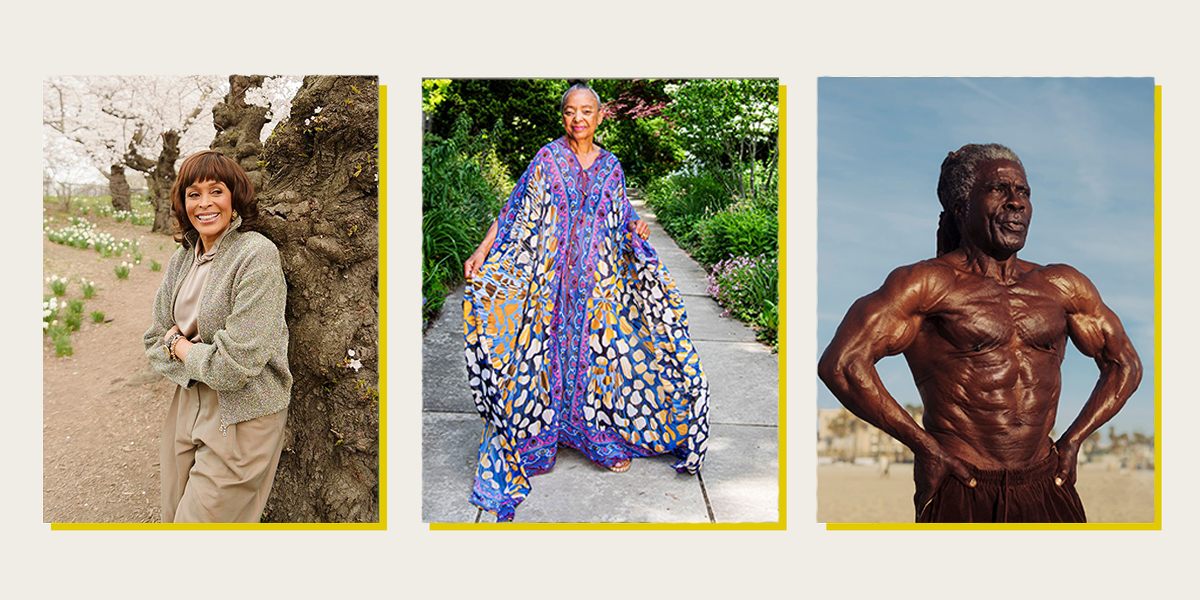

Black Elders Share Their Life Lessons With the Next Generation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For too long, too many stories of what it means to be Black in America—and what it feels like—have gone untold. After this year of racial reckonings and, we hope, awakenings, we are proud to present LIFT EVERY VOICE, a collection of powerful interviews with the oldest generation of Black Americans about their lives, their experiences, and the wisdom that can carry us to a better future.

Lift Every Voice brings together the wisdom of more than 50 subjects from around the United States. Our interviews were conducted by a brilliant team of young Black journalists, many from historically Black colleges and universities. The beautiful portraits were created by the next generation of Black photographers.

These five profiles are just a few from the larger collection, which can be found at oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice.

Dorothy Butler Gilliam, Pioneering Black Reporter, on Racism in the Newsroom and the Power of Stories

83, JOURNALIST, WASHINGTON D.C.

In 1961, Dorothy Butler Gilliam became the first Black female reporter at The Washington Post, where she went on to become a legendary writer, editor, and columnist.

Kenia Mazariegos: An ice-breaker: What is your biggest pet peeve?

Dorothy Gilliam: One pet peeve would be people who only talk about themselves. Somehow, when people talk about themselves it just feels…small.

KM: You were in your late twenties when Jim Crow ended, so you experienced it firsthand—the depression, the discrimination, the unfairness of treatment. What was it like growing up around that time?

DG: I am who I am because somebody loved me. People in my family, my church, my community. And even though Jim Crow had all hell breaking around us, because of our love and care for each other and the way we conducted our lives—which is very much in the Black tradition—we were able to live a life that gave us strength, that gave us meaning, that gave us a way to be helpful to others. A way to really know that we were not what white people in the Jim Crow South—I guess we’d have to say white supremacist South, even then—we weren’t who they said we were.

KM: Is there a moment in time during your childhood that you realized that you needed to be tough, that this wasn’t going to be easy for you or your family?

