The Black and White Partners Who Brought Voting Rights to Mississippi

In Mississippi, the emphasis of the civil rights struggle had shifted from direct-action campaigns involving sit-ins and protest demonstrations to the task of voter registration. The landmark Civil Rights Act, which swept aside legal footing for racial discrimination in public accommodations in 1964, led to the enactment of a companion Voting Rights Act a year later.

The latest congressional action was spurred by an assault by a mounted sheriff’s posse on a march by voting-rights supporters in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965. Scenes of the violence—reminiscent of raids by murderous Cossacks during Eastern European pogroms—were carried on national television, provoking widespread indignation and a determination by President Johnson to win passage of the bill. It was another instance where terror by extremist defenders of racist codes proved counterproductive. As many southern whites began to recoil from the violence, recognizing that it was no longer helpful in preserving segregation, the reputation of the Klan was further diminished. Still, the White Knights attracted zealots prepared to use any means to fight off change even though they appeared to be engaged in a losing battle.

Eight years after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the University of Mississippi had been integrated, and two years later the Civil Rights Act finally gave Blacks the right to eat in cafés, stay overnight in hotels, and attend theaters that had previously been segregated. Nonviolent defenders of the Lost Cause turned to new tactics. They felt racial integration could be circumvented bloodlessly by establishing all-white private academies and turning public establishments into clubs.

Extending voting rights to Blacks, however, posed a different and more significant threat for the segregationists, because it could not be easily overcome by an end run around federal law. It raised the specter of Black voting power, which could undo the political structure of the region. With Blacks accounting for nearly half of the population of Mississippi, the legislation could cause a cultural earthquake. Blacks would become a pivotal force at the polls, and in the rich land of the Delta, where their number dominated the population, they were poised to take over the government of cities and counties. For these reasons, critical battle lines were being drawn.

