This Black Iowan saved hundreds of soldiers in WWI. Should he have received a Medal of Honor?

The bodies of his friends, men he’d grown to call brothers, lie just out of reach, twisted and mangled amid the battlefield’s muddy sludge.

Every pause in the machine guns’ violent hail allows the wind to carry the screams of those still alive. Grown men begging for their Gods or their mothers or their homes, an ocean and a world away. Their pain is almost as palpable as the haze of mustard gas lingering in the trenches, slowly eating at their fellow soldiers’ skin.

More than 100 Black American soldiers have fallen in the chaos, adding to an already high body count from the past few days of offenses. And more are coming over the top every second.

It is a massacre. A nightmare made real.

After months of grunt work building roads and patrolling towns, 2nd Lt. Rufus Jackson — a boyish-looking Black 22-year-old who’d forgone his senior year at Iowa State College to join the American effort in World War I — has spent the past few days being christened into combat.

With the thunderous boom, boom, boom of shells rattling his men’s bones day and night, sleep comes in short spurts — if it comes at all. Same with supplies. Water is gone. Rations, too. Most sustain themselves on bread baked with sawdust for mass and brought haphazardly to the front in rucksacks.

Now ammunition is running low.

But their orders are clear: Keep moving forward.

Coordinated attacks by French and American forces have pushed the Germans back to their line, entrenching them in camouflaged, reinforced nests scattered across the front. Their positions are so fortified French cables declare them impossible to take.

Like a predator returned to its cave, the Germans have the upper hand — and the high ground.

The French requested this final push start after dusk at 9 p.m., giving them enough time to resupply and reset. But Col. Thomas A. Roberts, a white officer placed above Jackson’s unit, sent his Black soldiers into the breach at 9 a.m., a full 12 hours early.

Roberts doesn’t believe African Americans belong in the service, as his writings later reveal. If they are going to be in the military, he seems to think they’re best used as cannon fodder.

And so it is. More of Jackson’s men enter the theater; more bodies lie in sludge.

Jackson leads a mortar unit. To stop the bloodshed, he has to silence the guns. If he can deploy his bombs correctly, he may break up the German line, may provide cover for his charging men.

But to ferret out where the machine gun nests are, Jackson has to get closer. Much closer.

His next decision would change the course of the battle, and, in a small way, the course of the war. Going above and beyond the call of duty, Jackson would save hundreds of lives — and irrevocably shatter his own.

So why wasn’t Jackson awarded the Medal of Honor?

One Iowan believes he can prove Jackson was discriminated against in a well-documented effort by white officers to disparage and diminish the efforts of soldiers of color after the Great War.

He’s determined to give Jackson’s service a new ending, to right more than a century of injustice.

And, in doing so, rewrite his own story, too.

'One and only shot' to correct history

Rufus Jackson is one of many men who live in Josh Weston’s head, their lives playing in his subconscious like old movies.

Their stories come to him in quiet moments: when he’s falling asleep, or when he’s driving to work at the Valor Medals Review Project before the world has woken up, the only sound the snoring of his service dog, Moscow.

There’s Cpl. Isaac Valley, a Black man who was severely wounded when, instead of taking cover, he jumped on a grenade in a trench of soldiers, saving dozens.

And Pvt. Sing Lau Kee, an Asian American who, despite steady mustard gas attacks that paralyzed his commanders, refused evacuation and single-handedly kept a message relay center running, and troops moving, for 24 hours straight.

And Mjr. Julius Adler, a Jewish American from the Ochs family, publishers of the New York Times, who, while corralling German POWs, came upon a party of 150 enemy soldiers. Running toward them with his pistol raised and screaming for their surrender, he captured 50 more.

These soldiers moved in separate orbits, coming home, carrying their service on their shoulders like an invisible boulder. They were connected by America’s first forgotten war, but living in bell jars, using the experience as either fuel for a full life or disappearing into themselves, the consequences of what they saw rattling around in their minds like balls in a bingo cage.

But a century later, their stories collide with two questions:

Were the medals for their heroic acts of valor downgraded solely because of their race, ethnicity or religion, as was common in America’s 20th century military?

