'Black Medicine for a White Boy.' Pastor's memoir remembers Canton's Dr. J.B. Walker

CANTON − In 1954, the idea of a white family having a Black doctor was practically unthinkable.

It some circles, it probably still is.

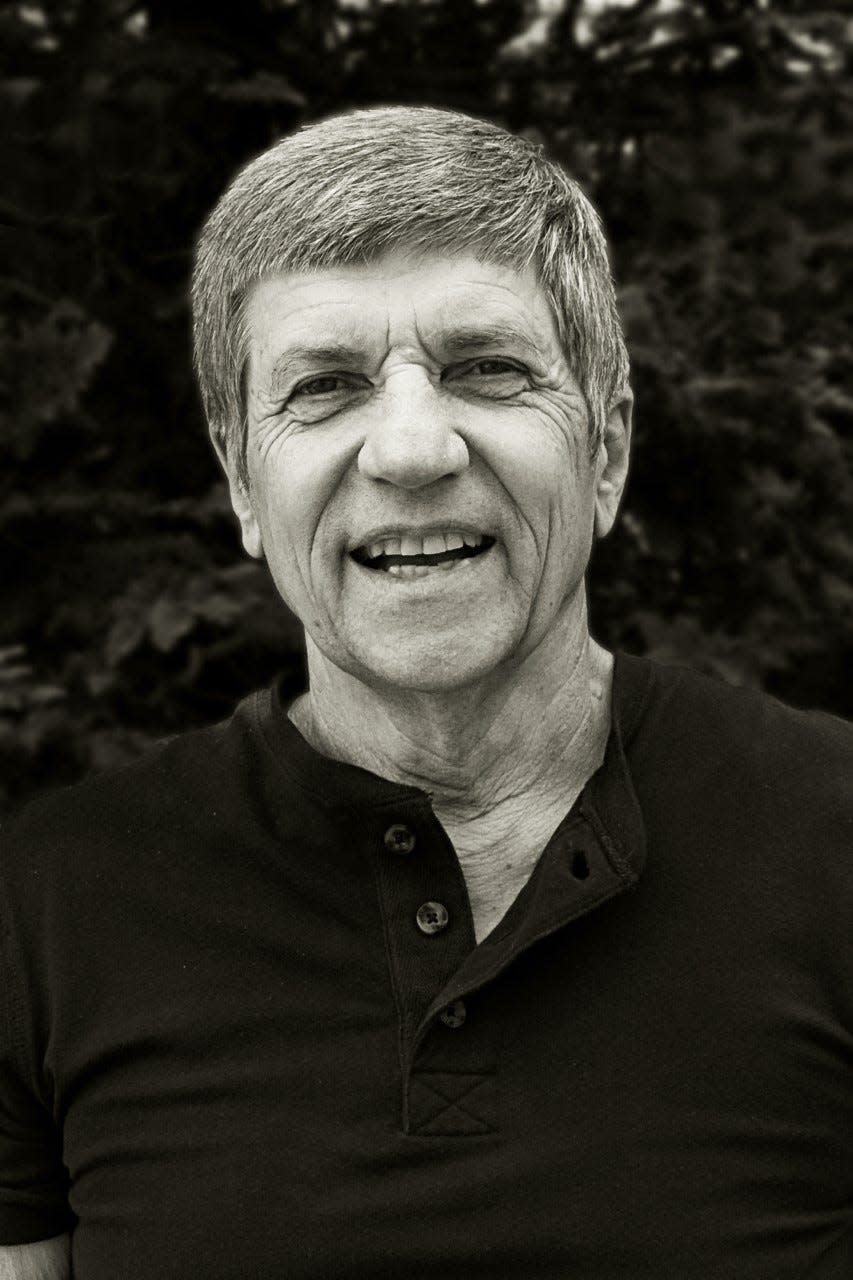

The Rev. Rich Hites has captured his family's extraordinary experience as patients of Dr. J.B. Walker, the city's first Black physician, in his new memoir, "Black Medicine For a White Boy."