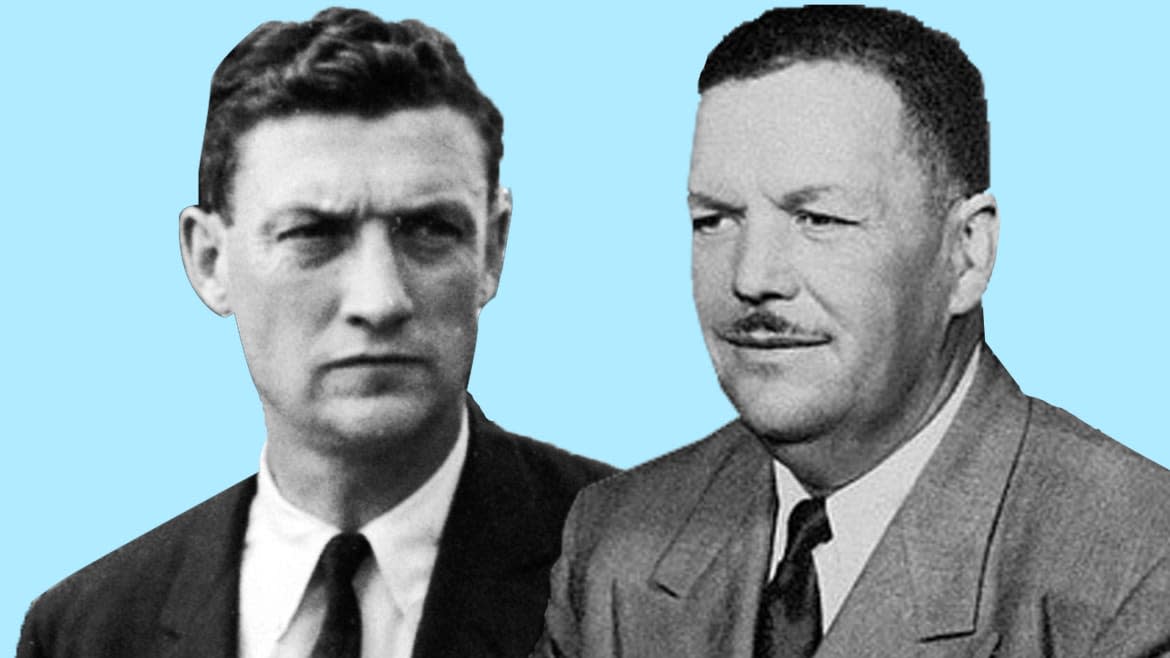

Honoring the Late John Doar, a Nearly Forgotten Hero of the Civil Rights Era

The federal legislation of 1965 was designed to eliminate barriers thrown up by segregationists to prevent Blacks from registering to vote by employing capricious literacy tests, poll taxes, requirements for property ownership, and arbitrary judgments by voting registrars on the moral character of applicants. The Voting Rights Act would diminish the power of circuit clerks like Leonard Caves in Jones County, his counterpart next door in Forrest County, Theron Lynd, and John Wood of nearby Walthall County, who once became so annoyed with a Black applicant that he pistol-whipped him on the way out of his office.

The law provided stronger teeth for the U.S. Justice Department, whose civil rights division had already been actively investigating voting-rights abuses in Mississippi and working in tandem with grassroots organizers intent on increasing opportunities for registration. The division was the product of the twentieth century’s first civil rights act, in 1957, which gave Justice Department officials limited authority to implement Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment provisions dealing with voting rights.

The most impressive figure among the government lawyers sent to the South in the early sixties was Wisconsin Republican John Doar, the number two man in the civil rights division, a unit filled with recent law school graduates dedicated to the activism espoused by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Though Doar was in his forties, few of his more youthful associates could match his tireless enthusiasm for his job. Instead of operating out of bureaucratic Washington, Doar beat the backcountry bushes. He made personal contacts with many local Blacks, listening to their grievances and winning their trust when it became obvious that he was committed to the mission.

Doar was the first government official to meet with Vernon Dahmer, who by this time had been largely working in vain to register Blacks in Forrest County. While FBI agents traveled in Mississippi in pairs, dressed in dark suits like Mormon missionaries per Director Hoover’s orders, Doar often moved about by himself in informal clothing more compatible with the people he visited. One of the first men he sought out was Dahmer, whose involvement in voting-rights activity was well known in the area. They met at Dahmer’s farm, where Doar’s host itemized a history of discrimination in Forrest County. A sense of mutual respect developed immediately. There was nothing flamboyant about either man; each went about his business in a no-nonsense style.

Doar was also unique in that he recognized the importance of building constructive relationships with journalists, who were beginning to cover the movement with interest. He tried to be responsive to their questions, and sometimes he offered inside guidance on stories. He had enough respect among the national reporters to entice them to follow his efforts in out-of-the-way places.

One of Doar’s earliest targets was Forrest County. After he learned of the repeated rebuffs encountered by each Black who went—sometimes escorted by Dahmer—to the circuit clerk’s office in Hattiesburg to try to register to vote, Doar and his lieutenants began compiling a dossier. With Dahmer’s help, the Justice Department lawyers drew up a list of credible men and women in Forrest County who were prepared to attest to their experiences at the hands of the circuit clerk for the country, Theron Lynd. Doar believed he would be able to document that these potential witnesses had given acceptable answers to Lynd’s literacy test but had been failed by him without any explanation.

By Mississippi standards, Forrest County was relatively urban and cosmopolitan. It not only encompassed Mississippi Southern College and a smaller Baptist institution, William Carey College, it was the home of Camp Shelby, a giant army installation that had processed thousands of recruits during World War II and remained a major training base, which helped drive the local economy. Though Hattiesburg was one of the larger cities in the state, county officials ran the place as if it were a rural backwater where they felt free to impose any steps necessary to maintain white supremacy.

The procedure for voter registration at the Forrest County courthouse was contrived to represent an insurmountable obstacle for Blacks. Those who came to the circuit clerk’s counter were disregarded or told to wait. White women among the personnel in the office were informed that they would not have to deal with any Black people; only Lynd, the elected clerk, had responsibility for seeing them, and he was invariably unavailable. When he deigned to meet with a Black applicant his manner was brusque and unyielding.

For the consumption of white voters in the county, Lynd liked to boast that no Black had been registered in Forrest County since he became circuit clerk in 1959. Lynd had run unsuccessfully for the office in 1955 against Luther Cox, the Forrest County official who had denied Dahmer’s attempt to re-register as a voter following the 1949 plot to cleanse the voting rolls of all Blacks. Cox, claiming he had been able to block all but a handful of Black applicants over the years, was reelected. But after Cox’s death, Lynd won a special election and set about bettering his record of intransigence.

