A Black teen from RI was sentenced to death in New York. His hometown tries to save him.

The first few decades of the 20th century were perilous times for Black men in America, as two Rhode Islanders would learn all too well.

This was the height of the lynching era, when all but five states experienced these extrajudicial murders and when politicians across the land debated what could — or even should — be done to stop them.

But the judicial system was not much safer. Black defendants saw courts rigged against them, especially in death-penalty cases, with white prosecutors charging them with more serious crimes, with white defense lawyers representing their clients less zealously and all-white juries convicting on flimsy evidence. The 1930s saw the highest number of executions of any decade in U.S. history, and more than two-thirds of the convicts put to death were Black.

"The early 1900s coincided with a lot of racial violence," Robin Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said recently. "In some respects, capital punishment came to replace lynching as a way of controlling, subduing and restricting the activities of Black people."

This series tells the stories of two young Rhode Islanders caught in the eye of this storm. It tells how fellow Rhode Islanders — Black and white — stood behind them when their lives were on the line.

While it recounts events from a century ago, "Legal Lynching" offers lessons that are fresh today.

"It was inspiring to see that so many groups did gather around and that the community really exercised its voice in demanding something more just happen here," said Megan Byrne, staff attorney with the Death Penalty Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. "We as a community do still have voices that can be heard, and I think it's a good lesson because even in this situation — it's the early 1900s and so many things are unfair and we might feel so powerless — but even then, people were able to organize and make their voices heard."

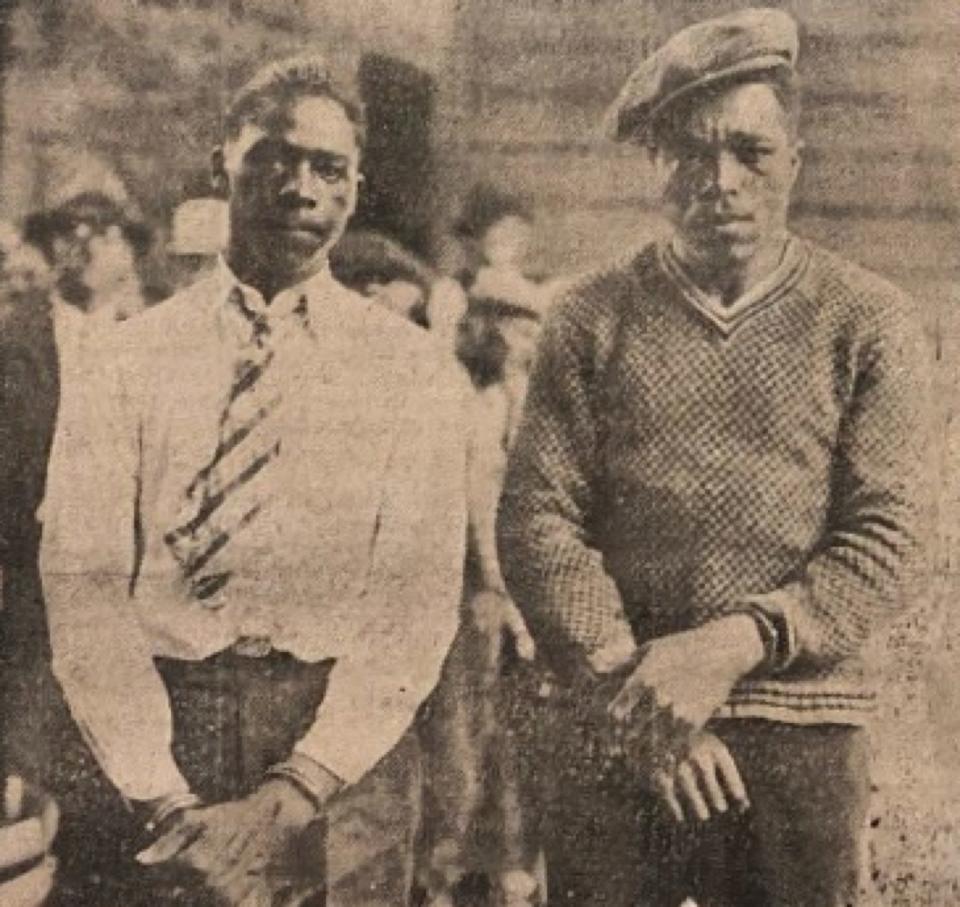

Below is the story of one of those men, Herbert Johnson of Barrington.

Chapter 1: Herbert Johnson, Black teen from Barrington, is hunted down by an upstate New York posse

SCHOHARIE, N.Y. – Herbert Johnson, a Black teen from Barrington, Rhode Island, heard gunfire all around him in the wooded hills overlooking Schoharie village.

Closing in was an armed posse several hundred men strong, and Herbert knew that many – maybe most – wouldn’t hesitate to shoot him dead.

Already shot at twice, Herbert tried to navigate a countryside laced with brooks and ravines unlike anything he had known back in Rhode Island.

But a deputy sheriff spotted Herbert sneaking through the woods and leveled his rifle at the teenager and pulled the trigger.

The deputy fired one shot. Then another. And another.

“Stop shooting at me, boss!” Herbert yelled, thrust his hands above his head and stepped out from behind a tree, trembling at the thought of what would happen next.

Herbert was heading from his mother’s house in Chicago to his father’s in Barrington

The day before, Herbert had set out from his mother’s house in Chicago, a city that she'd characterized as so dangerous that he'd bought a gun before going to visit her. He tucked that same gun into his sock when he left the Windy City.

He was headed back East, to Barrington, where his father was going to set him up with some land. The trip had been going well. He stopped in Erie, Pennsylvania, and picked up a hitchhiker, another young Black man a few years older than himself named Henry Roosevelt Walker.

But the car’s fan belt let go somewhere along the way. That ordinarily trivial mishap touched off a chain of events that would prove fatal.

When the car’s engine overheated in Sharon Springs, New York, a state trooper said Herbert and Henry were acting suspiciously.

While they weren’t the only Black men in Schoharie County that July day in 1930, they were close to it. Three months earlier, the U.S. Census had counted only 62 Black men in a county of nearly 20,000 people.

Herbert and Henry were arrested at about 8 a.m. and dragged before a justice of the peace, each sentenced to 15 days in Schoharie County Jail — Herbert for driving without a license, Henry for vagrancy.

Without being searched for weapons, Herbert and Henry were loaded in the back of a car by the state trooper and a deputy sheriff for the hour-long drive to the county jail and courthouse in Schoharie village. Halfway there, Deputy Morgan Lynk dropped the trooper off and continued on alone with the two prisoners.

Herbert, just 18 years old and with a seventh-grade education, started to panic: If he were found to have a gun, things would only get worse. Pulling it from his sock, he hid the pistol under an overcoat folded in his lap. He thought about tossing it out the car window but, despite the July heat, the windows were rolled up.

Before he knew it, the car pulled up between the limestone courthouse, which had stood in the village some 60 years, and the Parrott House hotel.

Lynk got out of the car, went around to the other side, let Herbert and Henry out and directed them into the courthouse and up to the second-floor sheriff’s office.

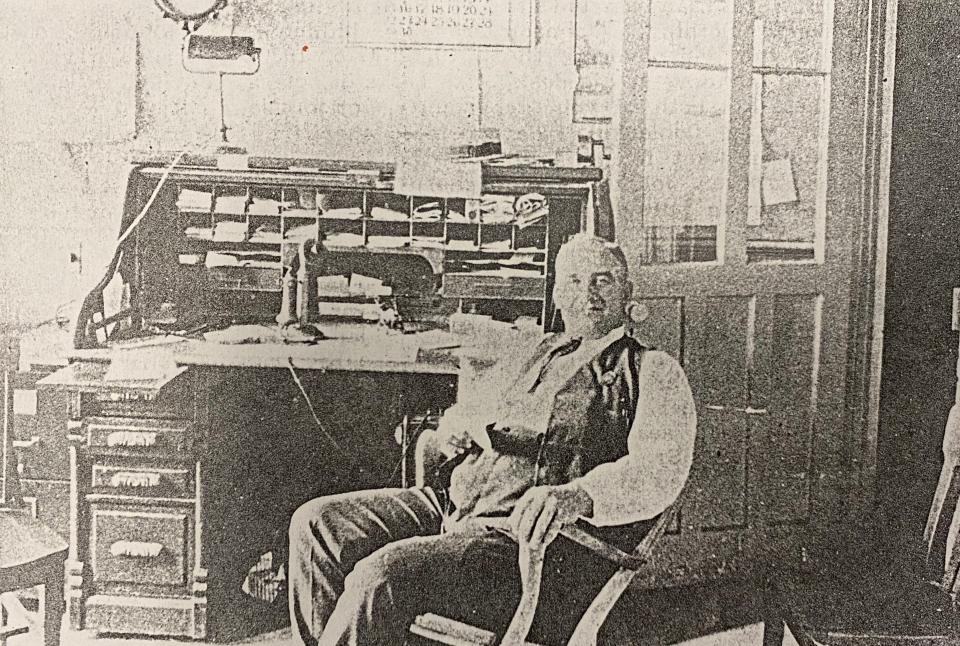

Sheriff Henry Steadman was sitting at his desk when Herbert and Henry entered shortly before noon. The sheriff directed them to sit in chairs.

Lynk walked in and handed Steadman the court paperwork and then sat on a windowsill on one side of the office.

“Have they been searched?” Steadman asked his deputy.

“No,” Lynk answered.

“Stand up,” Steadman told Henry. “Empty your pockets so I can search you.”

Herbert knew he had to do something about the .25-caliber automatic pistol still under his overcoat. He knew he would be searched next, and the gun would be discovered at any second. He had to make up his mind. He didn’t have time to come up with a good decision. He had to get out of that office.

Just as Steadman finished with Henry, Herbert stood up, pulling out the small, black gun and pointing it at the sheriff.

“Move over there!” he ordered. “Next to him!” He glanced toward Lynk, still sitting on the windowsill.

Nobody moved much.

Steadman opened his desk drawer, where he kept his gun. Then he closed the drawer and opened it again. And shut it once more.

A full minute passed, maybe two.

Herbert had a clear shot, but he didn’t take it.

Suddenly, both lawmen moved at once.

Lynk slid toward the doorway, blocking it.

Steadman lunged toward Herbert, reaching for the gun.

As soon as Steadman touched Herbert’s hand, the gun went off.

Steadman clutched his side.

“He shot me,” he said, and then grabbed Herbert’s right hand again, pushing it and the gun upward, away from him.

Herbert yanked his hand away and darted toward the door.

Lynk stepped aside slightly, leaving just enough room for Herbert to dash through.

As Herbert ran down the stairs, Steadman found the gun in his desk and gave chase.

