Black voters over-represented in new DeSantis unit's election crimes arrests

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The vast majority of Florida residents who have been arrested by Gov. Ron DeSantis' new election crimes unit are Black, a review by The Palm Beach Post has found.

That 15 of the 19 arrested so far are Black confirms for DeSantis' political opponents and for voting rights advocates that the new unit is functioning precisely as intended — not as a bulwark against nearly non-existent election fraud but as a means of suppressing and intimidating Black voters who are unlikely to support DeSantis or other Florida Republican Party office-seekers, the newspaper found.

Read more: Local Black clergy, political and social group leaders blast DeSantis' redistricting plans

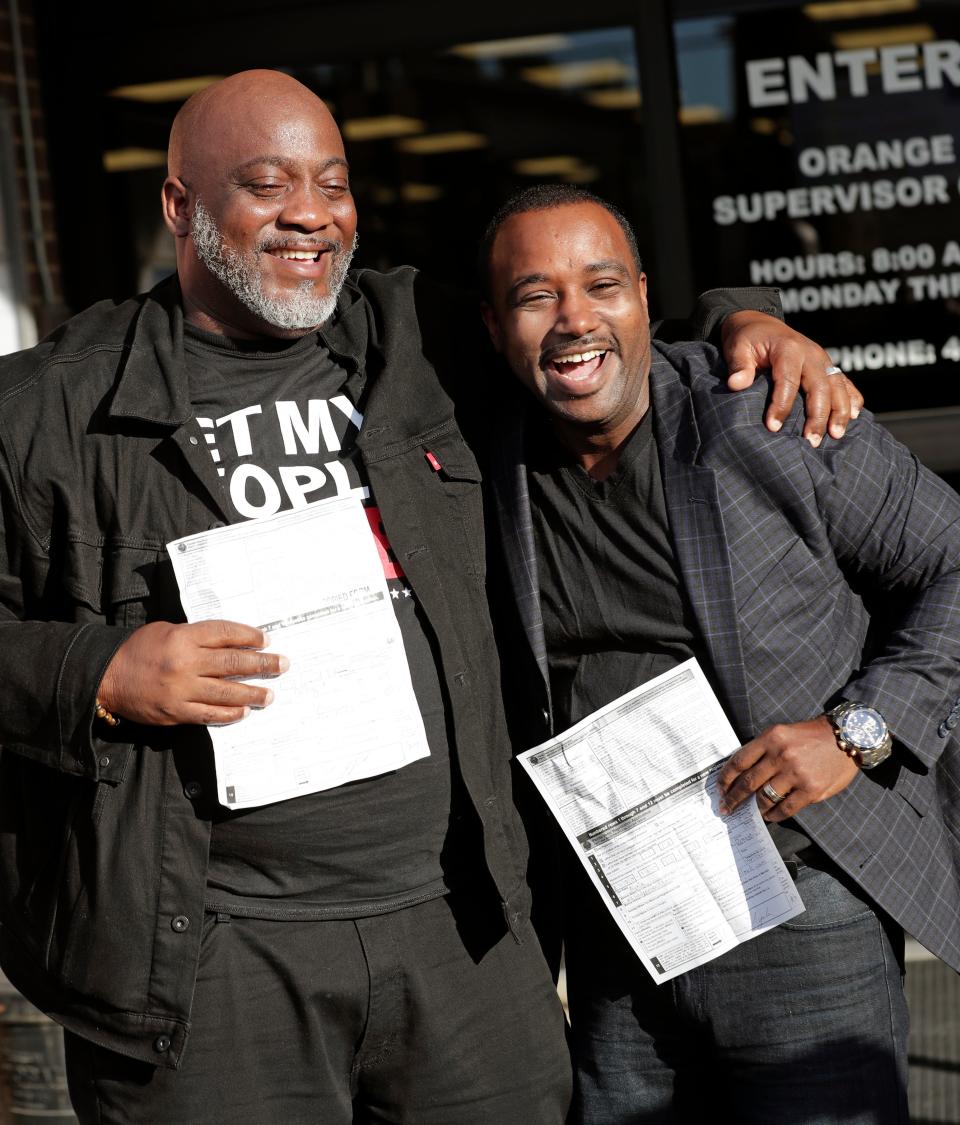

"I don’t feel like I did anything wrong": Florida felon voters may have law on their side

"It was always obvious that this would be used to target and strike fear in Black voters, and this is coming to fruition," said state Sen. Bobby Powell, a West Palm Beach Democrat who argued against establishment of DeSantis' unit, which is called the Florida Office of Election Crimes and Security.