Lynd was an exemplar of the “good ole boy” politicians of the time. He fit comfortably into the white environment of Hattiesburg, where he had played high school football. He graduated with a business degree from Mississippi State College and worked for a while for his father’s gasoline-distribution firm, rising from a service station operator to an office manager, before going into politics. For respectability, he was an active Mason and a member of a Methodist church. He promised to keep preventing Blacks from voting.

Like many functionaries, Lynd had an important patron, a Hattiesburg lawyer named M. M. Roberts, a reactionary who had an influential role in the state’s powerful segregationist bloc that elected Ross Barnett governor in 1959. Roberts had served as president of the state bar association in 1956 and, as a Barnett appointee, became a central figure on the board of trustees of the Institutions of Higher Learning, the “college board” that plunged the state into chaos by defying federal court orders over the integration at Ole Miss in 1962. Roberts was a veteran of fights dealing with discrimination. He had been the lead attorney representing Luther Cox when a group of disenfranchised Black men—led by Dahmer—filed a complaint as early as 1951, and he was eager to defend Lynd a decade later.

Despite Lynd’s authority, he became a perfect foil for Doar and Dahmer. Not only was Lynd vulnerable to charges that he conducted the circuit clerk’s affairs in a questionable fashion, he fit the physical stereotype of a southern bigot. He weighed nearly 350 pounds, his belly so massive that the top of his high-riding pants fit just below his armpits. He kept a cigar clamped between his teeth and mastered a way of talking without removing it. He favored black horn-rimmed glasses and his receding hairline revealed a bulbous, pasty forehead.

Renowned for his rudeness, Lynd seemed to take pleasure in his power to turn back a parade of Forrest County Blacks seeking to sign up as voters. Some were laborers and farmers recruited by Dahmer. Others were college-educated teachers and ministers who went to the courthouse on their own initiative. All were rejected.

“So, it’s you again,” Lynd snapped one day, seeing Dahmer in his office. He proceeded to lecture Dahmer on the importance of ensuring that only literate citizens held the balance of power for democracy, that elections should never be thrown into the hands of ignorant people.

Lynd may not have known it at the time, but Dahmer and his friends were producing for John Doar a number of local people prepared to testify against the circuit clerk. Meanwhile, Justice Department lawyers were collecting evidence of discriminatory practices in other places, as well, as they built a legal assault on circuit clerks in the state. In George County, just south of Forrest County, it was found that the clerk usually asked applicants to interpret Section 30 of the Mississippi Constitution—“There shall be no imprisonment for debt”—in order to pass the literacy test. Blacks were failed, regardless of their answers, but an inspection of documents showed that one white applicant had passed with a particularly interesting written interpretation of the law: “I thank that a nearger Should have 2 years in college Be for voting. Be Cause he don’t under Stand.”

The situation in Forrest County proved to be so outrageous that in July 1961, only six months into the Kennedy administration and four years before the voting-rights legislation passed, the Justice Department filed suit against Lynd to seek injunctive relief. Much of the evidence involved material turned over to the government lawyers by Dahmer, who had been happy to share his frustrations with sympathetic officials.

The trial began in Jackson in March 1962, and the first witness for the government was Jesse Stegall, an earnest thirty-year-old principal at a Black elementary school in Hattiesburg who had graduated from Jackson State, a leading four-year state college for Blacks. He was not only literate, he was erudite. While a student, he had met such prominent Black writers as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Margaret Walker Alexander.

Stegall was one of five teachers included in the government’s roster of witnesses who held advanced degrees but had flunked Lynd’s literacy test. He knew that by testifying he would risk his job, which he needed to support his wife and their child. “We were not going down to the circuit clerk’s office to be troublemakers,” he said of his motivation. “We were going down to get our right to vote. And when you were going down to register to vote and these barricades are placed before you, you get frustrated until it really angers you.”

Stegall told of an attempt he and a fellow teacher, David Roberson, made to register to vote in 1960:

Mr. Lynd came to the counter where Mr. Roberson and I had walked and asked, “What do you boys want?”

I stated, “I came to find out procedures on which to register.”

He said, “What’s your name?” I told him my name. He asked what did I do. I told him my occupation. He asked where I lived. I told him that also. And then he said, “No, I can’t register you.” He said he did not have the time. I asked, when would it be possible for me to see him when he had the time. He said he did not know.

