Black History Month: Nine icons who redefined Palm Beach County Black history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In celebration of Black History Month, The Palm Beach Post highlights the contributions of nine historical figures who have left an enduring impact on our history.

These individuals, spanning diverse fields over vast periods, have broken barriers, championed justice, and shaped the course of Black history. From trailblazers in civil rights to cultural icons and leaders in various domains, their stories resonate with resilience, courage, and the pursuit of equality.

Join us as we pay homage to these extraordinary figures, recognizing their pivotal roles in shaping the narrative of Black excellence and fostering a more inclusive world.

Fannie James (1845-1915)

Believed to have had roots in Georgia as a former slave, she and her husband Samuel, both of mixed race, played a pivotal role in the development of what is now Lake Worth Beach.

Settling initially in Tallahassee and later in Cocoa, the couple established the Jewell Post Office in 1889, where Fannie served as the postmaster until 1903. Recognized for her hospitality, Fannie expanded her influence by taking over Samuel's real estate business and emerging as one of the region's leading pineapple producers.

Despite facing racial restrictions, she employed workers from various backgrounds and achieved affluence.

Unfortunately, after selling her home, Fannie was forced to relocate outside the limits of the Town of Lake Worth, which prohibited Black residents until 1926.

Post-desegregation, the city honored Fannie and Samuel with a monument, recognizing them as its first settlers, and highlighting their enduring legacy in Lake Worth's history.

Mildred "Millie" Gildersleeve (1860-1950)

She made history as one of the earliest Black residents of Lake Worth and was Palm Beach County's pioneering midwife.

In 1876, she arrived from Georgia with the Dimick family, and in 1889, she married M. Jacob "Jake" Gildersleeve at the Dimicks' Palm Beach residence.

Embarking on her midwifery career around 1886, Millie worked alongside Dr. Richard Potter, responding to calls from her dock. Their collaborative efforts extended to aiding both settlers and Seminoles.

Acquiring land in Oak Lawn (now Riviera Beach) from the Dimicks, the Gildersleeves established their home and owned property near the Oak Lawn Hotel, where Jake cultivated produce.

By 1916, they relocated to the Pleasant City neighborhood in West Palm Beach, later becoming founding members and officers of the Evergreen Cemetery Association.

Millie's legacy endures through descendants such as former State Representative James Harper and her great-great-great-grandson Bradley Harper, who notably became the first Black judge elected in Palm Beach County.

