Black America’s Fight for Yusuf Hawkins Is Far From Over

I dare you to examine the 1989 murder of Yusuf Hawkins and tell me America has changed. Yusuf Hawkins was a 16-year-old Black teenager who, along with three friends, went to Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, one summer night to look at a used car his buddy Troy had found for sale in the newspaper. Yusuf didn’t know anyone in Bensonhurst, but he and his friends found themselves surrounded by a mob of 30 young white men swinging baseball bats, wielding handguns, and accusing them of not belonging in their all-white neighborhood. The mostly Italian men forced themselves between Yusuf and his friends, pinned Yusuf up against a dark doorway, and shot him to the ground. Yusuf stood up quickly as his attackers fled. He even managed to take a step toward his friends, not knowing, of course, that two of the shooter’s bullets had blown his heart wide open.

“We’re not racist. We just don’t like Black people,” a young man from Bensonhurst proclaimed on camera just days after Yusuf’s murder—and moments after a young Reverend Al Sharpton led a march of hundreds of Black people directly through the neighborhood. This particular young man stood with the white counter-protesters, some of whom threw watermelons and soda at Yusuf’s grieving family members and shouted, “N---ers, go home!”

Today, one could cite racial sensitivity in white communities as a sign of change and progress. But there were white people—Italians too—supporting Yusuf’s family, and marching through Bensonhurst in ‘89. Today, one could call out the increased diversity of races in Bensonhurst as evidence of progress. But de facto segregation in New York City is as prevalent today as it was the day Yusuf was killed. Many white Bensonhurst residents simply migrated to all-white neighborhoods in Staten Island, as the Asian population in Bensonhurst increased before their eyes. My ancestors say, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” I say there is an equal and opposite arc of immorality. It bends toward injustice by way of denial at any cost and it is incumbent upon us willing to tear that arc to pieces.

What followed Yusuf’s murder was one of the most racially charged uprisings New York City has ever seen. “White Gang Kills Black,” read the Daily News headline in ‘89. Today, that headline is fitting for the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia. It is fitting for the gang of police who murdered Breonna Taylor in Kentucky. Unfortunately, an equally apt headline for then and now is: “Extraordinary Measures Required for Justice If Black.”

The McMichaels (two white men), Arbery’s alleged killers, were not arrested until 74 days after the murder took place—and only after leaked footage surfaced of the crime, which led to public outcry. Within that 74-day span George E. Barnhill, the local district attorney, claimed Arbery “initiated the fight,” an absurd assertion that would have been effective had the footage not leaked. It has been 168 days since Breonna Taylor was murdered by police in her sleep—and no charges have been filed. A nearly blank police report about the incident is denial in black and white; an obstruction of justice enacted by those who are paid and elected to serve justice.

The Tragedy of Yusuf Hawkins: A Black Teenager Slaughtered by a White Mob in 1980s Brooklyn

When Black people are victims of racist crimes and our elected prosecutors don’t take action, little recourse remains for those who want justice. Violence is not an option. As we’ve seen, uprisings—like those in response to the murder of George Floyd and delays in charging any of the officers involved—perversely become social discourse about how Black people shouldn’t be “rioting.” Attempts to change the laws nationally are stifled by deflection, as we saw when the subject of police protection took the spotlight at the June 10th House Judiciary Committee Hearing on police reform. City mayors are no help, as they cower to the needs of their most wealthy constituents who are most likely not Black, and who are all too often silent, convinced the victim is at fault, afraid of the “Black Lives Matter” mantra, or so desperate to believe their communities are not racist they’ll turn a blind eye to almost anything. All of this amounts to roadblocks wrought with denial that racist murders take place in modern times. That leaves victims of racist violence little choice but to march.

The Hawkins family faced similar challenges after Yusuf’s murder. The nearly 30 young men who attacked Yusuf immediately went into hiding and their Bensonhurst community protected most of them, including the alleged shooter. Would-be allies rationalized the murder by accepting the widespread narrative that Yusuf was in the middle of a love triangle with one of the attackers and his white girlfriend, a story seemingly more palatable than the reality that Yusuf was killed for being Black in the wrong part of town.

Trevor Noah Goes Off on Kenosha Police for Treating Vigilante Better Than Jacob Blake

Luckily for Yusuf, he wasn’t on drugs, he didn’t have a criminal record, he wasn’t dating a white girl, and none of his attackers were police officers. Notwithstanding the fact that those factors shouldn’t matter, an additional obstacle was NYC’s Mayor Ed Koch, who had a reputation for not being sensitive to the needs of the Black community. Koch shut down Sydenham Hospital in the Bronx despite protests and its significance to Black citizens. Under Koch’s reign, Willie Turks, a Black transit worker, was chased to his death by a white mob. Michael Stewart was beaten to death by NYPD police officers, Eleanor Bumpurs was shot to death by NYPD officers, Michael Griffith was chased to death by a white mob in Queens, and the Exonerated Five were falsely arrested and eventually imprisoned for a rape they didn’t commit. I don’t suggest a mayor is responsible for the crimes in their city. But I do believe leaders who aggressively address racism can help save Black lives, and when they don’t they’re contributing to the problem.

