Black Mountain resident completes nearly 2-year canoe trip that started in Marshall

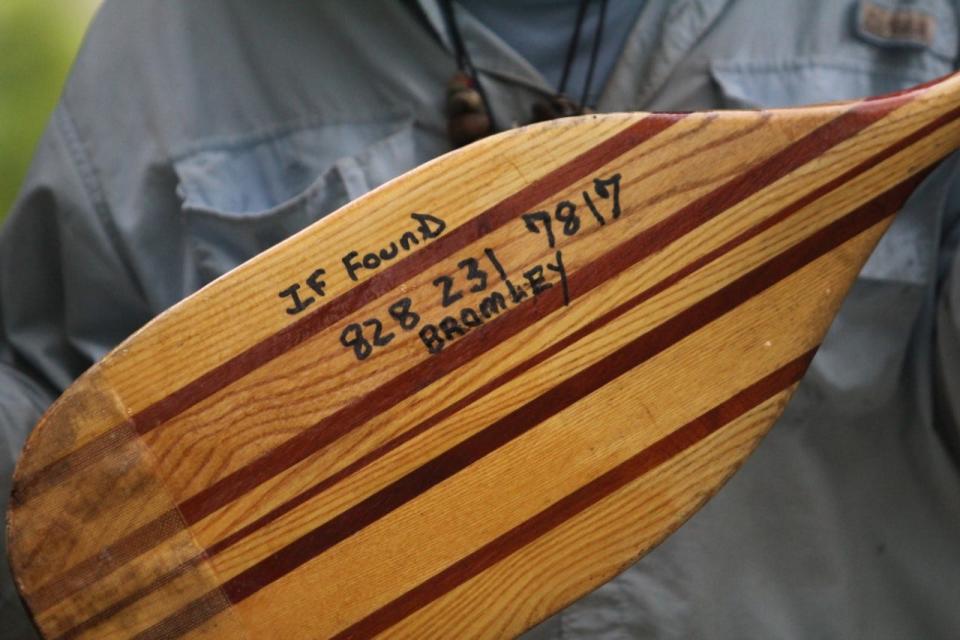

BLACK MOUNTAIN -- "Tow Head" Steve Bromley's canoe trip to Florida started in Marshall in July 2020, and though his goal was to end the trip back in Madison County, he understands better than most that nature will take its course regardless.

Instead, Bromley, a retired merchant mariner from Michigan's Upper Peninsula, stashed his boat in Rosman and went to stay with his sister in Black Mountain, where he then put his boat in storage, officially capping his trip.

"The river gods said, 'We've got a change of plans for you,'" Bromley said of his intention to finish the trip in Marshall. "The river was really booking. There was a multiday delay there. All the banks were overrun. It came up 10 feet in 24 hours. It really flashed. In the meantime, I had bought an airplane ticket to leave (June 4) to go north, where I'm going to be staying for a while. So, you know, I'm comfortable with not making it back to Marshall. I'm all right with it."

Bromley said he chose to start his trip in Marshall after navigating the French Broad from Rosman to Marshall with his son years ago.

News: 13-year-old boy drowns in Broad River; 'rapid, swift water,' say officials

Bromley was given his nickname by a fellow former merchant mariner, Charlie.

"We had both sailed on the same ship, the Medusa Challenger, at different times," Bromley said. "He gave me this huge navigational booklet of the Tennessee River, this huge guide. He told me he had to put me on Facebook. So that got me on Facebook (as Tow Head Steve). Farther down the line, when I was on the Mississippi, I kidded my brother and said, 'If I make it to New Orleans alive, from then on you can call me Tow Head Steve.' Then, it just took off from there."

Bromley's decision to embark on the trip was made easier by the fact that he owns neither a house nor a car, he said.

Originally from the Upper Peninsula in Michigan, Bromley came to live in Black Mountain in 2011 to help care for his sister, who had breast cancer.

"To make a long story short, everything was going good, but I have a problem with alcohol," Bromley said. "I went through this hard time. I started drinking whiskey day and night. I woke up one day and I couldn't walk. I ended up in the hospital for weeks."

After weeks at the hospital, a social worker called the Western Carolina Rescue Ministries, where Bromley lived and worked for a year.

"I got my legs back," he said. "I learned to walk again. It took me a year. They saved my life, and as a result they changed my life."

Shortly after he got out of the WCRM, the coronavirus put his plans for a Canadian paddle trip on the back burner. Instead, he set his sights on a more local trip, shipping out from Marshall.

Bromley has done numerous canoe trips, both in the U.S. and Canada, but had never done a Florida trip.

"I turned to my buddy and said, 'I wonder if you could canoe to Florida from Asheville?'" Bromley said. "I started at the French Broad River and went all the way to the west coast of Florida."

Visiting Our Past: History, geography may define WNC regions better than new boundaries

He said he planned to do the most recent trip in increments.

