Black families using DNA, genealogy to fill in historical gaps left by slavery

Laurie Scott-Reyes drove for two hours, alone, on a back road from Crawford, Alabama to Sparta, Georgia, retracing in reverse the migration her ancestors made after slavery ended.

Anxious to reach her destination and determined to make the journey, she took in the sights around her, staring at dilapidated homes, rusted over storefronts and rows and rows of pine trees. Years ago, her family had fled Georgia looking for a better life and made Alabama their new home. Now, she felt a pull to come back and see what they had left behind.

“It was like driving into the past,” Scott-Reyes said, thinking of her forebears. “Their spirits are very real to me, and for me, that was like, a great achievement, and I felt like I was doing it for my tribe.”

Her accomplishment: Tracking down the William Hurt Plantation, where her family had once been enslaved.

At the plantation, Scott-Reyes joined a growing wave of Black Americans who in recent years have been exploring their genealogy at historical sites. They have been digging into increasingly available information about their families’ existences in the United States — history dating back more than 400 years ago, when kidnapped Africans were first brought to Virginia and sold into slavery. These efforts have led to new explorations of former slavery sites, to deep dives into historical data, as well as to reckonings in personal homes over family trees and in the nation’s institutions which have had to face controversial truths about the role slavery played in American society.

For Scott-Reyes, who lives in Florida, her journey into her family’s experience with slavery brought her more than 500 miles southwest of Jamestown, Virginia to the Hurt plantation in Georgia. Scott-Reyes toured the plantation where William Hurt once controlled some 2,000 acres of land. She said it was sad to walk around the muscadine and scuppernong grape vines to view the sleeping quarters and the cookhouse for the enslaved.

“It was almost like I was driven by something that was bigger than myself,” said Scott-Reyes who has since written a book titled "Against the Tempest." “It's no longer just me, my curiosity and wanting to know my people. I wanted all the descendants to know who these ancestors were so it became more for them than for me at a certain point.”

Historians, genealogists and personal researchers like Scott-Reyes have long sought answers from plantation sites.

One of the most famous events focused on that goal that took place in 1986 when descendants of enslaved Black Americans gathered for a reunion in Somerset Place near Creswell, North Carolina, at a plantation that was once home to multiple generations of enslaved people. Dorothy Spruill Redford, author, historian and former executive director of Somerset Place, helped organize the event.

Researchers have also found like minded individuals through The Slave Dwelling Project, a group that raises awareness with overnight stays in historic buildings and other programs.

Joseph McGill Jr., the project’s founder who is based in South Carolina, was inspired to start the organization in 2010 after staying overnight in a restored South Carolina slave cabin. A year later, he slept near an auction block in Brenham, Texas. He has now visited slave dwellings in 25 states in the past 10 years. He says it's critical that descendants of African slaves tell the stories of what happened at sites like Somerset Place.

“If we're not in the audience or participants in what these places offer, they're going to continue to sugarcoat the story, to tell the ‘Gone With the Wind’ version of history,” McGill said. “The Slave Dwelling Project counters that."

Alex Haley’s 1976 novel “Roots: The Saga of an American Family” and the landmark 1977 miniseries based on it inspired many African Americans to explore their family histories. In 2019, the 400th anniversary of the landing of the first documented Africans in English North America, at Point Comfort in what is now Virginia, provided another boost to genealogy engagement.

Ric Murphy, former vice president of Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society and author of the book “Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia,” urged Black families to consider researching their genealogy. He's written a book, "Arrival of the First Africans in Virginia." "American history is our history, and our history is American history,” he said.

Black researchers have been flocking to family records and submitting their DNA to genetic services for answers. Others have been using oral histories to map out their family history like Bettye Kearse, author of "The Other Madisons: The Lost History of A President's Black Family," who has evidence that she is related to former United States President James Madison.

