, with their own seat on the plane.

In the coming months, it took hundreds of hours of care for zookeepers to hatch and hand-raise the eight surviving birds.

The chicks – named after popular cheeses – were a turning point of sorts for the Helzberg Penguin Plaza, which opened in 2013. No longer was the zoo the “Ellis Island” of penguin exhibits, as its CEO and executive director, Sean Putney, called it at first, taking in any birds, including the sick, the old, and the least popular. Finally, they were part of the crucial network of zoos helping to breed and raise penguins.

Georgia Eckett was among the animal care specialists devoting late nights, early mornings and weekends to ensuring the survival of the new chicks, taking the place of their feathered parents until they were healthy enough to join the colony at about 18 months old.

“They helped prepare me to be a mom, feeding those chicks baby formula and syringes at all hours of the night,” said Eckett, who at the time was pregnant with her first child.

“Penguins have just charismatic personalities and so it’s hard not to make that bond with them. We try not to anthropomorphize our feelings — putting human emotions on them — but we spend more time with the animals we care for than our family members most of the time, so it’s inevitable that you create a bond that’s hard to explain to someone who’s not here every day.”

The penguin exhibit ushered in a new era for the zoo as admission numbers rose to record levels. In a few months, the penguin exhibit will celebrate its 10-year-anniversary as the zoo prepares to open a $77 million aquarium. With the next major milestone on its horizon, a look back at the past decade reveals the trials and tribulations of launching a new exhibit. Birds have died, some at young ages. But the zoo has also become a key breeder for other accredited zoos, and credits the popularity of the penguin exhibit with helping to lay the groundwork for the zoo’s fortunes and future.

A popular livestream video of the exhibit even gave penguin lovers worldwide a 24/7 look at the birds in captivity. But while the camera was beloved by many, it also was an opportunity for some to criticize the zoo’s handling of the penguins, drawing on an increasingly nuanced conversation that gets at the heart of whether zoos should exist at all.

Since 2013, the zoo has been home to 136 penguins. Some were borrowed from other zoos and then returned. Some were born in Kansas City, while others began breeding there.

Of the 136, 19 have died at the zoo. Only two of the penguins that died lived beyond the median age of death for that sex and species in captivity, per the Association of Zoos & Aquariums. Half a dozen died as chicks.

Officials with the zoo, which is accredited by the AZA through 2026, and has been continuously accredited since 1984, say they’re doing the best they can. Deaths are natural, they pointed out, adding that a number of elderly birds have thrived in their care too. Four of the zoo’s current penguins are among the oldest in the country, at age 36.

The zoo has faced some negative attention in recent months after a Twitter user started posting videos from the zoo’s penguin livestream of some of the birds pecking at or chasing each other. As a result, the zoo decided to separate some of its oldest birds from the younger ones after the videos continued to gain traction on social media.

On Thursday morning, the zoo disabled the penguin cam, despite it reaching about 3 million views per year during the pandemic. They said they made the difficult decision as a result of the Twitter account, which posts recordings of their staff while inside the exhibit.

“Unfortunately, that popularity came with increased challenges that included the ongoing harassment of Zoo staff, so we have decided to end the live feed,” Putney said in a statement Thursday, later adding: “We know many will be disappointed by the end of the penguin cam and the Zoo shares their frustration, but we must do what is best for employee safety and wellbeing.”

But zoo officials maintain the bumps in the road are part of the journey, and said they’ve made great strides in establishing and nurturing a penguin exhibit they say is one to be proud of.

“Animal care and welfare is at the very base of what we do, and we’re continuing to look for ways that we can get better and better with each passing year,” Putney said. “So I would challenge those people who see an activist statement or a short film clip or something that’s negative about an accredited zoo or aquarium to go back and really look at the facts and the figures and what we really do and what we provide for the animals and for our guests.”

The popularity of penguins

In 2008, a year before the zoo celebrated its 100th anniversary, it was named one of the best zoos in America. But zoo leadership was still looking for a way to increase interest in the local attraction.