Powell and others see the election crimes unit as part of a national wave of voter suppression efforts aimed at tipping the political scales in favor of Republicans by limiting the influence of Black voters, the Democratic Party's most supportive voting bloc.

The governor's office has not responded to multiple requests for comment about the work of the election crimes unit, including several made before Hurricane Ian made landfall.

During a press conference in August to announce election crimes arrests, DeSantis did lay out his rationale for the formation of the unit.

"The purpose of that was to investigate things like voter fraud and other violations of election law," he said. "What ends up happening is you will see some examples — and granted, in 2020 in Florida, not on a grand scale — but you would see examples, and nothing would get prosecuted. Nothing would end up happening. Well, that's just going to beget more of it."

On multiple fronts, the election crimes unit is a political winner for DeSantis, who is running for re-election as governor and is widely thought to be a potential candidate for president in 2024.

Creating the law-enforcement unit capitalizes on anger in GOP circles — fed by lies from former President Donald Trump about his defeat in 2020 — that alleged election fraud is harming their political fortunes.

In fact, in Florida and across the country, election fraud is rare.

Two years ago, DeSantis himself praised how well the presidential election was conducted in the Sunshine State.

"The way Florida did it, I think, inspires confidence," he said. "I think that's how elections should be run."

Less than two years later, however, with Trump and other Republicans banging the drum that elections were being "rigged" in a way that benefits Democrats, DeSantis established the election crimes office.

'Another form of voter suppression'

Its establishment appeases those GOP voters who believe election fraud to be a problem, and, if its early results hold true over time, the unit will chip away at the electorate in Florida in ways that benefit DeSantis and other Republicans.

Critics, however, see the unit as a vehicle for frightening some wary Black voters away from the polls.

"It's 'Try it, we got you,'" said Patrick Franklin, president and chief executive officer of the Urban League of Palm Beach County. "That's definitely aimed at African Americans. It's another form of voter suppression."

Republican leaders in the Sunshine State have, in recent years, backed various changes to make it more difficult to vote, changes that tend to have a disproportionate impact on Black voters and poor voters.

DeSantis has signed legislation that limits the location of ballot drop boxes to the office of election supervisors, and voters can only use them during voting hours. That move makes it harder for people who don't have the flexibility of voting during the day to cast a ballot.

Voter registration groups face larger fines if they don't submit voter applications within 14 days, increasing financial risks for small-budget groups like churches or community organizations working to register new voters.

Vote-by-mail ballots must now be requested every two years instead of every four years, which could pose burdens for people without access to a car or a computer.

And then there is the new election crimes unit.

In a blistering, 288-page ruling on challenges to the state's new voting laws, U.S. District Court Judge Mark E. Walker found that, "Florida has repeatedly, recently, and persistently acted to deny Black Floridians access to the franchise."

The judge wrote that: "For the past 20 years, the majority in the Florida Legislature has attacked the voting rights of its Black constituents. They have done so not as, in the words of Dr. King, 'vicious racists, with [the] governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification,' but as part of a cynical effort to suppress turnout

among their opponents’ supporters."

Walker struck down changes to Florida's voting laws, but his ruling was overturned by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, allowing the state to move forward with the new restrictions.

When it comes to voting rights, Florida has long, sordid, sometimes painful history

In many ways, history is repeating itself in Florida when it comes to voting rights.

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed by Congress in February 1869 and ratified by the states a year later, prohibits the federal government or any state from denying a citizen the right to vote based on their race.

But with millions of former slaves casting ballots, re-shaping — and in some instances, re-coloring — the nation's political landscape, white Southerners turned to several work-arounds of the 15th Amendment.

They used racial violence, beating and killing untold numbers of Black Americans who sought to vote.

They imposed poll taxes that disproportionately affected newly freed but still desperately poor Black Americans. They passed "grandfather" clauses that limited voting to those whose grandfathers could vote, a tactic sure to exclude Black citizens whose grandparents had been enslaved. And they tweaked felon voting rights restrictions with a new goal: keeping Black citizens away from the polls.

"Several Southern states tailored their disenfranchisement laws in order to bar Black male voters, targeting those offenses believed to be committed most frequently by the Black population," states a report from The Sentencing Project, an education and advocacy group set up to reduce incarceration in the U.S. "For example, party leaders in Mississippi called for disenfranchisement for offenses such as burglary, theft, and arson, but not for robbery or murder."

The report notes that "the author of Alabama’s disenfranchisement provision 'estimated the crime of wife-beating alone would disqualify sixty percent of the Negroes.'"

Over time, explicit poll taxes and grandfather clauses were struck down by legal rulings. But, with a federal judiciary that's far more conservative today than the ones that did away with poll taxes and grandfather clauses, felon disenfranchisement has endured despite its history and despite its disproportionate impact on Black citizens.