And, can Weston, 32, employ the weight of historical forensics to muster enough proof that these men deserve to be awarded the Medal of Honor?

For nearly three years, Weston and his colleagues, Ashlyn Weber and Timothy Westcott, have researched the actions of more than 200 World War I soldiers — African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, Jewish Americans and Native Americans — who may have been discriminated against.

While the military has conducted reviews of valor for World War II and all subsequent conflicts, their work marks the first — and, with funding for such endeavors increasingly scarce, likely the last — review of World War I service members.

“This is the one and only shot that these service members will ever have to get the attention that they deserve,” says Weston, the project’s senior military adviser.

The team has until 2025 to complete its congressionally sponsored, privately funded analysis and submit its medal recommendations to the Department of Defense, which will make final determinations. That process could take years as nominations work their way through the ranks, and any person along the way could decide a particular soldier doesn’t meet the subjective qualifications of the Medal of Honor — that a recipient “distinguished himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

“Our entire purpose is to gather up as much information objectively, almost like a court case,” Weston says, “where we provide the evidence to say, no, this person does deserve the Medal of Honor, and the Department of Defense, sorry, but you guys got it wrong.”

A cup of black Panera coffee in hand, Moscow satiated with treats, Weston turns on his computer and settles in. It's another morning of plotting days of engagements and laying out hourly if not minute-by-minute timelines to prove that these men committed the ultimate selfless act for the sake of their comrades, the sake of their country.

Growing up in an abusive environment in the Quad Cities, Weston never had the tools to deal with the anger and anxiety that flowed through him. A jock, he was a member of the football, hockey, track and tennis teams, but wasn’t ever the star player. That was fine with him. He preferred the background. Preferred quiet. Preferred the past.

Studying history became an escape. “I was basically a hermit,” he says.

Pairing a childhood of slick, glossy Army TV commercials — Be all you can be! An Army of One! — with a nascent interest in being a cop, he joined the military police after graduation and was stationed at Fort Campbell.

Like most law enforcement officers, Weston had to balance seeing the worst in people, taking in all the violence that some are capable of, with offering a hand, a bit of peace of mind, when people were most in need.

He investigated murders; saw a person get shot and killed. He lost a childhood friend in the service to suicide, then a member of his unit, too, someone he’d just worked with a few nights before, passing the time by commiserating over their mental health struggles. The man had a wife, pregnant with their second, a child he’d never meet.

Slowly, the bad outweighed the good; all those scenes, all that dark underbelly hit him “really, really hard.”

He wasn’t sleeping. He’d either shut down completely, lost inside his mind, or erupt with fury, flying off the handle like “a monster.” He was diagnosed with chronic depression and social anxiety disorder. He tried to self-medicate with alcohol.

“I was hateful towards life and what it was throwing at me,” he says. “Not only was I not a nice person, but I just wasn't a logical person.”

Medically discharged, he came back to Iowa, searching for purpose. He took odd jobs, whatever could pay his few bills. Bounced around.

He was lost, again. Damn near homeless, he says. And wondering why everything felt like a fight.

His wife and a move to Kansas City helped calm him. The birth of his two daughters did, too, but they also pushed him to figure out how to bring meaning and hope from a tough start, a heritage they’d be proud of.

Then he drove by an odd, old home with a banner: George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War.

Jackson answers call to serve

Jackson sets out from the trench on his belly; the flatter he can make himself, the less time out in the open, the better his chances of survival.

The battlefield’s ground is more stew than solid. Days of rain filled impact holes with standing water and amplified the smells of war: gunpowder and gasoline and rotting corpses.

As he crawls over matchwood — sharp fragments left by exploded trees — the earth shakes with bombs, and the air buzzes with machine gun bullets. He’s got several hundred yards to go, but each foot is like running a marathon on a wet beach.

He moves inch by inch, ever closer to the bodies of his friends — and to the ear-splitting screams of those still alive.

Falling back would be easy, so easy, but Jackson had been raised to serve his country.