Two years later, voters in Jackson and Clay counties approved a sales tax increase to help finance zoo improvements through the newly-formed Friends of the Zoo, a non-profit that now runs the park. The one-eighth cent sales tax was expected to more than double the zoo’s budget in the first year. As part of the advertising to pass the tax, the city leaned heavily on imagery of penguins.

In 2013, as Friends of the Zoo members were given a sneak peak of the unfinished Helzberg Penguin Plaza, Putney, then director of living collections, told The Star: “I have no doubt that this will be one of the most popular exhibits here, and maybe the best in the country.”

In September 2013, the zoo unveiled its first major project since the change in ownership.

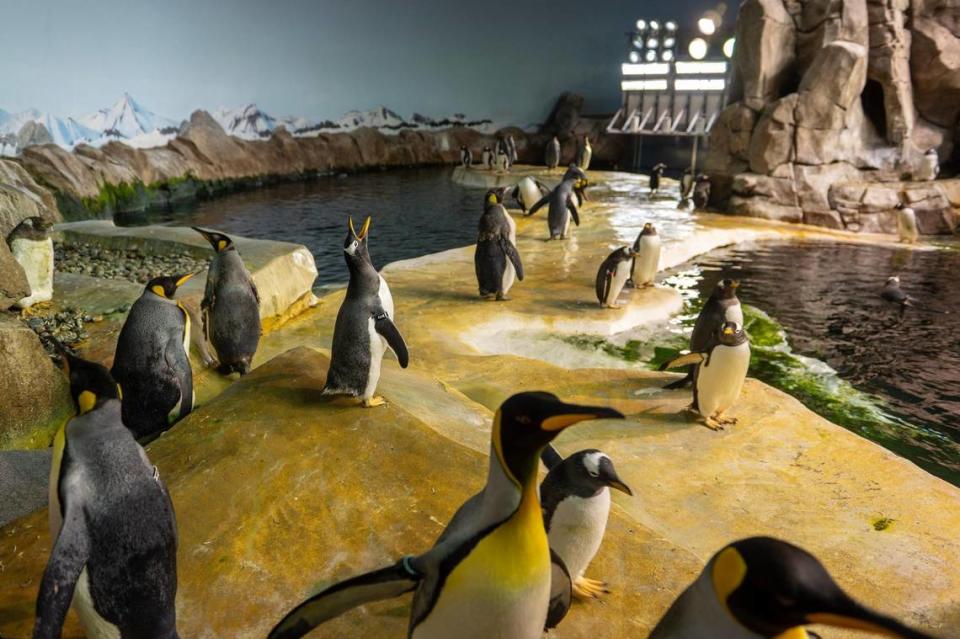

The $15 million penguin exhibit features a 100,000 gallon indoor pool for the cold climate penguins and a 25,000 gallon indoor-outdoor pool for the warm climate penguins. The exhibit spans about 17,600 square feet. The multi-million dollar filtration system turns over about 100,000 gallons of water every hour.

The exhibit opened to the public after three Humboldt penguins were escorted from the Sedgwick County Zoo to Kansas City. When the first penguins arrived, the exhibit had already drawn compliments from many of the roughly 2,000 zoo professionals from 16 countries who came to KC a month earlier for the AZA Annual Conference.

For the first time, Kansas City had penguins, thanks in part to a questionnaire sent out to guests and members who championed the birds.

It was positive press for the zoo after critical attention the year prior, when the zoo was reprimanded by the Department of Agriculture after a male chimpanzee died of starvation. The federal oversight agency found the animal weighed less than 94 pounds, compared to the normal weight of about 150 pounds for an adult chimpanzee. Staffers said they had been unable to weigh the 13-year-old animal, named Nusu, because the other chimps would not let him get to the food used to lure the chimps to the scale.

In 2013, before Putney was CEO, he led the animal care team and called the penguin exhibit a “turning point” in the zoo’s history; “the start of something new.”

“It was our way of showing the people in this town what we can do if we have the funding to do it, and what better way to do it than with an animal that everybody loves,” Putney said.