And, notwithstanding the protestations of those who argue that felon disenfranchisement is a color-blind punishment, its disparate impacts are clear.

"Black Americans of voting age are nearly four times as likely to lose their voting rights than the rest of the adult population, with one of every 16 Black adults disenfranchised nationally," The Sentencing Project found.

As of 2020, Florida was one of seven states where more than one in seven Black adults were disenfranchised. Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Virginia and one state outside of the South, Wyoming, were the others.

"Whether or not felony disenfranchisement laws today are intended to reduce the political clout of communities of color, this is their undeniable effect," The Sentencing Project found.

Black Floridians disproportionately hurt by felon disenfranchisement

The root of that disproportionate impact lies in the nature of who is arrested, charged and convicted of felonies.

There is no statewide database of Floridians who have been released from prison after serving time for a felony conviction. That makes it impossible to say with certainty that a law barring felons from voting is, essentially, a law targeting Black people.

But Florida's prison population, made up entirely of felons, offers some clue to just how over-represented Black people are likely to be among those who have been released after serving time for a felony.

Despite the fact that Black residents account for only 17% of Florida's population, there are more Black inmates than white inmates in the state's prison system, according to 2021 figures from the Florida Department of Corrections.

Black inmates account for 47.6% of the state's prison population. White inmates account for 39.4% of the prison population, despite the fact that white residents account for nearly 77% of the state's overall population.

Put another way, the percentage of Black inmates in Florida's state prisons is nearly three times as high as the percentage of Blacks in the overall state population. Meanwhile, the percentage of white inmates in Florida's state prisons is just over half of the percentage of whites in the overall state population.

Just as it can be deduced who makes up the bulk of Florida's felon population, the interplay of race and voting patterns is also clear.

The Pew Research Center found that 76% of Black Floridians are Democrats or lean Democratic, an affiliation grounded in the view that Democrats are more committed to protecting their civil rights and to pursuing economic policies that address income and job disparities.

National exit polling conducted after presidential elections has found that Black support for the Democratic Party nominee often approaches or exceeds 90 percent.

Intended or not, the felon disenfranchisement formula goes like this: Felon disenfranchisement disproportionately impacts Black residents; Black disenfranchisement equals fewer votes for Democrats; fewer votes for Democrats equals Republican victories.

In Florida, a few votes can mean the difference between winning and losing a gubernatorial race.

DeSantis knows that better than most.

He won election in 2018, defeating his Democratic opponent, Andrew Gillum, by fewer than 33,000 votes out of more than 8.2 million cast.

DeSantis' predecessor, Rick Scott, won similarly tight elections, squeaking through in his first race for governor by a 62,000-vote margin out of 5.4 million ballots cast and then getting re-elected by a 64,000-vote margin out of about 6 million ballots cast.

The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, established to end what it sees as discrimination against and disenfranchisement of people with felony convictions, estimates that about 1.6 million Floridians are ineligible to vote because of previous felony convictions.

"We're going to continue to see these suppression efforts because there's the potential of millions of people voting if we just get out of the way," Franklin said.

Voter amendment runs into barriers

Floridians tried to drive a stake through the heart of felon disenfranchisement.

In 2018, Florida voters approved Amendment 4, which restored the voting rights of people with felony convictions after they completed all of the terms of their sentence, including probation and parole. The amendment excluded felons convicted of sex crimes or murder.

Amendment 4 was passed by a large majority, getting nearly 65% of the vote.

Voting rights advocates rejoiced. But their joy was short-lived.

Florida's Republican Secretary of State, Ken Detzner, said he needed "direction" from the Republican-controlled Legislature to determine how the amendment was to be implemented.

Republicans offered that direction in the form of Senate Bill 7066, which stated that all terms and conditions of a sentence included the paying of all fines and fees associated with a felon's conviction. DeSantis signed the bill into law.

Democrats and voting rights advocates filed suit, arguing that requiring felons to pay all fees and fines associated with their conviction before they could regain the right to vote amounted to a new type of poll tax — pay up, or you still can't vote.

Many felons, voting rights advocates argued, couldn't afford to pay the fines and fees, and some couldn't even find out how much they still owed.

Some prominent Americans like basketball star LeBron James and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg paid the fines of some felons, but the financial barrier has still kept others from becoming eligible to vote.

Legal and voting rights advocates pressed their case against SB 7066, but it withstood legal challenges, and what had been thought to be a clarion call to restore voting rights to felons in one of the largest, most politically important states in the country withered to a peep.