DG: As young people, we would be walking to school and white kids would throw rocks at us. Our teachers and our families said, “Don’t fight back, we will not be the kind of people they are.” Not fighting back was tough. But in the end, we feel very much that it was the right way to go because with all that happened, we still just never became haters, even though we knew that our schools were getting the used books and the white kids were getting the new books, and there were just so many obvious discrepancies.

We had a sense of dignity and purpose. My father was a minister. He was a leader in our community. My mother had trained as a teacher but when they moved from the country, where she could teach, to the city, she did not have the credentials that were required. So she worked as a domestic. And as much as I resented that she had to do that, and as much as I’m sure it was difficult for her to be trained as a teacher but to have the only job open to her be a domestic, she was a person who would never let anything destroy her dignity.

I recall where people would call her to come and work for them and they would say, “May I speak to Jesse?” And I would say, “Do you mean Mrs. Butler?” And my mother would say, “Give me the phone Dorothy!” And then, “Hello, this is Jesse.” That always hurt me, but her sense of self and her dignity was much more than what was required.

KM: It must have been easy for some people, during that time, to give up—to not achieve. At what point did you know that you weren’t going to stick to societal norms and that you would pursue journalism?

DG: I was about 17. I was a freshman at Ursuline College, a Catholic women’s college. I got a job at the Black newspaper in Louisville, the Defender, as a secretary. I had been learning to type, and take shorthand, and all those things. And one day the editor came in and he said, “I’m going to send you out to cover a society story because the society editor is sick.”

I was surprised and, certainly, I had never been introduced or exposed to Louisville Black society, but when I began doing that I was able to see that there were so many different worlds. This was a different world—the Black middle class, who had Waterford china, and beautiful dishes, and things that my family didn’t have. It was my ability to see that journalism could open and expose me to new and different worlds that really pushed me into the profession.

I decided I really wanted to train to be a journalist, and I was able, after the first two years, to go to Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri—but at each step, the white supremacy was just always pushing hard against us and all of us. For example, the school I wanted to go to at first was the University of Missouri at Columbia, Missouri, and it turned out that every time a Black woman tried to get into that school, they would find a way to push and not let her enter the school. I ended up saying, I will go where I know I’m wanted! And that was Lincoln University.

I wanted to be able to write stories for the mainstream press that would really show the diversity among the Black community and to show who we were. I mean, when I first arrived at The Washington Post, I overheard one of the old-time editors say, “We don’t even cover Black deaths because they’re just cheap deaths.” To hear that kind of horrible statement coming from a newspaper editor is a good example of how deep this whole system was in American society.

KM: What was happening at the moment you first stepped into The Washington Post as the first Black reporter?

DG: I felt fear and apprehension. When I first walked in that newsroom, I recalled one of my professors at Columbia, where I had finished graduate school, saying, “You have a double whammy. You are going to have a tougher time both for your race and for your gender.” So, that’s saying that my personhood—you know, separate from what I could do, just my very personhood—was going to be challenging in this industry. Yeah, emotions were—as I said in my book, Trailblazer, I felt like I was jumping into a rapidly moving ocean, and I had to jump in with a lot of white men who were seriously anxious to hold on to their power.

KM: You covered the racial integration at the University of Mississippi, where James Meredith was denied admission for being Black. What was that like?

DG: It was frightening. Mississippi’s segregation was so deep. It was a lynching state. I mean, it was a state where Blacks were routinely strung up in trees, and wherein they’d have a lynching and people would come from all over to see it. They’d show the hanging Black body to children. So Mississippi was very angry that James Meredith had the great will to integrate the University of Mississippi because it was a bastion of white supremacy.

I ended up sleeping in a funeral home because there were no hotels for Black people to sleep in. Sleeping with the dead was not an experience that I remember cheerfully, but I was glad to have a place to sleep—and, certainly, nobody bothered me.

