Black Knoxville men worked tirelessly for the Civil Rights Act of 1875 | Opinion

I am truly amazed at the second group of Black men of Knoxville and others across the state as they fought for the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875. They followed the first group of men like Melvin J.R. Gentle and William B. Scott, who were in the forefront in the late 1860s. Local newspapers covered their efforts for the legislation and printed editorials against it. Its eventual passage led to a spate of Southern legislatures passing laws to nullify it.

The second movement began in Knoxville at the Knox County Courthouse on April 3, 1874, with a group of Black citizens selecting delegates to attend the civil rights convention in Nashville that would convene April 28. The meeting was called to order by 30-year-old William F. Yardley, who had become Knoxville's first Black lawyer three years earlier. The Rev. William Howell, pastor of Mount Olive Baptist Church, was named chairman.

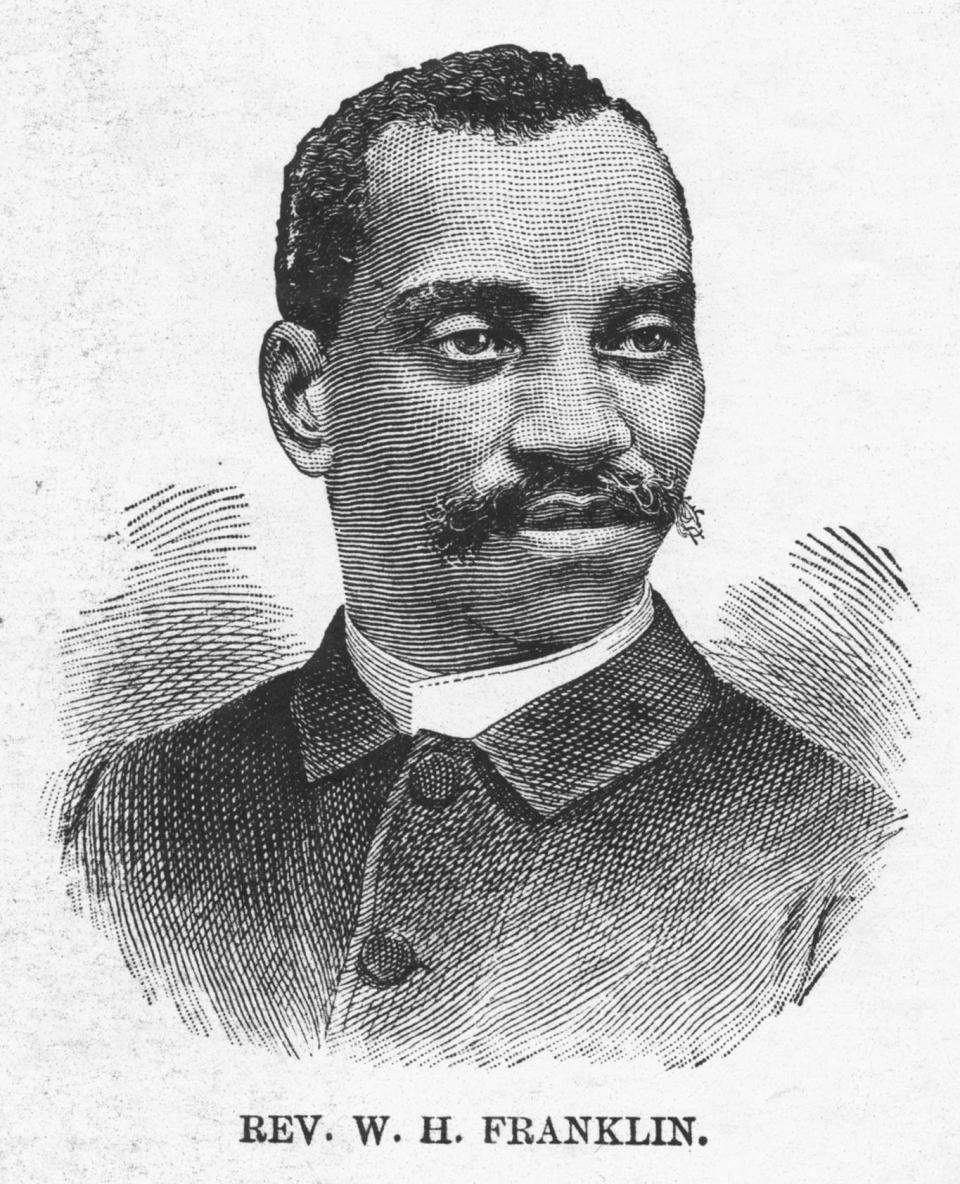

The Rev. George Washington LeVere, pastor of Shiloh Presbyterian Church, became the vice chair. Twenty-two-year-old William H. Franklin was named secretary. He would become the first Black graduate of Maryville College six years later in 1880.

LeVere explained the reason for the meeting, and he and three other attendees appointed the delegates for the convention. A finance committee that included all the pastors of Black churches in Knoxville was appointed. Another committee was appointed to work with railroad officials to secure half-fare transportation to and from the convention.

Hear more Tennessee voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought-provoking columns.

During the second day of the meeting in Nashville, Yardley was called upon to lay out the purpose of the convention, and he immediately challenged the limitations placed on Black citizens by the Tennessee Constitution of 1870, which forbade mixed marriages between the races.

He decried the unequal school system for Black students. "Colored people should be granted the privilege of going to places of amusement and sitting where the white people did, not in the galleries to be scoffed at by little boys and girls," he said.

Several newspapers were quoted on the issues in the May 7, 1874, issue of the Knoxville Press And Herald. The Morristown Gazette said: "They should let civil rights and well enough alone. They make it an issue that needs to be met squarely and fearlessly, and we doubt not it will be the whole Caucasian race, irrespective of party."

The Nashville Banner said: "The imaginary privilege contended for in the ultimatum of the negro convention, at least as affecting the school question, is not attainable. Furthermore, it is calculated to deprive them of the education privileges they at present enjoy."

The Union American criticized the Knoxville Chronicle and the Chattanooga Commercial for "Having nothing to say on this very life issue sprung upon us by the blacks themselves. They have the ear of the negro, which we have not, and their words of advice have an influence with the race that Democratic organs cannot pretend to."

The May 8, 1874, P&H noted that of 88,500 Republicans in the state, 40,000 were Black. "Without their votes the Republican Party could not elect a single congressman in any district. The colored voters form an important element in the Republican vote of Tennessee."

With the school desegregation clause removed, the Civil Rights Act passed in the U.S. House of Representatives Feb. 5, 1875, with 162 yeas and 100 nays. It later passed the U.S. Senate and was signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1875. It gave Black citizens the right to be accommodated in inns, public conveyances, theatres, restaurants, hotels and places of amusement.

Twenty-two days later, the Tennessee legislature passed a law that nullified the newly passed Civil Rights Act. It began another 89-year struggle.

Robert J. Booker is a freelance writer and former executive director of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center. He may be reached at 865-546-1576.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Black Knoxville men worked hard for Civil Rights Act of 1875 | Opinion