Black History Month: Tennessee Unionist paves financial path for Black residents in Columbia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor's Note: This article is the first in a series of stories related to the Maury County African American Heritage Society's theme of "Democracy in America" during Black History Month, exploring Black history in Maury County.

The transitional period from enslavement to emancipation is a complex topic in Middle Tennessee. Right here in Maury County, the complexity was everywhere.

There are stories of the enslaved who escaped and became national leaders for civil rights, and others who stayed after emancipation and continued to work and live on the same plantations as free people. There were white citizens who were the “typical” slaveholders, while others enslaved no one.

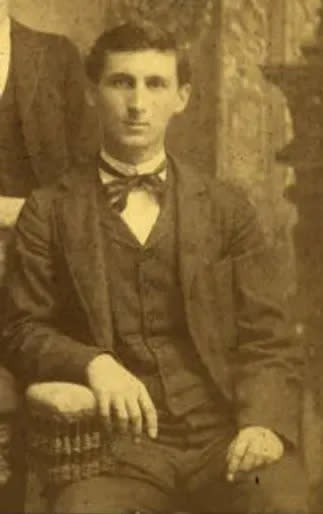

Samuel Mayes Arnell makes impact in Maury County

There were even those who were enslavers who embraced the Union. How does that make sense? Study Samuel Mayes Arnell. He was born and raised in Maury County, Tennessee into a slaveholding family from the Zion Community. Yet, it can be argued that no one did more for the newly emancipated in Tennessee than Arnell. His greatest legacy is that he used his political influence to help the formerly enslaved to help themselves on the road to proper citizenship.

Arnell was born in 1833. His father was the minister at Zion Presbyterian Church. After attending Stephenson Academy and Jackson College locally, he was admitted to Amherst College in Massachusetts.

Upon graduation, he returned to Maury County, studied law, and was admitted to the Maury County Bar in the early 1850s. By 1860, he had six children, owned property valued at some $15,000, and enslaved four men between the ages of 24-30 years old.

As the country began to split over States’ Rights and the extension of slavery, Arnell’s own conviction remained pro-Union, a not-uncommon viewpoint to most of those who lived in Maury County as late as 1860. His attachment to Union had little to do with the great political debating points of the day, and more about his own family tradition. Both of his grandfathers had fought in the American Revolution.

Arnell wrote, “It occurred to me that I owed it to my family to make some public addresses for the Union and so I did. ‘Go and do it,’ said the strange impulse within me. ‘Everybody is talking politics! Go out and proclaim your conviction,’ said the voice. The talk of giving up America, to me, seemed like looting a part of this inheritance, much more valuable than riches…so I decided to do what I could to oppose it.”

Arnell began giving speeches around the county stressing President Lincoln’s constitutional election and the benefits of remaining in the Union. He reasoned that his slave-owner status could calm local fears and persuade voters to oppose secession.

When Fort Sumter was attacked, however, most pro-Union sympathy in Maury County went along the wayside, and it wasn’t long before Arnell found out that his Unionists sentiments were in the vast minority, and he started receiving threats against his life and property. He became an unpopular figure in his own town…even his church, which his father had led and he himself had attended since his birth, preached pro-secession ideas from the pulpit, and he left friends and faith behind.

With the coming of the war, life became dangerous for everyone in Maury County, but as a vocal Unionist, it was particularly so for Arnell. Tragedy came to his family. Arnell’s brother and ward, William, a University of Virginia graduate and fellow attorney, joined the Maury County Braves, a Confederate cavalry unit of which he served as “3rd lieutenant.” In 1863, young William came home on sick leave, and died at Samuel’s home from his illness.

Escape from Confederacy

In July and August of 1864, guerilla bands ransacked Arnell’s home, stealing food, livestock, and other goods. In November of 1864, Arnell’s home was near the front line of fighting as Gen. Hood’s Confederate Army maneuvered around Union Gen. Schofield’s troops. The Arnells fled their home and were brought within the Union lines for safety. As the Confederates overran the Union position, Arnell fled to Nashville, while his wife traveled back to their home. There, she found their house had already been ransacked by the Confederates.

A Confederate colonel asked where Arnell was, his wife refused to reply, to which the colonel retorted, “If I could have caught your husband I’d have hung him to the tree out there. The neighbors told me all about him, what a traitor he is to the South, how from the beginning he plotted, informed and helped the Yankees.”

Befriending Military Governor Andrew Johnson in Nashville, Arnell was tasked with raising a regiment of mounted infantry for the Union, but Arnell was taken sick and remained in bed for three months. During that time, his young daughter died, presumably from exposure, while fleeing from their home.

The hardships he and his family endured, prompted him to political action. Arnell was elected to the Tennessee State Constitutional Convention in 1865.

