Black and Latino Austinites are moving farther east. City says affordability is key issue.

It is early in the process, but newly married Christino Herrera, a 28-year-old H-E-B manager, is doubtful he’ll be able to buy a home in Montopolis — the neighborhood of his family and his youth.

Herrera’s family has lived in Montopolis since his grandmother bought a house there in the late 1980s after living in the nearby Holly neighborhood, just north of Lady Bird Lake. Herrera lived there until he was 21. His grandmother and mother have not left. But with Montopolis prices outside of his and his wife’s budget, exterior communities such as Buda and Del Valle appear more likely options for the couple set on buying a home. At least for now.

Coming to terms with this reality was “hard,” Herrera said. “I thought I’d live in Austin my entire life.”

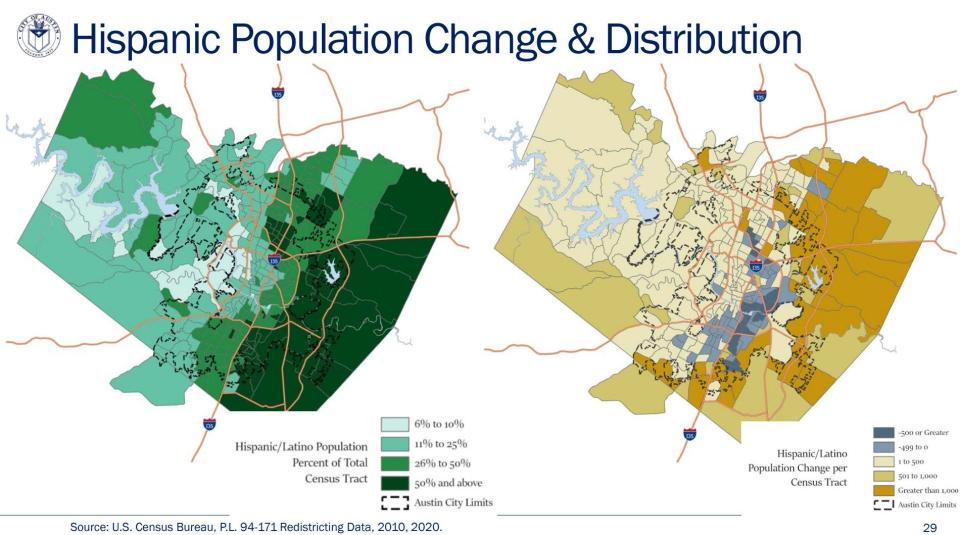

If Herrera moves to a community such as Buda or Del Valle, he would join the increasing trend of outward Latino population growth.

Austin's Eastern Crescent, its belt of traditionally economically disadvantaged and often nonwhite neighborhoods, continues to move farther east in Travis County, according to the city.

A Dec. 12 report from city demographer Lila Valencia shows that while Austin ranks highest in many quality-of-life metrics among Texas’ metro areas, these advantages have not been equally experienced by all.

The numbers indicate continued disparities along racial and ethnic lines, with Black and Latino residents often lagging behind others. Lower rates of educational attainment correlated to lower household incomes and rates of homeownership, Valencia told the City Council during a work session.