The other thing I remember is just the bravery of the people, the courage of the people. I interviewed so many people in the community, and they were filled with fear, yes, but with hope. “My goodness,” they said. “It actually happened! Somebody actually integrated that University of Mississippi.” But then when I went to interview Medgar Evers, it was just startling, his courage, because he said—despite all that was going on, when I left Oxford with the troops, with the Ku Klux Klan walking around with guns being displayed, with all these fanatics from all over the country who came to protest that, you know, the federals were taking over. It happened. Medgar Evers at that point was the NAACP field secretary and when I interviewed him, he said, “Oh, we’re not finished.” He said, “This is just a first step. We’re going to be integrating, you know, all the state colleges.” Blacks were paying taxes that helped to support these institutions, they just were unable to enter them. So, he said, “Our goal is to integrate all of these schools,” and when I heard him say that I thought, What courage!

Seven or eight months after I interviewed Medgar Evers, he was assassinated outside of his house, and what they would say is that this is the price our people had to pay for freedom. And part of it comes from, in the case of Medgar Evers, his love for Black people, his knowledge that things had to change, and his willingness to do what had to be done. He was not naïve thinking that perhaps nothing might happen to him. He knew that, you know, he was being constantly hunted down.

KM: Did his death contribute to your work in activism?

DG: I don’t think it directly did, but I do know that part of my deep desire was to try to make journalism a profession—and I’m talking about daily newspapers then, of course, you know, things have changed tremendously now—but to try to make journalism a place where we could talk about the reality of America. Where there’d be enough people of color to share honestly and to write the stories that displayed the reality of what was going on. One of the things that kept me at the Post for so long was that I was able to begin writing a column in which I could really share my opinion of what was going on, and then I worked as an editor where I could hire reporters who could come in and could write articles about what was happening in the communities from a deep and informed perspective.

KM: Are you happy with what’s going on in the newsroom now, that there’s more diversity, that Black women are able to wear their natural hair on camera?

DG: Yes, even the changes that have happened in the last year, especially after the death of George Floyd and the pandemic, Black Lives Matter—those changes have been very positive. I also want to acknowledge the changes that have been made. I’m happy, for example, that The Washington Post has hired an African American woman as the managing editor for diversity. But I still feel that there’s so much work to be done.

KM: What would you tell a new journalist who’s trying to break into the journalism field, someone who just graduated from school?

DG: Well, I do still mentor people, and there’s a young man I mentor who is not just breaking in, he’s been in a while, but it’s still important to bring all of the necessary skills, and it’s important to bring a level of courage, in terms of writing about subjects that may not feel so comfortable in the newsroom. You’ve got to really understand how to do your work, to do it well, to do it quickly, but you also have to be willing to take some chances and push to do some articles that may not be popular.

I remember when I was writing columns, it got very uncomfortable because I was saying things that they didn’t want to hear, or they didn’t want to print, but they did print them. As a matter of fact, I’m currently compiling a book of columns that I wrote in the '80s and '90s, and part of my wish is to show their relevance to today.

One of the things I did when I was president of the National Association of Black Journalists, I interviewed a lot of the journalists to see how they were feeling, and they were stating that the white editors were very resistant to a lot of their story ideas. I’ve seen the same thing on college campuses. When I was working at George Washington University—I started a program for young people called Prime Movers’ Media—the GW students would come to me and they’d say, “I don’t want to work on the college newspaper because these white editors continue to say ‘That’s not a good story, nobody cares about that." So, it’s really important for editors to have a more open mind, and to understand the importance of diversity, and to write stories about what’s really happening.

I think the media failed terribly during the Trump-era when they gave so much attention to Trump when there were so many other stories that needed to be written, and I hope that there will continue to be a more open-minded attitude on the part of media. People are going to have to change their way of thinking.

Interview by Kenia Mazariegos. Photograph by Michael A. McCoy.

At 75, Legendary Bodybuilder Robby Robinson Is Only Getting Stronger

BODYBUILDER, 75, VENICE BEACH, CA

When Robby Robinson started bodybuilding at Venice Beach’s Gold’s Gym in 1975, he remembers being told, “Blacks don’t get contracts” to compete. He was harassed at competitions and struggled with steroids and sickle cell anemia. Despite many wins, Robinson never captured the IFBB’s overall title, Mr. Olympia. After he complained about mistreatment, the IFBB suspended him and he moved overseas to compete without the fear of racism. He’d eventually return to the U.S. in 1994, winning the first ever Mr. Olympia Masters, for athletes over 50, en route to three such titles. Today, at age 75, Robinson still lifts, and he shares how he forged the strength to face any challenge.