A retired Lutheran pastor who lives in Hickory, North Carolina, the 73-year-old Hites was a child in 1950s Canton when it was a bustling city of more than 100,000 enjoying a post-war manufacturing boom — but decidedly separate.

NAACP news:'It's not a Black organization.' Stark NAACP seeks to return to its diverse roots

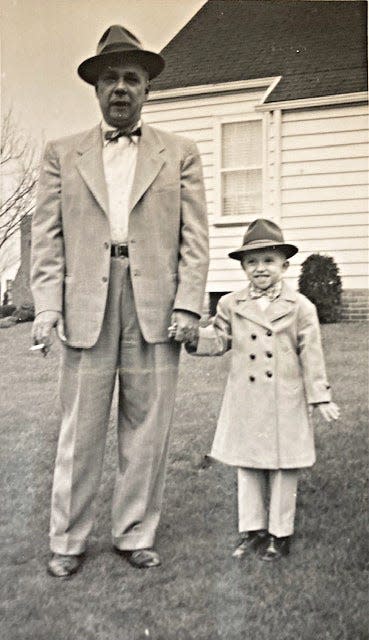

The Hiteses were the quintessential 1950s family. His parents were solid conservatives who "liked Ike." The family of four lived in a Cape Cod-style bungalow at 3522 12th St. SW.

Hites' father, Robert, was a chemist at the Timken Roller Bearing Co., where he worked for 45 years. Mom Marie was a homemaker. Hites and his older sister, Roberta, nicknamed "Robin," attended Baxter School.

"There were no Black families on our street; I remember it looked like Levittown," Hites recalled, describing a planned, post-war community in Pennsylvania where racial covenants were embedded in each deed.

Though they lived just a few miles west of the yellow-brick building at 429 Sixth St. SE, where Walker housed his practice, the two neighborhoods might as well have been on separate planets.

But a young Hites soon found himself crossing that divide when his parents chose Walker as their family physician.

Rich Hites: 'They always say write what you know.'

A 1967 alumnus of Lincoln High School, Hites graduated from Malone College and Trinity Lutheran Seminary in Columbus. After retiring as a pastor in 2014, he said he felt called to do something other than supply ministry. He took a writing seminar, resulting in three fiction books.

He employed some of those skills to recreate scenes based on Walker's actual life.

"They always say write what you know. I wrote some fictional stories, and decided to write about my own life experiences," he said. "I thought about Dr. Walker. That was an amazing time; I just plowed in. The pandemic was still on, and I thought, 'I'll see how much I can find.' It was difficult. I also wanted to capture some the larger issues, like the civil rights."

Dr. John Benjamin arrives in Canton

When Dr. John Benjamin Walker and his wife, Theressa, who went by her middle name, "Etna," arrived in 1920 in Canton from Washington, D.C., the city's Cherry Avenue SE neighborhood was becoming the pulse of Black life, an effect of "The Great Migration," when millions of Black Americans began fleeing the Jim Crow South.

Memories of "Cherry Avenue:"Golden age of Black business in Canton

However, because segregation existed in the North, too — it just wasn't as overt or codified — Cherry Avenue became a social necessity and a mecca for Black-owned businesses. Most Black newcomers were relegated to housing in southeast Canton, joining Italian immigrants.

Hites said his parents never explained their reasons for choosing Walker, only saying that he was recommended by their white Catholic neighbors, Jim and Rosemary Schaffner.

"I think they had been going to him a little while," he said. "My dad was a very conservative person, but if you had to catalog him today, he'd be a liberal Republican. He had a real leaning toward the truth. He also, in the midst of that, had a sense of injustice. They wouldn't have called it that in the 1950s, so much, but he had a real sense of it; of treating people fairly. That all just flowed in to it."

Hites said his mother especially liked Walker's nurse, the late Willa Mae Hart.

