For Black women judges like Jackson, blazing a trail has meant opportunity, scrutiny

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON – By 1966, U.S. District Judge Constance Baker Motley had smashed every barrier in her path, winning some of the biggest legal battles of the civil rights era and securing a spot in history as the first Black woman to preside over a federal court.

But Motley, who had worked under armed guard in the Jim Crow South, initially felt uncomfortable with the simple act of grabbing a sandwich in the courthouse cafeteria.

The unease Motley felt was the result of a run-in with another federal judge in New York who made it clear she wasn’t welcome to eat with her colleagues, an example of the small slights and open hostility often faced by trailblazers like her.

President Joe Biden’s Supreme Court nominee – Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson – broke ground on Friday as the first Black woman picked for the nation's highest court. If confirmed to succeed Associate Justice Stephen Breyer, she will join a cohort of women like Motley who confronted racial and gender discrimination over the course of distinguished legal careers.

Like Motley, Jackson, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, may well serve as a role model to younger generations.

"Today, I proudly stand on Judge Motley's shoulders," Jackson said at the White House, noting that she shared not only a birthday with the civil rights icon but also "her steadfast and courageous commitment to equal justice under law."

No one expects Jackson to encounter the kind of brazen discrimination Motley endured six decades ago. At the same time, experts and former Black women judges say Jackson will likely face a degree of additional scrutiny unfamiliar to her white, male counterparts. Even before Biden announced his nominee, one Republican senator compared the president's decision to name a Black woman to affirmative action.

First Black woman: Jackson says she's 'humbled' by historic nomination to Supreme Court

Making history: What to know about Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson

"We have some work to do in this space for sure because I'm hearing the same concerns raised from some quarters," said Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. "We're very clear that when it's a person of color, we identify the race or when it's a woman, we identify the gender. White men also have a race and gender that may affect how they approach particular matters."

When Motley first became a judge, "she did have to deal with a lot, although she was always gracious about it,” said Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who tells the cafeteria anecdote in her new biography of Motley, "Civil Rights Queen."

“While it is important to say I do not think that this nominee is going to experience anything like what Motley experienced in terms of just outright disrespect, that is the context for this breakthrough appointment,” said Brown-Nagin, who is the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and a legal historian at Harvard University.

Assuming she is confirmed by the Senate, Jackson will follow other trailblazing women, including Judge Jane Bolin, the first Black woman to serve as a judge anywhere in the nation. Judge Amalya Kearse, in 1979, became the first Black woman named to a federal appeals court. Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor in 2009 became the first Latina and first woman of color seated on the nation’s highest court.

More:GOP signals fight over 'dark money' in Supreme Court confirmation battle

While the numbers are growing, Black women have historically made up a tiny fraction of the federal judiciary. Only 70 of the 3,843 people who have served as federal judges have been Black women, according to the Pew Research Center. When Black women are named to courts, their race and gender are often highlighted – and celebrated – but that can lead to assumptions that rarely apply to white men, observers say.

Judge LaDoris Cordell was the first African American female judge in Northern California, having served on the state’s Superior Court beginning in 1982. Cordell described some of the assumptions that people made about her jurisprudence early on, such as that she’d be soft on crime. There was also pressure from the Black community, she said, to not "screw up" for fear that if she made a mistake it would be harder for other Black women to follow her.

"There's those pressures to not to fail. And then the expectation that you will fail," said Cordell, who last year published a book, "Her Honor," about her experiences on the bench. "That's all built on stereotypes that she shouldn't be there anyway."

"The thing is," Cordell said, "it’s still going on today."

Legal pioneers

When New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in 1939 named Bolin to what would become the city’s family court, he initially "ignored" her altogether. Instead, according to an interview Bolin gave the New York Times years later, the mayor first pulled Bolin’s husband into another room and told him about the appointment first.

"When they came out, my husband was smiling, and the mayor said to me: 'I'm going to make you a judge. Raise your right hand,'" Bolin told the Times in 1993.

Bolin, the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School, joined New York City's legal department in the early 1930s. As a judge, she challenged the assignment of probation officers based on race, according to a 2011 biography, "Daughter of the Empire State," and organized a letter writing campaign to take on La Guardia and other city officials to call attention to segregated housing in the city.

Years later, Motley would describe Bolin as a role model. And on Friday, Jackson looked to history and paid the same respect to Motley.

"Judge Motley's life and career has been a true inspiration to me as I have pursued this professional path," she said as she stood next to Biden.

