A Black history lesson on soul food is feeding elementary students’ minds through their bellies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

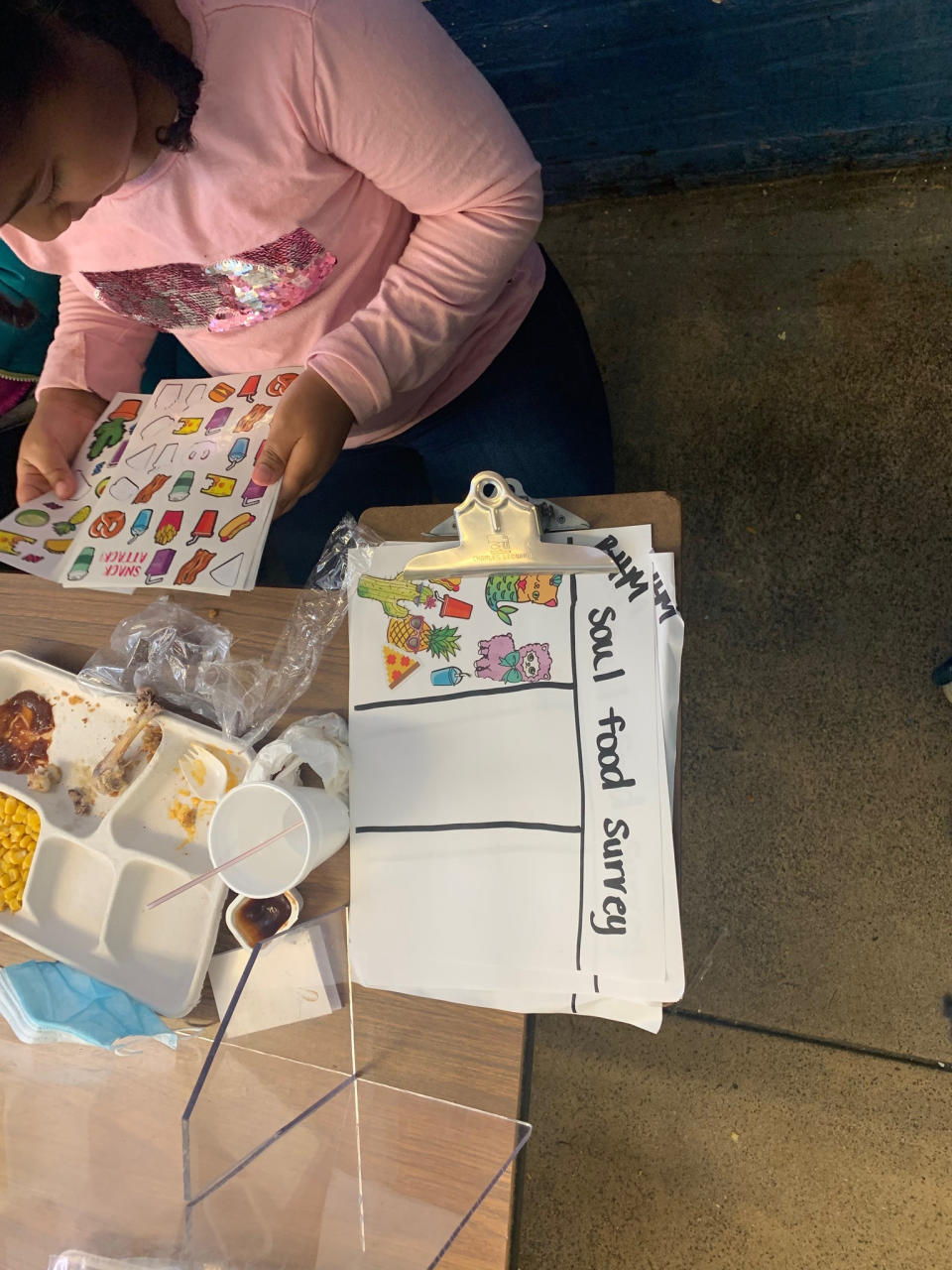

This month, as elementary students take bites of baked macaroni and cheese, they’ll be learning about its distinctly American history — and the enslaved Black chef that made it possible.