Andrew Johnson, who was now vice president of the US, worked with President Lincoln to bring Tennessee back into the fold even before the war officially ended. They began to identify unconditional Unionists who might become political leaders to make sure secessionists would not retake control of state government. Those picked would have to be for the immediate abolition of slavery and a schedule to declare all acts of the Confederate government null and void.

Arnell enters the legislature

Radical Republican William G. Brownlow was elected governor, and Arnell was elected to the state legislature. Arnell declared, “Maury County gave me then, as she always did afterwards, a fair and honorable support at the polls.” He represented Williamson, Maury, and Lewis Counties.

Arnell’s most significant legislation was the Franchise Bill of 1865, which stipulated that only men loyal to the Union from the beginning of the war, loyal citizens from other states, or persons who had become twenty-one since March 3, 1865 could vote. Others had to prove their loyalty and have two witnesses vouch for them. Confederate government officials, military officers, and individuals who had assisted the Confederacy were disfranchised for fifteen years. Confederate soldiers were forbidden to vote for five years. His bill became law June 5, 1865.

In 1866, Arnell drafted legislation to allow city corporations to establish public libraries and was considered Tennessee’s “Father of Public Libraries”

The first test of the new franchise law came in the August Congressional election of which Arnell was a candidate for U.S. Congress. Arnell lost his election, but the governor felt a sense of duty to the author of the Franchise Act, and threw out the election results in several counties, including Maury, for “illegal registrations and/or improper voting,” and seated Arnell instead.

Congress denied seating the Tennessee delegation until the state was readmitted to the Union, which required ratification of the 14th Amendment, and called for extending equality to blacks and prohibited persons who had aided the Confederacy from holding any state or federal office until Congress removed the provision. When conservative members of the legislature refused to show up for the vote, Arnell called for two of the members to be arrested, had them returned to the House chamber, and counted as “present,” thus passing the 14th Amendment. Tennessee officially rejoined the Union and Arnell went to Washington.

Arnell continued to uphold his Radical Republican viewpoints and took it even further. Not only was he for disfranchising former Confederates and Confederate sympathizers, but he called for black suffrage as well as giving blacks the right to testify in state courts. In 1866, black Congressman James Rapier expressed to Arnell the gratitude that black citizens had for the legislator.

Right to vote passes

Tennessee’s bill granting freedmen the right to vote passed on February 25, 1867. Arnell’s role in these radical changes made him a marked man. He received threats from various groups including the Ku Klux Klan. They were often seen riding in Maury County, intimidating blacks and Unionist whites. Their tactics worked, and African Americans, out of fear, refused to notify the Freedmen’s Bureau about the depredations, giving the false impression in Washington that all was well in Maury County.

In June of 1868, knowing that Arnell was heading home to Columbia from Washington, Klan members with pistols and rope boarded a train they believed he was on, ready to kill him. Luckily, for him, he was on another train. Arnell notified the governor and the governor eventually called for martial law in several Middle and West Tennessee counties. In fact, a group of African Americans regularly followed Arnell home to ward off possible assassins.

Arnell took the fight against the Klan to Washington, where he opened federal investigations into their actions. He also fought to sustain the power of the Freedmen’s Bureau, citing “In Middle Tennessee, the only guardian for these colored people that is capable of ferreting out these outrages and bringing them to public notice is the much abused bureau.”

Arnell founds Freedmen's Bank, fights for rights of Black Tennesseans

Arnell, along with James P. Baird chartered the Freedmen’s Bank branch in Columbia, one of only four in the state. The bank was commissioned to help the newly freed to begin saving and investing money for their futures.

In the election of 1868, new black voters were being threatened and coerced in Columbia. Arnell stepped in and led a massive group of black men to the polls at the courthouse, and made sure they voted.

The state and congressional elections of 1870 saw a sweep of conservative wins. The radicals lost control of the state, and Arnell left politics. With the change, new laws came in that restricted blacks from enjoying many of the freedoms that came with true citizenship. In Columbia, “black codes” forced many African American businesses out of the downtown square and to the East side of the city.

'Father of Maury County Schools'

Arnell remained in Washington for a few years, where he practiced law. He returned to Columbia and from 1879-1885, he served as postmaster.

He focused much of his time on improving education. He was appointed one of three school directors for the county and was elected Superintendent of public schools from 1885-1888. He was hailed in newspapers as the “Father of Maury County Schools.”

Arnell eventually moved to Johnson City to be near his daughter as his health failed. He died there in 1903.

Despite his great unpopularity in his own community, Arnell stood by his convictions and fought for his beliefs. He never regretted his decisions. Rather, Arnell thanked God that He “permitted me to live between the years 1861-1871; permitted me to be an eyewitness to that most magnificent period of human advancement, when a great nation was not lost, but saved – rebuilt on better foundations.”

Tom Price is director of the Maury County Archives. Jo Ann McClellan is the Maury County Historian.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Herald: Tennessee Unionist paves financial way for Black residents in Columbia