MAKING THE LEAP

I went to what was basically an all-Black high school in Tallahassee, Florida, so I really didn’t encounter that much racism. Because everybody was poor, Blacks and whites, it didn’t look like I was any better than you—we ate the same food, cooked in the same pots. So I didn’t really get the blunt force of it, I guess, until I left the swamps. I never heard the word n***** until I came to California in '75. When I left the swamps, I realized, Wow, life is gonna be hard out there. That’s how I dealt with it.

BLOCKING OUT BIAS

I was doing well because I had just a great body. I mean, that’s just the hard-core facts. I had a great physique; I had a good, tough mindset. So I just didn’t listen to all the negs. I think when you get caught up in the negs and just keep listening to it, it drains your ability to do whatever you want to do positive. I just didn’t pay any attention to it.

BATTLING OTHER DEMONS

My first encounter with steroids was about two weeks before Mr. World [in 1979]. I remember taking a shot, walking home, collapsing in the door. My lady friend dragged me in the house. I collapsed because of the fact that when you take steroids, there can be blood-pressure issues. And for a person that has sickle cell, like I do, that’s just not good. So I was getting no oxygen to the brain, no oxygen to the heart; I’m almost probably going into a cardiac arrest. She was able to drag me to the bathtub and put cold water on me. Now, you might not believe it, but that saved my life. I went to New York and won Mr. World two weeks later, and I’m thinking, This is madness!

EXPERIENCING INJUSTICE

When I came to Los Angeles in 1975 from Florida, I was denied a professional contract. By the '80s, I’d moved to Europe, and I was based there basically my whole career, almost 13 years. Over there, I was treated completely differently. I was able to work and do exhibitions and seminars. I made enough money to buy a little home in Holland. So I think, something good, something bad—that’s just how life is. It’s not perfect; it didn’t make you any promises. You have to go in there and make life, whatever life you want, all on your own. Nobody’s gonna give it to you. It inspired me, bro. I just kept working.

STAGING A COMEBACK

I came back in 1994 for the Masters Mr. Olympia. I was standing onstage and they announced, “The first Masters Mr. Olympia winner 1994, Robby Robinson.” I remember all the obscenities I was called. I remember hearing all the fans—everybody booed. After the judging, after the show was over, they normally have a big banquet, and that night there was no banquet, there was no party, there was nothing. That hit me hard. And you’re talking the auditorium is packed, thousands of people screaming and yelling, you know, for Lou [Ferrigno]. But when the judge said, “The first Masters Mr. Olympia is Robby Robinson,” everybody let out boos.

BECOMING MORE VOCAL

You can’t break me down mentally; the only person who can break me down is myself. And I just never listened to the negatives. For the Masters Mr. Olympia, I knew that if I could go in there and get myself in great shape, that whatever competitors—whatever racism, discrimination was there—I thought my physique could take it down, and it did. I made it through all of that, and I just felt that you got to say something. [In the early ’80s] I was suspended because of the fact I’d spoken out about “Hey, you know, listen, there’s really no money here; people don’t really care about you. If you don’t care about yourself, you’re not gonna make it.”

STAYING READY FOR WHATEVER

You have your wishes and dreams, like to go to Hollywood and be labeled into that world, like Arnold with Conan and Lou the Hulk. I thought it would be a great thing to do. But naaah, they weren’t ready for that. You know, out there in that world at that point in time, those doors were just not open. Today I’m in the process of doing a documentary on my life. I don’t really have the desire to want to be a movie star now. But if someone came along and said, “Hey, listen, run over there and jump over that wall and fire your machine gun,” I’d give it a try.

CONTINUING TO DO THE WORK

No disrespect to any of the guys who are out there trying to create a great physique, but I don’t see it as art anymore. I just see big bodies out there that are all just a large amount of anabolics and whatever else they can use to get that physique. And you know, I can’t admire it. I’m in a very happy place with what I’ve accomplished. Hard work pays off. I continue to say that.

Interview by Kristian Rhim. Photograph by Erik Carter.

