Black men targeted by police, citizens in a panicked Virginia town as intruder assaults fifth woman

Kalorama Street hugs the side of one of the many hills in Staunton. The stocking mask rapist of 1979 would get there by walking a minute up a side street, past the Stonewall Jackson Hotel and its giant neon sign which could be read literally a mile away by drivers coming off the highway into town.

After the large hotel building, the side street abruptly ends and the path plummets down 30 feet below; turning along the side of the hill, the stocking mask rapist would be on Kalorama.

The street, even in 2022, is almost pitch black at night.

The streetlights may be the same that the stocking mask rapist walked beneath as he found his way to the ornate stone house that October night, stepped up into the tangle of bushes and the winding stone stairway, and disappeared from sight.

She’d fallen asleep while reading, the light in her room still on, when a sound outside awoke her. She looked out the window and saw nothing.

She dozed off again for a few minutes, and then he was in the room, on her, straddling her.

The details of what happened next on Oct. 2, 1979, are not clear from the police incident report, which is disjointed and riddled with spelling errors and strange statements like “Subject walked with a lope that indicated he was young.”

His voice is described as both rough and smooth. The report doesn’t state whether the rapist was lying in wait or broke into the building while the victim was home. It’s not clear whether she was assaulted once or twice.

What’s known from the police report that ties it to previous attacks is that the rapist held a knife to the victim; that he apologized to her several times, once after grazing her back with his knife as she turned over to try to talk to him; that he told her that his girlfriend had been “kilt” in a car wreck a year earlier. Like the rapist who struck on Vine Street, he asked the woman if he could visit her at her home in a few days, an odd request which the police had already taken seriously once, to no avail.