Within the first 13 months of the exhibit, nearly one million people had already shuffled through the zoo’s entrance, taking in the brisk air and fishy scents as they got up close and personal with animals that can’t be found in the wild in North America. The year prior, the zoo saw just over 880,000 visitors.

In 2016, the zoo surpassed one million annual guests for the first time in its then-107 year history. Though it hasn’t surpassed seven digits since then, the visitors numbered more than 900,000 every year from 2016 until the pandemic hit. The numbers haven’t quite recovered since; in 2022, the zoo was still about 7,500 visitors short of 900,000.

But there’s no doubt that the penguins are loved by the community. In the winter, the zoo’s penguin walks are one of the most popular ways of drawing people out of their warm homes and into the cold park to watch the penguins waddle outside their exhibit and past guests, with zookeepers leading the way. The zoo is now ramping up for their warm-climate penguin walks, which begin again Saturday. Inside the exhibit, it’s not uncommon to see a child in penguin paraphernalia pressed against the glass, trying to get a closer look at the birds speeding past underwater. A handful of people have even gotten married inside the penguin exhibit.

The people have kept coming, and so have the penguins. In May 2014, nine gentoos and four kings from SeaWorld San Antonio were gifted to Kansas City, bringing the total penguin population at the time to 61. That same month, the zoo’s first penguin hatched in-house: a Humboldt.

It died 37 days later of kidney failure.

‘Sometimes things happen’

Penguins in the wild, on average, die sooner than penguins in an accredited zoo.

So far, 19 birds have died at the Kansas City exhibit. Of those, five were chicks.

“You try to do your best. But also when you’re trying to let mom and dad raise them, sometimes things happen,” Putney said. “You just don’t know.”

The first year is the riskiest in a penguin’s life, biologists say.

“The first 30 days of a penguin’s life are the most traumatic, just like it is for us, and it’s the most dangerous part to get through,” Putney said. “We’ve had some chicks that died shortly after they hatched, we’ve had chicks that haven’t hatched.”

When a Kansas City penguin dies, its remains are shipped to a zoo out west in Washington where a necropsy – the animal version of an autopsy – is performed.

Kirk Suedmeyer, director of veterinary health and conservation research at the zoo, said he doesn’t have any “overriding concerns” about the health of the penguins upon studying the necropsy reports for each of the 19 deceased penguins. Copies of each necropsy were also provided to The Star.

“We review all animal demise from many different aspects,” Suedmeyer said. “And if there needs to be changes based on necropsy or histopathology, then we discuss it as an animal care group and address those changes.”

He defended the zoo, saying the “real story” is all the health issues they’ve prevented in the penguins, rather than the demise of a score of them.

But zoo officials acknowledged there have been some learning experiences as they wade through the challenges posed by starting a new animal exhibit.

Early into the new exhibit, two Humboldt parents hatched a chick, the first of its kind inside the KC exhibit. Three days before it died, the chick regurgitated 123 stones. More than 100 additional stones were found in its gizzard, according to the necropsy. Suedmeyer said the stones weren’t ultimately the reason for the chick’s demise, but rather, a fungal infection. But the stones were still a concern.

The chick’s parents had decided to lay their egg outside of the normal nesting box area, giving the chick access to small pebbles. After that chick’s death, the zoo changed the material in that corner of the exhibit to dissuade any other pairs from nesting there. So far, it’s worked.

A day at the zoo

By 9:30 a.m. on any given morning the animal care specialists are busy sorting fish. On a recent late winter day, this included about 40 pounds each of capelin and herring.

After being inspected for freshness, the fish are dropped in a bucket and carried out to the penguin exhibit, where the zookeepers hand feed each bird, dropping the scaly creatures down the penguins’ gullets, often in one swallow. Vitamins are hidden in some of the fishy feast.

Putney said they hand feed the fish to monitor their health. Each morning and afternoon, one zookeeper feeds, and another writes down which penguins ate and how much. If they notice an unusual eating pattern, they’ll check on the bird’s overall health.