Rosa Parks's Lawyer Fred Gray Has Spent His Life Battling Segregation

CIVIL RIGHTS LAWYER, 89, TUSKEGEE, AL

I’m the youngest of five children. My father died when I was two. My mother had no formal education, except to about the fifth or sixth grade. But she told the five of us that we could be anything we wanted to be if we did three things. One, bring Christ first in your life. Two, stay in school and get a good education. And three, stay out of trouble. I have tried to do all three of those things. And they have helped me to do all the other things I have done.

When I finished my high school work, at that time, as a young Black man in Montgomery, basically the only two real professions you could look forward to, one was preaching and one was to be a teacher. And if you did either one, you did it on a segregated basis, because everything was segregated. So I decided I would be both. And I enrolled at what was then Alabama State College for Negroes, now Alabama State University. It is on the east side of Montgomery, and I lived on the west side of Montgomery. So I had to use the public transportation system every day.

As I used that system, I realized that people in Montgomery, African Americans in Montgomery, had a problem. They had a problem with mistreatment on the buses, and one man had even been killed as a result of an altercation on the bus. I didn’t know nothing about lawyers, but they were telling me that lawyers helped people solve problems. And I thought that Black people in Montgomery had some problems. And not only that, everything was completely segregated. So I made a commitment, a personal commitment, a private commitment. And that was that I was going to go to law school, finish law school, take the bar exam, pass the bar exam, become a lawyer in Alabama, and destroy everything segregated at the time. Now, for a young teenager to think that way, you may say I was thinking a little bit out of the box.

On the seventh of September 1954, I became licensed to practice law in the state of Alabama. I then was ready to begin my law practice and begin destroying everything segregated I could find.

Dr. King came to Montgomery just about the same time I started practicing law. He was installed as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in October of 1954. But nobody knew Martin Luther King. He didn’t come to Montgomery for the purpose of starting a civil rights movement. I doubt whether he knew anything about civil rights. The church that he became pastor of, Dexter Avenue, was a small African American Baptist church that consisted of basically educated persons who were employed by some governmental agency or another, and all of those governmental agencies enforced segregation. So that church would have been the last church whose members would have ever filed a lawsuit to desegregate anything in Montgomery. And the pastor that they had before him, Vernon Johns, they got rid of him because he was too liberal. So nobody knew anything about Dr. King when he came to Montgomery. And, but for what Mrs. Rosa Parks did, and what Claudette Colvin did—if they had not done that, probably nobody would ever have known who Martin Luther King was.

I had met Mrs. Parks when I was in college at Alabama State. She was then and for quite a while secretary of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP. She was also the director of the youth program, and of course the young people she was dealing with when I was in college were just a little bit younger than my age. So I used to visit some of her meetings. After I came back to start practicing law, I renewed my relationship with Mrs. Parks. In our meetings we had talked about the way a person should conduct themselves if the opportunity presented itself and they were asked to get up and give their seat on a bus. And Mrs. Parks was the right type of person. We didn’t want somebody who would be a hothead, or who they could accuse of being disorderly, but someone who would let them know they were not going to move. If they were told that they were under arrest, they would go ahead and be arrested. And we would try to be sure that somebody was there to take care of them.

We also knew that it was going to take a lawsuit in federal court in order to have the laws declared unconstitutional. And we knew that would take time. So we felt we couldn’t tell the people to stay off of the buses until they could go back on a non-segregated basis. But the plan was, let’s tell them to stay off of the bus one day, on Monday, the day of Mrs. Parks’s trial. And then we’ll decide where we go from there.

Somebody had to be the spokesman for the group, to tell the people and tell the press what we were doing and why we were doing it. It needed to be a person who could speak, and someone said to me, “Well, I’ll tell you, Fred, the person who can do that the best of anybody I know is my pastor, and that’s Martin Luther King.” He hadn’t been in town long, and hadn’t been involved in any civil rights activity. But he could move people. I said, “If he can do that, that’s the kind of person that we need.”

It didn’t take long to try Mrs. Parks’s case because I knew they were going to find her guilty, and I was gonna have to appeal it. So I simply raised the constitutional issues. We had a trial that took less than an hour. She was convicted; we posted the appeal. And they had a mass meeting that night at the Holt Street Baptist Church. And when Dr. King spoke, everybody knew. And that is the beginning of how the bus boycott started. And the people stayed off the buses for 382 days.

