This Black Mom Invented Skin Tone Emojis, But Her Patent Attempts Have Been Shot Down Repeatedly

Katrina Parrott

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 2013, Katrina Parrott came up with the idea of emojis in diverse skin tones, years before they made their way to smartphones around the world. Ten years later, the Black mom from League City, Texas, said she is still waiting for recognition for her idea — and a patent, for which she has been rejected multiple times.

“It’s really frustrating,” Parrott told BuzzFeed News in an interview, “when you put your heart and soul and resources into an idea that has impacted so many lives, and then be rejected when you go to the place to formally get recognized for it.”

This week, lawmakers are using Parrott’s example to demand answers from the US Patent and Trademarks Office about why people of color, women, and other underrepresented inventors are granted significantly fewer patents than Big Tech. On Monday, Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas sent a letter to the USPTO demanding answers to a dozen questions around the subject by Feb. 28. The letter came about after Parrott approached Warren for help.

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (left) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren

“We are writing to express our concerns regarding the disproportionate challenges that small businesses, women, people of color, and other underrepresented minorities face in the patent approval process,” the lawmakers wrote in the letter, a copy of which was reviewed by BuzzFeed News.

They pointed out that Parrott has received multiple patent rejections for her diverse emojis over five years, while Apple, whom Parrott unsuccessfully sued for copyright infringement, was granted more than 2,500 patents in 2021 alone.

“When giant tech companies like Apple are granted patent after patent by the USPTO, women and entrepreneurs of color face steep hurdles in getting credit for their ideas — and too often see their patents rejected,” Warren said in a statement provided to BuzzFeed News. “The USPTO needs to do a full accounting of how and why entrepreneurs of color disproportionately have their patents rejected and level the playing field for small business owners taking on Big Tech.”In a response to a BuzzFeed News inquiry, a USPTO spokesperson said that the office “is well aware that both in the US and in our allied countries, the rate of participation in the innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem, including in patenting, is not representative of our communities at large.” They added, “The USPTO has undertaken extensive and concerted efforts during the Biden Administration to ensure diversity, equity, and inclusion throughout the US patent system, as well as to identify any reasons those who apply for patents are not awarded them.”“I feel as if I’ve been harmed,” Parrott said. “And I just want my patents at this point.”

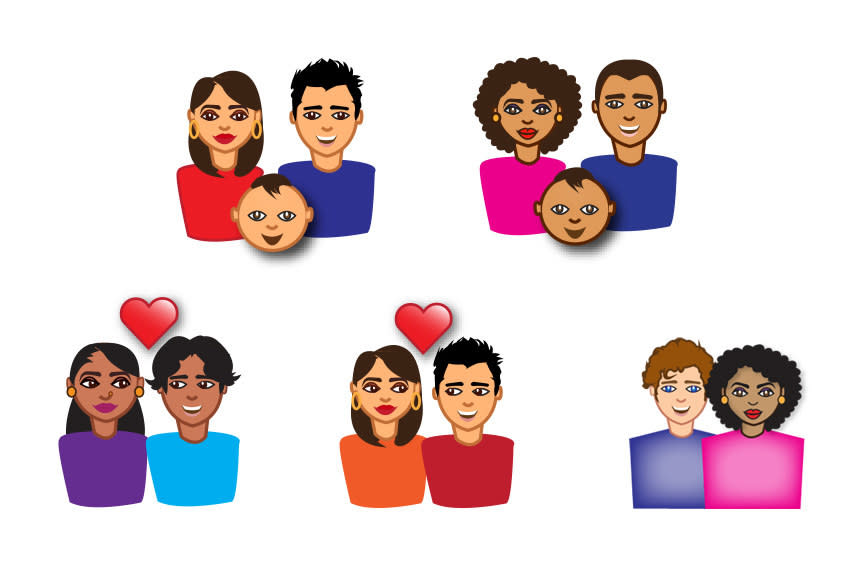

Diverse emojis designed by Parrott

Parrott is 64 and has worked in the aerospace industry for more than two decades. One weekend in 2013, her daughter, Katy, came home from school and lamented that she couldn’t send an emoji that looked like her to her friends. “My first question was: ‘What’s an emoji?’” Parrott recalled.When she researched, she realized that there was an easy solution — creating emojis that didn’t all look alike but came in five distinct skin tones. She hired a software engineer, an illustrator, a copyright specialist, and a videographer, using more than $200,000 of her savings, and ultimately launched an app called iDiversicons in Apple’s App Store later that year. For 99 cents a pop, people could get more than 300 diverse emojis, which they would need to copy and paste into messages since Apple didn’t allow other companies to manipulate the iPhone’s keyboard at the time.

In 2014, she was invited to present at the Unicode Consortium, a Silicon Valley nonprofit in charge of standardizing emojis so that they can be sent across devices and operating systems. The consortium counts large tech companies like Apple and Google among its members. “All of these giants were coming up to me at Unicode and telling me how nobody took emoji diversity seriously until I came along,” Parrott said.

That presentation led to a meeting with Apple executives at the company’s Cupertino, California, headquarters. They reportedly were impressed. Parrott said she left the meeting hoping to strike a partnership with the tech giant to incorporate her diverse emojis into the iPhone’s keyboard.

