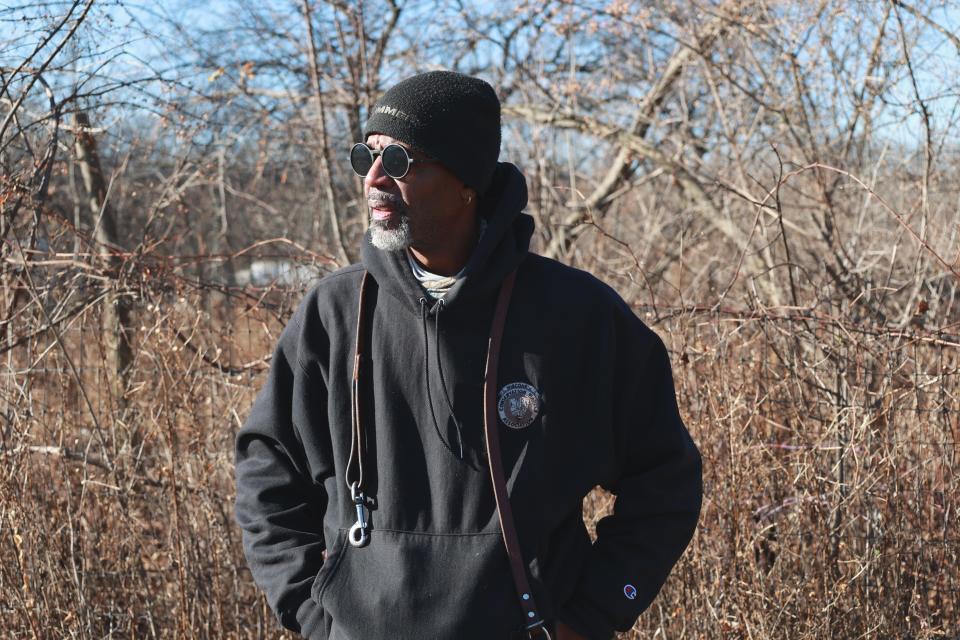

'I was the Black warden': DNR's first African American warden recounts struggle for respect

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

MADISON - For Gervis Myles, working as a conservation warden was a dream come true.

But at times, it was also a nightmare.

Myles was hired as a conservation warden in 1998 after working for the Department of Natural Resources part-time. Though he didn't know it at the time, he was the first Black conservation warden in Wisconsin.

He'd dreamed of working as a ranger abroad, protecting animals. Or a veterinarian. Becoming a warden in Milwaukee seemed like a perfect fit, being outdoors and making sure sporting enthusiasts respected the wildlife they hunted and fished.

Myles reached out to share his story after the Journal Sentinel reported on a toxic culture with the conservation warden program going back years, based on the accounts of nearly a dozen current and past employees who say the problems remain largely unaddressed. Myles said he hoped speaking out now could help bring about change.

For Myles, signs of trouble were evident from the start. Before he was even accepted into the academy, he recalls being questioned repeatedly over whether he could swim, which seemed to stem from a stereotype of Black people. In reality, he excelled at the swim test, completing his swim in a much shorter time than the limit set for the program.

When he was admitted, things did not improve.

Myles felt that the people he trained alongside at the academy only saw him as a Black warden, and not a conservation warden. He recounted tricks played on him at the Ft. McCoy academy where at least twice a month, someone would sneak into his room and tear it apart.

"I would have my books taken off the shelves and my bed would be turned upside down," he said. "It would just be disarray. It was a running joke, and I just kind of went along with it. It was kind of a mythical character who would come in and they nicknamed him the 'Funny Man.'"

Eventually, after gaining his full-fledged warden status, Myles hoped his treatment would get better.

It didn't.

"I had people refer to me as Buckwheat. They'd do a mimicking of what they would consider the way Black people walk, and jive-talking," he said, referring to the Black child character Buckwheat in the "Little Rascals" shows in the 1930s and 1940s. "I ended up not trusting a lot of people, so I would just stay to myself a lot."

After a period with the department, he applied for a new position, seeing himself as highly qualified, but was denied. Years later, he tried again. He would try two more times throughout his tenure as a warden, only to be turned down.

"I thought well, I've got a good shot at this. Let me try this," he said. "Once again, it didn't happen."

While he continued to serve as a warden in Milwaukee, creating ties with the community and teaching young kids about natural resources, he said he continued to experience a toxic culture within the warden program. When he reported issues to his superiors, no actions were taken or his claims were seemingly brushed off.

"There was not a day that I worked where I was not reminded, verbally, that I was the Black warden. I wasn't a game warden. I was a Black warden," he said. "Matter of fact, when I first got hired, one of the guys said 'Oh, we knew you were going to get hired because you were the top minority.'"

The type of treatment that Myles describes during his time with the DNR gives a portrait of a larger issue within the program, where the toxic culture has impacted employees for decades, according to nearly a dozen people who spoke with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Current and former employees spoke of a culture where sexual harassment was unchecked, management mistreated employees because of their sexual orientation, and leadership routinely retaliated against people for questioning harassment or mistreatment.

At least four employees over the last four years have filed Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaints, with some cases ending up in court.

In 2012, Myles filed a suit against the department as well, after being passed up for another open position that he saw himself as well qualified for. It was settled in 2014.

In February 2018, he had made the emotional decision to leave the department nearly five years ahead of his plan, worried about retaliation and fed up with the microaggressions from colleagues and keeping his head up through racist comments, unwarranted suspicions and disrespect.

"Your identity is wrapped up in being a warden. You wear the uniform, drive the vehicles, people know who you are," he said. "And once I gave up the uniform and the car and all that stuff, all of a sudden I was like, nobody. I went from being the Black warden to nobody."