As a result of people seeing what had happened in Montgomery, the thought then was, If you can solve a problem with staying off the buses, then Black people can solve their problems elsewhere. So you had the students up at A&T that started the sit-in demonstrations at the lunch counter. You had all of these people getting involved in what developed into the civil rights movement as a result of seeing what the 50,000 African Americans had done in Montgomery.

I have now been practicing law for some 66 years, and it all started because when I was a student at Alabama State, I made a decision that I was going to destroy everything segregated I could find. Doing away with segregation on buses was just the beginning of my career. I’ve filed lawsuits that have ended segregation in the University of Alabama. I represented Alabama State in a case that ended up desegregating all of the other institutions of higher learning. Our responsibility, and the responsibility that the NAACP and other groups were working on since slavery, was filing lawsuits one at a time, one area at a time, and getting the court to declare it unconstitutional. We have for the most part knocked out those laws. However, the most discouraging thing for me and my practice in Alabama was that I was naive enough to believe that when the white power structure in this state saw that African Americans could perform as well as they, or better in some instances, that they would be willing to accept it. But while we have knocked the laws out, the attitudes of some persons have not changed. But we have made a tremendous amount of progress.

The best advice I can give to young people—and old ones too, for that matter—is, look in your communities. See the problems that exist? Do as we did in Montgomery: Let’s talk about those problems. Don’t just run out on your own and try to solve it all, but work with others. And you may find that there are other people in the community who believe that what you think is a problem is also a problem to them. And you may be able to get together. And by talking and working and formulating, you just might start a movement.

Use your own good common sense and help to finish the job of destroying racism and destroying inequality. Things certainly have changed, but what has not changed is racism and inequality. And that was my object, to get rid of those two things. But it’s gonna be up to you to do it.

As told to Hali Cameron. Photograph by Andi Rice.

Faye Wattleton, the First Black Planned Parenthood President, on Her Fight for Reproductive Rights

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 77, NEW YORK, NY

The first African American and youngest president of Planned Parenthood, Faye Wattleton spent decades advocating for women’s health and reproductive rights. She was interviewed by Rachel Williams, a political science major and communications minor at Alabama State University, about her experiences and the work that still needs to be done.

Rachel Williams: Did growing up in a strict religious household affect your views around sex and sex education?

Faye Wattleton: The Bible says to be fruitful and multiply, so there was really no sex education within my family, and at school, it focused on menstruation and not sexual development or healthy sexuality. Sex outside of marriage was viewed as sinful and condemned. But all of that did inform how I work to oppose the people who want to overturn reproductive rights—I understand their vernacular and way of thinking.

RW: How was your activism impacted by your education and time as a nurse?

FW: Had I not pursued the medical degrees and career that I did, I might have taken a very different path and probably wouldn’t have been open to a wider point of view and a world beyond what I grew up in.

RW: Religion can be a factor for many people in the reproductive rights discussion. What’s your point of view on that?

FW: What I think is worth highlighting is that my pastor mother’s teaching wasn’t that the government should impose its will. I never once heard her suggest that there should be laws to enforce religious tenets. But religion is still being used to circumscribe women’s behavior. As a nurse and midwife in the '60s, I was exposed to low-income women at a time when they were injured and killed in an effort to control fertility—something to which it seems politicians today want to see us return. There is no question that as we go backward, those who will be most harmed are the people who don’t have the resources to overcome these obstacles, particularly women of color.

RW: As president of Planned Parenthood, you made a lot of strides, but it seems like there is still so much to do. What now?

FW: I think we really need to maintain perspective about how long this area of a woman’s life has been under attack. And it’s really important not to see this as a Planned Parenthood issue. It’s incumbent on every woman to see this as her issue. We’re not without power to change things, but we really have to take responsibility and get engaged to directly hold public officials accountable for stepping away from women’s bodies and leaving us to make the best decisions for our own lives.

RW: Another area of women’s health where we see a lot of disparity is maternal mortality and how it disproportionately affects Black women. Can you speak to that?

FW: We have to take a more holistic approach to maternal mortality. The focus shouldn’t only be on childbearing as a woman’s role; it should look at health inequities across the board and how that foundation affects pregnancy. There is no reason for there to be a gap between those who have good health care and those who do not.