Diverse emojis designed by Parrott

Later that year, the members of the Unicode Consortium agreed to include five different skin tones as a standard of emoji thanks to Parrott’s push, according to a Washington Post report. But a few weeks later, Apple declined to work with Parrott on diverse emoji, saying that the company would design its own based on Unicode standards and build them directly into the iPhone’s keyboard. The move made iDiversicons redundant.

“I thought I was doing everything right,” Parrott said. “It was tremendously disappointing.”

Parrott then spent more than five years trying to get a patent for her creation, but the USPTO kept rejecting her applications and subsequent appeals. In 2020, she filed a lawsuit against Apple for copyright infringement. Apple’s lawyers reportedly argued that “copyright does not protect the idea of applying five different skin tones to emoji because ideas are not copyrightable.” Last year, a US district judge threw out her suit, declaring that her idea of diverse emojis was “unprotectable.”

“It appeared to me that the judge had already made up his mind, even before we had an opportunity to share anything,” Parrott said.

A disproportionate number of new patents in the US go to rich corporations over small, independent business owners, especially those run by women and people of color. According to one study, over 50% of new US patents went to the top 1% wealthiest patentees in 2020. And another survey, from 2010, found that from 1970 to 2006, Black American inventors received just six patents per million people, compared with 235 patents per million for all American inventors. A 2016 study also found that Black Americans applied for patents at nearly half the rate of whites.

In 2019, the USPTO released a report called SUCCESS (which stands for the Study of Underrepresented Classes Chasing Engineering and Science Success) that it was required to produce under a new law passed in 2018. The report identified publicly available data on the number of patents that women, people of color, and veterans successfully applied for each year. The report concluded that such data was “limited.” Only 12% of US inventors granted patents in 2016 were women, it said, and there was virtually no data available on other groups. “We clearly want this office and the administration to determine what actions has the USPTO taken to improve the collection of demographic data from patent applicants," Lee said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. "The patent office is not an office for Big Tech, or big corporations. The goal of the patent office, from its early historic beginnings, was to drive the innovation and genius of individual Americans."

The USPTO spokesperson pointed BuzzFeed News to initiatives that the agency had put in place to “get more aspiring inventors and entrepreneurs, including from underrepresented communities, involved in the innovation ecosystem,” such as the Council for Inclusive Innovation, the Women’s Entrepreneurship Initiative, and pro bono programs and free services to assist under-resourced inventors.

Jessica Morel, chief marketing officer at LexisNexis Intellectual Property Solutions, described the patent situation as “David versus Goliath.” She said, “It is undoubtedly challenging for individual inventors of all races, genders, and ethnicities, and often smaller companies, to get their patents approved, especially compared to enterprises with specialized expertise, such as patent attorneys, dedicated software platforms, and a track record of successful patent filings.”

Still, other experts argued that Parrott’s original idea for diverse emojis was never patentable to begin with.

“Abstract concepts like different skin color emoji are not something that’s usually patentable,” Ryan Schneer, founder and CEO of Schneer IP Law, a New York–based intellectual property law firm, and a former patent examiner at the USPTO, told BuzzFeed News. “If Apple or Google’s lawyers tried to file the same thing, it would be rejected too.”

Schneer said that although he agreed with the larger point that the lawmakers were trying to make, he didn’t think that Parrott’s case was “the best example” to choose. “If you focus on the wrong symptoms, we’re not going to be able to solve the problem,” he said.

Instead, Schneer said, it would help to focus on the systemic problems in the tech industry, which files a bulk of the patent applications, and which is largely dominated by white men in the US. “We have to start looking at who’s filing the most patents and what their issues are with gender and equality,” he said. “Until we fix the extreme gender inequality in the engineering companies that are filing the patents, I don’t see that the data is going to change.”The patent office spokesperson said that the body is “in the process of rolling out solutions” and cited the appointments of advisors Colleen Chien, a law professor at Santa Clara University whose work is cited in the letter, and diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility expert Caren Ulrich Stacey. The rep added, “Can more be done? Yes. And we look forward to working across government and with Congress to do so.”

The spokesperson confirmed that the USPTO planned to respond to the letter from Warren and Lee by the Feb. 28 deadline. The rep declined to comment on Parrott’s case specifically.

For her part, Parrott plans to see this through. “They used my resources, and my suggestions, and I got no recognition for any of it,” she said. “We were first on the scene. We’ve done all of the due diligence. We’ve been touching people’s lives all over. People are coming up to me and saying, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you for including everybody.’ So what I want is to be able to have a patent on my wall and say, ‘Katrina, you did a great job!’” ●

I Asked Teenagers, 30-Somethings, And People In Their 50s What These Emojis Mean, And I Got Verrry Different Responses From Each GenerationMolly Capobianco · Nov. 13, 2022

Gen Z'ers Have Completely Different Meanings For These Emojis Than Millennials — Let's See If You Know What They MeanSarah Aspler · Feb. 9, 2022

Friends Are Hilariously Taking The Emoji Challenge In Group Texts And It’s The Purest Form Of Internet We HaveTanya Chen · March 29, 2019