But even losing that identity didn't dull the ache of what he had to go through in order to be a warden.

Now, he said, he's hoping by speaking up change may come.

More: Act 10 weakened the warden's union. They hope a lawsuit will bring it back to full strength

DNR, governor mum on issues within the warden program

Despite current and former employees sharing their stories about experiences within the warden program, the department has largely remained silent about the issues. Acting Secretary Steven Little declined to be interviewed by a reporter and requests to speak with Chief Warden Casey Krueger have gone unfilled.

Katie Grant, the DNR's communications director, said in response to questions about the culture within the warden program that employees are required to undergo sexual harassment training yearly, there is an equity and inclusion plan for the agency, other trainings on inclusion and for women in law enforcement were offered, and that reports of harassment or discrimination are investigated.

"The DNR will continue to prioritize creating an inclusive workplace for all and responding to allegations based upon facts, providing all involved with due process," Grant said in an email.

She declined to make any DNR leadership available for interviews.

The revelations regarding the warden program come at a time when the DNR is without a leader at the helm. Former Secretary Adam Payne stepped down at the end of October, and Gov. Tony Evers has yet to make a new appointment.

Evers' office said previously that the agency was undergoing a "climate assessment" by the Department of Administration, but did not provide more information or answer questions about the warden program.

Evers' office has been notified of issues within the warden program before, especially relating to the struggles Black wardens have faced.

In a letter sent to Evers in mid-July, another former warden pointed out issues within the program that led to their resignation.

The former warden, who asked not to be named out of fear of retaliation, pointed out that once they were out in the field, opportunities to learn were limited, and those in charge of training seemed to carry biases based on the skin color of the new wardens.

"I feel like I was trained haphazardly because of the color of my skin," the former warden wrote. "The Wisconsin Warden service has a history of targeting black men and creating obstacles for them not to succeed. I want my training experience to be investigated and I want this to never happen to another black man trying to become a Conservation Warden."

The letter went unanswered.

Ben Gruber, president of Conservation Wardens Local 1215, said the union's requests for a meeting with leadership have gone unanswered and was told by the governor's office that the issues would be looked into.

But the wardens Gruber has spoken to are hopeful now, too, that some sort of action may come from the stories being shared.

"They've expressed hope that this will lead to the objective, independent investigation that we've asked for all along, so that the people who still work here don't feel victimized by retaliation and disparate treatment, and will have a safe place to report those concerns," he said. "That's been the overwhelming response."

More: Inside the Wisconsin conservation warden program, employees allege 'a terrible, toxic culture'

'This is management's fault'

The issues within the warden program aren't new, according to past wardens and non-credentialed staff who worked alongside the wardens in the 1980s and 1990s.

For Pam Buss, who worked as a non-credentialed staff member for the warden program at the end of the 1990s, the program was dominated by males, which encouraged a certain culture. She said she was told she couldn't ask questions of her supervisors. And when she tried to advocate on behalf of women who approached her and said they had been made to feel uncomfortable by male coworkers, she was ignored.

"But it just died. It just died and went nowhere," she said.

Buss left the department in 2021 when she retired.

John Buss, her husband, worked as a warden from 1985 until his retirement in 2015.

He said he also witnessed the way women were treated by men within the program, and while it never amounted to physical harm, he saw the toll it took on the women mentally. Many of the qualified women he saw come into the program left after the treatment they received.

"Management deserves credit when things are going good. But management deserves discredit when things are going bad," he said. "This is management's fault. This has been coming."

Buss had his own negative experiences with leadership.

In the 1980s, Buss was a witness to an officer-involved shooting in Baraboo. He assisted a police officer with handcuffing a man after he was pulled from his vehicle for drug possession. But when Buss turned his back to call in the incident, the police officer shot the man in handcuffs, killing him. The officer turned the gun on Buss, who was able to talk him into putting the gun down.

Buss said he's struggled to overcome the incident from decades ago, attending therapy and doing what he can to honor the day it happened — September 16, 1985.

During a target practice session, a fellow warden made a joke about "gray matter" after landing a shot to a dummy's head. Buss tried to explain why the comment was upsetting, particularly after witnessing the shooting, but management failed to hear his concerns for himself and others who may have endured situations like his.

"I didn't view that as any major attack against me, but I suffered silently when I got home," he said.

Another former warden, who spoke with the Journal Sentinel on the condition of not being named in the story due to a non-disclosure agreement signed during a settlement with the agency, said leadership didn't take mental health seriously.

The area the person worked in within the program was understaffed, and a retirement meant additional workload, the former warden said, who sought help from mental health care professionals.

"I told them what I was going through and how this was affecting my family and they could care less. Their standard answer is to direct you to the Employee Assistance Program and then they distance themselves from you," the former warden said. "It's a very unpleasant and eerie feeling."

The former warden then sent the department a document outlining long-term issues in the area they worked in, citing the workload, a lack of staff and a lack of assistance from superiors. Soon after, the former warden received a letter from HR with a "laundry list of policy violations."

The former warden was terminated and filed an appeal. After a lengthy court battle, the case was settled.

"I was maxed out mentally, financially and physically," they said. "I just wanted to get it over with."

But the whole process felt like an attack, the former warden said, for calling out issues with workload and inadequate help from management and after informing them of a mental health diagnosis.

"They're just extremely vindictive," the former warden said.

Laura Schulte can be reached at leschulte@jrn.com and on X at @SchulteLaura.

THANK YOU: Subscribers' support makes this work possible. Help us share the knowledge by buying a gift subscription.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: DNR's first Black game warden recounts struggle for respect