Sheriff’s wife hears commotion

One of the perks of the job in Schoharie County was an apartment for the sheriff and his family, in the courthouse, near the sheriff’s office.

Flora Steadman was in the kitchen of the apartment when she heard the gunshot, followed by shouting.

She rushed to the front door of the apartment just in time to see the 5-foot-5, 120-pound Black teenager racing down the stairs toward the courthouse door, followed by her husband, who paused on the stairs to fire a shot at the fleeing youth.

The sheriff was losing steam as he went. When he made it to the stone front steps of the courthouse, he stopped and sat down.

“Kill him! Kill him!” Steadman shouted to passersby. “He just shot me.”

Lynk tells a different story

Lynk would tell the same story of what happened in the sheriff’s office, right up until Herbert pulled the gun. Then, the deputy added damning details.

“Stick ’em up, the both of you! Or I’ll kill you both!” Herbert yelled, according to Lynk’s account.

Herbert pointed the gun at the sheriff, and then at Lynk, and then back at the sheriff. He kept moving it back and forth, said Lynk.

As the gun moved back to Lynk again, Steadman started toward Herbert.

Lynk heard the gun go off.

Then Herbert ran out, knocking the deputy over, and the sheriff pursued, Lynk said.

Lynk takes up the chase

The deputy found Sheriff Steadman outside, leaning against the courthouse steps.

“Give me your gun!” he shouted to his boss.

Lynk ran between the Parrott House and the courthouse, toward the back of the building, where he saw Herbert climbing over a stone wall.

Lynk fired the sheriff’s gun at him but missed.

Lynk climbed the wall and chased Herbert toward the hill behind the courthouse, firing four more times before Herbert raced off toward the woods.

The deputy then headed back to the courthouse to check on the sheriff.

Sheriff organizes pursuit of gunman

Steadman, a popular auctioneer who been elected six months ago to his first term as sheriff, stayed put on the courthouse steps for a good five minutes after Lynk chased after Herbert. The sheriff organized the beginnings of a posse as a crowd gathered in front of the building.

Flora Steadman urged her husband to go up to the apartment, but he would have none of it.

“Don’t be afraid,” he told her. “My back hurts, but not bad. I’ll be all right.”

When Lynk got back, he found Steadman still on the steps, his left hand holding his side, covered in blood.

Two doctors in the crowd joined with Flora Steadman in persuading the sheriff to go inside.

“Tell the men to get the Negro,” he said, before his wife and the doctors helped him up to the apartment.

Steadman lay on a sofa in the living room as the doctors tended to him. His family gathered around and worried. His 14-year-old daughter, Thelma, and 19-year-old son, Harold, were at his side.

Dr. Herbert J. Wright bandaged the gunshot wound and cleaned the sheriff’s left thumb, which had powder burns and a grazing wound where he had reached for the gun.

After about 20 minutes, the doctors decided that the sheriff needed to go to Ellis Hospital, some 30 miles away in Schenectady. Thelma and Harold said they wanted to ride with their father. Flora agreed. She said she would wait for her 24-year-old daughter, Dorothy, to arrive from the next county over, and then they could all meet at the hospital.

Flora was confident her husband would survive.

Then Steadman walked down the stairs from the apartment and out to Wright’s waiting car, driven by Perry E. Badgley Jr., the 43-year-old owner of a Schoharie candy shop.

On the way to the hospital, the sheriff told Badgley that Herbert’s gun had gone off when Steadman struck the teen’s hand, trying to knock the gun away.

The posse gets its man, wants blood

As Steadman headed to Schenectady, as many as 400 armed villagers added to the state troopers scouring the hills outside Schoharie village.

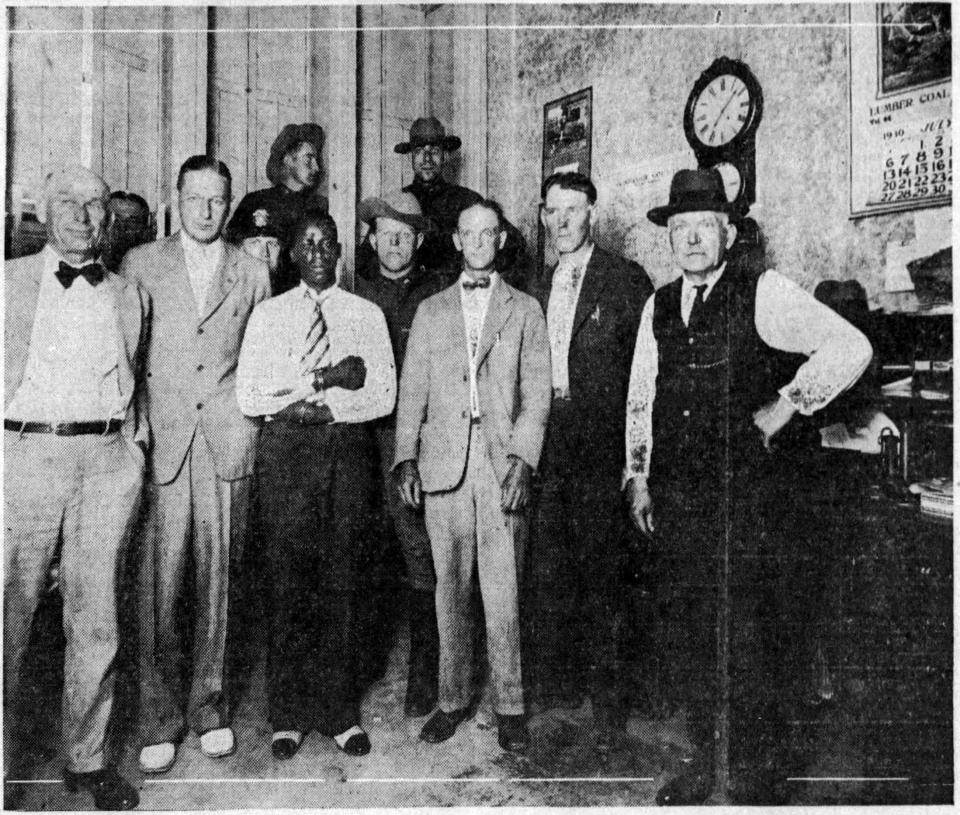

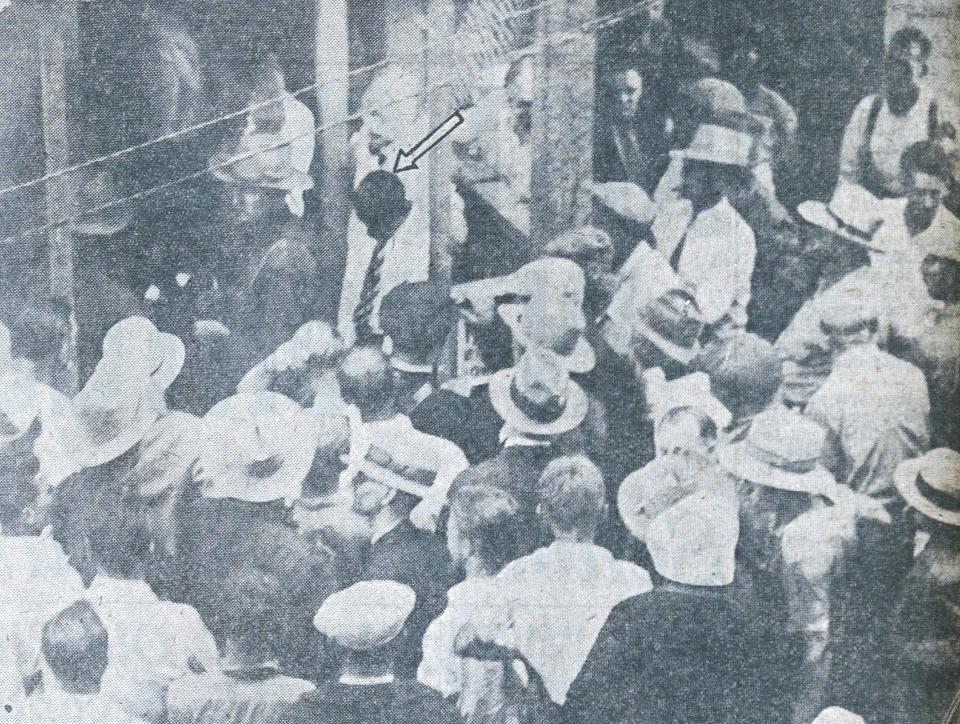

Back in the village, a teeming crowd pressed close to the courthouse when Herbert was brought back, more than three hours later.

“Lynch him!” people yelled from the safety of the crowd. “Show him the rope!”

Troopers encircled Herbert and ushered him into the relative safety of the jail.

He wouldn’t be there long.

Doctors fight to save the sheriff’s life

At Ellis Hospital, the sheriff, suffering from shock and internal bleeding, was rushed into the operating room by Dr. Edwin M. Stanton.

When Stanton opened the sheriff, he found that his abdomen was full of blood and that the bullet had torn through Steadman’s liver. He packed the hole in the liver with gauze and closed him up without probing the sheriff’s body for the bullet.

Doctors gave Steadman a 50-50 chance of making it.

Herbert taken from jail

In the late afternoon, Herbert was taken from the jail and handcuffed. Then he was put into the back of a car, guarded by two state troopers.

Herbert wasn’t sure where they were headed — or even what day it was. It had been so long since he'd last slept. He kept dozing off in the car, only to be roused by one of the troopers slapping him in the face and telling him to stay awake.

The state troopers and Schoharie County District Attorney Sharon J. Mauhs led Herbert to Steadman’s hospital room. The teen stood at the sheriff’s bedside, in handcuffs.

“That’s the man,” Steadman said weakly. “That’s the man.”

Herbert was led back out to the car, where the DA questioned him for about an hour, until 7 p.m., before heading back to the Schoharie jail.

As sheriff dies, Herbert’s life is in danger

At 4:20 a.m., some 16 hours after he was shot, Sheriff Henry Steadman, 51, died of blood loss, with his wife and eldest daughter at his side.

