Black Nashville: 16 trailblazers, innovators, dreamers that helped shape Music City

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

From Nashville's earliest days, Black men and women have helped build the city.

They have created businesses. They have entertained. They have healed the sick. They have trained athletes who astonished the world. And they have fought to make the city fair and equitable for all its citizens.

Here are 16 Black Nashville leaders from the past that you should know.

DeFord Bailey (1899-1982): Musician

DeFord Bailey made his harmonica sing like a train on “Pan American Blues,” driving the Tennessee native to fame in the early days of country music. The first Black performer on WSM’s “Grand Ole Opry” broadcast, Bailey inspired harmonica players across the nation until a publishing dispute derailed his career in 1941. In 2005, Bailey was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. Last year, Nashville renamed Horton Avenue to DeFord Bailey Avenue in his honor.

Roll call: 24 Nashville Black leaders to know in 2024, from boardrooms and pulpits to classrooms

R.H. Boyd (1843-1922): Entrepreneur

In 1896, R.H. Boyd arrived in Nashville to launch a publishing house for Black Baptists. But the minister, a former cowboy who was born into slavery, also engaged in secular pursuits. He created the National Negro Doll Co. to give Black children uplifting images of themselves. He helped lead the 1905 Nashville streetcar boycott. And he was a founder of the One Cent Savings Bank, which still exists today as the Black-owned Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Co.

Eva Lowery Bowman (1899-1984): Entrepreneur

At the cosmetology school founded by Black millionaire Madam C.J. Walker, Nashville-native Eva Lowery Bowman learned about beauty and business. Bowman founded her own beauty and barber school to train others. She invented the “cooler curl.” And she was the first African American beauty inspector in Tennessee. An advocate for Black civil rights, Bowman made an unsuccessful bid in 1960 for the state House of Representatives, making her the first Black woman to run for the Tennessee General Assembly.

Dorothy Lavinia Brown (1914-2004): Doctor

When Dorothy Lavinia Brown decided to become a surgeon, there were no other Black female surgeons in the South. But she persisted and even became a clinical professor at Nashville’s Meharry Medical College. Brown was never deterred. In 1966, she became the first Black woman in the Tennessee General Assembly, resigning when the members failed to support expanded abortion rights. And Brown, who spent part of her childhood in an orphanage, became the first single woman in the state to be granted an adoption.

Walter S. Davis (1905-1979): Educator

Tennessee A&I State College in Nashville, the future Tennessee State University, had less than 700 students when Walter S. Davis was appointed its second president in 1943. When he ended his tenure 25 years later, the school had an enrollment of more than 5,000. Under Davis’ leadership, the college added faculty, departments and millions of dollars in campus expansion.

Darrell S. Freeman Sr. (1965-2022): Entrepreneur

In 2017, Darrell S. Freeman Sr. sold the tech company he built for more than $20 million. After getting so much, he spent the rest of his life giving back. Education mattered most to Freeman. He donated money for first-generation college students at Middle Tennessee State University. He also personally advised entrepreneurs and invested in many Black businesses.

Josephine Groves Holloway (1898-1988): Civic leader

When Nashville Girl Scouts leaders would not let her girls she worked with join, Josephine Groves Holloway was not deterred. She got ahold of the Girl Scout handbook and taught them the organization’s laws and oaths. In 1943, local leaders relented, and Troop 200 became the city’s first for Black girls. A year later, Holloway became a Scout leader herself. She would work for the Nashville Girl Scouts, promoting opportunities for all girls, until 1963. Camp Holloway, once a segregated facility, is named in her honor.