"I don't recall anyone saying 'Why did you go to him?'" he said. "They had some fairly conservative friends from work, but I don't remember any pushback. That was the strangest thing, considering that era. I also don't remember any from my grandparents, on either side. They were pretty conservative as well."

Hites' book also shares a child's eye view of the nation's struggle over civil rights as it was happening, and how he believes having Walker as a physician might have helped to broaden his parents' perspective.

"They were not always comfortable with the issue, but they were not antagonistic," he said. "I think what it did was open their eyes to the injustices that were done. I think it opened them to things happening in Selma. It opened my eyes to see that, too, so that when I went on to seminary and there were courses we took in current church history, and they involved civil rights, I felt I could more openly discuss those issues in my classes."

Who was John Benjamin Walker?

Born in 1889 in Avalon, Virginia, Walker was one of 13 siblings raised on a 40-acre farm founded by his formerly enslaved grandfather Monroe Walker. When Walker was 10, he witnessed his best friend, Stephen Griffiths, being lynched when he was accused of stealing.

Walker attended the Howland School, founded by Emily Howland, a white Quaker on a mission to educate Black children. After acquiring an academic degree in 1912 from a school in Heathsville, Virginia, Walker entered college and medical school at Howard University in Washington, D.C, where he met his future wife, Theressa "Etna" Nutt, who was studying to be a teacher. He completed his internship at the city's Freedman's Hospital.

But medical school was interrupted by World War I. According to Hites' research, Walker was not deployed as a medic. Like many Black troops, he was instead assigned to serve under the French as a Services of Supply laborer to dig trenches and offload supplies.

"For all the furor these days around the National Archives, I got hardly anything out of it," he said with a laugh. "There are horrible military records. They are sketchy because a fire in 1973 destroyed the Army's records. It was hard to get anything, especially in midst of the pandemic."

A community-minded couple

Hites said he was aided in his yearlong research by Stephanie Houck at the Stark Library's Genealogy Department and by the North Cumberland County Historical Society in Heathsville.

Notables in local Black historyBlack history is bolstered by the accomplishments of many from Stark County

Assisting Hites in the editing process was Geraldine "Gerry" Radcliffe, a retired nurse-turned-community historian. She's is a contributor to the 2019 book, "African Americans in Canton, Ohio: Treasures of Black History," which includes a segment on the Walkers.

A native of Massillon, Radcliffe said she didn't know Walker personally but reached out to the son of the late Dr. William Gregory, who was a child when his father and Walker were partners.

"He was 4 years old at the time, and remembers (Walker) coming to the house, but didn't know too much about him," she said. "I contacted the Stark County Medical Society and Aultman and Mercy, where he was on staff. The Stark County Medical Society couldn't find anything in their records, and Aultman wouldn't allow me to access their records."

After World War I ended, Walker completed medical school in 1919 and the couple married, shortly after which they moved to Canton.

"He didn't mention why he chose Canton," Hites said as he recalled their conversations during his office visits. "I think it was such a bustling time, and during the Great Migration, and he was part of that movement. I just kind of pieced together that when they moved, it was so close to the Tulsa Massacre."

"I wonder if they didn't sense a tenuous state of affairs, even in Washington, D.C. I think they kind of liked the smaller town, but in fact (Canton) was a bustling city at the time. How he discovered it, I just can't tell you. I think he researched it out. She didn't have any reservations, as far as I can tell, which is surprising because her family was well established in Washington, D.C."

The newlyweds jumped right into leadership in their adopted community. Walker was a founding father of the Canton Urban League, which recently celebrated its 100th anniversary, and a co-founder of the BB's, or Bon Bon Buddies, a Black businessmen's social club.

Etna Walker served as vice president of the Urban League, was a member of the executive committee of the Ohio NAACP, and executive director of the Phillis Wheatley Association, which provided housing and job assistance to young Black women arriving in Canton because they could not rent rooms at the YWCA or in hotels.

