Black History Month in Bloomington: what to know, where to go and who to follow

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's note: In honor of Black History Month, The Herald-Times is publishing Black stories, both current and historical, throughout the month of February. A new installment will be published each weekday. As the stories are published, we will collect them here.

Stories to follow

Between breaking down barriers and persisting amidst adversity, here are just a few accounts of local Black stories, spanning from former yesteryears all the way up to present day.

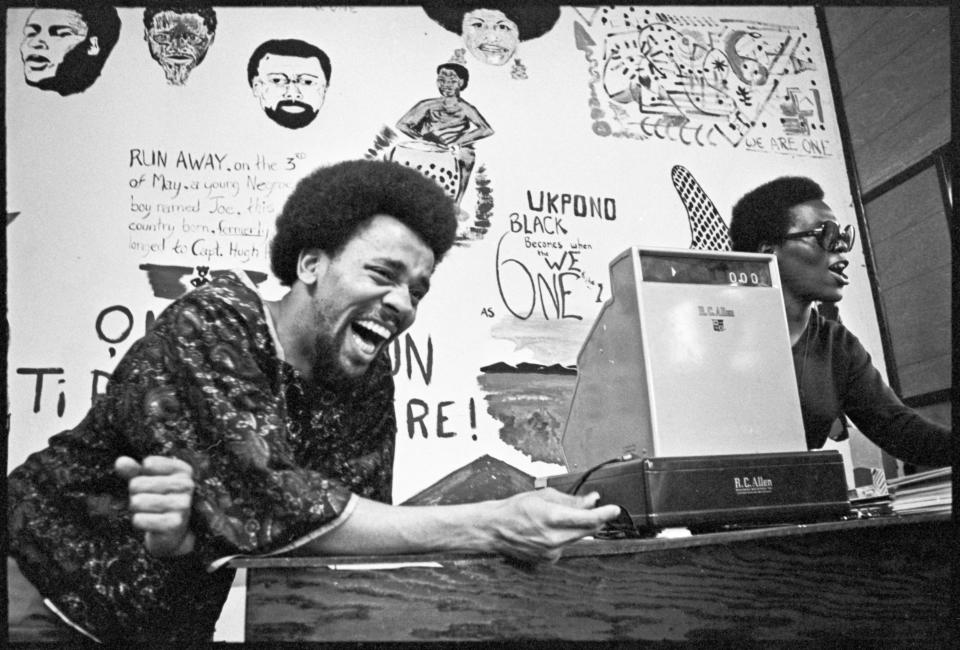

Bloomington marketplace racially targeted in 1968 firebombing

With the help and financial backing of some community members, an IU student founded the Black Market in late 1968 at the the northeast corner of Dunn Street and Kirkwood Avenue. Serving as a social center and cultural marketplace, the Black Market offered books, clothing, records, artwork and other crafts made in Africa or by African Americans. But just three months after its opening, the shop would be bombed with a lit Molotov cocktail.

Read the story:What remains of the Black Market after the 1968 firebombing

Housing discrimination still can be found in Monroe County property deeds

In hundreds of property deeds in Monroe County, hidden alongside talk of utility easements and front yard lines, there's another clause, which past and future property owners were tasked with abiding by: "It is agreed between the above parties that none of above tract of land is to be ever sold to Colored People."

That particular covenant is from a property deed from 1912. It's the earliest record of this sort of racially restrictive language in the county, but it's far from the only one.

Read the full story here:Racist housing clauses are still on the books in Bloomington. How to check your own deed

Indiana University Little 500 race was delayed in 1968 over discriminatory fraternities

In 1968, Indiana University fraternities could still reject membership applicants based on race until some students stood up against the practice — by sitting down.

How a protest changed campus life:In 1968, Indiana University students staged a sit-in at the Little 500 race. Here's why.