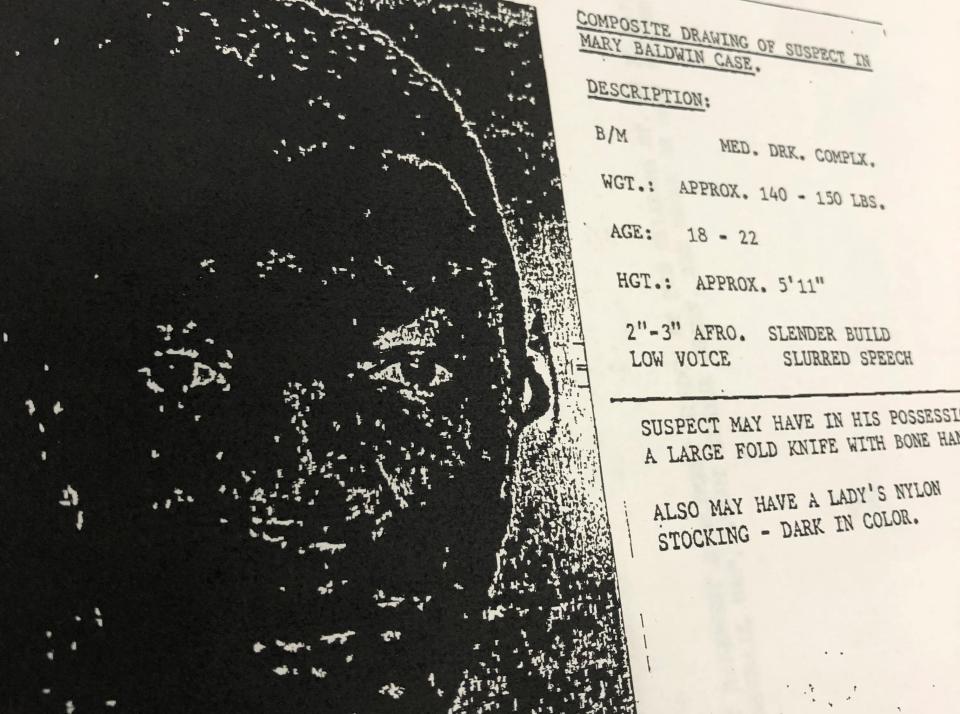

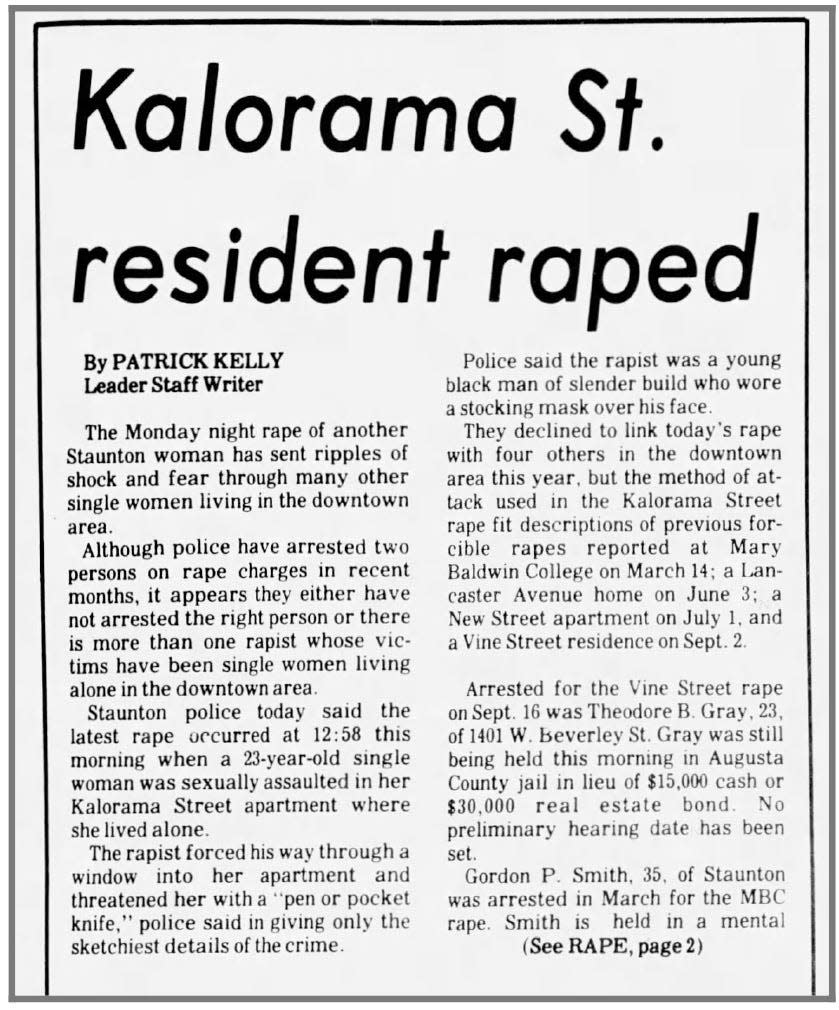

What was known is that it was at least the fifth rape that year by the same unknown subject, a Black male with a stocking mask and a knife, and his second attack in the last four weeks.

Things weren’t getting better, despite the news of the arrest. They were getting worse.

*

North of City Hall lay a few blocks that in the late 1960s and early 1970s looked like Skylab actually had crashed there. They were the remains of a swath of several blocks, including the city's Black business district, that had been destroyed, building by building, by federally funded urban renewal.

Ostensibly, the teardowns were to make room for a mall or shopping center. The replacement was never planned and never built. In its place came a handful of modern bank buildings and the long macadam skirts of their mostly empty parking lots.

The mall was eventually built elsewhere, but one thing was achieved, planned or not: the elimination of Black businesses from this small downtown by white-dominated government power structures.

One young Black girl who grew up in the area revisited the site of her childhood decades while participating in a march in Staunton in the late spring of 2020 after George Floyd was killed. She told a News Leader reporter how the march, which took the crowd south down Central Avenue, gave her the chance to walk with her daughter into the part of town she remembered from her own childhood. A place now invisible to all.

Others who grew up here remember it well, too.

“I can close my eyes now, and walk down Central Avenue, and remember what it was like,” Brenda Canning, who grew up just a few blocks north of Central Avenue, said from her porch in June 2021. “There was the bus station, an ice plant. A skating rink. There was a Packard dealership. There was a coat factory, a hosiery factory. It was just amazing.” Many of the businesses were white-owned, as well. Canning remembered the area as lively and full of people, businesses and their customers and residents of the district sharing the space in “beautiful old brick buildings.

“And then we just razed them.”

Those buildings — 32 in all — contained 26 businesses and 17 households.

After it was all gone, “most of the cleared land remained a weed-infested vacant lot for about 10 years,” according to “Staunton Virginia: A Pictorial History."

Disdain for and destruction of Black spaces in Staunton was the backdrop still, as the 1970s came to a close. It was the context for the cityscape where the stocking mask rapist tragedy would play out.

And as newly empowered voices of women, mostly white, demanded protection and justice — the police turned their attention to the segment of the population they were used to ignoring most of the time and then dealing harshly with when a problem arose: Black men.

“Back in 1979-1980, I guess the black-white thing was even a little scarier than now,” said former commonwealth’s attorney Ray Robertson, casting his mind back in the past to talk about the case.

The panic that gripped the town was real. “It was just an unsettling feeling, just not really knowing. And I guess we’d always been so comfortable,” Canning said.

White people had been comfortable, at least.

“1979 was no different than any other year for the last 400 years on this continent,” said Staunton native and Black resident Jerry Venable. “Black men have always had a target on their backs.”

Venable may not have been a target of police. His height was closer to seven feet than six, and much of the year he was touring as a member of the Harlem Globetrotters. But his friends felt the heat, and by the fall you couldn’t walk down the street of your hometown alone without a cop nipping at your heels asking what you were doing out.

“That year,” Venable said, “the circumstances just exposed things for what they were.”

In late September, the commonwealth’s attorney understood two other things that had been exposed for what they were, even before the stocking mask rapist attacked a woman on Kalorama Street. He had already been part of the city arresting and incarcerating two Black men wrongly.

“Smith didn’t commit the Mary Baldwin rape. Gray didn’t commit the Vine Street rape.”