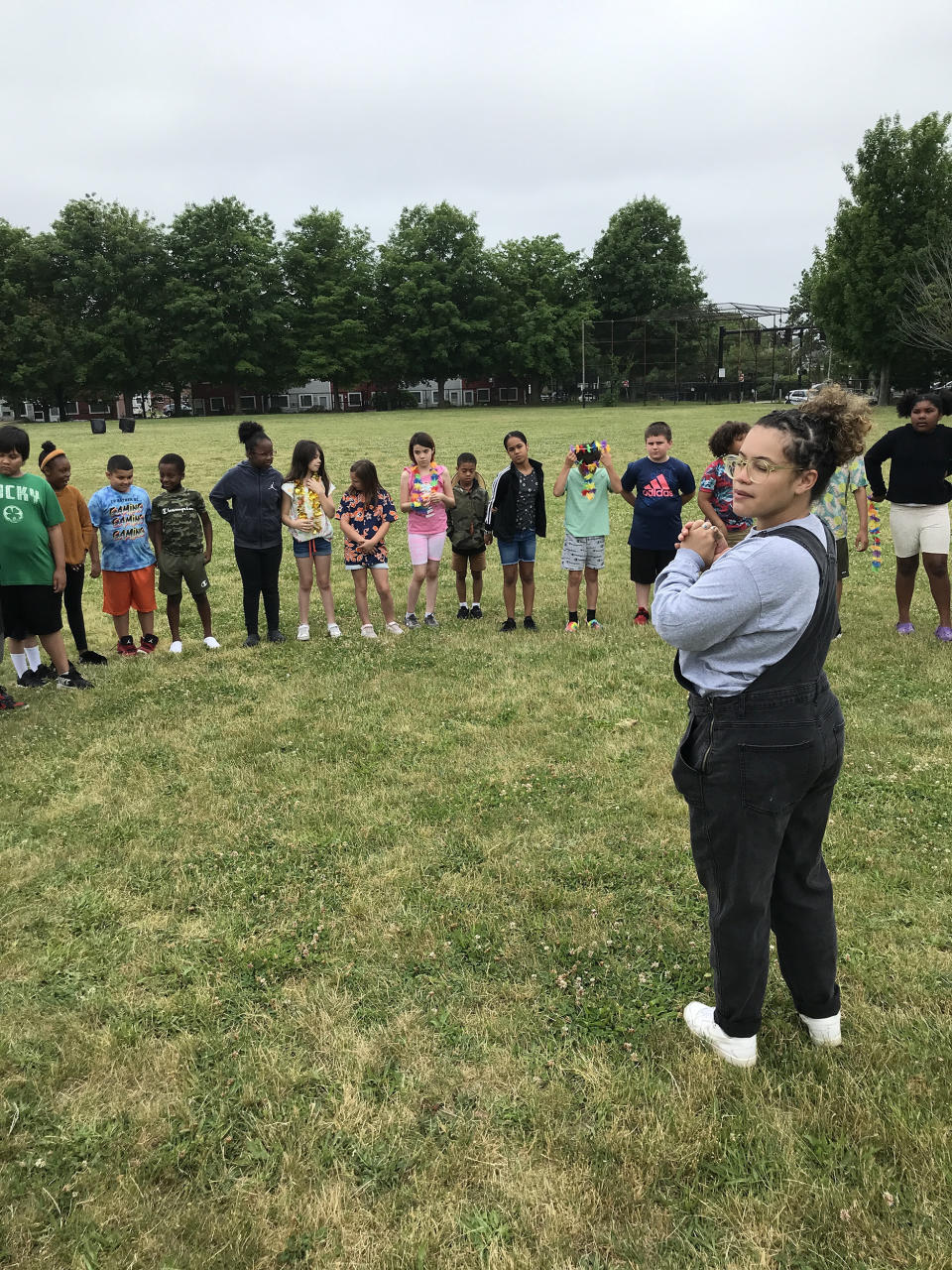

“It used to be called macaroni pie. It was created by a renowned chef, an enslaved chef,” Shalynn Brooks, a FoodCorps service member and Fall River, Massachusetts native tells TODAY.com.