With an equal and opposite arc of immorality in play, bending away from justice, it would stand to reason that what was a roadblock when Yusuf was murdered will be a roadblock now, and what was effective in the wake of Yusuf’s murder will be effective now.

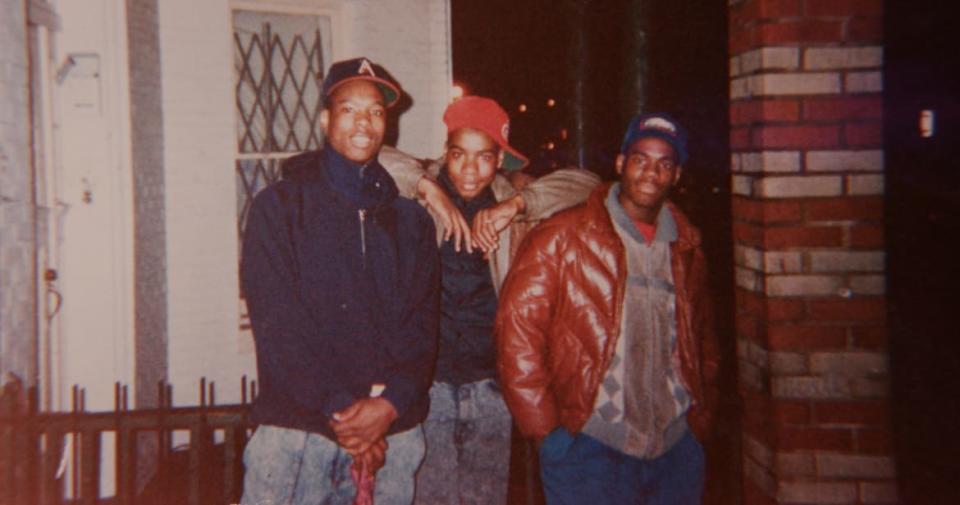

Yusuf Hawkins (L) and his buddies

Persistence and proximity—tried, true, and virtuous elements of effective activism—brought Bensonhurst to its knees. Rev. Sharpton and the Hawkins family executed dozens of marches between August ‘89 and January ‘91 directly through Bensonhurst. Their actions disrupted businesses in the area (decreasing their bottom lines) and frustrated residents who didn't want to be “bothered or financially hurt” by the presence of the protesters. That continued pressure, right in the heart of their neighborhood, compelled Bensonhurst residents to turn Yusuf’s attackers in.

Had Rev. Sharpton led marches through Manhattan, Bensonhurst residents wouldn’t have felt the discomfort. Had the marches been for just a day or a week, they wouldn’t have been as effective. New York City and America have not changed. So, I suspect, continued protests and marches through the neighborhoods of today’s racist killers will make a difference today.

“I urge that people not engage in marches into communities and the reason is the community thinks it then is the perpetrator of the violence, and I don’t think that any community can be branded that way,” said Koch in response to the Bensonhurst marches. Yusuf was murdered just weeks before a pivotal mayoral primary between Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins (a Black man) and Mayor Ed Koch (a white man). Neither took a tough stand against their city’s racism and perhaps neither could afford to.

As we approach November’s election, I keep in mind that if a community that teaches racism is told it is not to blame for the resulting racist violence, then the community will dig in its heels and refuse to change. A community under the wrong leadership will attack those who accuse it of being racist, all while it continues to turn a blind eye to the racist murders in its streets. To that end, pressure must also be directed against politicians who pander to their bases at the expense of racial progress. That pressure should be applied at the polls. NYC residents ousted three-term Mayor Koch, some say, as a result of how he responded to Yusuf’s murder. I’m hoping voters across the nation apply that same reasoning this year.

With the constant blowback that comes with calling out racism, on a neighborhood and national level, it’d be easy to think that all Black people can effectively do in the face of the willfully ignorant is lay the bodies of our murdered loved ones at the feet of our oppressors and hope the smell of our carcasses compels them to move. But, no, it’s the sound of our voices outside their shops, the presence of our Black skin on their lawns, and our tenacity that is our ace in the hole.

America has not changed—and what brave Americans can do to seize justice hasn’t either. It’s up to us, as it always will be, to get up close and intimate with racist killers and apply persistent (nonviolent) pressure. Pressure at the polls, and pressure in our neighborhoods. The Hawkins family deserved that in ‘89 and our loved ones deserve it today.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.