Opinion: Can a Black Democrat win Mississippi's Senate race?

Growing up Black in Stone Mountain, Ga., I was used to certain routines. Church on Sundays always went past 1 p.m., sweet tea was always too sweet and white people had a monopoly on the highest offices.

Of course, Black lawmakers served in the state Legislature and local government. But when it came to statewide races, white Republicans dominated. This puzzled a kid like me who grew up in Black suburbia. Everyone around me looked like me. But those in the upper echelon of power largely did not. I assumed this was the way it would always be in the South — home to half of Black America, according to the last census.

But after moving here to Washington, I noticed signs of change.

Not only were the Florida and Georgia gubernatorial races two years ago competitive, but they featured two Black candidates, Andrew Gillum and Stacey Abrams, who very nearly won. In this year's Senate races in South Carolina and Mississippi, Black Democratic challengers are posing surprisingly competitive challenges to white Republican incumbents.

South Carolina currently has a Black senator, Tim Scott, a conservative Republican. But Mississippi hasn't had one since shortly after the Reconstruction era.

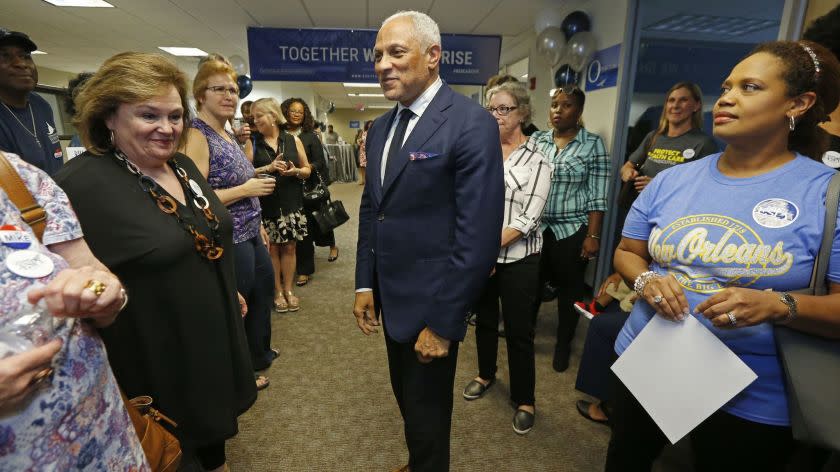

In the Magnolia State, Mike Espy, a Democrat and former U.S. representative and U.S. secretary of agriculture, is running against the Republican incumbent, Cindy Hyde-Smith, a former state lawmaker and commissioner of agriculture and commerce and the first woman to represent Mississippi in the U.S. Senate.

The Tyson Group recently polled Mississippians and found Hyde-Smith was just one point ahead of Espy. Eighteen percent of voters polled were undecided.

When I talked with Espy this week, he acknowledged that it's extremely hard for a Black politician to win statewide office in Mississippi, even though Black people make up more than one-third of the population. He said that internal polls show the race tightening, but expressed frustration that the Democratic establishment has been slow to embrace his candidacy, previously choosing to spend precious dollars in other races that are perceived to be closer.

But Nathan Shrader, a political scientist at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss., is skeptical that Espy could win.

Yes, this race is competitive, which he acknowledged is unusual in a state such as Mississippi. History has shown that Black politicians don't win statewide races. (The last Black senator left office just after Reconstruction, when federal forces pulled out of the state and local white authorities suppressed the voting rights of recently enfranchised former slaves.) And, as Shrader pointed out, Espy is running in a state where Trump is deeply popular. (He's up 10 points over his opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden.)

Hyde-Smith at first glance seems to be a shoo-in, given that she is extremely loyal to Trump. She was initially appointed in 2018 to fill the seat of Thad Cochran, who was in poor health and died the following year. And during her tenure, she's voted in line with the president's positions 94.5% of the time. In the 2018 special election to fill the remainder of Cochran's term, Trump wasn't on the ballot. Hyde-Smith defeated Espy, capturing nearly 54% of the vote, but that was by a narrower margin than another Senate race that year, in which Roger Wicker, the Republican, handily defeated David Baria, the Democratic challenger, with nearly 59% of the vote.

In this year's rematch, Trump is on the ballot, and that's an advantage for Hyde-Smith.

"It really is a coattails kind of thing," Shrader told me. "With Trump on the ballot, an Espy victory will be very hard."

Very hard, but perhaps not impossible. Espy has made history before, as the first Black Mississippian elected to Congress since the 19th century. And, he is charismatic and his arguments about healthcare have resonated given the COVID-19 pandemic.

