Black blood donors are desperately needed, so I donated for the first time

Don’t faint, don’t faint.

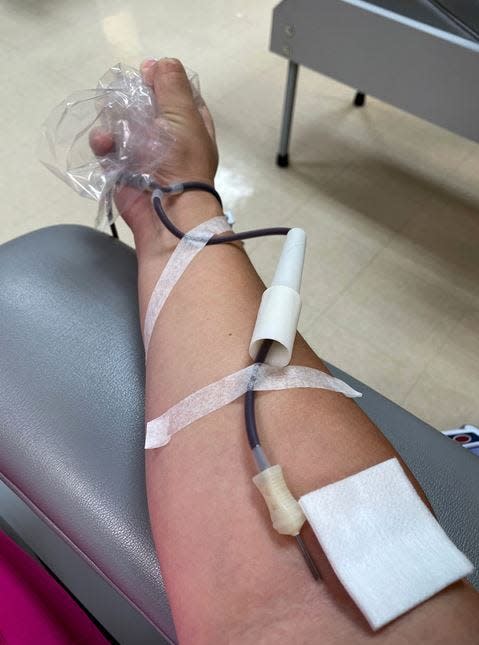

I mentally repeat the words with each squeeze of the stress ball, willing myself to remain conscious. The phlebotomist has tried to ensure that I do: propped up my feet, cradled an ice pack behind my neck, gave me a can of Coke (which, in my reclined position, I spilled down my shirt).

The tangle of tubes stemming from a needle in the crook of my right arm darkens. Presumably, clinical machinery beeps and whirs, but I’m too focused on not passing out to listen.

► ‘I’ve never seen it this bad’: Blood banks nationwide plead for donations

I brace myself for the tingling, the slowed heart rate, the vertigo, the nausea. And worst of all, the tunnel vision. The last time I fainted, I regained consciousness on a concrete pool deck, concussed, to the sound of faraway sirens I knew were blaring for me.

Needles and blood don’t bother me; I’ve just been a fainter since I was a little girl. It’s why I’ve never donated blood before today.

Suddenly the needle is out, a bandage in its place.

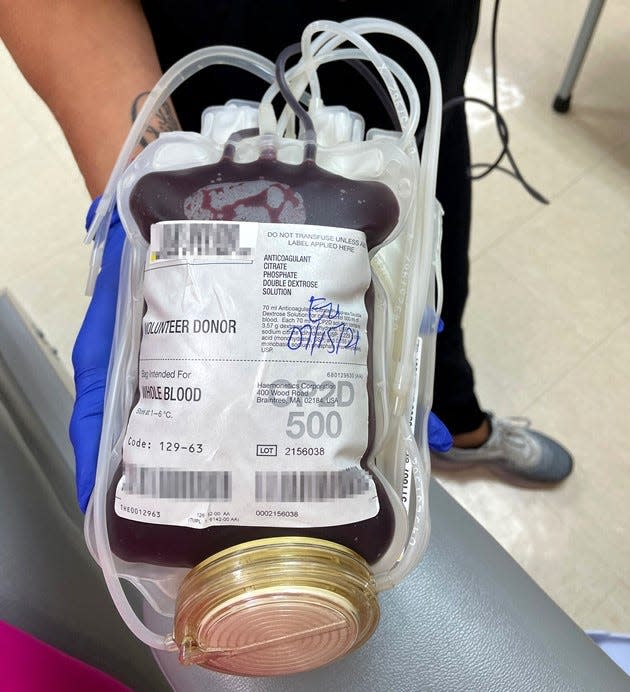

“You want to hold it?” asks Michelle Santiago, my phlebotomist at the OneBlood donor center in Stuart, as though I’ve given birth.

She hands me the thick, plastic pouch, containing a pint of my blood. Still warm. Such a dark red, it’s almost black. It is Black, because I am — half anyway.

That’s why I’m here.

95% of Black Americans don’t donate blood

There aren’t enough donors of African descent in the U.S.

Just 5% give blood, reports OneBlood, a nonprofit that supplies blood to over 200 hospitals in Florida and parts of Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas.

A host of reasons may fuel the problem, according to a 2018 literature review by Georgia State University researchers Ashley Singleton and Regena Spratling.

“Increasing [Black] blood donations is complex,” they wrote in the journal Health Promotion Practice. “Barriers such as donor ineligibility; deferment rates due to low hemoglobin; poor experiences with blood donation ... and mistrust of medical providers all raise substantial hurdles.”

► ‘Severe blood shortage’: A whole-blood donation can save up to 3 lives

► Pandemic donation: Yes, it's safe to give blood during COVID

Retaining minority donors is just as difficult.

“Experienced donors need to be continuously reminded that blood donations are needed,” they wrote. “Blood donations are often low on priority lists.”

The American Red Cross announced a severe national blood shortage June 14, World Blood Donor Day. As COVID-19 restrictions waned, trauma cases, elective surgeries and organ transplants spiked, the organization said.

The country’s blood supply remained “dangerously low” as of Sept. 29, when the Red Cross said the delta coronavirus variant was responsible for an abnormal decline in donors.

While the shortage may be temporary, the need for a more diverse array of donors is constant, said OneBlood spokesperson Susan Forbes.

“Over 70% of the blood supply is Caucasian … it’s one of the major issues facing the blood industry,” she said. “When you live in a diverse nation, you need the blood supply to match the patient population.”