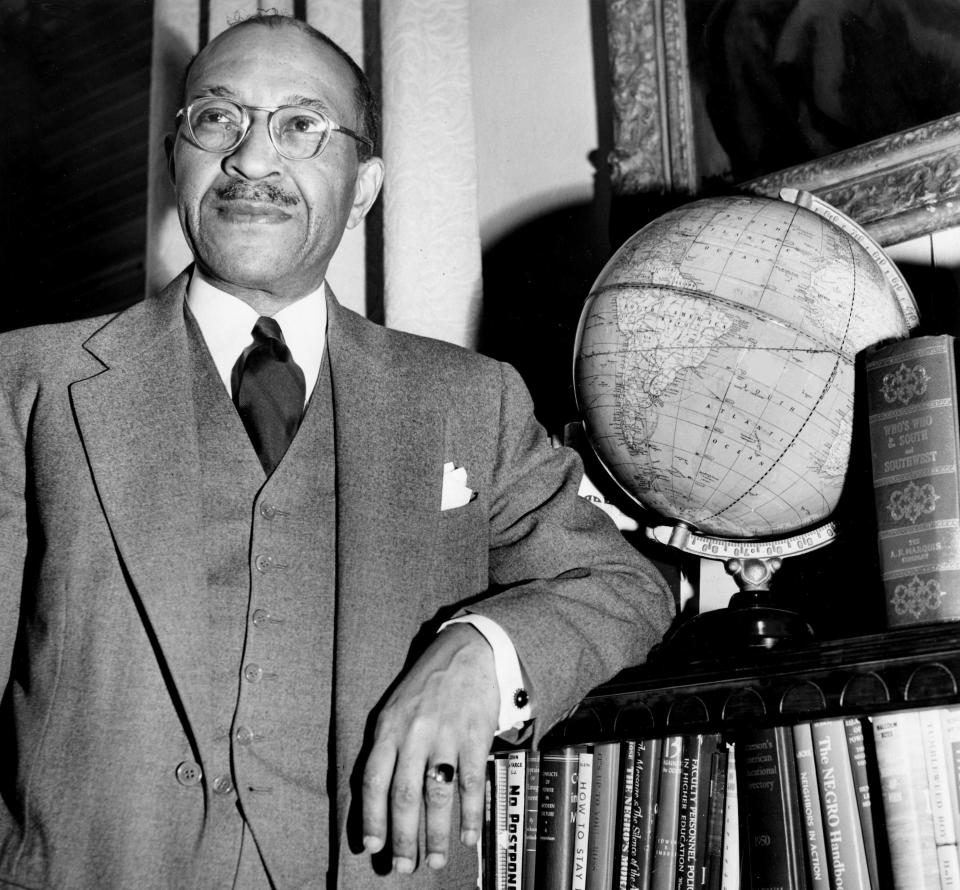

Charles S. Johnson (1893-1956): Educator

Fisk University was an intellectual center of the South in the 20th century. Leading artists and writers of the Harlem Renaissance came to lecture and teach. Founding ideas of the Civil Rights Movement were hammered out on the Fisk campus. Charles S. Johnson, a sociologist who came to the school in 1928, was crucial in bringing together those intellectuals in Nashville. Fisk from the start was a school for Black students. But not until Johnson was appointed president in 1947 did it have a Black leader.

Z. Alexander Looby (1899-1972): Lawyer

Z. Alexander Looby’s relentless campaign for justice was met with violence, when on April 19, 1960, the home of the lawyer and civil rights leader was ripped apart by dynamite. Looby had sought justice for unjustly accused Black defendants across Tennessee. He ended segregation at the Nashville airport’s dining room. In 1951, Looby along with Robert E. Lillard became the first African Americans elected to the Nashville city council since 1911. After Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, he sued to get the first Black student admitted to a white Nashville school.

Moses McKissack III (1879-1952): Architect

The first Moses McKissack was enslaved by a builder who taught him the trade. His son was also a builder. Moses McKissack III built not only homes, churches and libraries but also one of America's most successful construction and architectural firms. With his brother Calvin, he founded McKissack & McKissack, which built art deco office buildings, public schools and the Tuskegee air base. The family still runs the firm, now headquartered in New York.

James C. Napier (1845-1940): Politician

Dollar bills bore the signature of a Black man at the start of the 20th century. James C. Napier, a powerful Nashville politician, served as President William H. Taft’s Register of the United States Treasury from 1911-1913. A Nashville native with a law degree from Howard University, Napier was the first African American to preside over the Nashville city council. He made sure the city hired Black police officers, Black firefighters and more Black teachers.

Robert Renfro (late 1700s to 1816?): Tavern keeper

The first record of Robert Renfro, born in the late 18th century, was when he was sold as a slave in 1792. Two years later, Renfro, still enslaved, was granted a license to sell food and liquor in Nashville. The business became Black Bob’s Tavern. In 1800, a white man attacked Renfro, who pursued the case and won, an unheard-of outcome. Renfro was granted his freedom in 1801 and continued to operate his tavern in Nashville.

Theodore 'Ted' Rhodes (1913-1969): Athlete

The Nashville golf courses would not let Ted Rhodes play, so he mastered the game in the city’s parks using broken branches as flag sticks. Rhodes was a champion of the Black golf tour. In 1948, he played in the U.S. Open, breaking the color barrier in golf a year after Jackie Robinson had done so in Major League Baseball. Rhodes fought the PGA until the organization finally removed its “Caucasian-only clause” in 1961.

Rev. Kelly Miller Smith (1920-1984): Pastor

For Kelly Miller Smith, his church was a foundation for changing the world. The pastor of the First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill from 1951 until his death, Smith put himself and his church at the center of Nashville’s struggle for civil rights. From the start, he was part of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and its campaign of nonviolent protest. As the local NAACP president, he registered African Americans to vote. And after Brown v. Board of Education was decided, he sued so his daughter could be one of the first children to attend previously segregated Nashville schools.

Ed Temple (1927-2016): Coach

During the four decades Ed Temple coached the Tennessee State University women’s track and field team, 40 of his athletes competed in the Olympics. They won 13 gold medals, six silvers and four bronzes. Twice, in Rome and Tokyo, Temple was the coach of the U.S. women’s team. His TSU Tigerbelles helped lead America to a long reign of dominance in women’s track and field.

Avon N. Williams Jr. (1921-1994): Lawyer

In the legal battles for civil rights in Nashville, Avon N. Williams Jr. was always on the front lines. He fought to desegregate schools and universities, end employment discrimination and curb police brutality. One of his greatest victories came in 1972, when he convinced the courts to let the historically Black Tennessee State University take over the traditionally white University of Tennessee-Nashville. TSU’s downtown campus is named in Williams’ honor. Williams was the first African American elected to the Tennessee senate, where he served for decades.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nashville Black history: These Black leaders helped to shape city