Indiana University, Adidas partner for Black History Month jersey line

Briefly swapping out their usual cream and crimson wears, the Indiana Hoosiers basketball team have been donning a different home uniform at Assembly Hall throughout this month. Designed by the Adidas team with input from IU Athletics, the home jerseys utilize state iconography as well as color symbolism to celebrate Black culture through a local lens.

See the re-design here:Noticed Indiana University's basketball team jerseys looking different? Here's why.

How Bloomington reacted to Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, legacy in 1968

On April 3, 1968, civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while standing on a balcony outside his second-floor hotel room in Memphis, Tennessee. As the news of King's death spread, the country was gripped with intense mourning over the passing of the revered minister, who had dedicated his life to racial equality in the United States.

In the weeks following King's assassination, letters from Bloomington residents poured into The Herald-Times, revealing how divisive this time was not only in the country, but in this community. The H-T has re-printed three letters from 1968 to paint a clear picture of this division.

Read the letters here:Op-eds from 1968: Bloomington residents divided by Martin Luther King Jr.'s death, legacy

The Ku Klux Klan repeatedly tried to encroach on Bloomington, Indiana University throughout 1960s

Indiana has a long, deep-seated history with the Ku Klux Klan, but the hate group was never able to grab a stronghold in Bloomington, thanks to ever-vigilant students and local politicians. However, the terrorist organization was able to make its presence locally known in more subversive ways.

Bloomington's brush with the KKK:The Ku Klux Klan repeatedly tried to infiltrate Bloomington. Why it never worked.

Kappa Alpha Psi's birth, history at Indiana University Bloomington

The only surviving fraternity founded at Indiana University, Kappa Alpha Psi, couldn't actually be formed on IU's grounds. Instead, because of social restrictions for African Americans, fraternity members trace its birthplace to 425 E. Kirkwood Ave — at the time in 1911, it was a boarding house for Black IU students. Several of the Greek organization's founding members lived there, forging a loose community that would be strengthened by a formal organization.

Read its history:One of oldest Black fraternities, Kappa Alpha Psi, began at Indiana University Bloomington

People to know

Learn more about some influential individuals who have inspired change, spearheaded innovation or given back to the community.

George Taliaferro's lasting legacy in Bloomington

George Taliaferro had a big hand in the Hoosier football team's trailblazing journey to a Big Ten championship, which still serves as the program’s only undefeated season to this day. Taliaferro would later make history as the first African American player selected in the NFL Draft. But even before then, he had already made a mark in Bloomington for both his on- and off-field victories.

Read the story:How an Indiana University athlete broke the segregation barrier at The Gables in 1947

Bloomington teacher made history as first Black attorney in Indiana

A dedicated educator and Freemason, William F. Teister had many passions and pastimes, but it was his legal achievement that cemented his part in state history — with Bloomington sharing an impressive footnote. It was right here in Monroe County that Teister became the first African American man to be admitted to the bar in Indiana.

More about Teister's life:Bloomington teacher made history as first Black attorney in Indiana

A roaring '20s fundraising venture had Bloomington in an uproar

Mattie Jacobs Fuller was a beautician by trade and had a shop on Kirkwood Avenue, but performing was always in her heart. She became known for toting her portable organ around Bloomington, accepting donations to pay for a building for Bethel AME Church.

Read the story:The story of Mattie Jacobs Fuller, her portable piano and a ‘silver loving cup’

How Bill Garrett's name lives on at Indiana University

As a teenager, Bill Garrett led Shelbyville High School to the Indiana boys’ basketball state championship in 1947; he was later named “Indiana Mr. Basketball” for being the best player in the state during that season.

Though there was an unwritten rule within Big Ten basketball that barred African American players, local Black leaders rallied around Garrett's success, urging then-IU president Herman B Wells and Hoosier basketball coach Branch McCracken to offer Garrett an athletic scholarship. Garrett was IU's first African American basketball player, outperforming his contemporaries on the court. By the time that he graduated, he was a first-team All American and IU’s all-time scoring leader.

How IU honors Garrett's legacy:Behind the name: Who is Indiana University's Garrett Fieldhouse named after?