America needs a diverse blood supply

You’ve heard it before: “We all bleed the same color.” When a person of color requires a blood transfusion, however, a donor’s race and ethnicity matter.

Everyone is born with one of eight blood types: A+, A-, B+, B-, AB+, AB-, O+ or O-.

The letter indicates whether what’s called the A and B antigens appear on red cells. The plus or minus sign denotes the presence or absence of a protein known as the Rh factor.

A person with O+ blood, for example, has neither antigen but is Rh-positive.

“People may think, ‘Why do you need a diverse blood supply? If someone gets the right blood type, isn’t that all that matters?’ ” Forbes said. “But it’s actually more than that.”

A and B aren't the only antigens that configure a person’s blood profile. There are over 600, some of which are found only among certain racial and ethnic groups, according to the Red Cross.

Such advances in genetic testing mean patients may receive more precisely matched — and potentially more successful — blood transfusions, said Deborah Cragun, director of genetic counseling at the University of South Florida College of Public Health.

“It’s not saying that people who are white can never match with a Black individual,” Cragun explained. “Statistically, it’s more likely [they’ll] find a match the closer they are with their ancestry.”

There’s a 50% chance that a Black, type O donor is a match to someone with sickle cell disease (SCD), the most common inherited blood disorder, according to OneBlood. That probability drops to less than 3% among type O donors of other races.

When the body detects a foreign antigen in the blood, it develops antibodies to attack it. That’s why closely matched blood is crucial for people who require frequent transfusions, such as those with SCD.

“This helps prevent the buildup of antibodies,” Forbes said. “The more antibodies you create, the harder it becomes to find a compatible unit of blood.”

‘Your blood’s not whole’ with sickle cell disease

DeMitrious Wyant, of Orlando, has lost count of how many hundreds of blood transfusions he’s received in his 34 years. His body knows the pulse of foreign blood in its veins.

“The treatment is so severe,” he said. “When you’re getting an exchange transfusion … you can tell that you’re being stripped of blood and getting different blood put in.”

Wyant, a chef at Your Best Taste Catering, was diagnosed with SCD at 2 months old. His mother took her wailing, feverish son to the hospital multiple times before doctors discovered misshapen red blood cells were the cause of so much pain.

Red blood cells, normally round, contain hemoglobin, which ferries oxygen throughout the body. They account for up to 45% of blood volume and live up to 120 days.

A person born with SCD has red blood cells that are C-shaped — resembling a farming tool called a sickle — and can be rigid and sticky. A cluster of sickled cells can hamper blood flow and cause extreme pain and other serious problems, such as stroke or infection. These cells may live as few as 10 days, according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

“Your blood’s not pure, your blood’s not whole,” Wyant said.

Anyone may be born with SCD, but in the U.S., the disease is most prevalent among people of African ancestry, like Wyant. About one in 365 Black Americans and one in 16,300 Hispanic Americans is born with the disorder, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The only known cure is a stem cell or bone marrow transplant, which the agency notes poses serious risks. SCD patients rely on transfusions from healthy donors to replace their short-lived red blood cells.

“You have to screen the blood supply to find a match for them,” Forbes said. “It really is a fascinating effort that takes place that most people aren’t aware of.”

Wyant was in poor health until about three years ago; he endured bouts of pain known as sickle cell crises every few weeks.

He’s since established a regimen he says has meant fewer hospital visits: light exercise, healthier diet, and natural remedies instead of Western medicines when possible. He joked that his daily beet smoothie is the new blood transfusion, and shares what’s worked for him in his podcast, “The Souljah Strong Way.”

“You can live well with sickle cell,” he told the USA Today Network–Florida. “I’m living proof of that.”

Still, transfusions are an eventuality for people with SCD and other blood disorders.

Wyant said he’s had so many that antibodies from different races and ethnicities flow through his blood. With each transfusion, finding a match is increasingly difficult.

“A lot of Black people, they don’t really fool with the health care system,” Wyant said, acknowledging the nation’s history of using them as medical guinea pigs. “[I’ve] started making it my business to get more people of African descent to start donating blood.”

Blood donation comes full circle

When I left the donor center that July afternoon, I felt pride and regret.

I’d overcome my fear of fainting and by donating whole blood — which gets separated into red cells, platelets and plasma — saved up to three lives.

How many more could I have helped since reaching the donor age of 16, which was 17 years ago?

It took learning I was among the 95% of Black Americans who don’t give blood for me to act.

Three weeks later, OneBlood notified me that my donation was en route to a South Florida hospital group. The hospital where I’d had a spinal fusion the summer before was part of it.

I recalled consenting to a transfusion if needed during surgery. I didn’t require one, but now realize I’d expected an ample blood supply would be at my disposal. The people who had given a piece of themselves for my benefit never crossed my mind.

I’m glad I could return the favor.

Lindsey Leake is TCPalm's health, welfare, and social justice reporter. She has a master's in journalism and digital storytelling from American University, a bachelor's from Princeton and is a science writing graduate student at Johns Hopkins. Follow her on Twitter @NewsyLindsey, Facebook @LindseyMLeake and Instagram @newsylindsey. Call her at 772-529-5378 or email her at lindsey.leake@tcpalm.com.

This article originally appeared on Treasure Coast Newspapers: Give blood today: OneBlood, Red Cross need Black, Hispanic donations