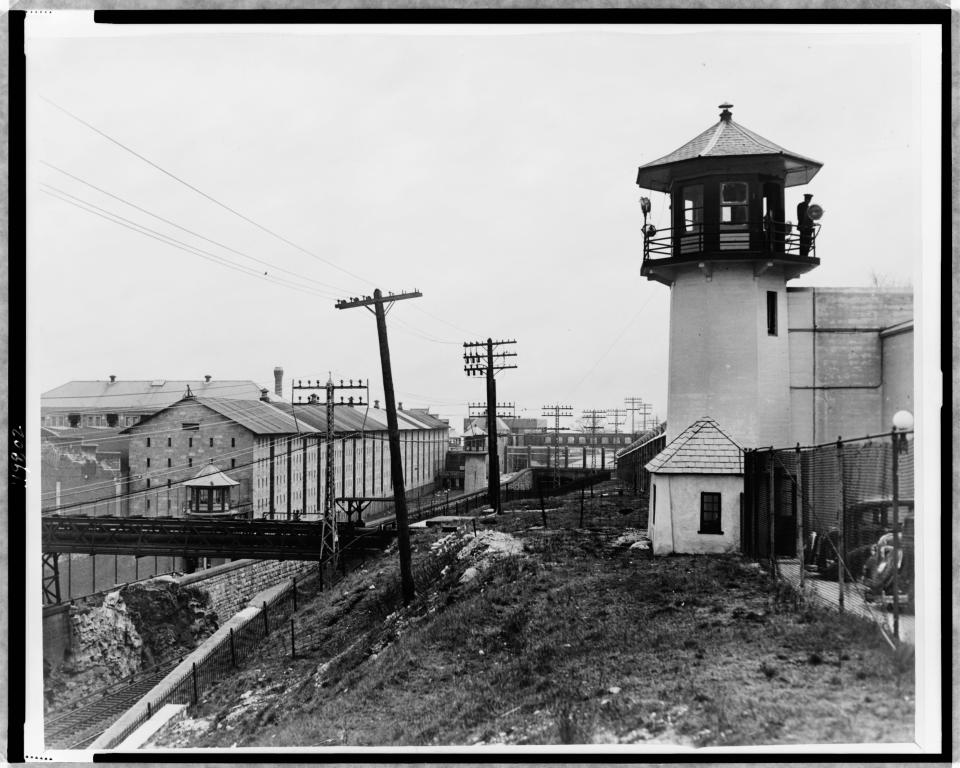

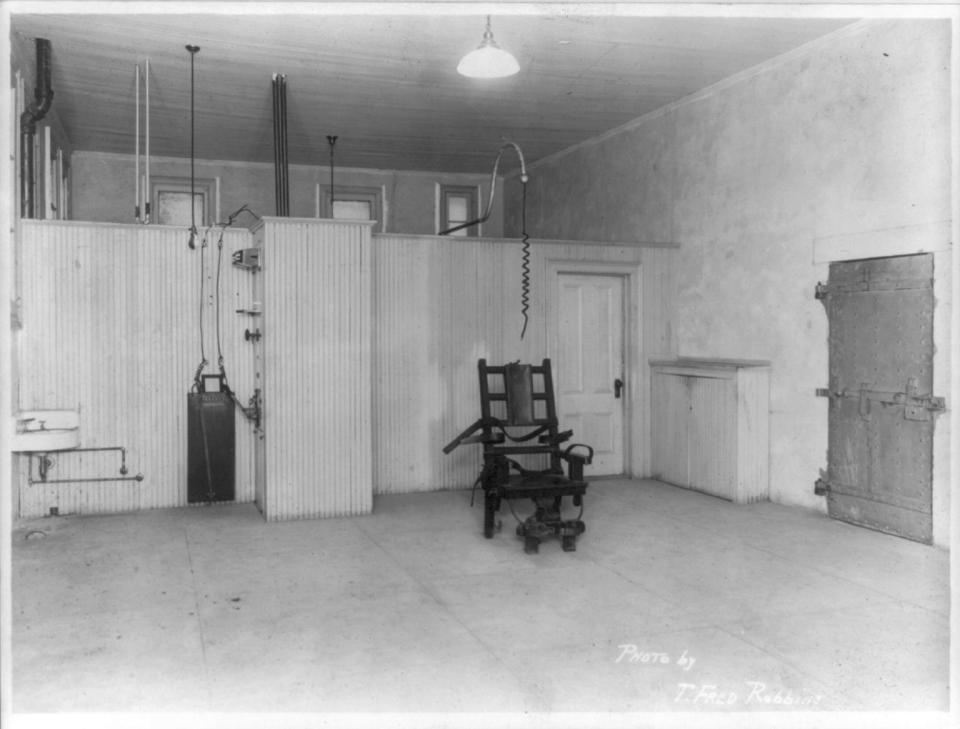

The charge against Herbert was upgraded to first-degree murder. Herbert now faced the death penalty, which, in 1930 New York, meant the electric chair in Sing Sing Prison.

When the news spread that morning, the calls to lynch the Rhode Island teen grew louder.

State troopers and deputy sheriffs doubted they could keep Herbert safe in the Schoharie jail.

Chapter 3: Herbert Johnson never had much of a chance in life

BARRINGTON — Friends would one day rally around Herbert Johnson, recalling a basically good kid, though far from perfect, seemingly shortchanged by life at almost every turn, right from the start.

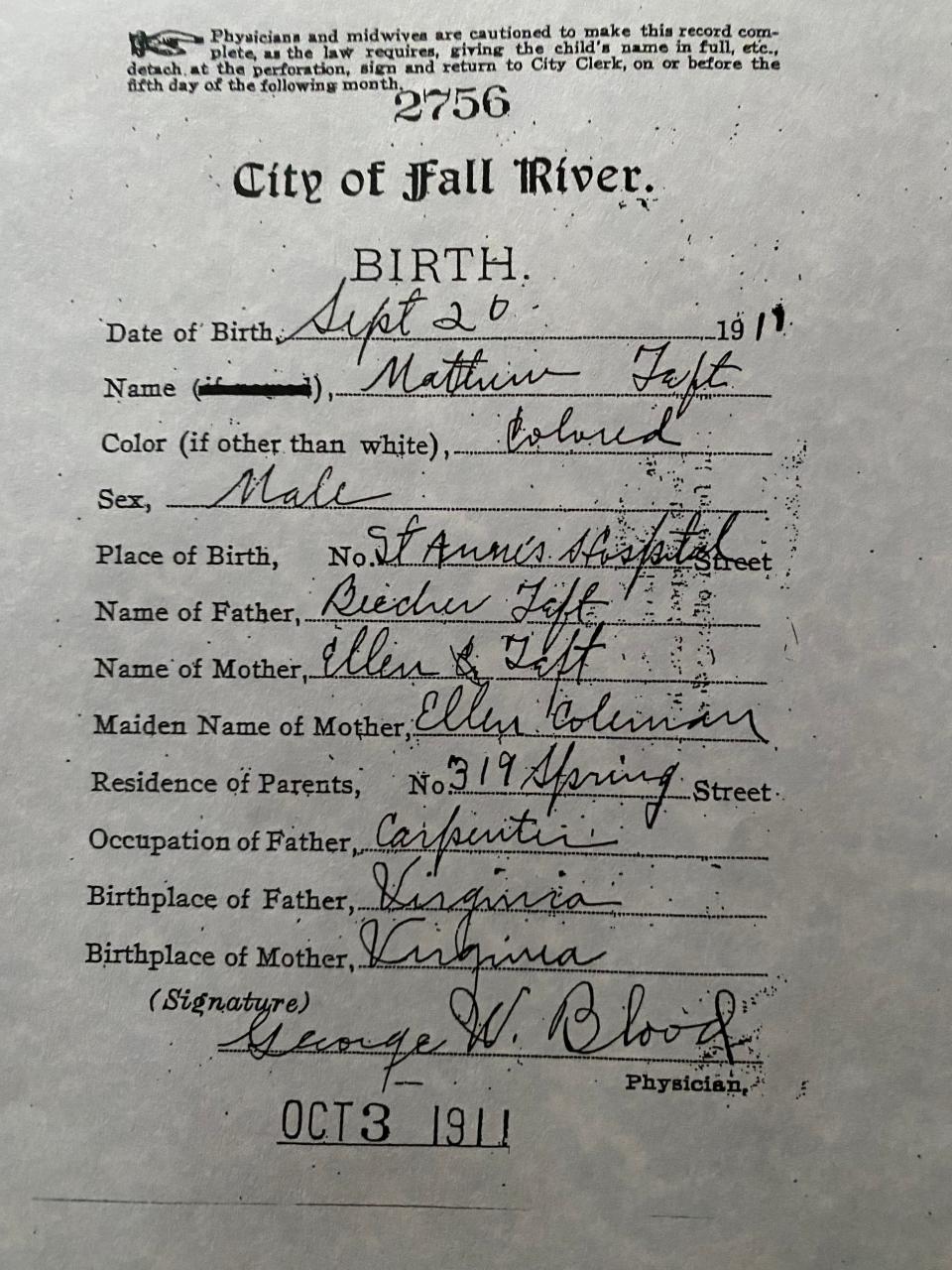

When he was born, on Sept. 20, 1911, in St. Anne’s Hospital in Fall River, Massachusetts, Herbert didn’t even have his own name.

Although he was the son of Pheling and Ellen Johnson, of Barrington, his birth certificate listed his parents as Beecher and Ellen Taft. It gave his name as Matthew Taft, and said he was “Colored.”

But, other than Herbert’s birth certificate, records of a Beecher Taft, either in Massachusetts or Rhode Island, are lacking. Did he even exist?

Why would Ellen lie on Herbert’s birth certificate?

When Herbert was born, Pheling was married to another woman, Delia Annie Johnson.

Had Ellen, who gave her home address as that of a Fall River boarding house run by a Black woman from Georgia, moved across the state line into Massachusetts to hide an illicit pregnancy?

What else did Pheling have to hide?

Pheling, who was born in Virginia, either during or shortly before the Civil War, had been suspected of attacking his first wife, Delia, several times.

The couple had moved to Barrington from Virginia in the 1880s. He found work harvesting oysters, sometimes supplementing his income by collecting junk, which he often kept piled near his Spring Avenue home.

Delia – but not Pheling – bought more than an acre of land next to Allins Cove, on the edge of Bay Spring village, in 1908.

The Johnsons were one of two Black couples in the town of 2,500 people.

Three times, from 1899 to 1911, Pheling had been charged with assaulting Delia. Twice, he was convicted and ordered to pay $5, a couple of days' pay at the time.

In 1912, it looked like he went too far.

Fellow oysterman Owen Harkins found Delia lying unconscious in a meadow near the Johnsons' home one December night. Harkins called the police chief, who summoned a doctor from nearby Riverside. Delia was breathing but couldn't be roused. She was taken to Rhode Island Hospital, where her condition remained a mystery.

After his wife was found, Pheling told neighbors that he and Delia had spent most of the previous day with friends in Providence. He said she had left the city on the 9:30 p.m. electric trolley, while he stayed until the 11:30 trolley. He told everyone that, when he got home around midnight, Delia wasn't there and that he went to bed around 1 a.m.

By the next morning, Pheling had disappeared from Barrington.

The following afternoon, Delia died in the hospital, having never regained consciousness.

The police knew of Pheling's violent history and suspected foul play.

But, just as quickly as suspicion settled on Pheling, it evaporated. He turned up in Providence later the same day he had disappeared. And, on Dec. 4, 1912, two days after she died, the medical examiner ruled Delia had died of a cerebral hemorrhage, with “no marks of violence.”