Black innovators from Indiana University Bloomington

In line with the theme of innovation for 2023's Black History Month, the Herald-Times took a look at a few pioneers who made major strides in their respective fields. Whether they stayed briefly as a fresh-faced Indiana University student, raised a family here as a persevering matriarch, or taught a fleet of young minds as a world-renowned musical prodigy, each of these trailblazers has a piece of Bloomington in their history.

Learn their names, stories here:Black innovation: Three local names who changed the game on state, national scales

Black Revolutionary War vet was in unmarked Bloomington grave for a century

Andrew Ferguson was still a teenager when he participated in a number of pivotal battles, including Kings Mountain, Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. He re-enlisted several times, serving a total of five years and six months. But after his military service, he faced some discrimination while settling in southern Indiana.

More:Revolutionary War vet helped settle Monroe County. Why he remained in obscurity for a century

Progressive politician spearheaded labor, gay rights during 1970s Bloomington

While you may recognize her last name, Tobiatha Eagleson deserves her own chapter in Bloomington's Black history tome. Throughout the mid-1900s, Eagleson was an early African American civic leader who wasn't afraid to go against the grain in order to stand up for those without a voice, including spearheading unionization efforts and promoting equal rights for those in the LGBTQ community.

How she did it:Progressive politician spearheaded labor, gay rights during turbulent 1970s Bloomington

Two decades since Bloomington lost its civil rights leader Ernest Butler

In addition to his 43 years at the helm of Second Baptist Church, Rev. Ernest Butler is credited as the original spearhead behind the Bloomington Human Rights and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. commissions. Throughout his decades of civil service, he was involved in countless committees and boards, primarily those targeting areas of social justice such as fair housing.

More:Two decades since Bloomington lost its civil rights leader Ernest Butler

Places to go

As any architect will tell you, a building is only as strong as its foundation. While time may have weathered and transformed some brick and mortars, these cornerstones remain in the zeitgeist of local Black history.

During segregation, where did Black Indiana University students live?

For several decades in the 20th century, Black students were not allowed to live on college campuses. Indiana University was no exception.

While IU began admitting Black students around the 1880s, the dorm system remained closed to them until 1947. Many other apartment complexes also refused Black residents, so students were forced to live several miles away from their peers. To mitigate that isolation, some local property owners began operating boarding houses. These Bloomington boarding houses were the focus of African American student life for the better part of 30 years.

Find the places here:During segregation, where did Black IU students live? A tour of Bloomington boarding houses

What's in a street name?

Some Monroe County streets names are odd and others bear the name of influential people from the community's past. Learn a little bit about Samuel Dargan Way, Eagleson Avenue, David Baker Extension.

Behind the street signs:What Bloomington streets are named after local Black leaders?

Is former Elks lodge still an endangered Indiana landmark?

Just under two years ago, this cornerstone of Bloomington Black history was flagged by Hoosier preservationists as one of the most endangered landmarks in the state. Statewide advocacy groups were concerned about the lodge's future, if it were to fall into deeper disrepair or even potentially be demolished, the loss would erase a big piece of city history.

Get the answer here:Is Bloomington's B.G. Pollard Lodge still an endangered landmark?

What are the oldest churches in Bloomington, Indiana?

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church and Second Baptist Church, two predominantly Black congregations in Bloomington, are among those that have stood the test of time. Their houses of worship have weathered well beyond 100 years ― with each church's actual origins predating their current physical structures.

Read their histories:What are the oldest churches in Bloomington, Indiana? Long history of community, refuge

Bloomington community center the site of former segregated school

While the Banneker Community Center is now known as a place for pick-up basketball and youth-led recreation, the site's over 100-year legacy on Seventh Street has some complicated affiliations to Bloomington's racial inequality. When Banneker first opened in December 1915, it had three teachers and 93 students. At its peak, the school served 111 students from first through eighth grades.

More:Bloomington's Banneker Center: A retrospective on the site's complex history

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Black History in Bloomington: 20 stories to know