Penguins’ appetites vary depending on the season. Late winter and early spring are molting time for the penguins, which often means they gorge themselves ahead of the molt, and then try to exert as little energy as possible as they push out their old feathers for new ones, Eckett said. Sometimes, digesting a normal bucketload of fish isn’t worth the energy.

Eckett likened this ragged state the birds go through as they push their old feathers out in clumps and grow new ones to a human’s awkward phase in middle school. Except penguins have to endure the mess every season. It’s why so many of the birds look disheveled at the start of the year.

In the afternoons, the penguins often get “the zoomies,” porpoising back and forth across the pool. Sometimes the younger birds, still getting the lay of the land, will overshoot their re-entry and belly flop back into the water on the other side of the island. Putney said it usually elicits laughs from lingering zoo-goers.

There are 90 penguins now. Putney hopes to continue growing the chinstrap and macaroni populations in particular, he said as a macaroni stood at his feet, tugging at his pant leg. But he doesn’t think the space could hold more than 100 birds and still allow enough room for nesting.

A Twitter controversy

Up until very recently, the zoo kept a 24/7 video of the penguin enclosure. The livestream, which often has hundreds of viewers at a time, drew curiosity from many and criticism from some.

A Twitter user in Japan began watching the livestream of the penguin exhibit religiously more than a year ago. Then she started recording segments of the videos and posting them on Twitter, concerned about some of the behaviors of the birds.

In one video, posted to Twitter on Dec. 12, a group of penguins chased another bird.

Macaroni is a violent penguin.

They keep attacking one bird in a group.

マカロニがマカロニを襲ってた

トラウマが蘇る…

ディジットも換羽中マカロニに全く同じ事をされた

血が出ても動けなくなっても1時間40分襲われ続けた

飼育員は助けに来なかった#KCZoo#animal #動物園 #ペンギン pic.twitter.com/Kacb0w2RGS— ペンギンちゃん (@ariel_digit) December 12, 2022

“I would say that’s highly unusual for so many birds to go after one penguin like that repeatedly over and over,” said Steven Emslie, a professor of biology and marine biology at the University of North Carolina Wilmington who reviewed the video. “The video is only 30 seconds, but I don’t know how much this went on before and after.”

Territorial disputes at nest sites are common in the wild, said Emslie, who for more than a decade has studied penguins in the wild. But he doesn’t recall seeing so many penguins “gang up” on another.

“It seems very unusual to me,” he said. “And it’s pretty brutal.”

Putney said they agreed some of the birds’ behavior toward certain penguins was “unusual,” though he said in most cases, the bird is able to get away, usually by hopping in the water.

For a few weeks in early 2023, the zoo disabled the livestream to conduct an internal review. They immediately began hearing from people and businesses across the metro that stream the video for customers and patients, including children’s hospitals, home day cares, and dentists. Even people as far away as the United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil and the Netherlands reached out asking where the video went.

The zoo eventually put the video back up.

“If we really had anything to hide, would we put a camera on it 24/7 and let 3.7 million views happen?” asked Kim Romary, a spokeswoman with the zoo, adding that the camera has helped fulfill their mission of connecting people to the natural world.

The review by the zoo’s animal welfare committee led to the decision to separate Gomez, an elderly bird who appeared to be the victim in some of the recent videos, from the other birds at night, when the animal care specialists weren’t in close reach.

But in late March, they decided to isolate Gomez, who is a gentoo penguin, and a few of the other elderly birds, for a longer period of time.

“He and a few other of our geriatric penguins are currently being housed separately from the rest of the flock so they can get more specialized care,” Romary said in an update on March 30.

The Twitter user continued to post videos of the penguins multiple times a week. Recently, after Gomez was taken out of the main flock, they wrote: “Zoos that lock up only the bullied penguin, take away her freedom, and say they have improved are wrong.”

The Twitter user also reached out to In Defense of Animals, an advocacy group, that also took notice of the videos.

