Black genealogists' surprising findings using Ancestry's digitized U.S. Freedmen's records

Regina Vaughn has been painstakingly tracing her family legacy dating back to slavery to keep a vow she made to her late mother more than a decade ago.

She has spent countless hours, days, nights, weekends, sometimes holidays through weary and watery eyes from all of the tears while trying to uncover her lineage, primarily through written documents and files on microfilm.

The retired Philadelphia public schools teacher has lost count of how many miles she has flown – to places as far as Cameroon, West Africa, or driven up and down the tobacco roads to states like Virginia and South Carolina to learn more about her ancestors.

Many times, however, Vaughn kept hitting a roadblock that many Black Americans face finding their roots. The infamous "1870 Brick Wall." That's when tracking information back to when Congress passed the Freedmen's Bureau in 1865, an act that created a federal agency designed to help millions of formerly enslaved Black Americans in the South adjust to freedom after the Civil War.

But now, Vaughn said a new free search created by the online DNA site Ancestry.com has been helping her learn more details about her family during the Reconstruction more quickly and why the name "Tribble" means so much to them.

In August, Ancestry released what it says is the most extensive and searchable Freedmen's Bureau records by making available more than 3.5 million documents from the National Archives and Records Administration. Some records date back to 1846.

And more than a month since the release, researchers like Vaughn are discovering things on Ancestry they say would've taken them years, or things they would have never found. The site includes details such as labor contracts, bank records, marriage licenses, schools, and food and clothing for emancipated Black Americans.

"This has opened up a whole new world for my family and me," Vaughn said. "It's been vital."

Ancestry's initiative is a "game-changer" for researchers and families wanting more knowledge about their heritage – for better or worse, said genealogist Nicka Sewell-Smith.

"It's both sobering and celebratory because Black people have a hunger to connect back with that time and seek to add breadth to their family history," said Sewell-Smith, an Ancestry consultant. "DNA can take us back to a continent, but we still have a desire to know about our ancestors stateside and make that deep connection about our family and finding our unique American history."

►Fight the power: Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

►Seven days: 1961, the year young activists helped change the course of American history

Even though original Freedmen Bureau records have been available for years and digitized by the National Archives and other genealogy sites, including Family Search and MyHeritage.com, researchers often say it can be cumbersome with the maze-like searching.

'Not just Black and White'

Longtime genealogist Yokota Strong agrees. He was able to identify an essential piece of his family history he has been scouring for decades within an hour after the Ancestry digitized Freedman's release in August. This included finding eight "great" relatives, including five great-grandfathers and three great-grandmothers.

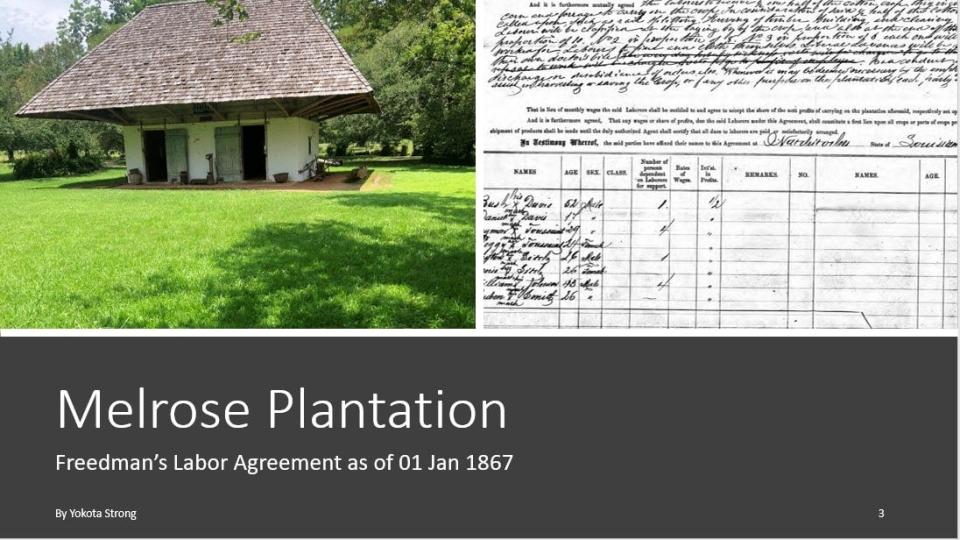

But Strong was eager to know why one of his great-grandfather, born in Virginia, had but hard to find family ties in Louisiana. It turns out that his second and third great-grandfathers, Daniel Davis and Bush Davis, respectively, were sharecroppers on a renowned Black creole family-owned plantation for free Blacks called the Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches Parish. The plantation is a national landmark.

Strong said many of his family members gasped and were silent with the revelations.