His father, John Jackson, who was born before the Emancipation Proclamation, was a member of the famed “Buffalo Soldiers” unit serving on America’s western frontier. After years following John’s military postings from Wyoming to Missouri, the Jacksons finally found some permanence — and prominence — in Des Moines.

The only child of John and his wife, Mary Jane, Rufus Jackson moved among the city’s Black elite from an early age, speaking often at the Des Moines Negro Lyceum, a roving salon where Black Iowans discussed culture and municipal happenings.

Jackson was a star debater at East High School, and his classmates selected him for a distinguished position on the school’s Quill yearbook staff. It was an honor that “should not be regarded lightly,” wrote The Bystander, a newspaper covering Black Iowans, and “a testimonial to his ability as well as affability.”

Jackson received a four-year scholarship to Iowa State College, where he continued to debate. In his first semester, he took fourth place in the state speech contest, the only Black competitor in a field of mostly juniors and seniors.

Little more than a month after America declared war on Germany in April 1917, Jackson enlisted and was appointed a sergeant in the hospital corps of an all-Black regiment out of Illinois. In October, his men were shipped to Camp Logan in Texas for training.

By February, Jackson was promoted to second lieutenant, and a few weeks later, he tied the knot, marrying Texas native Leona Miller.

Jackson “has received more honors and faster than any other of the many Iowans that we have gone to this war,” The Bystander wrote.

“We hope that there is still greater things in store for this worthy young boy.”

A few weeks later, Jackson, then 23, commanded 149 men on a ship headed to France.

'A braver bunch of men never got together'

Just as Jackson and the nearly 400,000 other Black soldiers crossed the Atlantic, so did America’s racism, says Timothy Westcott, director of the Robb Centre and a Marine Corps veteran.

Due to American troops’ segregation, Black units were placed under the French Army’s purview. Soldiers had to immediately trade their highly accurate American rifles for the markedly worse French version. The guns required different caliber bullets, different replacement parts. And with already strained supply lines, the French couldn’t ensure they’d get American goods.

Those same supply strains meant the French also couldn’t replace the broken gas masks, binoculars or heavy wire cutters Black units had been given — if they’d been given any of those at all.

“These individuals were fighting for a country that didn't even want them,” Weston says. “That's the simplest way to put it. But they fought anyways.”

Even if Black units were allowed to retain their leadership — as Jackson’s 370th was — white American officers often filled out the layers between boots on the ground and a French general.

In the case of the 370th, that white American was Col. Roberts.

While Jackson crawled, casualties continued to mount in the assault Roberts called for 12 hours early. With hell breaking loose, the colonel requested Capt. John T. Proust, a chaplain on the front with Jackson’s men, come to headquarters.

Col. Thomas A. Roberts: These men are a bunch of cowards. The officers are no better; they don’t seem to have any spirit, they don’t shout when they go over the top.

Capt. John T. Proust: I don’t know what you have in mind Colonel, but I do know that a braver bunch of men never got together. Does the Colonel know that we have lost a hundred men a day and have been up here over a week?

Col. Thomas A. Roberts: Well, that’s what soldiers are for, to be killed and wounded.

— Conversation recorded in the memoir of a 370th soldier

Later, when the French general questioned Robert’s actions and the unit’s heavy losses, he blamed one of the Black officers.

“Any chance that he could get, he would blame an African American for something that went wrong,” Weston says. “He does not care about the life of these men, these humans. He doesn't care because they're a different color.”

But Roberts was far from the only one. In their papers or memoirs, other officers described Black soldiers as failures and inferior fighters; one even wrote to a powerful senator that they were “dangerous to no one but themselves and women.”

Those beliefs were normalized in a 1925 Army War College report on the future use of Black soldiers, which called them “subservient,” “of inferior mentality” and “inherently weak in character.”

The racism of the time bleeds out in less obvious ways, too. The disability reports that project members read always seem to place Black soldiers just under what they need to get full benefits. The boxes Weston requests at libraries or archives always seem to come covered in a thick layer of dirt and dust — grime making tangible the truth that these files haven’t been looked at in years.

“You see firsthand the blatant racism, the blatant prejudice. It becomes an everyday thing,” Weston says. “This isn't off in some foreign, distant land. This is here. This is in our lives, and whether or not we like it, we have to accept it, and we have to do something about it.”