“It’s heartbreaking to observe the penguin try to defend himself and get away from the attackers,” said Brittany Michelson, with IDA. “When wild animals are forced to live in cramped, unnatural areas they experience stress, which causes a greater propensity for bullying behavior. If these penguins lived in the wild, the bullied individual would have the space to move away from the harassment. It’s obvious that the penguin exhibit falls very short in meeting the needs of these animals.”

By mid-April, the zoo said Gomez was being integrated into the main population again. On Thursday, zoo officials once again shut down the camera as a result, they said, of the Twitter user.

忘れた事は一度もない2022年3月

昼も夜も毎日襲われ続け死んでしまう…と泣きながら見てた

All year long, this penguin has been subjected to such terrible bullying.

The zoo has ignored my pleas to the zoo to help a penguin that is being bullied.#KansasCity #KansasCityZoo #ペンギン pic.twitter.com/1lkgHaU5dR— ペンギンちゃん (@ariel_digit) March 13, 2023

Putney said the short video clips are being taken out of context.

“It has potential certainly for a huge uproar when the reality is, that animal and those animals, are having a great life, and they’re not passing on the whole story,” Putney said. “To me, it’s really a lie.”

Conservation and the case for zoos

A few decades ago, zoos were mostly about entertainment. In places like Kansas City, that’s changed.

In 2014, the KC zoo started building its conservation strategic plan. The initial document, released in July 2015, read: “Zoos need to be engaged in local, national and international communities to inspire citizens to conservation action. The Zoo should strive to be THE conservation advocate in the Kansas City region.”

That initial conservation plan had three goals: Influence others, protect species and conserve resources.

“We still want a zoo setting to be fun, but we’ve really evolved, and now it’s just as much about education and conservation,” Putney told a group of high school students during a virtual career week in 2020. “We want the animals to be the hook when people come in, but we want them to leave with a conservation message and we want people to understand what the needs are out there in the environment.”

It’s a crucial environment to study and preserve.

Heather Lynch, a professor of ecology and evolution at Stony Brook University, visited KC’s penguin exhibit once, years ago, to help conduct research on dialects in penguin colonies in captivity. She calls the exhibit pretty typical.

She remembered one bird in particular: a “one-legged, blind, yellow-eyed” penguin, a nod to the kinds of “oddballs” she said are often off-loaded on new exhibits from other facilities, who aren’t likely to loan out their “Secretariat.”

Lynch, who has long studied the relationship between Antarctic seabirds and climate change, sees penguins as the canary in a coalmine to alert scientists to the overall health of our planet and oceans.

This is part of the thinking behind the Kansas City Zoo’s decision in 2015 to donate 25 cents from each admissions ticket to conservation efforts, including to help Humboldt penguins in Peru, where Putney has traveled a few times to help conduct research and conservation efforts.

But is it enough? Lynch isn’t sure.

A decade ago the KC zoo was putting about $50,000 a year toward conservation. Last year they donated nearly $430,000.

“If you’re going to build a big exhibit, putting that money directly into conservation would certainly be more efficient, let’s put it that way, than building a big exhibit of captive penguins, and then on the side, sort of raising money for conservation,” Lynch said. “It’s not like that money doesn’t probably do good, but it’s kind of an inefficient means if the goal is to conserve penguins.”

Lynch said the increasingly complicated question of zoos’ existence and the purpose of keeping animals in captivity is nuanced, especially when tied to conservation dollars.

“When money is being raised for conservation, is that sort of just window dressing, is it just green-washing what’s kind of an otherwise potentially cruel situation, certainly when you see penguins in the wild and they travel thousands of miles in the winter?” Lynch said.

Putney takes offense to any insinuations that the Kansas City Zoo doesn’t care enough about its animals and their well-being. For many zoo-goers, especially children, who’ve never seen the ocean, let alone penguins in the wild, the exhibit might be their most meaningful exposure to the creatures, he said.

“We want people to fall in love with the birds when they’re here so they care about the animals and want to be conservationists as they grow older,” Putney said. “But it has to be fun. If it’s not fun, then people aren’t going to come back and we lose the opportunity to get (the penguins’) message across.”