She’s referring to James Hemings, the chef enslaved by Thomas Jefferson and the mastermind behind many of America’s favorite dishes, including — but not limited to — mac and cheese. “He wasn’t recognized for it, it was recognized as Thomas Jefferson’s,” she says.

For Black History Month, Brooks has created a special lesson that teaches elementary school students the connections between Black people and some of the most iconic American foods. It was first reported on by the Standard-Times.

Now in its second year, the program delivers the lesson to 19 elementary schools in the New Bedford Public School system in Massachusetts to give students a look into how some of their favorite foods came to their lunch tables.

“This year I chose candied yams, cornbread, a fried turkey leg with a side of barbecue (sauce) and baked mac and cheese,” Brooks says, adding that this year, students also get to taste test a cafeteria-friendly version of collard greens.

“The way the cafeteria is set up, it’s not like we could do it how we make collard greens at home,” Brooks says, referencing the often-hours-long process involved in making the soul-food staple. “But we did an adaptation, and they get to try that next week on top of being able to have the whole meal. They’ll have a deeper understanding of it.”

After she graduated college in 2021, Brooks became part of FoodCorps, an organization that works alongside educators and school nutrition leaders to provide kids with meals, food education and culturally affirming experiences.

FoodCorps is working in partnership with the New Bedford Public Schools and Grow Education, the farm-to-school program of the Marion Institute. Grow supports educators, parents and students through healthy food education, and as part of it, Brooks is educating little minds through their bellies.

“The connection between food and Black history just wasn’t taught when I was growing up in schools,” Brooks says. “What we normally learn about in school is still important, but I just always felt like there was something missing.”

The lesson starts with a history of Frederick Douglass, who escaped enslavement in Maryland in 1838, first arriving in New York and later settling in Massachusetts with his wife. “Frederick Douglass actually lived here in New Bedford,” Brooks says.

The lesson then moves into other icons of Black history — which includes inventors as well little-known changemakers in the farming industry.

In addition to Garrett Morgan, who invented and first patented the idea for the three-position traffic signal, the lesson covers figures like Fannie Lou Hamer, a Black civil rights activist who started the Freedom Farm Cooperative, an organization that sought to make African American farmers self-sufficient in order to alleviate poverty and economic disparities between races.

The lesson also covers lesser-known figures like Henry Blair, who was the second Black man in American history to hold a patent for his 1834 corn planter, which sped up a daunting task in the farming industry at the time.