RW: What message do you want to send to women coming behind you who continue to fight for their rights?

FW: Recognize the long, difficult, and dangerous journey so far, and that there’s a great debt to pay. People have died defending and working to protect a woman’s right to control our own fertility. You can march, write to politicians, or give a few dollars, but each of us has the responsibility to take it up in whatever way we can.

Interview by Rachel Williams. Photograph by Tiffany L. Clark.

Horticulturist Flora Wharton Has Lessons for Every Businessperson

HORTICULTURIST, 75, CLEVELAND HEIGHTS, OH

In 1976, Flora Wharton opened floral design business Herb & Plants in Shaker Heights, a predominantly white suburb of Cleveland. "Whether I was getting push back from white people that were uncomfortable with me around or even some Black people that said I was trying to be white having my shop in Shaker Heights, I didn’t buy into it,” says Wharton. "My passion for plants was my purpose. Nothing and no one was going to stop me.” Here’s how she grew her success and self-confidence along with her beloved flowers.

Sara Bey: What first sparked your interest in plants and horticulture?

Flora Wharton: My mother named me Flora after her aunt Flora Bell, who was the first Black head nurse at University Hospital. She always used to tell me “flora means plant life,” so I was predestined to be a plant lover—it’s who I am! But my father Lewis Washington Wharton truly inspired me. He was from Clemmons, North Carolina and back in the day when he grew up, people grew their own food. So, we had a garden in our backyard when I was a girl and I always loved working in it. That was the way my father and I bonded. We grew tomatoes, cabbage, green beans, we would grow it all. My father was very popular in the Glenville area of Cleveland and he would help other Black families by giving them fresh vegetables to eat right. He was the first entrepreneur I ever knew. Everyone else worked for GM or big companies and my father had his own business as a builder and I was proud of that.

SB: Tell me about your shop: Was it difficult as a Black woman to build a business in what was then a wealthy, predominantly white area of Cleveland?

FW: A Black woman opening a plant shop in Shaker Heights was huge news. When I went to elementary school, it was Black and white kids together. When I went to junior high school, it all changed. All my [white] friends went to Cleveland Heights and we went to Glenville. I lived through that racial divide of the city. I never let that hold me back. I believe people are people. My husband was an artist and had a studio in Shaker Square, and told me that there were store spaces so I decided to open Herbs & Plants. Every major newspaper and local magazine came out and took my picture. After the articles came out, an executive from Cleveland Hopkins Airport came to the store and offered me the contract to provide and take care of all of the plants at the airport. So from the beginning, I had great press and that helped get the shop off the ground and nothing was going to stop me. Looking back it might have been more difficult than I allowed myself to realize but I stayed focused on my goal.

SB: Do you have any advice for young women who dream of opening their own business?

FW: First, you have to have courage because it is scary out here, especially for a Black American woman because we’re still disenfranchised in 2021. And people will try to take your joy, which is scary. Get rid of all the joy robbers and keep looking up even when you want to look down.

SB: There’s a movement amongst Black women today to “claim joy.” Is there a time when you had to do that?

FW: My husband used money to control me and one day I had a serious “a-ha” moment—I realized I had my own money! I was so used to being controlled, it didn’t occur to me that my business had become a success. I decided not to do what he told me and it became scary. He came into the plant store one day and said, “Come on, it’s time to go,” in a very controlling way and I knew I had to go on without him. As soon as I was able, I filed for divorce. I loved his talent but I loved me more.

SB: You were ahead of your time in your support for the LGBTQ+ community. Why was it important to you to be an advocate?

FW: I’m the type of person that thinks whatever you are and whoever you are, that’s wonderful. I don’t believe in people judging people. When you're born God makes you who he wants you to be. People will judge you for what you are, what you do, who you love—that is none of your business. You've got to live your own truth. I don't care what human beings think about me because I know what God loves.

SB: What’s next for you?

FW: I feel this opportunity to talk about my life has given me a new lease on life. I was starting to feel that when you get old, you become invisible. I didn’t think anyone could see me anymore. This experience has made me think anything is possible. I’d love to help people find the joy that comes from having a beautiful garden. I always want to be surrounded by beautiful flowers and plants.

Interview by Sara Bey. Photograph by Cydni Elledge.

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, which records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021.

Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like