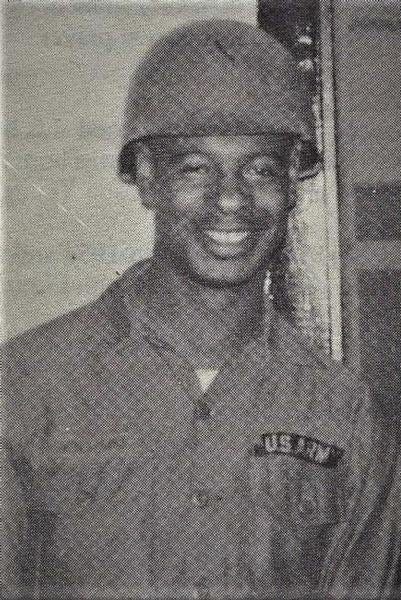

A Black soldier from NJ saved lives in Vietnam. Should he have received a Medal of Honor?

U.S. Army Specialist Four Lester Williams Jr. had been in Vietnam just seven months when all hell broke loose at Fire Support Base Rita one night in 1968.

North Vietnamese soldiers launched a surprise attack that Nov. 1, at around 3:30 a.m., bombarding the base with mortars and rockets. The U.S. troops fought back fiercely, firing shells and ammunition to ward them off. But those who made it past the return fire broke through the perimeter and stormed the base.

All-out fighting, bloody, chaotic — that’s how men recalled what went down that night.

Williams was in his bunker firing at enemy combatants, and then one tossed a grenade that landed near him. The 24-year-old jumped on the device, according to official accounts of the incident. He was killed in the ensuing blast, but he saved the lives of other men in the bunker that night.

Such acts of bravery have earned many men a Medal of Honor — the highest and most prestigious military decoration in the nation. But Williams, of the 8th Battalion, 1st Infantry Division, was not among those recipients.

Now, as the Department of Defense reviews acts of heroism by Black veterans who may have been overlooked for the medal in the past, Williams’ case may get new scrutiny.

Williams, who was from Bridgeton in South Jersey, was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest military decoration, after his death. He should also be considered for the Medal of Honor, U.S. Sens. Cory Booker and Bob Menendez and Rep. Jeff Van Drew wrote in a draft letter they plan to send to President Joe Biden.

“As the Department of Defense reviews all Service Crosses awarded to African American veterans during the Vietnam War, including Specialist Lester Williams, we urge you to properly recognize his supreme sacrifice and award him the Medal of Honor,” they wrote. “His distinct valor and gallantry is well deserving of this award as he selflessly gave his own life so that others could live.”

‘Extraordinary heroism’

Drafted into the Army, Williams started his tour April 30, 1968. Fire Support Base Rita, near the border with Cambodia, was situated along a main supply route used by the North Vietnamese.

“There were a bunch of fire bases in that area, and it was a constant battle,” said Joseph Plunkett, a generator mechanic who served in the 1st Infantry Division at the base. “We were blocking where they would bring in their supplies.”

They often faced rocket and mortar fire, but nothing like that night, Plunkett said.

'Welcome home': North Jersey vet's book focuses on his time as a 22-year-old in Vietnam

When the attack happened, everyone opened fire in what was called a “mad minute,” and then paused to reload.

“When that happened, that’s when the NVA [North Vietnamese Army] attacked. Some sappers were already in the wire," Plunkett said, meaning combat engineers had gotten past the defensive wire. "An armored personnel carrier in front of me — it blew up.”

Plunkett did not learn about Williams’ act of heroism until after his service, when he read the citation for the Distinguished Service Cross granted to Williams on Dec. 30, 1968. According to that account, Williams, as a cannoneer, came under fire and ran to the bunker, where he aimed his machine gun at advancing North Vietnamese soldiers.

“Suddenly an enemy grenade landed in the bunker,” states the citation. “He immediately threw himself upon it to save the lives of his comrades and was killed by the explosion. Specialist Four Williams' extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty, at the cost of his life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.”