“Hate won’t stand,” he adds.

No Black man was awarded the Medal of Honor in the years after the Great War, a pattern that held for WWII until a similar review in the 1990s led to seven Black men being granted the military’s highest honor.

Although two Black WWI veterans have now been posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor — Cpl. Freddie Stowers in 1991 and Pvt. Henry Johnson in 2015 — Westcott believes many more are worthy of the honor, which his team hopes to be part of bestowing.

“As a veteran, it is my duty to make damn sure we do the best that we can do to see if they warrant any further and long, long overdue recognition by our nation,” he says.

We don’t leave men behind, Weston adds. And “valor never expires.”

At the beginning of their work, Westcott made a phone call to a surviving relative of a service member, one he still thinks about often. He told her what he was doing, what the purpose of the review was, and the line went silent. He worried whether she’d hung up, whether they’d been disconnected, but then a hoarse voice finally spoke.

“It's taken 100 years for this phone call.”

War ends, but the fight marches on

The Germans' heavy barbed wire made rapid advance difficult on the best of days, and with buckets of rain and fog and chills, this was far from the best of days. Jackson crawls under each strand, careful of the impossibly sharp edges waiting to cut into his fatigues or his skin.

Close enough to the line, Jackson observes the Germans’ fire for just as long as he needs to determine their movements and targets.

Then he crawls back the same hazardous route. Falling into impact puddles. Minding matchsticks and wire. Past his friends' bodies, past the screams of those still alive.

Back to the trench.

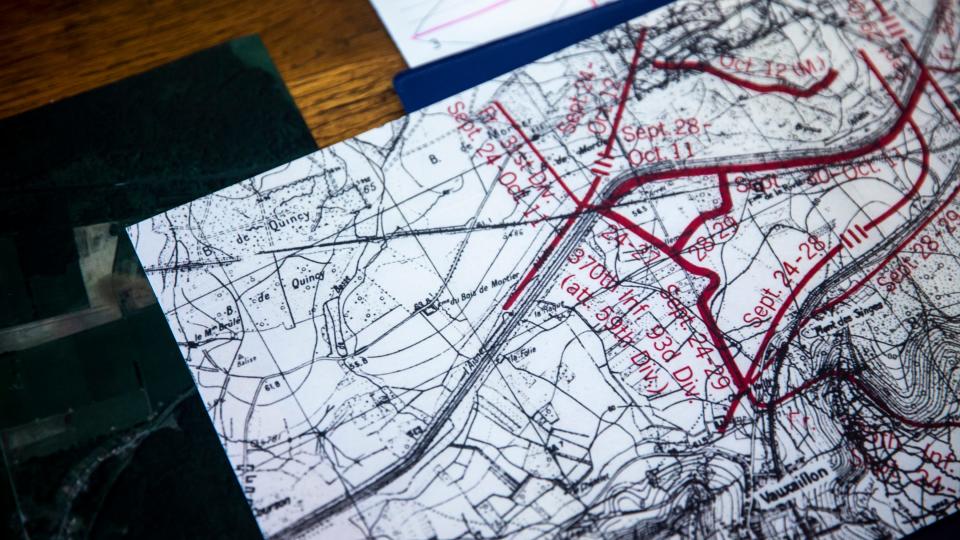

Able to direct his men to the locations he scouted, they blast off mortars, silencing the guns one by one. Now his brothers going over the top have a chance, and they continue to push forward, driving the Germans farther and farther east.

A few hours later, Jackson and his men break the German line and take the nearby towns — and the high ground.