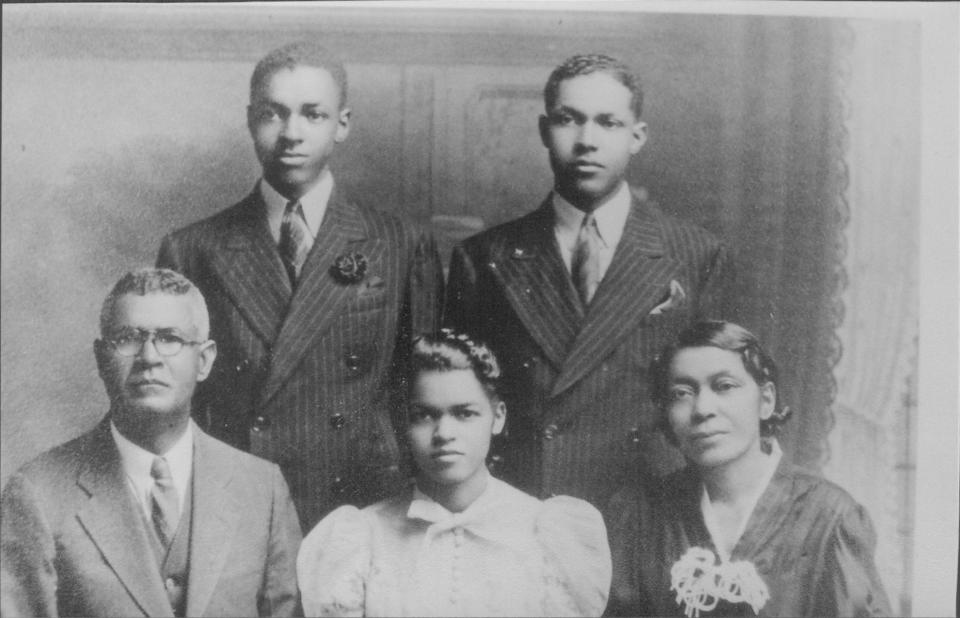

“Always remember, you're a Madison, you come from African slaves and a president,” Kearse said quoting a family credo that she began hearing at age five. Years later, she became the family griot — a West African term for the person responsible for maintaining the oral histories of a family — and the keeper of scrapbook photos and other artifacts.

“I'm very big on scrapbooks, boxes and tangible things that people save in basements and attics and closets and all sorts of places,” Kearse said. “It’s very important to do it, save it and pass it on.”

Museums and institutions have also been engaging more with descendants of the enslaved in the last several years. Some have reformatted their programming and others have used tools to help catalog the lives of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

In December, Michigan State University launched a searchable database, Enslaved.org, that includes short biographical sketches. The University of Maryland and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation are partners in the project.

Stephen Hammond, a family historian and expert on the lives of enslaved people at the Arlington House museum in Virginia, said more information-sharing allows researchers to be able to better explore genealogical cases. In the past 20 years, Hammond said staff at historic places such as George Washington's Mount Vernon estate, Madison's Montpelier and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello have started to share more about the history of enslavement.

Hammond is a seventh-generation member of the Syphax family, which is connected to Martha Washington, the wife of the first president. He currently has a DNA study underway that could confirm not only the family's African ancestry, but also how it intersects with white Washington descendants.

Subscribe: Help support quality journalism like this.

“It's exhilarating for me to think that we can use the knowledge of our forebears to make a difference in our future,” Hammond said. “And I would hope that we can inspire other people to think about that in that way, as well.”

Historical research can be difficult for Black families because many were torn apart through the slave trade, documents have been burned, names have been changed, and at times, even living family members have dismissed DNA requests.

Cheryl Brown, who is based in Virginia, experienced some of those challenges after uncovering a marital affair through DNA tracing and going most of her life without knowing her father or her family because she was adopted. But after responding to a persistent emailer claiming to be her cousin, obtaining her birth records and taking an Ancestry.com DNA test, she met her father two years ago.

Lonnie Lee Jr., Brown’s 81-year-old father, said he was elated about his daughter’s efforts and glad to meet her for the first time at a tearful family reunion in Charlotte, North Carolina. “I knew she existed somewhere and I was just glad that she found me,” he said.

Brown has also learned about a late sister, connected two family members to their birth fathers, and gained over a hundred new family members. She is now researching slave transaction records and motivated to dig even deeper.

“I'm pressing forward,” she said. “I'll never tire from the research. There's just so much to do.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black families use DNA, oral histories to fill in gaps left by slavery