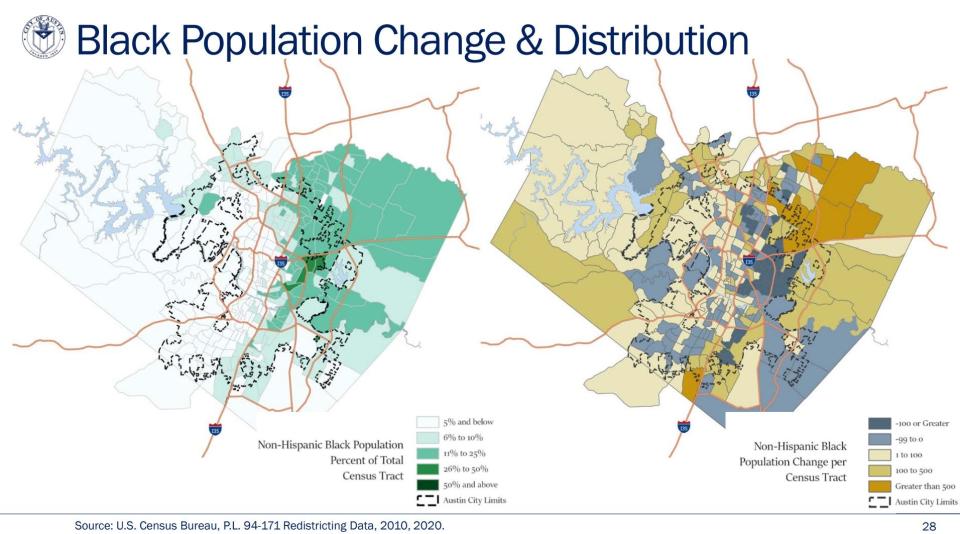

At the same time, the city's historically Black and Latino neighborhoods have lost large numbers of their populations, which are now found farther east, north and south than before.

“Our city is growing, but we are seeing a farther eastward movement of the Eastern Crescent, which indicates that many families, mostly of color, are moving farther away from our city’s resources," Valencia said.

More: Charting Austin’s changing neighborhoods

The continued move east

Valencia's report reinforced past data showing the shift of the city’s Black and Latino communities from east-central neighborhoods, often called the city's Eastern Crescent.

As a trend, large numbers of the region’s Black population moved farther northeast and Latino communities were increasingly concentrated on the city’s eastern fringes.

Council members call for land banking

After Valencia's presentation, both District 1 Council Member Natasha Harper-Madison and District 2 Council Member Vanessa Fuentes called for the city to land bank aggressively along the Eastern Crescent. Land banking refers to the accumulation of property for future projects.

Fuentes and Harper-Madison's districts encompass large portions of the city's Eastern Crescent. Both council members spoke with the American-Statesman about what actions they think could address the issue of displacement.

Harper-Madison said she believes Austin has an obligation to land bank in the far eastern parts of the city — such as east of U.S. 183 — where it expects to see continued development. She hopes properties purchased now can be used later for community land trusts, associations that hold land collectively and sell houses on it, lowering homeownership costs for their communities.

“It’s ripe with opportunity,” Harper-Madison said of the area east of U.S. 183. “And if we … don't do something to sort of fragment some of that off and store it away, then it'll be gone just like everything in (central East Austin) is gone.“

Fuentes shared similar sentiments about land banking, adding that several parcels in her district were purchased by the city using housing bond dollars.

"We just now selected the affordable housing developer to move forward on actually producing the homes, and we'll have the largest community land trust on one of those parcels," Fuentes said.

One development will have several single-family homes across from Mendez Middle School, Fuentes said. Another parcel nearby will have affordable apartments.

"Both of these developments will have our preference policy tied to it," Fuentes said. "What that means is that we are going to prioritize individuals who have generational ties to the area, who have been displaced and who live in the area."

Going forward, Fuentes would like to see the city buy land in the Del Valle area.

Both Fuentes and Harper-Madison said fighting displacement will require continued investments to stabilize communities.

Though the central point of this is housing, it also requires city investment in child care, education, recreational spaces and health care. Its about "breaking cyclical poverty" and giving residents agency, Harper-Madison said.

How do the numbers stack up?

According to the report, Austin’s Black and Latino residents are less likely than non-Hispanic white residents to have a bachelor’s degree (43.6% and 32.5%, respectively, compared with 60.3%).

According to Valencia, the high correlation between education and income begins to explain the other gaps.

Incomes have grown across the board, but the “different starting points” mean that divides remain as they have.

The average Black household earned $75,103 and the average Latino household made $77,461 in 2022. In comparison, the average white household made $103,003 and the average Asian household made $129,551.

The disparity in income, alongside the city’s long-expanding housing costs, have repressed homeownership for Black and Latino residents, Valencia said.

At $460,000, Austin had the highest median home price of any Texas metro area in 2023 — $60,000 higher than second-place Dallas, according to Valencia's report. As a whole, Austin’s homeownerships rates are the lowest among Texas cities, and Latino and Black residents fare particularly poorly.

About 53% of Latino and 40% of Black households are homeowners, per the city’s report. That’s compared with about 59% of all Austinites. It’s the lowest rate for Latinos in the state and just above Dallas-Fort Worth and El Paso for Black residents.

Rental prices are up too, rising 39% after inflation over the past 10 years, and the city's share of renters is at its highest since 1990 at 58%.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Austin's Black and Latino residents are moving farther east, city says