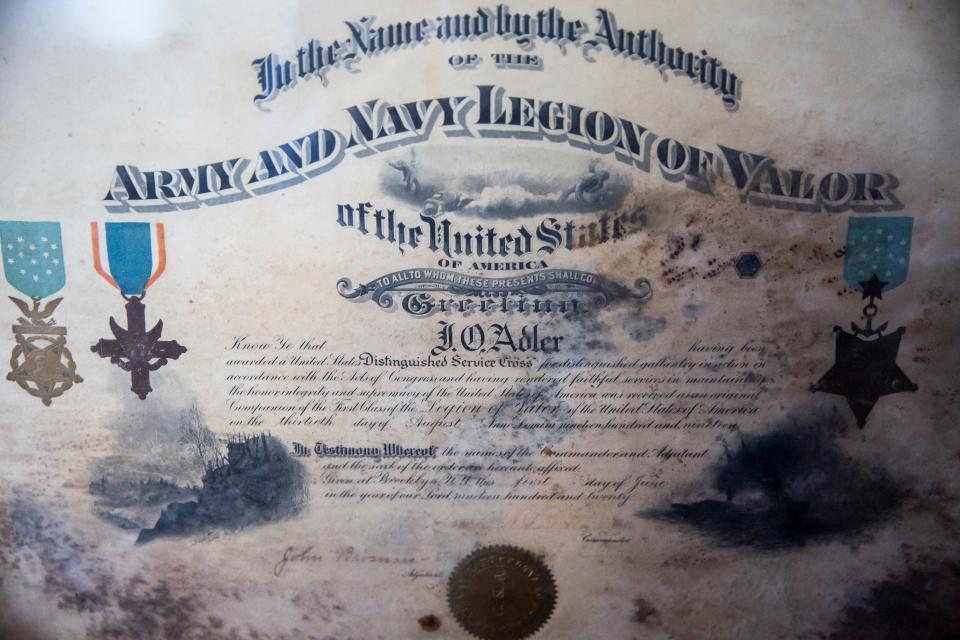

For his actions that day, Jackson was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, one step below the Medal of Honor.

But because Jackson’s actions were selfless, heroic and “absolutely vital” to the success of the operation, there’s no doubt in Weston’s mind that his medal should be upgraded.

“Without him stepping up and doing what he did, they wouldn't have been able to move forward,” Weston says. “If it wasn't for his mortars, the machine guns would have continued to fire, and it would have been the same result as they had seen throughout the entire day.”

Jackson and his men kept fighting for the rest of the war, pushing Germans east hundreds of kilometers to the Belgian border. When the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month came and the armistice went into effect, Jackson was still in the thick of the battle.

Just before Christmas Eve, Jackson and his men landed at the same French port where they’d arrived. Once starry-eyed recruits, now battle-hardened front-liners, they were heading back with just half of the men who’d come over.

“Our Christmas will be more or less one of the mind, which after all is perhaps the best way to observe it,” Jackson wrote in a letter to a friend. “It is our hope that those whose loved ones will not return will find consolation in knowing that the world is better because of their sacrifice.”

He was leaving battlefields behind. But the rest of Jackson’s life would still be a fight.

An overdue reach across centuries

Jackson was honorably discharged less than a month after arriving home. While other returning soldiers received ticker tape parades down grand avenues or medal presentations attended by thousands, Jackson’s welcome back to Des Moines was muted.

The city’s Black elite hosted him for receptions, and he spoke at a few churches. His Distinguished Service Cross for “extraordinary heroism” was sent to Camp Dodge, where a presentation ceremony was planned, according to a Register report at the time.

He and Leona lived at his parents’ east side home for a few years. A short blurb in The Bystander says he was preparing to resume his studies, but the 1920 census lists him as a janitor at a print shop.

In the decade that followed, Leona and Rufus divorced, and he moved to Chicago with his mother, taking a job on a farm. Leona never remarried, dying of pneumonia in 1964. By 1940, Rufus was in Detroit. After spending at least a year unemployed, he got work through the WPA.

From there, he vanishes, a ghost of his previously vibrant life, Weston says. He never seems to remarry, and he dies without children.

“Prior to the war, he was very successful,” Weston says. “He was well educated. He was a prominent figure in the sense of what an African American was allowed to be at that time. He fights in the war, he comes back, and he's just a completely different person.”

“He becomes a hermit, and he doesn't just want to be a part of the society that he once contributed to.”

For Weston, a day’s worth of reading racist history and learning how these men’s lives were irrevocably changed elicits a lifetime’s worth of emotions: “anger, embarrassment, camaraderie, gratification.” You want to scream and cry and laugh all at the same time, he says.