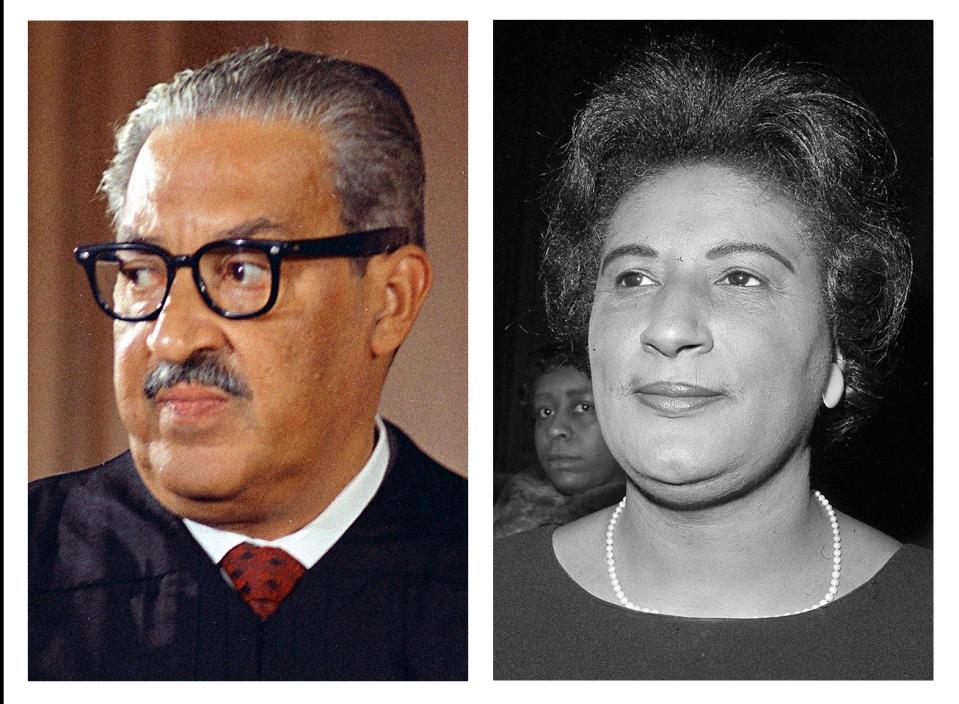

Unable to find work in private practice, Motley would have a pioneering legal career as a civil rights lawyer, successfully litigating James Meredith's 1961 challenge to the whites-only admission policy of the University of Mississippi. She wrote the original complaint in Brown v. Board of Education, the case that led to the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling ending state-imposed segregation in public schools. A protégé of Thurgood Marshall before he became the first African American justice on the Supreme Court in 1967, Motley argued 10 cases before the high court. She won nine of them.

In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson nominated Motley to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in Manhattan, among the most prominent federal courts in the nation.

In one of her most often cited cases, Motley was asked to decide if a law firm had violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by discriminating against women attorneys. Before she could reach the merits of the case, Motley had to address a request from the firm to recuse herself because she was a woman.

Diversity: Biden wants to put a Black woman on the Supreme Court

Triple: Biden poised to triple number of Black women on federal appeals courts

Talking about race: Why Americans have such a hard time talking about equity for Black women

In her book, Brown-Nagin highlighted a 1975 letter from one of the firm's lawyers arguing for Motley's recusal. Motley, the lawyer wrote, might "have a mindset that may tend, without your being aware of it, to influence your judgment." Motley waved it away, noting in an order that every judge has a race, a gender and a background.

"If background or sex or race of each judge were, by definition, sufficient grounds for removal, no judge on this court could hear this case, or many others, by virtue of the fact that all of them were attorneys, of a sex, often with distinguished law firm or public service backgrounds," Motley wrote.

The law firm ultimately settled the case.

Motley would become chief judge for the Southern District in 1982. By then, when she avoided the cafeteria, her son Joel Motley said, it was more likely to be because "she didn’t want to be bothered with requests" from her colleagues.

Joel Motley said he believes his mother, who died in 2005, would have been proud of what Biden's nomination represents. She also would have been proud of the growing if halting diversity in the nation's lower federal courts, he said.

"There's a huge demographic change in the judiciary, nationally, both federal and state,” said Motley, who produced a documentary about his mother in 2015, "The Trials of Constance Baker Motley."

"You can say, 'isn't it frustrating that we're inching and clawing our way up to our first Black woman Supreme Court justice?’ Well, yes, that's true, but look at the number of Black women there are to choose from."

'Wise Latina'

That doesn’t mean it’s been easy.

The Senate last wrestled with race and gender in a Supreme Court confirmation hearing in 2009 after President Barack Obama nominated Sotomayor.

Though otherwise free from controversy, some Senate Republicans zeroed in on Sotomayor’s past speeches in which she expressed hope that "a wise Latina woman, with the richness of her experiences, would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life."

During her confirmation hearing, Sotomayor said she was attempting to inspire students to believe that “their life experiences would enrich the legal system” but she also acknowledged that her "rhetorical flourish" was a "bad idea."

Women: Meet the women who preceded Amy Coney Barrett on the Supreme Court

RIP RBG: Second woman on Supreme Court had been nation's leading litigator for women's rights

The attention on Sotomayor’s words pointed to a much deeper debate about how much a jurist’s background influences how they do the job of interpreting the law. It’s a discussion likely to come up this spring when Jackson appears for her own hearing.

“Aren’t you saying there that you expect your background and heritage to influence your decision making?” asked Jeff Sessions of Alabama, who was at the time the top Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

"Life experiences have to influence you. We’re not robots (who) listen to evidence and don’t have feelings," Sotomayor said. "We have to recognize those feelings and put them aside. That’s what my speech was saying. That’s our job."

What is often overlooked, Ifill and other experts say, is that race and gender affect how white men look at the law, too. That's the point Motley was making in her order.

"It's a tough balance," said Angela Robinson, a visiting professor at the Quinnipiac University School of Law and a former Connecticut Superior Court judge who recently published "First Black Women Judges," a book about three historic jurists of color. "Because you're a Black woman, there's an assumption if you do come out a certain way on a certain issue that has to do with race, that you did it because of identity, which is so unfair."

"We don't think of white men judges who come out in a certain way are only doing that because of their race."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Supreme Court pick Ketanji Brown Jackson can look to these pioneers