He would have an uphill battle to exonerate Teddy Gray. He’d been identified by the victim of the September rape from a photo lineup, “and she also identified him by voice.” Worse, Gray had flunked a polygraph.

The other uphill battle was for the police to fight. They’d dug themselves a deep hole. As news reporter Roland Lazenby said, “The department was more interested in arresting the guys than in warning the public.”

Now, after police had arrested two Black men identified on the street by white women, the real predator had broken into another house and raped again.

They needed to find the real stocking mask rapist.

They made the decision to call in psychic Noreen Renier to visit Staunton.

With scant physical evidence and two incorrect eyewitness identifications by white women against Black men, what help did they expect from a psychic?

“I’ll tell you what,” Robertson said. “They were looking for anything they could get.”

*

Noreen Renier’s typical clientele for her psychic services were usually inebriated, always curious and sometimes desperate.

Her new client, the Staunton Police Department, was definitely desperate. Other than that, “typical” didn’t describe what the nightclub psychic and part-time adjunct teacher was about to get herself into in the fall of 1979.

On a normal job, she would set up a small table in a hotel bar, prop a posterboard nearby with her photo and the words “NOREEN Psychic in Psychometry” advertising her services, which included “revealing personal insights,” and her terms — “Five dollar gratuity customary.”

She’d buy a glass of wine at the bar, survey the room, maybe make some small talk, then sit down at her table. She favored fashionably flowing dresses complementing her equally flowing dark hair, well aware that even in her early forties she commanded a type of attention that had nothing to do with mind-reading, though that might have been easy enough to do, too. She’d sit at her table and mind her drink as she waited for her first customer.

Eventually he’d wander her way, because most often it was a man, swerving to stop at the bar or pausing by a table so he’d not seem so anxious to get there.

The customer would hand her a personal object: a watch, a necklace, a ring.

And Noreen Renier would hold it, sit for a moment with it, then start talking.

She’d describe images, feelings, even smells, as they came to her. She could tell if the person had been upset about something; if he had scars or tattoos on his body; if an old injury was nagging him or an old love was haunting him.

The interaction would often land her a tip in addition to the half-a-sawbuck standard, and sometimes another drink.

On occasion she would fall into a semi-trance while practicing psychometry. She often felt things as if she was the person involved; more like first-person recollections than investigative findings.

This included the bad experiences. “The worst was burning,” she remembered in a 2019 interview. Holding an object hundreds of miles from a crime scene, she’d described in detail how many times a child had been stabbed after she was found hiding in a closet, and then talked about how the killer paused in the bathroom, mesmerized by the sight of blood running down his hands as he washed them in the sink.

Metal things, rings and knives, seemed to store vivid images and sensations. Even clothing, like a shirt or dress worn by a murder victim, held memories.

The intensity could be overwhelming. In the years to come when she’d visit crime scenes with police, she would be so exhausted after those trance-like hours and wired at the same time that she’d have to retreat to her hotel room, drink a glass of wine and fall asleep for hours in the middle of the day.

Some detectives she worked with knew her so well that she’d come back to her hotel room and find a chilled bottle waiting for her by the door. After hours in a dreamless sleep, she’d wake in a pitch-dark room, hungry and disoriented but finally rid of the residue of the experience.

And that would be that. She wasn’t “on” 24/7 like many people believed about psychics.

She couldn’t walk down the street and effortlessly read people’s minds and see their auras blooming from their heads like psychedelic flowers. Most of the time she didn’t feel like a famous psychic who could find things no one else could. She could barely follow a road map to find her way to her next job.

She could go for days without thinking a psychic thought, and often preferred that, especially after a job. “When I’m not being psychic I don’t know anything,” she said. “I get lost in Kmart.”

Hardly the traditional psychic according to mainstream terms, and hardly the traditional tool for law enforcement. Then again, traditional detective work had not been paying off for the Staunton Police Department.

Traditional detective work had left the force with five rape victims, and two Black men sitting in jail while the rapes continued. It had led to accusations of withholding information from the public and lying to a newspaper reporter.

Traditional detective work had led the police to admit that waiting four days to issue a press release about the Oct. 2 rape had gotten them no further in pursuing investigative leads.

By mid-October the reward for identifying the stocking mask rapist had risen to more than $1,000.

Police Chief J.M. Boyers and Capt. D.L. Bocock, head of the investigative division, were under scrutiny from the mayor’s office.

Neither were known for their sensitivity.

Boyers had told the paper flatly in mid-October when reporting no new leads or suspects: “People are going to have to learn to protect themselves a little.”

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a storytelling and watchdog coach in USA TODAY Network. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

NEXT UP IN ‘THE STOCKING MASK’

Capt. Bocock spent most of October defending himself and his force against accusations of lying. “We have not told the press lies. I have not told the press lies. The people don’t know the facts of what has been done and what is being done. They don’t realize how hard it is to catch a loner,” Bocock told the press.

But he didn’t seem to want any help; earlier, Bocock had warned that it might be dangerous if women decided to arm themselves with guns and patrol the streets like vigilantes. Things in Staunton were almost getting to that point.

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Staunton VA police target Black men in 1979 Stocking Mask Rapist case