At the time of her death, Delia and Pheling had been married 30 years, but they'd never had children together.

With Delia gone, a different life for Herbert

After Delia's death, Herbert's life changed, but not for the better.

On April 1, 1915, with a second baby on the way, Ellen married Pheling. Two months later, Herbert’s younger brother, Toussaint Louverture Johnson, was born at home in West Barrington.

But Ellen rarely lived with Pheling, and Herbert bounced back and forth between his parents' homes, except when they got tired of him and shipped him off to live with relatives in Massachusetts or Virginia. Meanwhile, Ellen herself was on the move a lot, from Barrington to Providence to East Providence to Boston.

The summer Herbert was 5, Ellen was pregnant again, with a daughter. But, on March 15, 1918, Herbert's baby sister was stillborn, and doctors blamed Ellen for working too much.

Two years later, when another baby was on the way, Ellen left Barrington and moved to a rooming house on Providence's Thayer Street. She took Herbert with her, but left Toussaint in Barrington with Pheling.

Another baby brother is more than Herbert can take

On June 18, 1921, Ellen gave birth to Booker T. Washington Johnson. That left her with little time to spare for Herbert.

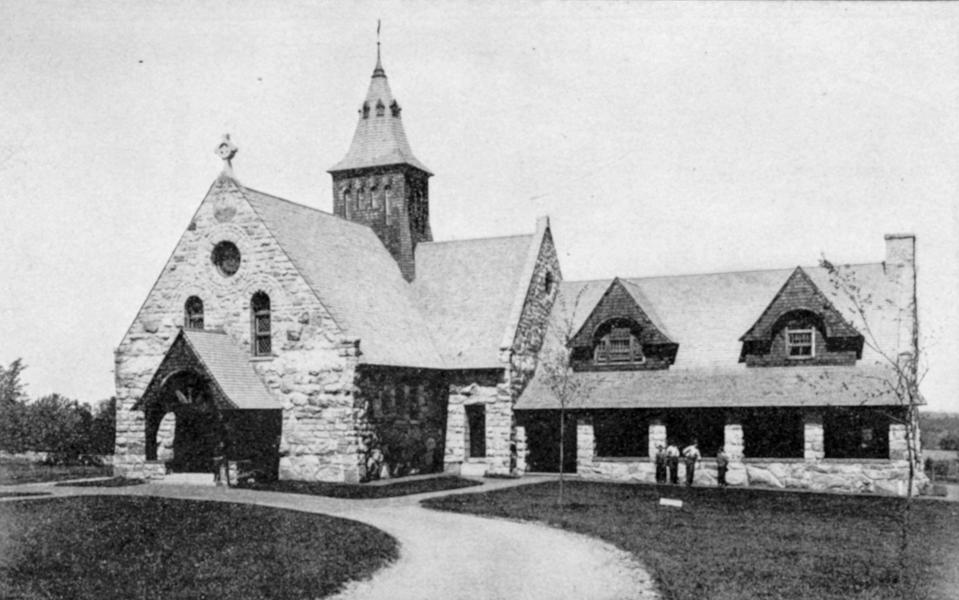

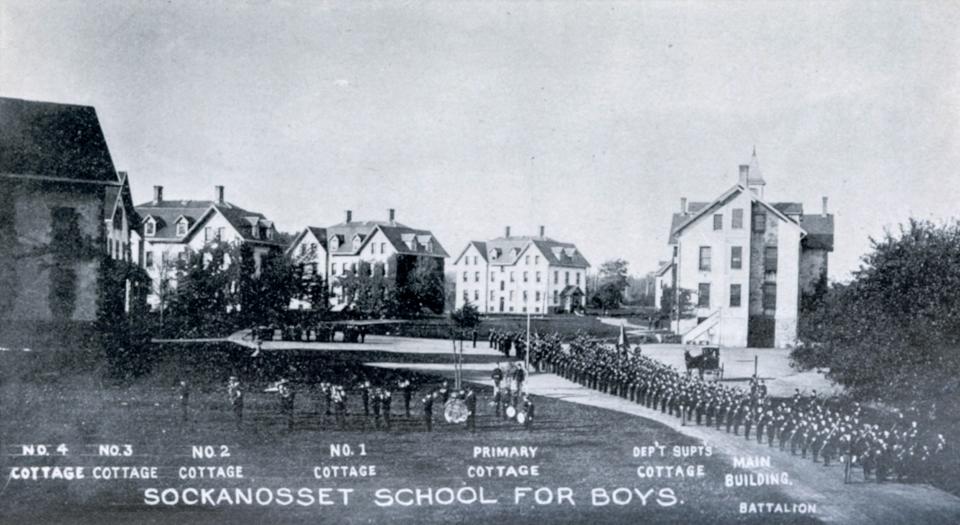

Starved for attention, Herbert began acting out. He skipped school, and the truant officer sent him to the Sockanosset School for Boys, the state’s reform school, a forerunner of the Rhode Island Training School. Herbert stayed there a month.

A prosecutor would later describe the truancy as Herbert's first “conviction” and the beginning of “a life of crime.”

Back with Ellen, Herbert pulled a fire alarm — he was bored and wanted to see how quickly the fire engines could climb Providence’s hills. Two more months at Sockanosset.

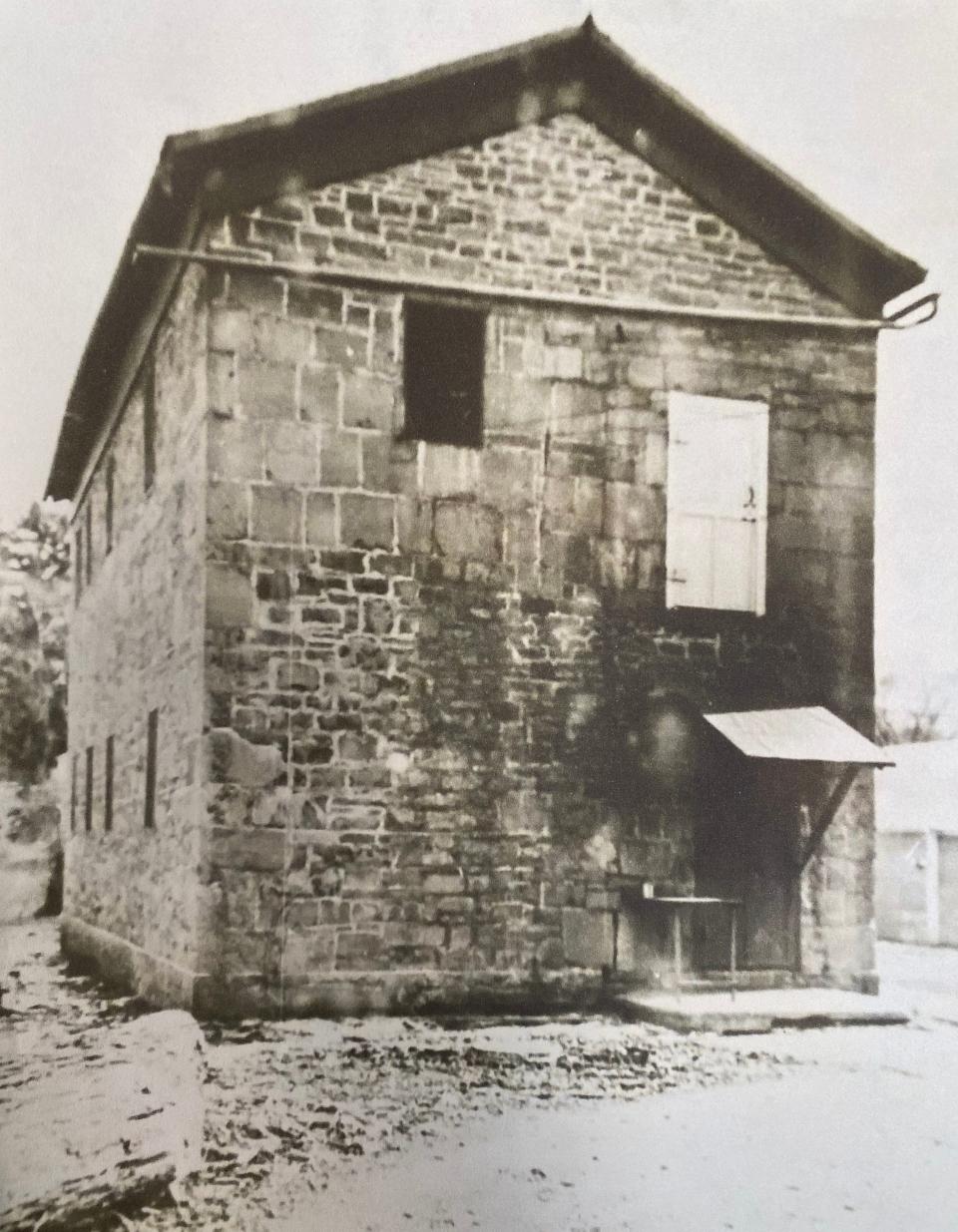

Ellen moved to Chicago with Booker, leaving Herbert to live with Pheling, in a home that could charitably be described as a shack. It was built of stacked-up mattresses and tarps. A photo of it had once been on the cover of a pamphlet, illustrating the worst possible environment in which to raise a child.

Herbert stole a bicycle. Six more months at Sockanosset.

Roy L. McLaughlin, superintendent of the reform school, became fond of Herbert.

“Johnson was the best-hearted kid in the town,” McLaughlin later said. “We thought he was too good to be in a state correctional school.”

But Herbert had not been a happy young man.

“I didn’t want to have anything to do with my father,” he said later.

And Ellen didn’t fare much better in his eyes. “I didn’t want to stay home with my mother, and I just wanted to keep on the go all the time.”

Where will Herbert go next?

When it came time for Herbert to be discharged from Sockanosset, in March 1926, McLaughlin and his staff knew that the youth shouldn’t be sent back to live in Pheling’s Barrington shack.

Instead, he was committed to the state’s orphanage, formally known as the State Home & School for Dependent & Neglected Children, on April 9, 1926.

Court papers sending Herbert to the orphanage said Pheling “lives in a hovel under very improper conditions and is not a fit person to have the custody of minor children.” And, they added, Ellen had deserted her family.

The papers made no mention of Herbert's younger brother, who stayed with Pheling.

The state orphanage, on what would become the Providence campus of Rhode Island College, offered Herbert more freedom. He attended Providence public schools. But, it wasn’t enough for the young man who wanted to “keep on the go.”

On May 14, a little more than a month after he got there, Herbert ran away from the orphanage. He returned the same day to a stern warning: Run away again, and it’s back to Sockanosset.

A trip to New York City?