Stegall and two other teachers did not return to the circuit clerk’s office until nearly a year later, when they were emboldened by knowledge that the Kennedy Justice Department was trying to facilitate voter registration. But they were again discouraged by Lynd, who told them, “I can’t handle all of you at the same time. You will have some papers to fill out.” It was past four in the afternoon, and Lynd said, “If you do not finish by five o’clock you will have to begin all over.”

The trio left and returned early the next day. Stegall was given an application form and a section of the Mississippi Constitution to interpret that dealt with chartering corporations. Taking a half hour, Stegall provided Lynd with a clear, written interpretation of the section, a document that was introduced into evidence.

Stegall testified that a week later he went to Lynd’s office to see if he had passed. Lynd told him no. Asked what part of his application had failed, Lynd said, “I can’t divulge that information.” He told Stegall he would have to wait another six months before applying again. Stegall, who held a PhD, said he tried six times to register and failed each time.

Presiding over the trial was the U.S. district judge Harold Cox, a close friend of Senator Jim Eastland of Mississippi, who had prevailed on the Kennedy administration to nominate him for the judgeship. Cox was another important cog in the state’s political power structure. To the Justice Department attorneys, it appeared obvious that Cox would favor Lynd and his attorney, M. M. Roberts, and give little regard to Doar, who led the government case. After Judge Cox declared a thirty-day hiatus, the Justice Department appealed the case to a more friendly venue, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, before the trial could be completed. A three-judge panel responded with an injunction against Lynd, noting that “the witnesses produced by the government proved without question that certain serious discrimination had taken place during the term of office of the defendant Lynd.”

In spite of the order to discontinue his pattern of rejecting qualified Black applicants, Lynd continued the practice. After Dahmer and his son Harold went to the courthouse to register following the injunction, they had trouble finding the circuit clerk. When they appeared at Lynd’s office, they were told he was upstairs in a courtroom. The Dahmers found the courtroom empty. Coming back downstairs, they caught Lynd leaving the office. He allowed the two men to fill out an application form, but when they checked back later Lynd told them they had failed and refused to give a further explanation.

In the face of Lynd’s recalcitrance, the Justice Department went back to the Fifth Circuit seeking a contempt charge against him, and setting up a new trial in September 1962, in the midst of the climactic legal battle over the integration of Ole Miss that consumed national headlines and much of the court’s attention.

Finally, on July 14, 1963, Lynd was found in contempt. As part of the order, forty-three Blacks who had attempted to register after the original injunction against Lynd were put on the voting rolls. Vernon Dahmer and his son were in the group.

Dahmer drew energy from the court victory. Although it came only a month after the assassination in Jackson of his friend and NAACP associate Medgar Evers, Dahmer was unintimidated and threw himself into the movement, which was gaining momentum. He and B. F. Bourn, his longtime ally in the battle in Forrest County, embraced the activities of a new generation of volunteers willing to sacrifice themselves. Although Dahmer and Bourn realized their old organization, the NAACP, was thought stodgy by many of the young volunteers coming from more radical groups such as SNCC, they developed a rapport with the activists.

Among them was Lawrence Guyot, the twenty-four-year-old activist who had been involved in the Hattiesburg Project and returned to help win support from the National Council of Churches for a voter-registration demonstration in Hattiesburg. The labors of the young Turks in the movement, combined with the groundwork carried out by local people like Dahmer, contributed to the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Armed, at last, with federal law in 1965, Dahmer redoubled his efforts as the year came to an end. He turned his little country store, next to his home, into an unofficial clinic for voter registration. The fifty-seven-year-old farmer, who had spent the years after World War II as an obscure irritant to the white leadership in his home county, was emerging as a major figure in a state bristling with challenge and resistance by Blacks. After years of struggle, Dahmer’s work had attracted not only the attention of government officials like John Doar but recognition that he was a significant player in the movement.

His renown had another effect. In the eyes of the devoted racists in the state, he had become a menace. If Dahmer could not be stopped by state laws or the whims of segregationist circuit clerks, and if the feeble efforts of the United Klans affiliates in Forrest County were unable to control him, the job fell to the White Knights in neighboring Jones County to put an end to his activities.

Excerpted from When Evil Lived in Laurel: The "White Knights" and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer. Copyright © 2021 by Curtis Wilkie. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.