Espy is personable, and in campaign events via Zoom and social media he has talked animatedly about issues such as the closure of rural hospitals and the lack of access to affordable healthcare. Espy is also quite popular among women. The Tyson Group poll gave Espy a seven-point lead with female voters and Hyde-Smith a 10-point lead with male voters.

For a woman such as Laurie Bertram Roberts, a 42-year-old local activist and Jackson resident, Espy's stance on abortion rights is intriguing.

"I appreciate he isn't out here blowing the pro-choice horn," Roberts told me. "That's not normal for Mississippi."

Espy told me that while he's personally opposed to abortion — except in cases of rape or incest — "Roe versus Wade is the settled law of the land. I believe a woman should have the right to make a decision about her own body," he said.

For Roberts, Hyde-Smith has repeatedly embarrassed her home state. She's anti-abortion and backed the appointment of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, she said.

Then there was the time she made headlines for saying that if one of her supporters "invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row." And an old photo of her posing in a Confederate hat surfaced, for which she was roundly criticized.

Hyde-Smith's campaign, which did not respond to a request for comment, has beefed up advertising in the wake of that election.

Henry Barbour, who represents Mississippi on the Republican National Committee, acknowledged that nationally, Hyde-Smith is known for those two gaffes and being a Trump loyalist.

"The reality is, she's a good lady," he told me, "fighting hard and doing what she needs to do.

"Most people in Mississippi are looking for someone who votes for Trump. People down here tend to be pro-life and they're uncomfortable with the national Democratic Party," he said. Barbour said that Democratic immigration policies also make many Mississippians uncomfortable.

"Those are things that make it harder for people to vote for Mike Espy," he said. "Though a lot of Mississippians respect and like him fine personally, they're not crazy about his politics and who he would empower in Washington.

"A vote for Mike Espy is a vote for Chuck Schumer to be in authority in the U.S. Senate. A vote for Cindy Hyde-Smith empowers Trump."

Democratic leaders haven't paid much attention to this race until recently, Espy laments.

It has been more than a century since a Black represented the state in Washington, even though there were several instances in the past century when white Mississippians were a minority. Those were decades, of course, in which white people controlled the state via Jim Crow terror, disenfranchisement of Black voters and racist policies promoted by segregationists like James O. Eastland.

But Espy pointed out that in Mississippi, it should be easier for Democrats to win elections because of how many Black voters live here.

"I want votes from everyone," he said. "I'm the candidate who wants votes from everyone irrespective of race. But you have to look and see historically where those votes will come from.

"Because our Black population is so large, our campaign has a lower threshold for white voters," he added. Espy will need record turnout from Black voters to win.

"There's been a legacy of disinvestment of those in Washington who now believe a Black man can't win," he said. Espy believes that if the national party put more money "into political organizations to build infrastructure, we would already have a Democratic senator and governor."

An Espy victory could mean a great deal to many in the state.

Jarvis Dortch, a 39-year-old Black former state lawmaker and executive director of the Mississippi ACLU, told me an Espy victory "would change our politics and improve our state."

"We have one party that feels like they can win no matter what and it makes them cater to their base. Unfortunately, that means they aren't taking issues like poverty and healthcare seriously," he said. "Making this a more competitive state would mean we get better results out of our senators, state Legislature and governor."

When I talked to Barbour, the Republican committee member, he noted that Democrats and his party earlier this year "joined forces" in the Legislature to change the state flag. Both parties overwhelmingly agreed to let voters select a new flag that may not include the Confederate battle emblem but must include the phrase "In God We Trust."

"It was a great effort of bipartisanship," he told me. "Both sides deserve a lot of credit. It was long overdue."

For Bill Chandler, executive director of the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance, Espy's victory would mean a powerful ally with substantial influence.

"Mike has been a good ally of ours in the community," Chandler told me. "He's worked with worker's compensation cases."

And for my Aunt Daisy Ware, who hails from Okolona, Miss., having a Black person in that position would be substantial progress. When she lived in Mississippi, voting was a foreign idea. No one in our family, as far as she knew, was able to cast a ballot until the 1980s.

"They were trying to keep people from voting. Especially Black people," she told me. "Black people are so important. If we weren't important, why would they try to keep us from voting?"

So when she sees Black politicians such as former President Obama and Espy, it's an opportunity to consider electing someone who looks like her.

"That's exciting for the Black race, I think," she told me. "That means we have come a long way. There have always been Black people running for different positions, but they didn't have the opportunity because we couldn't vote."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.