Nine months later, after a matron at the orphanage had given him a beating, he ran away with another boy.

They aimed for New York. “I didn’t know nothing about New York City,” Herbert said, “and I wanted to see New York City.”

But, they wound up in Boston instead, and then hitchhiked to Pawtucket and walked to Providence, where they spent a chilly February night sleeping outside on the docks.

The next morning, after warming themselves in the train station, they made their way to East Providence, to the house of the other boy’s aunt, and agreed to return to the orphanage.

But Herbert had used up his chances there. On Feb. 14, 1927, it was back to Sockanosset.

He would be there almost a year and a half, time that proved productive. He learned to be a waiter, fit to work in fancy hotels, and he played in the school band.

On July 28, 1928, Herbert was discharged from Sockanosset, a couple of months shy of his 17th birthday.

Herbert is drawn to the sea — and to his mother

Ellen was still in Chicago with Booker and had sent Herbert letters at the reform school, warning him to stay away from that city. So Herbert tried to live with Pheling in Barrington, but within a month, he got into a fight with Toussaint and realized he had to leave.

After living on the streets in Providence for a week looking for work, he made a move that would set the stage for the rest of his life:

“I decided to get a job out at sea,” he said. “I always wanted to see what the sea was like, because my father had also been to sea.”

He signed on as a sailor aboard the SS Volusia, of the Merchants & Miners Transportation Company, making runs from Providence to Norfolk, Virginia, to Baltimore and back again.

While he was on the ship, Ellen kept writing him and telling him to stay away from Chicago.

“My mother had gone to Chicago in 1925, and that was the last I had seen of her,” he said. “I told my mother I was coming anyhow, because I wanted to see her.”

She tried to dissuade him, telling him again that the Windy City, home of gangster Al Capone, was a dangerous place.

He took that warning to heart, but not in the way she had intended.

In March 1929, when the Volusia was docked in Baltimore, he quit. He collected his final pay and went ashore. His first stop was a pawn shop, where he sold his sea clothes to raise money. Then, he went to another pawn shop, on East Pratt Street, with his mother’s warning in mind.

He paid $12.50 for a .25-caliber automatic pistol and a box of ammo.

Chicago turned out to be less dangerous than he'd expected. He never needed the gun, except one day when he fired it to celebrate the Fourth of July.

Herbert found work in restaurants during the cold months, and as an iceman during the warmer ones.

He also once stole a box of socks and served 60 days in the Cook County House of Corrections.

His father calls Herbert home to Rhode Island

In July 1930, Pheling, who wanted to set his son up with some of the land he had inherited from Delia, asked Herbert to come home to Barrington.

In the pre-dawn hours of Sunday, July 13, Herbert crawled into an open basement window of an apartment on Chicago’s South Side.

Philip McPhail was sound asleep in the living room of the apartment. Herbert searched through the man’s pants pockets. He found $58 in cash, a gold watch, a watch chain, a knife and keys to a car. Parked on the curb outside the apartment, he found a brand-new Graham-Paige sedan that fit the keys. He drove it away but didn't leave Chicago for almost two days.

In the first few minutes of Tuesday, July 15, Herbert tucked his loaded pistol into his sock, climbed into the car and headed east, toward Rhode Island. On his way out of town, he stopped at a gas station to pick up a map and ask directions. He was told to follow Route 20 from Chicago, which would take him all the way to Boston.

Fatefully, it would also bring him through Schoharie County, New York.

Chapter 5: Al Pearson won't be stopped when he knows he's right

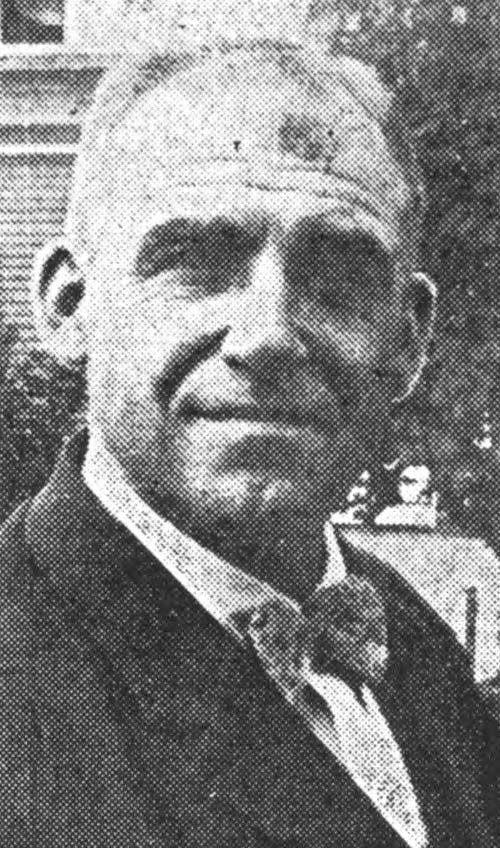

BARRINGTON — Police Chief Albert Pearson Jr. knew he was about to cross a line that Sunday morning as he prepared to break into a house in a residential neighborhood.

“I hesitated about going in,” Pearson said later, “as without a search warrant my status was that of an ordinary trespasser. But I didn’t like to miss the chance to solve the mystery.”

Al was the type of man to do what it took to achieve just ends, even if the means were a little shaky.

This was 1927, and people in this rural town had been talking about “the mystery house” on New Meadow Road for months. Neighbors had seen strange men in cars frequenting the small cottage. Late at night, the house and its nearby barn were brightly lit. Pearson knew that the residents, “Mr. and Mrs. A. Walters,” were up to no good.

But, when Deputy Chief Benjamin Bosworth came to him that Sunday morning with evidence that the Walterses were out of town for the weekend, Al decided that it was time for a closer look.

“No one was in sight,” he later recalled. “We peered through the windows, but nothing unusual appeared.”

That didn’t stop him from going around back, unlocking the door and walking in.

“We didn’t attempt to make any intensive search but merely glanced around,” he said.

They didn’t find anything suspicious, let alone incriminating, went back out, locked the door and went to look in the windows of the barn.

Al spotted something very suspicious there: a Chrysler sedan with no license plates.

For the second time that Sunday morning, Al broke into a building without a warrant.

He lifted the hood of the car and found that the identifying number on the engine had been filed off. And the car was full of burglar’s tools: bolt cutters, jimmies and other ways of breaking into things.

Officers set up watch in the woods behind the house. The next day, Monday, Sept. 19, 1927, “Mr. and Mrs. Walters” returned home.

It was time to knock on their door and ask the couple just what they were up to in Barrington.

Factory work and the Navy law on Al Pearson’s path to being a lawman

Albert Pearson Jr. was born in 1899 in Central Falls, the son of an English immigrant who had moved to the Blackstone Valley to find work in the mills.

When Al was about 15, Albert Sr. moved his family from Central Falls to the Bay Spring village of Barrington, settling on Lake Avenue, about a quarter mile from where Herbert Johnson called Pheling’s shack his home. Teenager Al must have known the 3-year-old Black boy who lived at the other end of his street. He must have heard about the boy’s chaotic family life, the lack of food and clothing, the bouncing around from one relative to another, the stints in the Sockanosset School and the state orphanage.

As a young man, Al worked with his father in a jewelry factory and he served in the Navy, at sea during World War I, and, in 1920 and 1921, at the Naval Training Station in Newport.

While on leave from Newport one day, he took the train up to Woonsocket to watch a movie.

He became smitten with a girl who worked in the theater, Edwina Thibeault, who also worked in a cotton mill. She had been born Marie Corona Edwina Thibault on Nov. 11, 1900, in Wickham, Drummond County, Quebec.

That day in the theater, Al cut quite the dashing figure — 5 foot 7, with a trim build, brown hair, brown eyes and a ruddy complexion. Add in the Navy uniform, and Edwina couldn’t resist the handsome sailor.

In April 1921, two months before his discharge from the Navy, Al and Edwina were married at the Baptist Church in Warren. In February 1922, their first daughter, Pearl, was born, to be followed in the next few years by a sister and two brothers.

As his family grew, Al got into police work, becoming Barrington’s chief on March 14, 1927, about the same time that “Mr. and Mrs. A. Walters” had moved into the small cottage among tall pines in a remote corner of town tucked near the Massachusetts line.

Al Pearson returns to New Meadow Road

When Al and Deputy Chief Bosworth broke into the New Meadow Road house on Sunday, they were alone by design, given the clandestine nature of their foray.

But, the following day, they brought a crowd, including a swarm of state troopers.

When they opened the front door, they interrupted a woman in the middle of sweeping the floor.

She ordered them to shut the door. “I don’t want my house full of flies!”

Al immediately recognized the blue-eyed blonde with a telltale birthmark above her right eye.

They had met two years earlier when he was investigating an illegal still that had blown up in a building on another property where she had lived. She had made quite the impression on Al back then: smoking a cigarette while lounging on a couch wearing not much besides silk stockings, crossing one shapely leg over the other, seeming to delight in the discomfort she caused in the police officers who had come to investigate the explosion.

Al had come to know her as the wife of George Savage, the dapper head of the “Pawtucket gang,” the most notorious band of hijackers, safecrackers and robbers in Rhode Island.

“Well, well,” said Al, “if it isn’t my old friend Loretta!”

She looked at him with scorn but said nothing.

“Where’s George, Loretta? he asked.

She kept sweeping without saying a word.

Al and a state police sergeant raced up the stairs to the second floor, guns drawn. They found only a room someone had left in a hurry: a lit cigarette was burning on a table, and the window had been left open.

A search of the property turned up much to connect George and Loretta Savage to the Pawtucket gang and a string of recent crimes, including the spectacular 1925 robbery of the Pawtucket Post Office, when four gangsters tied up two night watchmen, used blowtorches to crack the safe and made off with $262,000 worth of stamps and other items, which would be worth $4.4 million in 2023.

The Barrington raid marked the beginning of the end of Savage’s gang and the rise of Al Pearson’s career as a lawman, one that would peak a few years later with an odd move: pleading for the life of a convicted murderer.

Chapter 6: Herbert Johnson on trial for murder

SCHOHARIE, N.Y. — Herbert could hear a commotion outside his jail cell.

Men were hurrying to do something. It was less than a month after the armed posse had captured him in the woods outside the village. Less than a month after the villagers, shouting “an eye for an eye,” threatened to lynch him.

These were not the noises of the normal, daily jail routine. Something was up.

Several men made their way inside Herbert’s cell.

“Come on!” they barked at Herbert. “Time to go!”

Herbert found himself in handcuffs, being led out to a car by the sheriff and a deputy.

Herbert recognized the road — from Schoharie to Schenectady — from the night they took him to see Sheriff Steadman in the hospital.

But this time, they didn’t take him to the hospital. They brought him to the Schenectady County Jail.