"It was a pretty startling discovery," he said. "It feels strange to know that my own family was part of that narrative of a noted Creole-owned plantation, It doesn't make it better or worse, but we're so used to seeing, hearing, and learning a different narrative around enslavement and sharecropping.

"It's such a relief to be able to add more context to my ancestors and see them as human beings instead of just names."

Strong said Ancestry helped his family trace their great-grandfathers' history to 1867, three years before 1870, when the U.S. Census recorded and counted the full names of those who had been enslaved.

"The whole system of slavery was complex and not so much just black and white," Strong said. "Colorism also plays into the history, and this is an example of that."

For Strong, the revelation of his great-grandfathers' history provides more nuanced branches to his family tree.

"Even for the free people of color, it does make you a bit upset as you truly grasp the reality of their situation," Strong said. "I'm appreciative that we can give them some sort of closure as it makes it even more authentic about who they are, that they worked hard and sacrificed so much.

"It just reminds me of how American we really are," Strong added, with an emphasis on the word "we."

The fascination can lead to both exhaustive and exhilarating searches, Sewell-Smith said. She often spends Friday evenings researching with other genealogists to "see if we can find something incredible."

Their excursions can last well past midnight.

"We call it Freedmen's Bureau Fridays," Sewell-Smith said. She recalled one gathering when the researchers looked to see how many Black Americans listed in the Freedmen's Bureau were voters. (While Congress passed the 15th Amendment in 1870 that granted Black men the right to vote, whether they could vote was another matter.)

"When you peer into some of the things happening as the country was trying to restabilize itself back then, there are a lot of parallels that we currently see and can relate to today, especially around voting rights," Sewell-Smith said.

Sewell-Smith said she's still surprised many are unaware of the Freedmen's Bureau and its place in U.S. history.

"A lot of people don't know it existed, and once they about learned it, they learn that it can provide so much context about their ancestors beyond an obit and maybe a headstone," Sewell-Smith said.

'Somebody has to do it'

That's what Vaughn said her mother wanted her to pursue with tracing her family legacy. In 2010, Vaughn assumed the role of family historian at the insistence of her mother, Othella Ross Vaughn, who died in 2017.

Vaughn said her mother was inspired to learn more about their lineage after watching the groundbreaking Emmy-winning TV miniseries "Roots," based on author Alex Haley's 1976 novel about a man kidnapped from Africa and sold into slavery in America and his descendants.

Vaughn's mother traveled across the country to find documents and listen to oral tales from family elders. She even wrote and self-published a family history book titled "Sankofa: The Saga of the Tribble Family (1826-1986)" in 1986.

Vaughn said her mother believed in one of the Ghanian word's meanings, "You must know the past to move forward in the future." The book traces the first four generations of her family surnames, Ross and Tribble, the latter of which has direct ties to enslaved family members.

Vaughn, an only child, felt she owed her mother, who was a lifetime member of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and once gave a lecture at one of its conventions titled, "A Layman Looks at Genealogy."

Vaughn's mother first enrolled at Temple University in 1947. She would reenroll at Temple over the next five decades while raising a family before finally earning her sociology degree in 1993 at age 69, three days before her granddaughter graduated from the University of Virginia.

Could Vaughn let her mother down? No.

"My mother told me very bluntly, 'Somebody has to do it,'" she said. "I couldn't ignore her wishes any longer."

So as Vaughn was able to pick up where her mother left off, there was one ancestor her mother could track down but had no substantive background on him.

His name was Hampton Tribble, Vaughn's maternal great-great-grandfather, a freed slave.

"The paper trail went dead," said Vaughn, blaming that dreaded "1870 Brick Wall."

"We were never named in the census," Vaughn said. "We couldn't find anything. For years!"

But about a month into looking for her relatives using Ancestry's new digitizing of Freedmen's Bureau records, Vaughn found a labor contract with Hampton Tribble's name dating back to 1866, along with his owner's name, Elijah Tribble.

Vaughn said that Elijah described Hampton as "honest, obedient, faithful, and prompt" in the labor contract.

Vaughn was also able to find a photo of Hampton Tribble and found he was born in October 1848 in Newberry County, South Carolina, and died in November 1928 in nearby Saluda County.

"I cried. It was very emotional for me," Vaughn said. "This big gap is finally filled."

Vaughn, who belongs to three genealogical groups in the Philadelphia area, continues to trace the lineages of five other surnames related to her.

"And I'm working on finding if Hampton (Tribble) possibly had a brother," Vaughn said. "I'm not giving up."

Vaugh said she's sometimes at a loss for words about what her ancestors experienced.

"What they did, I don't know if sacrifice is even the right word to describe it," said Vaughn, choking up. "I appreciate that they survived and endured so that I can thrive and tell their stories."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black Americans' Family trees: This geneaology tool builds connections