"Amendment 4 is meant to restore voting rights to most people with felony convictions and is considered to be one of the largest expansions of voting rights in our nation’s history and a remedy to Florida’s racially discriminatory felony disenfranchisement system," Leah Aden, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund's deputy director for litigation, wrote in a statement to The Post. "Under SB 7066, Florida erects a system that makes it impossible, if not very difficult, to know who is eligible to register and vote in Florida."

'She served her debt to society'

Indeed, confusion has reigned since SB 7066's passage.

A group of legal and voting rights organizations produced a primer in August to tell eligible Florida felons how to get their voting rights restored. It's 15 pages long.

Passage of Amendment 4 received heavy, sustained news coverage. The successful court fight that led to its significant curtailment received much less coverage.

Some of the attorneys for those arrested for voting illegally said their clients did not know Amendment 4's reach had been limited by SB 7066. Many of those arrested sought and received voting registration cards.

One attorney, who did not want his client identified for fear of potential negative legal repercussions, said she got her voter registration card when she applied for a driver's license.

She even got an updated voter registration card after she got married.

"She served her debt to society," the attorney said. "She's remarried. She told them she was a felon. They told her that was OK. She thought her eligibility had been restored by Amendment 4."

Now, she — along with 18 others — is facing criminal prosecution for voting illegally. A 20th person is also being sought in connection with alleged voting crimes, according to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

SB 7066's author, state Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, tweeted that the intent of those seeking to register to vote should be assessed in making prosecutorial decisions.

"It was our intent that those ineligible would be granted some grace by the state if they registered without the intent to commit voter fraud," he tweeted. "Some of the individuals did check with SOEs (supervisors of elections) and believed they could register. #Intentmatters."

Those registering to vote in Florida must first attest that they are, in fact, eligible. Their application for a voter registration card is then sent to the state, which is supposed to verify the applicant's eligibility.

Neil Volz, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition's deputy director, said that's where the problem lies.

"The system is broken," Volz said.

In ruling against portions of SB 7066, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Hinkle found that, in some instances, the state could not say who is eligible to vote and who is ineligible.

“That the Director of the Division of Elections cannot say who is eligible makes clear that some voters also will not know,” Hinkle wrote.

As with other orders blocking election changes in Florida, Hinkle's order was overturned.

Still, Florida needs to be able to tell applicants if they are eligible to vote, Volz said.

"If I was a 13-year-old going into the DMV, they wouldn't give me a (driver's) license and then arrest me on the back end," he said.

Volz said that, if he had an opportunity to discuss this issue with DeSantis, he'd tell the governor: "Quickly focus on the front end of this election system and help us fix this."

But the governor's critics and some voting rights advocates have come to believe the governor has precisely the system he wants — one that allows for arrests and press conferences without regard to the impact on the people trying to put their lives back together.

Voter rights advocates: Arrests already 'chilling the participation of people'

Michael Gottlieb, a Democratic state legislator and attorney who represents one of those arrested for voting illegally, noted that DeSantis announced the elections arrests during a press conference in Broward County, a Democratic stronghold.

"That was absolutely done, in my opinion, to intimidate, to disenfranchise voters," Gottlieb said.

Aden said the Legal Defense Fund sees voter suppression designs in the arrests.

"We also warned the courts that these prosecutions would have another harmful impact – chilling the participation of people who would not want to risk registering and voting to get recaptured by Florida’s criminal system," she said.

Powell, the state senator, said that has already begun to happen.

"There were people who told me that they were concerned that they couldn't vote even though they had gotten their rights restored," Powell said. "They knew the governor was focused on this and that people could go to jail."

Even if those arrested are successful in fighting prosecution — many of their attorneys said they plan to focus on the fact that their clients were issued a voter registration card — the arrests have already altered their lives.

Roger Weeden, an Orlando attorney who represents one of those arrested, said his client has already lost his job.

"He worked for a lawn maintenance company," Weeden explained, adding that job opportunities for convicted felons are already scarce. "Just being a convicted felon is an impediment. You can't rent an apartment. Your credit is ruined."

Aden said her organization hopes Florida eventually remembers what voters supported in 2018.

"(NAACP Legal Defense Fund) wants the state to honor the will of millions of Floridians who supported Amendment 4 and second chances to participate in the political process for most people with felony convictions," she said. "We want state legislators to void SB 7066. We want the governor’s (unit) to stop these harmful prosecutions of people, who, based on the available evidence, are not intending to register and/or vote illegally."

Wayne Washington is a journalist covering West Palm Beach, Riviera Beach and race relations at The Palm Beach Post. You can reach him at wwashington@pbpost.com and follow him on Twitter @waynewashpbpost. Help support our work; subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Black voters over-represented among those arrested for election crimes