Undersheriff Frank L. Lescault, who had assumed Steadman’s duties after the sheriff’s death, knew Schoharie County’s jail was understaffed. He knew people in the village were still seething. He knew he might not be able to stave off another lynch mob.

Herbert would be safer in Schenectady County.

He would be housed there until his trial.

Although Schoharie was too dangerous to jail Herbert, his trial proceeds there

Although his jailers thought it wise to move Herbert to Schenectady County, his court-appointed defense lawyer, Francis L. Smith, never sought to move the actual trial out of Schoharie County. Herbert would be tried in the same building where Sheriff Steadman was shot, in a courtroom one floor above the sheriff’s office.

Herbert’s jury would be drawn from the same pool of registered voters who'd elected Steadman as their sheriff.

That pool might include members of the posse that had hunted Herbert down. Or of the mob that had threatened to lynch him right outside the same courthouse.

Could anyone in the small county not have heard about the case? Could Herbert get a fair trial in Schoharie?

Life in Schoharie stops as Herbert’s trial starts

Anticipating that many in Schoharie County had already decided Herbert was guilty, Judge Pierce H. Russell ordered an extra 75 prospective jurors be called, on top of the 36 that normally were called for criminal cases. That should be enough to seat an impartial jury.

On Tuesday, Jan. 6, 1931, the trial opened with the prosecutor, District Attorney Sharon J. Mauhs, quizzing each juror carefully, especially trying to detect those who opposed the death penalty and might vote for an acquittal for that reason only.

Defense lawyer Smith was equally diligent in trying to root out jurors who would be biased against his 19-year-old client because he was Black.

After going through the more than 100 prospective jurors, only 10 of the 12 needed were selected. Judge Russell ordered that another 20 be called.

That additional pool only yielded a single qualified juror, bringing the panel up to 11, so Judge Russell ordered sheriffs to gather the first 15 men they could find, in the courthouse or on the streets, to be prospective jurors.

Finally, on Thursday morning, 12 men – nine farmers, a carpenter, an oil truck driver and a salesman for a nursery – were seated for the jury. Their average age was 52. They were all white.

As was the judge and the prosecutor and Herbert’s own lawyer.

The jurors would be sequestered next door to the courthouse, in the Parrott House hotel, for the week-long trial.

Prosecution opens trial: 'Herbert Johnson … had murder in his heart'

In his opening statement, prosecutor Mauhs previewed the case he would present against Herbert:

“We are going to show you, gentlemen, beyond any reasonable doubt, beyond any question, that Herbert Johnson, on the morning of July 16, 1930, had murder in his heart.”

Defense lawyer Smith conceded that Herbert was guilty of homicide, that it was his gun that had killed Sheriff Steadman. But, Smith contended, Herbert had committed the lesser crime of manslaughter, not an intentional murder.

“The defendant did not have any intention at any time of shooting the sheriff,” he told the jury. “He was using his gun at that time to try to escape.”

Smith said that Herbert, with his chaotic upbringing, was incapable of the premeditation needed for the slaying to be considered murder.

“We will … show you as to his mental condition. You have a right to observe him yourself,” Smith said. “We will show you that he is infantile, like a child. Impulsive.” He lacked the ability to plan ahead to commit a crime.

Smith pointed out that Herbert had every chance to shoot the sheriff before Steadman tried to grab the gun, and that he could have shot Deputy Sheriff Lynk, too.

“In fact, he wasn’t there to shoot his way out,” Smith said. “The things that he did were very foolish.”

Deputy sheriff testifies: 'I’ll kill you both'

Deputy Sheriff Lynk testified that, in the sheriff’s office on the day of the shooting, Herbert had told the two lawmen, “Stick ’em up the both of you, or I’ll kill you both.”

When Smith cross-examined Lynk, the defense lawyer pointed out that the deputy had not mentioned the damning phrase “or I’ll kill you both” when he gave a sworn affidavit the day after the shooting.

Lynk conceded that “or I’ll kill you both” was missing from his statement.

“And you think that the district attorney refused to put it in the affidavit, or something?” Smith asked Lynk.

“No, I don’t accuse anybody of it.”

But Henry Walker, the hitchhiker Herbert had picked up in Pennsylvania, supported Lynk.

“I heard someone say, ’Stick ’em up or I’ll kill both of you,’” Walker testified, “and I turned around and I saw Johnson with a gun, waving it in the room.”

Herbert takes the stand: 'I wanted to get out of that office'

Herbert took the stand around 2 p.m., Friday, Jan. 9, and the tiny village of Schoharie came to a halt. Some 2,000 people called the village home. That afternoon, nearly 700 of them jammed into the courtroom to hear the famous prisoner. The room, including a balcony gallery, was only built to hold 400. Once in the courtroom, people couldn’t move.

Smith started by walking Herbert through his life’s story, of being bounced from his mother to his father to an aunt and other family members, of the Sockanosset reform school and the State Home & School for orphans.

Smith asked him about the Fall River birth certificate that said he was white and that his name was Matthew Taft.

What no one in that courtroom knew was that the birth certificate was wrong. A clerical error had produced the copy that showed “Matthew Taft” was white. But Herbert’s true birth certificate, still on file in Fall River under the name “Matthew Taft,” clearly lists his race as “Colored.”

And what wasn’t mentioned in court: When Herbert was 3 years old, his mother married Pheling, and Herbert never knew any other father.

Prosecutor Mauhs would make much of these discrepancies.

But first, Herbert described the fateful instant in the sheriff’s office: “When the sheriff came towards me, he came out with both of his hands and made a grab for my right hand that held the gun; when his hands touched my hand, the gun was discharged.”

The crowd burst into laughter.

“Order! Order!” Judge Russell bellowed, banging his gavel repeatedly until the gallery quieted down.

“Did you intend to shoot the sheriff?” Smith asked his client.

“I didn’t have no intentions at all,” Herbert testified in a slow, firm and distinct voice.

“What did you aim the pistol at him for?” his lawyer asked.

“I wanted to get out of that office.”

Mental-health expert testifies for the defense: 'He had very poor planning ability'

The defense called Dr. Clinton P. McCord, whom the court qualified as an expert on “mental disease and defects.” McCord had tested Herbert a month earlier, when he was in the Schenectady jail.

The doctor found Herbert had an IQ of 84 and a mental age of just younger than 13.

“Our examination revealed the fact that this boy was neither insane nor mentally defective,” the doctor testified.

“How would you designate the defendant emotionally?” Smith asked.

“Very passive. His reactions very slow, not very much foresight, very primitive in emotional reactions, very easily led to acting on impulses of the moment, not thinking through a situation,” the doctor said. “Our tests of performance showed that he had very poor planning ability.”

Prosecutor Mauhs got to the heart of the matter: “Does the defendant, Johnson, Dr. McCord, from your examinations, know the difference between right and wrong?”

“He does.”

McCord had not helped Herbert’s case.

The defense abruptly rested.

That night, back in the Schoharie County Jail, next to the courthouse, Herbert played a few songs on the harmonica, recalling his days in the Sockanosset School band. Among those enjoying the nightly entertainment was Jesse Millspaw. A 33-year-old native of Missouri, Millspaw was a clerk at the post office in Cobleskill village. He also was a deputy sheriff, which normally was not a full-time job. During the trial, Millspaw sat next to Herbert in the courtroom, ready to restrain him if he tried to flee, or protect him if the crowd got out of hand.

The defense tells the jury it’s manslaughter

On Tuesday morning, Jan. 13, the lawyers began their closing arguments, with the defense going first.

Smith tried to defang the issue of the erroneous birth certificate.

“The defendant sits there. There is no question over his identity,” Smith told the jurors. “Any emphasis put upon who he is, or what he is, other than what relates to the crime here, is for the purpose of prejudicing you against that defendant.”

Smith made his argument that Herbert should be convicted of manslaughter, not murder. “What we claim here is that there was no premeditation or deliberation in the act which caused the sheriff’s death at Schoharie,” Smith said. “I am not asking for mercy; I am asking for plain justice.”

Who’s telling the truth?

Mauhs asked the jurors whom they believed: Lynk, who said Herbert had threatened to kill the sheriff and the deputy minutes before the fatal shot was fired, or Herbert, who'd said that he made no such threat and that the shooting was accidental.

“Now, gentlemen, there is a fundamental rule of law … that if you find a witness upon the stand has proved himself false in one thing, then you can disregard his entire testimony, and you can assume that he has been false in everything.”

And then Mauhs named that one false thing that should invalidate all of Herbert’s testimony: simply that Herbert had presented a birth certificate that said he was white.

Mauhs described Herbert bluntly: “Johnson has led a life of crime,” the prosecutor said. “You have a cool, intelligent, vicious, selfish criminal, who shot down an officer of this county in cold blood. That is what you have got here; that is the unvarnished truth.”

Mauhs said the jury had only one way to get justice for Henry Steadman:

“The die is cast. A terrible doom has settled down over this defendant. It remains only for you men to come back into this court and bring in your verdict, ‘Guilty! Guilty! Guilty! Herbert Johnson! Guilty of murder in the first degree!’”

The jury asks the judge for help

The jury began its deliberations at 4:55 p.m.

They would return at 8:27 p.m., but only to ask the judge to clarify something:

Does the fact that Herbert waited a minute, maybe two, without shooting prove premeditation or does the hesitation disprove it?

“Well, gentlemen of the jury,” Judge Russell said, “that is entirely a question for you to determine.”

The jury went back to continue deliberating at 8:35 p.m.

They took their first, and only, vote of the evening.

They were back 12 minutes later, at 8:47.

“Gentlemen, have you agreed upon a verdict?” asked the court clerk.

“We have.”

“How do you find?” asked the clerk.

Jury foreman Grantier Hutton reported:

“We find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree.”

Herbert barely moved. Nothing gave away his thoughts. He looked straight ahead.

Smith asked the judge to set aside the verdict. He said there wasn’t enough evidence for a murder conviction.

“Motion denied.” The judge set sentencing for Friday morning. But that would only be a formality. The mandatory sentence for first-degree murder was death.

Deputy sheriffs and state troopers led Herbert out to his jail cell.

And the floodgates of emotion opened. Herbert sobbed uncontrollably.

After a while, his jailers calmed him down, and Herbert wrote a letter to his mother.

He refused all food that night. He did not play his harmonica.

The judge sentences Herbert to death

“We have now arrived at a time that is very sad for you and very unpleasant for me,” Judge Russell told Herbert Friday morning.

The judge praised the lawyer he had appointed to represent Herbert. “In the trial of this case you have been defended by a lawyer of marked ability; he gave to your cause unstinted effort, time and study.”

And he praised the process.

“I feel that you have had a fair trial.”

Judge Russell continued:

“The span of life from the cradle to the grave is short. By your act, you have shortened not only the life of Henry Steadman, but you have shortened your own,” he said.