Army medic Mack Easley, who responded to the scene, found Williams with wounds to his throat and hands. The wounds indicate he may have been on his cot when the grenade landed, and that he tossed it and was hurt when it exploded, he said.

“I’m sure he threw it out of the bunker because he didn’t want to die,” Easley said. “He didn’t want anyone else in the bunker to die. He probably was wishing he wasn’t there at that time.”

Through the night, the U.S. soldiers fought fiercely to repel the attack. When it was over, 14 U.S. troops were killed and at least 33 wounded.

Honors long overdue

Bill Davenport, a Vietnam veteran from Cape May County, hosts a weekly radio show called "Welcome Home Veterans," with a segment recognizing the birthdays of people killed in the war. If a person is local to South Jersey, they get an expanded segment.

That’s how he learned about Williams.

“From the time I was in boot camp, you jump on a grenade, you get a Medal of Honor,” Davenport said. “I have found dozens of cases like that. Around that time, I learned about the directive the Department of Defense gave. I thought this guy deserves a Medal of Honor. I started writing letters and contacting representatives.”

Fighting a double war: A Black journalist in WWII

President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation creating the Medal of Honor for the Navy in 1861 and for the Army in 1862. Since then, 3,516 people have received the medal. Only 94 recipients have been Black.

“The racial disparity is troubling and raises the questions of whether Black service members were unjustly denied recognition for valor in combat,” Edward Lengel, chief historian for the National Medal of Honor Museum in Arlington, wrote in a column for The Dallas Morning News two years ago.

“Racism’s role in the undue denial of recognition of Black service members for valor is unquestionable, and the U.S. armed forces have formally recognized the problem,” Lengel wrote.

One of the Black recipients of the Medal of Honor was awarded for his bravery in the same battle as Williams. Charles C. Rogers, a lieutenant colonel at the time, rallied his battalion to defend the base despite being wounded three times that night. He survived and received the award in 1970.

In August 2021, the Department of Defense announced an effort to review second-level military decorations given to African Americans and Native Americans who served in the Korean and Vietnam wars and whether they warranted a Medal of Honor. A similar review has been done for World War II veterans.

Plunkett, the generator mechanic, was not surprised to hear that Williams’ case was getting new scrutiny.

“You hear all these stories about people falling on grenades who got Medals of Honor, and this is comparable, absolutely comparable,” Plunkett said. “It’s the same kind of thing. You can’t question the valor. You can’t question the above and beyond.”

The following Army solders were killed in action at Fire Support Base Rita in Vietnam on Nov. 1, 1968:

Cpl. William K. Alameda of Waimanolo, Hawaii, age 24.

Spc. 4 William P. Alongi of Elmwood Park, Ill., age 25.

Sgt. Thomas Wylie Bayonet of St. Petersburg, Fla., age 21.

Spc. 4 Thurl Guy Carter III of Hayward, Calif., age 21.

Sgt. James Michael Ciupinski of Chicago, Ill., age 19.

Spc. 4 Charles Grey Costin of Warsaw, N.C., age 18.

Spc. 4 Ronnie Courtney of Tahlequah, Okla., age 21.

Sgt. James Eddie Graves of Drake, Ky., age 21.

Spc. 4 Wayne Kevin Laine of Walnut Creek, Calif., age 20.

Pfc. James Emmett Martin of Portland, Ore., age 20.

Sgt. Wendell D. McBurrows of Abbeville, Ga., age 25.

Spc. 4 Marvin Norbert Propson of Hilbert, Wis., age 19.

Spc. 4 Lester Williams Jr. of Bridgeton, N.J., age 24.

Staff Sgt. James R. Norris of New Haven, Ky., age 22.

Source: Compiled by Joseph Plunkett via The Coffelt Database of Vietnam Casualties

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Medal of Honor: NJ soldier's heroism in Vietnam could get new review