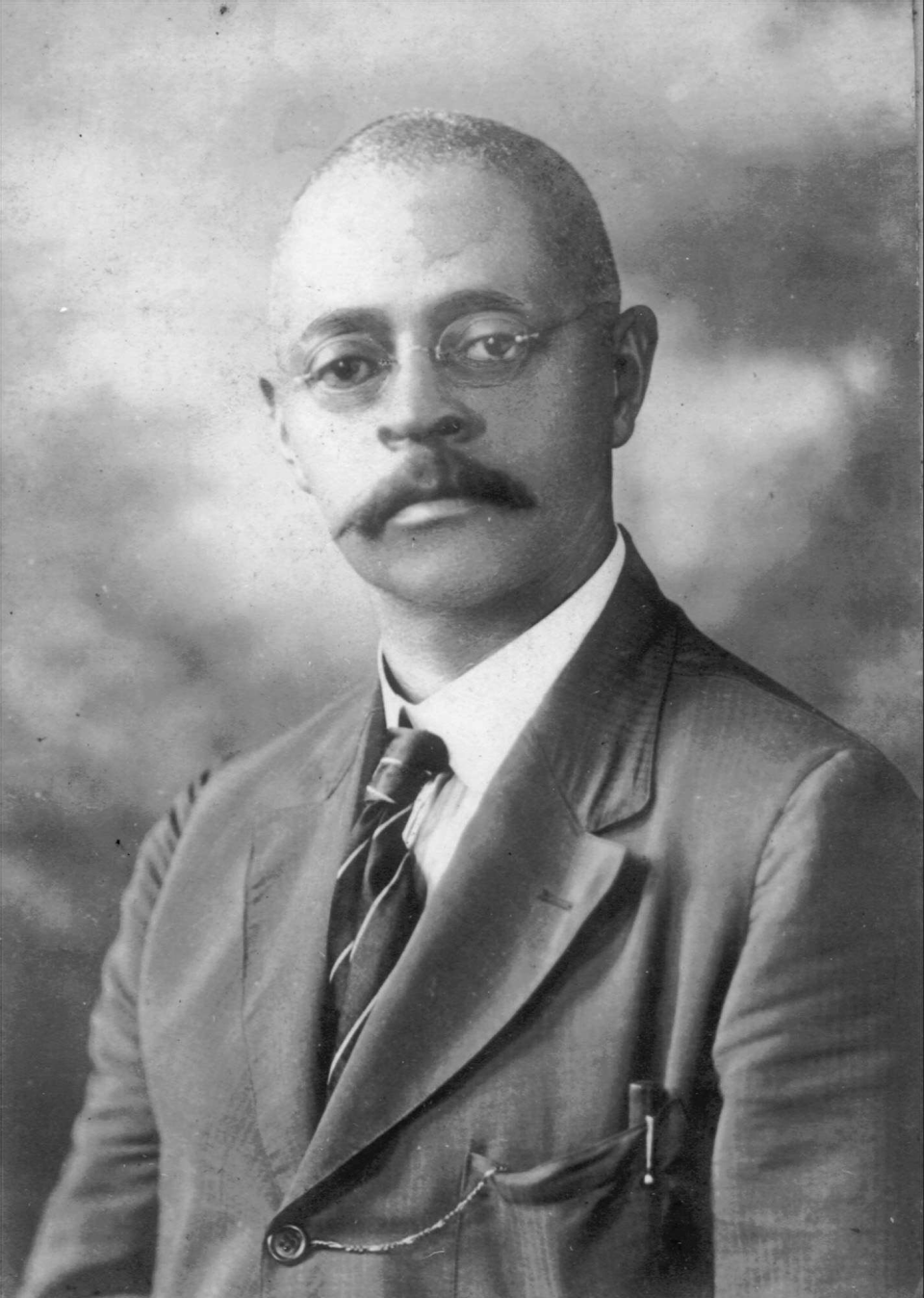

Thomas Leroy Jefferson (1867-1939)

He made history as the first Black physician in West Palm Beach.

Born in Mississippi to the son of a prominent cotton grower, he was rumored to have connections to President Thomas Jefferson through the slave Sally Hemmings.

After initially teaching and running a drugstore in Louisiana, Jefferson pursued medical education in Texas and later practiced in Texas and New Orleans. Around 1900, he relocated to Palm Beach, establishing his medical office in the Black community known as the “Styx.”

By 1912, Jefferson and other Black residents had moved to West Palm Beach. Renowned for his cycling habits, he earned the moniker "bicycle doctor" while serving the community with a medical office on North Olive Avenue and a drugstore at Clematis Street and Rosemary Avenue.

Solomon D. Spady (1887-1967)

Hailing from a Virginia farm and graduating from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, he was affiliated with the New Farmers of America and garnered attention from prominent Black figures of his era, including agricultural chemist George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington of Tuskegee Institute.

In 1922, at Washington's recommendation, Spady became a teacher and the principal at Delray County Training School, a position he held for 35 years. Under his leadership, the school expanded and, in 1937, transformed into George Washington Carver High School.

Known affectionately as "Prof" Spady, he taught woodshop and agriculture, guiding his students to championships and instilling valuable skills for community engagement.

Following his retirement in 1957, Spady's legacy endures in the form of S. D. Spady Elementary School, housed in the building where he once served.

His residence, a Mission Revivalist-style home at 170 NW 5th Ave., now the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum, was a pioneering household in the West Settlers neighborhood, boasting indoor plumbing, a telephone, and electricity.