“There might be some consolation in the fact that all mortals now treading this earth will shortly appear before their Maker.”

Then, Russell fulfilled the duty dictated to him by statute:

“The sentence and judgment of this court is that you, Herbert Johnson, be removed to the Sing Sing State Prison at Ossining, to be kept in solitary confinement until the week beginning March 1, 1931, and that upon some day within the week so appointed, you, Herbert Johnson, be put to death.”

Less than an hour later, the sheriff and three deputies had Herbert in a car on the way to Sing Sing.

Chapter 7: Al Pearson pleads for the life of a man sentenced to die

BARRINGTON — Police Matron Angelina M. Cirillo didn’t like it when people in town talked about her relationship with Police Chief Albert Pearson.

As spring turned to summer in 1931, she reached a breaking point and decided to resign from the police department.

But first, she owed Al an explanation.

“They say I am too young and pretty,” Angie, 26, told Al, 31. “They” were the Town Council.

Truth is, though, it was more than just the councilmen who had been talking about “Al and Angie.”

Born Angelina Jiacovelli on Oct. 12, 1904, in Johnston to Italian immigrants, Angie, her parents and her four brothers and sisters moved to Barrington before Angie started school. They settled in the burgeoning immigrant community clustered around brick-making factories on Barrington’s Maple Avenue, where Italian was spoken in most homes.

Al’s fame had been growing since he helped put away the Pawtucket Gang, and, in the closing years of the 1920s, the sight of the celebrity lawman and the raven-haired thread-mill worker driving around Barrington and Warren in the chief’s car became familiar.

Al got the Town Council to appoint Angie as the police matron. He also got Angie’s husband, Frank Willard Cirillo, owner of Willard’s Beauty Salon on Westminster Street in Providence, an appointment to the position of police constable.

Al had stuck by Angie “through thick and thin,” as she put it. He listened about the trouble she had with her mother-in-law. He listened to her troubles having a baby. He listened when her husband stopped listening.

Al was a frequent guest at the Cirillos’ house.

He invited Angie to his own house to enjoy meals cooked by his wife, Edwina.

On at least one occasion, the Pearsons' eldest daughter, Pearl Edwina Pearson, reported seeing her father with his arm around Angie’s waist.

People were talking.

In June 1931, Angie told Al that she had mentioned resigning to Councilman John W. Parker. “Councilman Parker told me … that such a step would only make it worse.”

But Angie was tired of the whispers and the conversations that stopped when she entered the room. “I think it will be better for me to leave.”

On June 18, after about a year and a half as matron, she mailed her resignation to the Town Council.

Al makes an unusual request

The timing could not have been more awkward for Al. On July 7, he would be going before the Town Council with an unusual request.

Herbert’s execution had been postponed from March to give New York’s top court time to consider – and reject – his appeal.

Now, his only hope was that Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York’s governor, would intercede.

And, in early July, a glimmer of hope appeared. Roosevelt scheduled a clemency hearing for July 16 to consider whether to delay the execution, now scheduled for a week later.

Roy L. McLaughlin, who had been superintendent of the Sockanosset School when Herbert was there, was organizing a group of Rhode Islanders who had known Herbert when he was younger to attend the hearing on his behalf.

Al wanted to go and plead for the life of the young boy who had lived in the shack down the road from him in Bay Spring when Al was a teen, plead for the young Black man who, as several said, “never had a chance.”

On July 7, Al appeared before the council, presenting a plan to show Roosevelt photos of the shack Herbert had lived in as a young boy. Al would bring 25 petitions seeking clemency for Herbert, signed by residents of Barrington, which would be in addition to a statewide petition signed by 300.

People in Barrington had raised money to pay for the trip to Albany.

The town of 5,162 residents — six of them Black — was rallying around the young Black man who had called Barrington home for a few years of his chaotic life.

Al meets with FDR

On July 16, Al sat in the governor’s office in Albany next to Roy McLaughlin; Warren C. Glanville, who had been Herbert’s Sunday school teacher at Sockanosst; Bessie A. Whalen, a social worker there; and James M. Stockett, a Black lawyer with the Providence NAACP. The Rhode Island group was joined by a representative of the Albany Inter-Racial Council.

Al told the governor that he was there not only as a police officer, but as a friend who'd known Herbert as a child, who knew of his pitiful home environment.

“His surroundings were most unfortunate, but he never was convicted of any crime, except for theft of a bicycle, which he sold for $2,” Al told Roosevelt. “He is not a killer. I don’t believe he deliberately committed this murder. He was cornered and the gun went off.”

When his time came, McLaughlin leaned over Roosevelt’s desk. He spoke quietly, in a steady voice about the abysmal upbringing Herbert had endured.

“A picture of his one-room home was published on the front page of a booklet as a horrible example of the worst type of early environment,” McLaughlin said. He described Herbert as “the best-hearted kid” and called him “too good to be in a state correctional school.”

McLaughlin closed by relating a visit he had just paid to Sing Sing Prison: “I talked with him yesterday in the death house. He hasn’t changed a whit from the boy we knew.”

The NAACP’s Stockett emphasized that Herbert’s difficult upbringing had left him with the intellectual abilities of an 11-year-old. “It would be hard for a white boy of his mentality to make his way in the world,” he said. “It was doubly hard for a Negro.”

Roosevelt was moved. He ordered the state commissioner of mental hygiene to examine Herbert’s mental condition.

“I won’t let the execution proceed until I hear from the commissioner.”

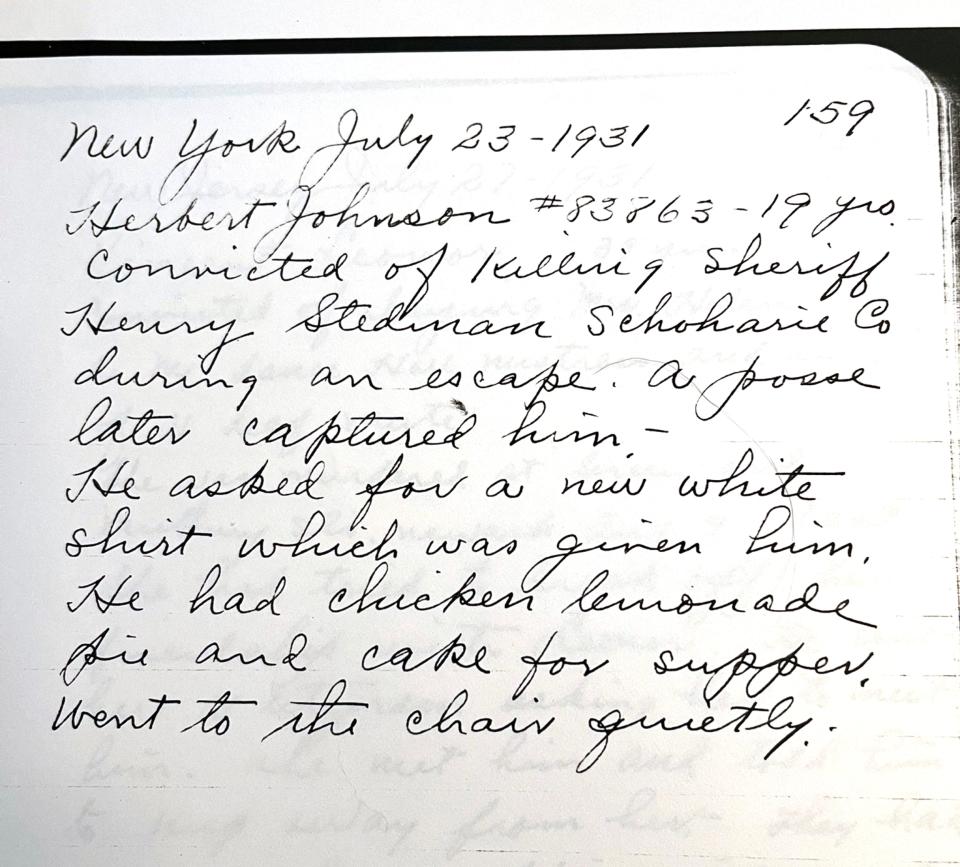

Chapter 9: Herbert Johnson orders his final meal

OSSINING, N.Y. — By the time Herbert Johnson woke up on Thursday, July 23, 1931, Gov. Franklin Roosevelt had not yet called Sing Sing to cancel the execution, so officials in the prison’s death house went about their usual preparations for an execution late that night.

The day before, an Associated Press reporter spoke with Roosevelt and asked about the mental hygiene commissioner’s report on Herbert’s mental condition.

“No insanity,” said the governor. “No mental disease.”

“Will you stop the execution?” asked the reporter.

Roosevelt declined to say.

Sometime on Thursday, Robert Greene Elliott made his way from his home in Queens, New York, up the Hudson River to Ossining. Elliott was “state electrician” of New York, the man who operated the electric chair at Sing Sing. The executioner.

That afternoon, Jesse Millspaw, the Schoharie deputy sheriff who had befriended Herbert while guarding and protecting him during the trial, set out from Schoharie toward Sing Sing, along with Leslie L. Shafer, another Schoharie lawman.

Some of those involved with Herbert’s appeal to Roosevelt worked throughout the afternoon to set up the phone call from the governor to the prison to at least delay the execution, if not cancel it.

In a long-standing tradition for condemned prisoners, Herbert was allowed to choose his final meal. Guards brought his order: chicken, mashed potatoes, rolls, ice cream and lemonade. One guard noted that he also had pie and cake.

The always-dapper Herbert asked for a new white shirt to wear that night, and prison officials gave him one.

“I lost my head,” Herbert told his guards. “I can’t understand how I could have killed the sheriff.”

Just before 11 p.m., Deputy Sheriff Millspaw and Leslie Shafer entered the death chamber, where Elliott had already tested the electric chair to make sure it was ready. Millspaw and Shafer were joined by prison officials and newspaper reporters.

The Rev. Anthony N. Peterson, a Presbyterian minister, walked “the last mile” with Herbert, the short distance from his cell in the death house to the death chamber itself.

The chamber, a bare, white room that housed the electric chair, was brightly lit. The room was stuffy in the July night.

Herbert quietly walked to the chair and sat down.

A guard attached an electrode to Herbert’s right leg. The electrode was a piece of sponge, dampened with salt water to conduct electricity better, attached to a metal plate connected to a wire that led to a nearby control panel.

Herbert pulled the right leg of his pants down after the guard was done. Another guard tightened leather straps that bound Herbert to the heavy wooden chair.

Elliott placed another electrode, inside a modified leather football helmet, on Herbert’s head. A guard placed a black leather mask over Herbert’s face, and tightened it to hold Herbert’s head against the headrest.

Herbert was asked if he had any last words.

He said nothing.