Today, the former Wheatley House, which still stands at 612 Market Ave. S, is occupied by a private business. She also started the American Workshop for the Blind, and served on a number of local civic boards, including the Red Cross, Aultman and Mercy hospitals, and the Ohio State Women's Committee for Health, Education and Welfare.

'Before Oprah and Michelle Obama, there was a Theressa Nutt.'

The couple attracted influential friends and allies. Among them was the Rev. Ernest J. Newborn, a civil rights leader and pastor of the Cherry Avenue Christian Church, where they attended services, and Euell Edwards, chief loan officer at the First National Bank, which gave Walker the $9,000 mortgage for a home at 825 Broad Ave. NW, which was unprecedented in the 1920s.

"I think it was amazing that the First National Bank was so amenable in granting him a loan," Hites said.

The friendship and support of educator and civic leader Barbara Schreiber led to Etna Walker becoming the first Black Junior League Woman of the Year in 1954.

"Before Oprah Winfrey and Michelle Obama, there was a Theressa Nutt," Hites said. "She was a dynamo who did some amazing things."

According to "African Americans of Canton Ohio," the Walkers' arrival paved the way for more early Black medical professionals in Canton, including his first nurse, Myrlene Henderson; Drs. Mantel B. Williams, S.W. Gregory, P.M. Ross, A.B. Royal and Gwendolyn Ford; dentists P.M. Richardson, Guy Taylor and William Wilson; pharmacists Joe Brewer, Merion Cosey, Clayton Umbles, James Thigpen and Fred Johnson; pioneering nurses Bernice Iman and Margaret Warren; and anatomic artist Norman Hall.

Significant contributors:These Black women have made history in Canton

Two wishes for readers

Hites noted that while the couple was engaged in public service, they were private when it came to their family life.

He recalls seeing a photo on Walker's desk of their only son, John, in his World War II uniform. John, who later moved to the Springfield area, is deceased. Their only daughter, Theresa G. Walker, moved to New York City, but Hites said no further information about her could be found.

"I couldn't find any grandkids or anyone who remembered them," he said.

Hites said he visited the Walkers' old house in 2017, when he returned to town for his 50-year high school reunion. It's a stone's throw from his family's old church, the former Bethel Lutheran, at 701 Broad Ave. NW. Today, it's occupied by a nondenominational church.

"It still has the sun porch, which was his home office area," he said. "He kept weekend hours and had no hesitation about making house calls, but I think he did it with a little bit of fear and trembling because he didn't know how it would be taken in a white neighborhood. That was not an easy thing for him to do."

One of those house calls was to 3522 12th St. SW when Hites fell ill with a serious form of measles in 1958. He writes that as soon as Walker left their house, their phone lit up with calls from curious neighbors.

The book also details an incident in which Walker was once shot at three times by an unknown person while getting into his car outside of his office. He was not injured.

After Etna Walker died in 1957, Walker continued in his practice, eventually marrying his brother's widow, Hauzie, a decision which Hites said engendered some controversy at his church.

Walker died at 76 on May 11, 1965. He was buried in Forest Hill Cemetery alongside both wives.

Hites said he has two main hopes for people who read the book.

"No. 1, we are part of history and a flow of historical events even if we don't directly touch them," he said. "The Tulsa race riots and marches of Dr. King were flowing around us like a river. We were part of it, even if we didn't realize it.

"The other thing I would hope to portray is that crossing racial lines is important in every day life. I think we must break down any barriers we have and accept one another as human beings, as individuals, and seeing the worth of every person. "

Copies of "Black Medicine for a White Boy" are available at the Stark County District Library, the William McKinley Presidential Library & Museum, and amazon.com. Copies also will be available at the local author's fair on March 4 at the Stark Library at Radcliffe's author's table, and at the Massillon Public Library's Authors' Fair on March 18.

Reach Charita at 330-580-8313 or charita.goshay@cantonrep.com. On Twitter: @cgoshayREP.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: "Black Medicine for a White Boy" honors Dr. J.B. Walker