But doing this research has become the purpose of his life, the tool he needed to deal with his anger and anxiety. These tentacles of compassion have reached other parts of his life, too. He’s become a better father, a better community member; this summer, he hopes to donate a kidney to a stranger.

“I came here, and it's like all the puzzle pieces came together,” he says, “all the strife that I've been through, all the dirt that I've had to crawl through, it all made sense.”

For Weston, it’s this work thatwill rewrite his story, leave a new legacy for his girls.

“I want them to know that their dad did something that was meaningful,” he says. “I want them to know that it's OK to give your all to other people. We live in a world that's scary. There's bad people, but there's good people, too. And we can be those good people.”

More: Inside the George S. Robb Centre's Valor Medals Review Project for World War I soldiers

Weston guards himself from thinking too much about what will happen if any of his research is successful. Realistically, out of 200 men, only a few will earn the honor — if any.

Whatever happens, the Valor Medal Review team will “keep fighting for these guys,” he says, and find a different way to honor these heroes.

As much as the lives of the men he researches live in his head, Jackson’s story is the one Weston can’t shake.

In a time where institutional racism was a powerful current beating Black men back, forcing them to bend, Jackson fought the tide to attain extraordinary accomplishments: He went to college, he became a prominent figure, and he was an officer in the United States Army.

“This guy faced a lot of adversity, and yet he still just kept on keeping on,” Weston says. “That speaks to my soul.”

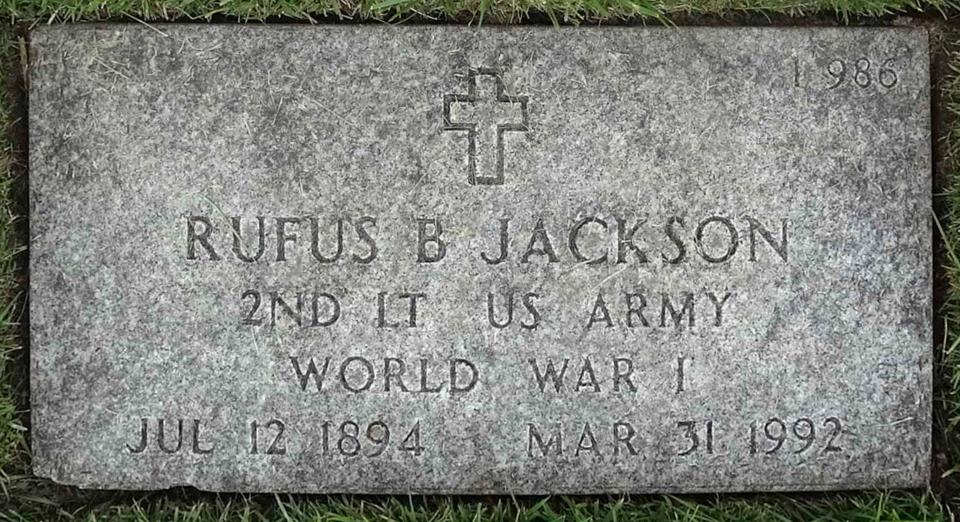

The last public record of Jackson is a photo of his small headstone at Fort Custer National Cemetery in Augusta, Michigan. Flat to the ground, as flat as he was the day he crawled to enemy lines, the marker lists meager facts: his rank and the date of his death, March 31, 1992, the ultimate finality chiseled into rough stone with an obscurity to match the end of his life.

But reaching across centuries, Weston hopes to bring Jackson out of seclusion, to recognize greatness and bravery that is long overdue.

Just like his own, the ending of Rufus Jackson’s story is yet unwritten.

Courtney Crowder, the Register's Iowa Columnist, traverses the state's 99 counties telling Iowans' stories. Her grandfather Harold Crowder served as a physician in the World War II era and her grandfather Chester Care was in military intelligence during the Korean War. Reach her at ccrowder@dmreg.com or 515-284-8360. Follow her on Twitter @courtneycare.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Why didn't Black soldier get Medal of Honor for saving lives in WWI?