As Jesse Millspaw watched, Elliott stepped into a nearby alcove, from which he had a perfect view of the electric chair, to make sure everything was ready.

At 11:05 p.m., Elliott threw the switch that closed the circuit and sent 2,000 volts of alternating current tearing through Herbert’s body. Over the next two minutes, Elliott adjusted the dial, lowering the voltage and raising it back up, a measure to ensure that the process, while designed to be painless, would be effective.

Herbert Johnson died at 11:07 p.m.

Epilogue: What became of key figures in this series?

Al Pearson

Al did not return home from Albany the hero who had saved Herbert Johnson’s life.

And his relationship with Angie Cirillo continued to cause trouble.

The Town Council looked for any excuse to force Al out.

On April 5, 1932, Frank Cirillo filed for divorce from Angie, saying that she had “consorted” with other men. But the cause of their breakup may have had deeper roots.

Almost eight years earlier, on Dec. 7, 1924, the couple had welcomed their first-born and only child, a baby boy named after his father.

On Christmas Day, the child became ill with a liver condition common in newborns.

Four days later, baby Frank died at home. Angie would never have another child.

In August 1932, the town councilmen ramped up their campaign against Al. Over three weeks, they held three closed-door meetings.

First, they placed Al on probation and ordered him to report his whereabouts to them every hour he was on duty.

Then they suspended him.

Finally, on Aug. 22, after accusing him of mishandling money from fines, they fired him, even though they acknowledged that the charges against him couldn’t be proven. Just the mere fact that the charges were brought up at all indicated a morale problem in the police department caused by Al’s inattention to the job, the council said.

On Sept. 30, 1932, the judge signed Angie’s divorce from Frank.

That same day, Edwina filed for divorce from Al. And the couple’s eldest child, daughter Pearl, decided she would never speak to her father again.

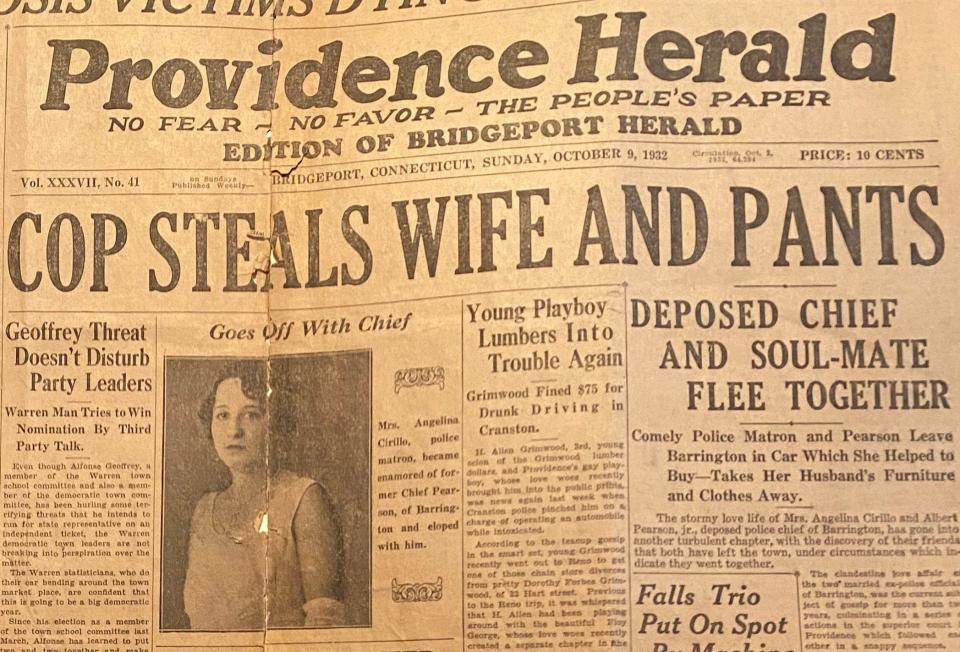

With Al out of work and Angie estranged from her husband, Al and Angie hit the road together, attracting newspaper headlines. “Cop steals wife and pants” screamed an all-caps headline in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that October, detailing how, when Angie left Frank Cirillo with Al, she took Frank’s furniture and his clothes.

The same month, Angie mailed her ex-husband a letter from Oklahoma City.

She addressed him, “Dear Hon,” and then noted, “It seems ages since I’ve used the word.”

She hinted that his family, especially his mother, had turned him against her. “Your folks in Bristol were never really crazy about me.”

She blamed him for wronging her, but never specified how. “You have brought me more disgrace than all the Pearsons put together,” she wrote. “I admire Al for sticking to me through thick and thin, and I hope some day I can repay him back.”

And she blamed her ex for the scandal involving Al and the Town Council. “Through your actions … he lost his $50.00 [a] week job.”

Angie closed the letter, “With love as ever.”

Ten years after the divorce filings, Al married Angie on May 15, 1943, at the Warren Baptist Church, the same place he had married Edwina 22 years earlier.

Edwina died in 1955 and was buried in Precious Blood Cemetery in Woonsocket.

Years after Edwina’s death, and some 30 years after the divorce drama began, Pearl reconciled with her father.

Al and Angie would be married for 41 years, until her death in 1984 at age 79.

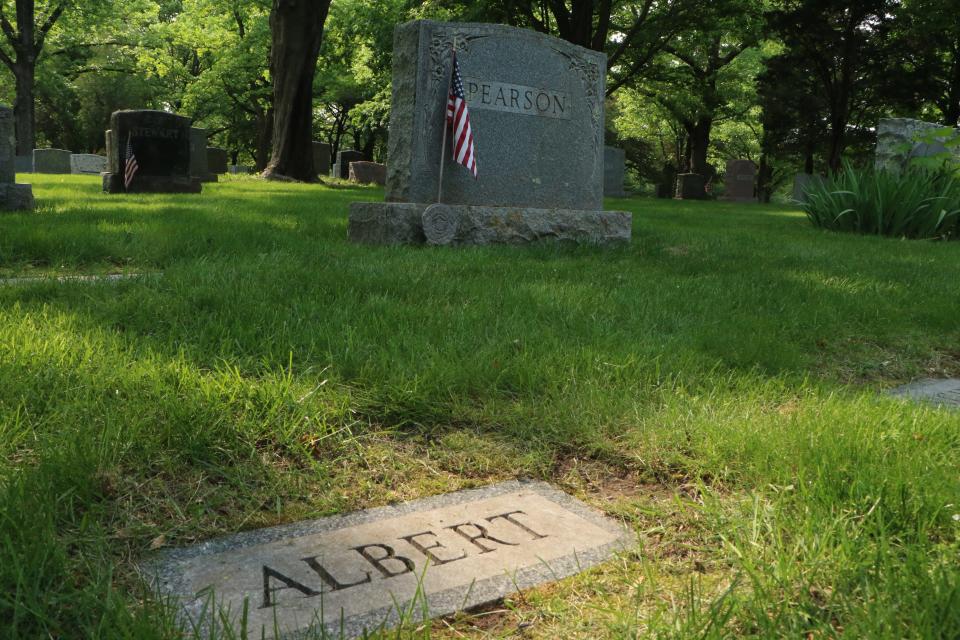

Al lived 10 more years, dying in 1994 at age 94, in the Rhode Island Veterans Home in Bristol. He was buried in Barrington’s Forest Chapel Cemetery, side-by-side with Angie.

Four years later, Al’s daughter Pearl had her mother exhumed from Precious Blood Cemetery. Pearl had Edwina reburied in the Pearson family plot in Barrington, head-to-foot with Al, forming a triangle with Angie for eternity.

Herbert Johnson

Herbert’s father, Pheling, had his son’s body shipped back to Rhode Island, completing the trip from Chicago Herbert had begun a year earlier.

Herbert’s funeral was held July 27, 1931, at M.R. Armstrong funeral parlors, 312½ Cranston St., Providence.

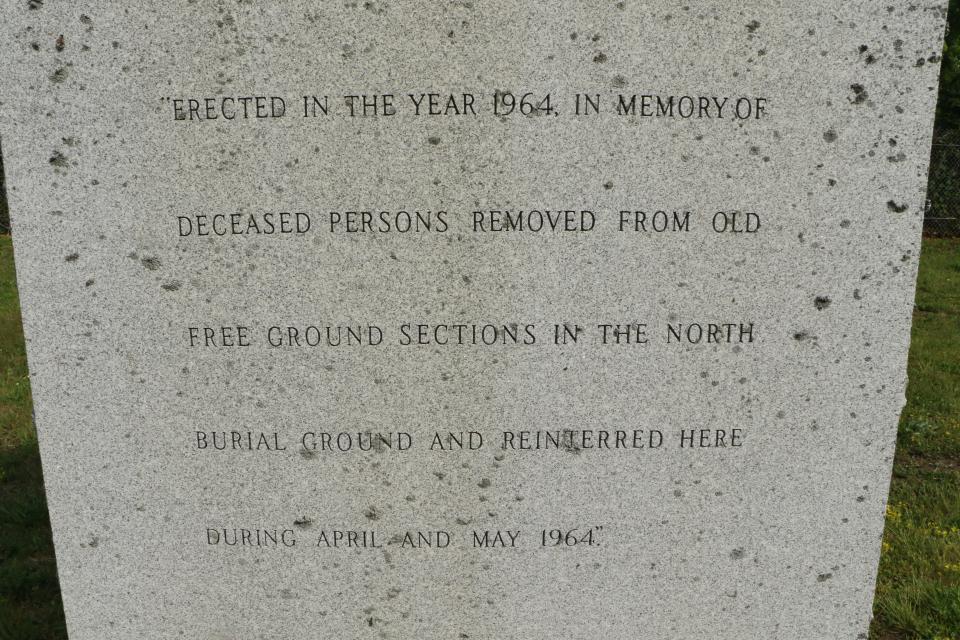

He was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the “free ground” section of the city’s North Burial Ground. His eternal rest would last three decades, until the state built Interstate 95 through part of the cemetery.

From March 16 to May 25, 1964, the state dug up 3,355 graves in the free ground section, relocating them to a new Potter’s Field, separated from the main part of the cemetery by the Moshassuck River and a line of trees. Potter’s Field is hemmed in by the North Main Street highway exit ramp.

Herbert was among more than 2,000 people reburied in unmarked mass graves.

Seven years after Herbert’s death, the Town of Barrington declared his father’s shack a health hazard. Despite 76-year-old Pheling’s plea to let him stay “in the home where I have lived nearly all my life,” the Town Council ordered it demolished in August 1938, removing the one place that Herbert had called home.

A month later, the Hurricane of 1938 tore through Bay Spring, remaking the landscape as it devastated the entire state.

Now an overgrown marsh, the land that Herbert had headed East through Schoharie County to get from his father is barely dry land at all.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Death sentence for Black teen from Barrington now seen as legal lynching