Louise Elizabeth "L. E." (Baker) Buie (1914-2003)

The Georgia native moved to West Palm Beach as a child and, forced to abandon high school to support her family, she embarked on a lifelong commitment to aiding others.

In 1937, she became a member of the local branch of the NAACP, advocating for desegregation of whites-only beaches and initiating a series of social justice causes. Serving as president of the local NAACP from 1954 to 1968, and later as president emeritus, Buie balanced her activism while working as an insurance agent and home healthcare nurse's aide.

During the 1960s, she played a pivotal role in challenging the exclusion of Black history from textbooks in Palm Beach County schools, ultimately succeeding in introducing a Black history course.

Buie's tireless efforts extended to combating segregation in various institutions, participating in civil rights marches, including the historic 1963 March on Washington.

Following her death, the Florida Legislature honored her by designating the Skypass Bridge in Riviera Beach as the L. E. Buie Bridge. She received other accolades, including the co-naming of the Urban League building in West Palm Beach.

Spencer Pompey (1915-2001)

In 1942, he and two fellow Black educators in Florida initiated a landmark class-action lawsuit against the Palm Beach County School Board and its superintendent.

The legal challenge, aimed at rectifying the $25-per-month pay discrepancy between white and Black teachers, was successfully championed by then-NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who later became a Supreme Court Justice.

Beyond the courtroom, Pompey also played a pivotal role in desegregating Delray Beach's whites-only beach during the 1950s and advocated for the establishment of the city's first organized recreation programs for Black children.

Serving as a coach, social studies teacher, and principal at the all-Black Carver High School in Delray Beach, Pompey and his wife Hattie Ruth, an esteemed educator herself, left an indelible mark on the educational and civil rights landscape of Florida.

After Spencer's passing in 2001, Hattie Ruth published his manuscript, titled "More Rivers To Cross."

Eva Williams Mack (1915-1998)

Arriving in West Palm Beach in 1948 with a nursing degree, she was the first health specialist for what would become the Palm Beach County School District.

She later joined the Palm Beach County Health Department in 1950.

Mack played a pivotal role in shaping statewide student health, introducing curricula on sex education and substance abuse, and advocating against the expulsion of pregnant students.

In 1979, she founded the Sickle Cell Disease Foundation of Palm Beach County, and in 1982, she became West Palm Beach's first Black mayor, serving two terms.

Frank Malcolm Cunningham Sr. (1927-1978)

Born in Plant City, Florida, he overcame racial barriers to become a trailblazing figure in the legal and civic landscape of West Palm Beach.

Attending Florida A&M University and facing segregation in Florida's law schools, he pursued legal education at Howard University.

In 1953, he established the first Black law practice in West Palm Beach, later joined by his brother T. J. Cunningham.

Cunningham made history in 1962 as the first Black person elected to public office in Florida since Reconstruction, serving on the Riviera Beach Town Council.

He also was the first Black city attorney for Riviera Beach, was an advocate for school desegregation, and co-founded the first minority-owned commercial bank in Florida, First Prudential Bank, in 1973.

His legacy is commemorated by the F. Malcolm Cunningham, Sr. Bar Association and Cunningham Park in Riviera Beach.

Joseph N. Bernadel, (1947- )

Migrating from Haiti in 1975 after completing his education, he served as a major in the U.S. Army for 22 years, holding key positions worldwide, including in Haiti and Mozambique, earning accolades such as the Legion of Merit award.

Bernadel, with a B.S. in Administration from the University of Hawaii and a graduate degree in Latin American and Caribbean Affairs from the University of Florida, is multilingual.

He made history as the first person of Haitian descent to establish a public school in the U.S., the innovative Toussaint L’Ouverture High School for Arts and Social Justice in Delray Beach (now in Lake Worth Beach).

He represented the Haitian diaspora in the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) after the 2010 earthquake.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Historical people who redefined Palm Beach County Black history