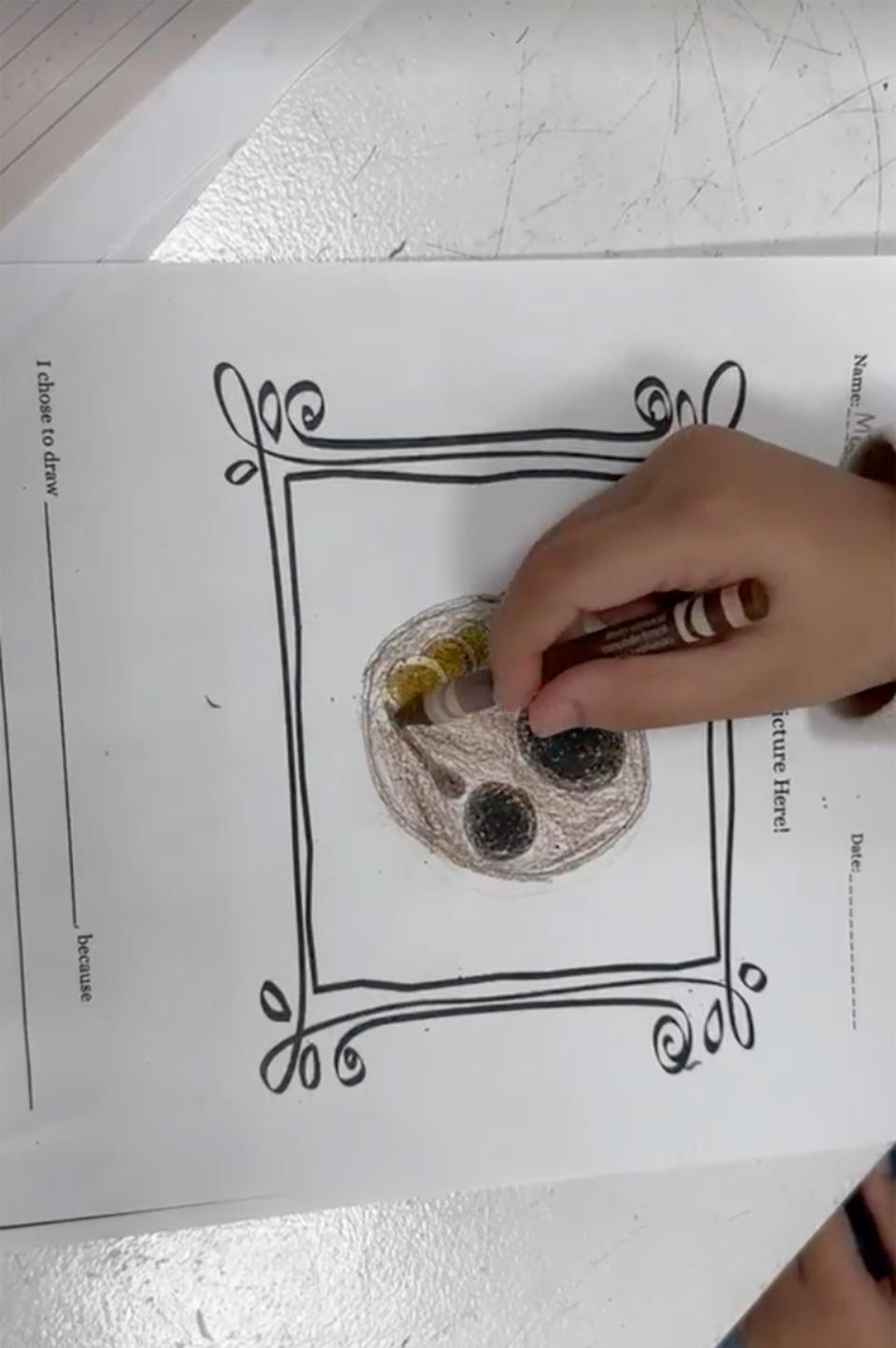

After the lesson, Brooks says students get to pick one thing they learned or that they were really interested in and draw it, which she says really connects the dots for them. “Then they write the reason why they picked that thing or person and then they get the meal,” she says.

Brooks says that growing up, she came to want a deeper understanding of the foods that connect her to her ancestors. That kind of education just didn’t exist in her elementary school experience.

“It was all very much geared towards the trials and tribulations of the Black community and all these things that we had accomplished through that,” Brooks says of the way Black history has been taught in schools, which many educators and parents have said has shortcomings. “I feel like there was a missing part: the celebration and appreciation and a deep understanding of all of it. Through food, that’s the way that I thought would make a good connection.”

Brooks says that being biracial and growing up closer to the Black side of her family influenced her connection to African American cuisine. “Every moment that we shared, there was food between us,” she says.

As for how the kids feel about the lesson, Brooks says they are happy to get a scoop of history along with their lunch.

"Last year, they were ecstatic about it and were asking for seconds," she says, adding that some of the items, like yams and cornbread, have been added to the cafeterias rotation on a permanent basis after so much positive feedback.

For Brooks, seeing the students enjoy the foods she holds most dear has been encouraging as she reflects on her own past.

“When I was younger, I was kind of disconnected. I was fostered, and when I was fostered, I got disconnected with family and the culture and everything,” Brooks says.

“When I got older, I used to go over to my brother’s, and during celebrations he would make collard greens, baked mac, barbecued ribs and things like that, and it reminded me how I really was disconnected for a little while,” Brooks says. “It was really important to me to work on this project, to feed my younger self."

This article was originally published on TODAY.com