"The original plan was to meet in Florida, where I had a friend, for spring training, as something to do," Bromley said. "I thought, if I could do the first 200 miles to Memphis, I might have a chance to continue. I didn't know anything about nothing. I didn't know anything about the Tennessee (River). I knew the French Broad had whitewater down below Hot Springs. When you've got 300 pounds of gear, it's a whole other ballgame."

Despite his planning though, Bromley's trip was not always smooth, as he tore ligaments in his knee within the first hour of the trip.

"I couldn't even walk," he said. "I thought the trip was over before it even started. But I didn't let that stop me."

Once it did start though, there was more danger ahead for Bromley.

"I damn near got killed within the first couple of days," he said. "On the second day, I flipped the boat (in Hot Springs). There's a bend on the Mississippi called the New Madrid Bend. You go 10 miles north to go around a 5-mile bend, to go 10 miles south, to get back to the same latitude you started at. On the outside of these big bends are embankments - pure rock. I get along the embankment, and next thing you know I'm screaming, and I'm backpaddling hard, with no eddy to pull in to, nothing.

"All of a sudden, here comes this tug barge about 800 feet long, and he's coming around the corner, and he's doing a maneuver called flanking, where he reverses the engine to swing their barges. That wind got a hold of us and started heading down towards that embankment, and where was I but right in between the embankment and the barge. That guy got within 100 feet of me. I was ready to bail, and I would've really screwed myself up jumping on them rocks."

Last spring, Bromley made his way through Savannah, Georgia, and stopped June 10, 2021, in Carrebelle, Florida, due to the threat of hurricane season. He left his boat on a farm there and flew north temporarily. He returned to Florida Dec. 1, 2021, and restarted his trip. He spent 17 months on the water in total.

He turned back around in St. Mary's, Florida, near Cumberland Island National Seashore Park on the Atlantic Ocean.

"There were days I did not paddle," he said. "I was either too tired or the weather was bad."

Bromley paddled five to six hours a day, he said, including a lot of night paddling, often starting as early as 2 a.m.

His plan of following the bank also went out the window because the Mississippi has 12-feet-high wingdam rocks that jut out from the shore, he said.

Despite finding himself in precarious situations early on in his expedition, Bromley has no regrets about his trip, he said.

"I was shown so much love on this journey from folks that I never knew existed. I never knew where or how I would meet them," he said. "Nothing was planned. I never knew 90% of the time where I was hanging my hat that night."

Bromley said some of his fondest memories of the trip happened around 680 miles in, near Paducah, Kentucky, at a campsite below a Hilton hotel.

In Paducah, Bromley met a former commercial fisherman and dobro player from Ohio named Jack Martin, who played alongside bluegrass icon Lester Flatt.

Bromley even sat in on a practice session of Martin's band, Good Company, at his house before getting back on his canoe.

Answer Man: New bridge for Pratt & Whitney causing 'whitewater' ride? White bus mystery?

According to Bromley, he experienced a number of synchronicities along his trip.

"He had two paintings of a shanty boat and an old Mississippi sidewheel, signed by the artist Harland Hubbard," Bromley said. "It turned out Harland Hubbard and his wife, Anna, built a shanty boat up near Cincinnati and took four years floating down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in the '40s. They would stop over in the winter and glean the fields for food and fish."

Martin even gifted Bromley a copy of Hubbard's book, "Shantyboat," which served as an inspirational guide for Bromley's trip.

"I went through it page by page — where they camped, where they tied their shantyboat up," he said. "While they floated at medium level on the Mississippi, I was at low, though. I stopped in all the towns they stopped in. I searched the hardware stores, the post offices they went to. I followed the narrative as close as I could. It changed the whole trip for me. It made it so much more personal."

After Paducah, though, Bromley's trip became dicey once again, as he navigated the often unpredictable Mississippi River.

"Every body of water is different, and I had to learn the Mississippi," he said. "I didn't know anything about it. If I had known anything about the Mississippi, I would've never done it. And I kind of know what I'm doing. But that river is so big, and it was going on winter. I learned right off the bat that the current that I wanted so much could kill me in a flash, and it damn near did in the first 10 minutes."

At the time, Bromley was not reading river gauges, nor did he have a weather app on his phone, he said.

"The river gods, they gave me the cake, but they kept the icing on the cake, and they all said to me, 'Just remember your place in the world, boy.'" Bromley said.

Maybe the biggest highlight of the trip was the friends he made along the way, Bromley said.

"The only way I can pay this love that was shown to me forward is to share it," he said. "Maybe some old guy sitting in his living room will read this and say, 'If that old buzzard can do that, well heck, I'm going to do what I've been dreaming about the last 20 years.' Then, it's paid forward."

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Man completes nearly 3,000-mile canoe trip that started in Marshall