Black women are not angry, but passionate. They have been silenced for too long. | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Americans have often mistaken Black women's passionate attitude for anger. Black women have experienced tone policing when at work, at corporate gatherings and in public life.

Over last few years, society has been forced to pay attention to the systemic racism against African Americans. People of all races have marched and protested to encourage change — changes that require people not only to focus on the justice system but to focus on conversations that dim the light on racial tropes.

Despite the effort for change, Black women still feel the need to alter themselves to gain acceptance.

In 2019, former First Lady Michelle Obama spoke with CBS news host Gayle King and explained during an interview how being called "angry" affected her work ethic when she served as the First Lady of the United States.

“For a minute there, I was an angry Black woman who was emasculating her husband," Obama said.

"I had to prove that not only was I smart and strategic, but I had to work harder than any First Lady in history,” said Obama, recalling the label she was given by critics for speaking against racism and other harsh topics.

More: How Stacey Abrams can teach all citizens to be resilient leaders | Opinion

Powerful women like Harris and Abrams are targeted

Vice President Kamala Harris and Stacey Abrams, the 2018 and 2022 Georgia governor's race candidate, experienced similar name-calling when expressing themselves.

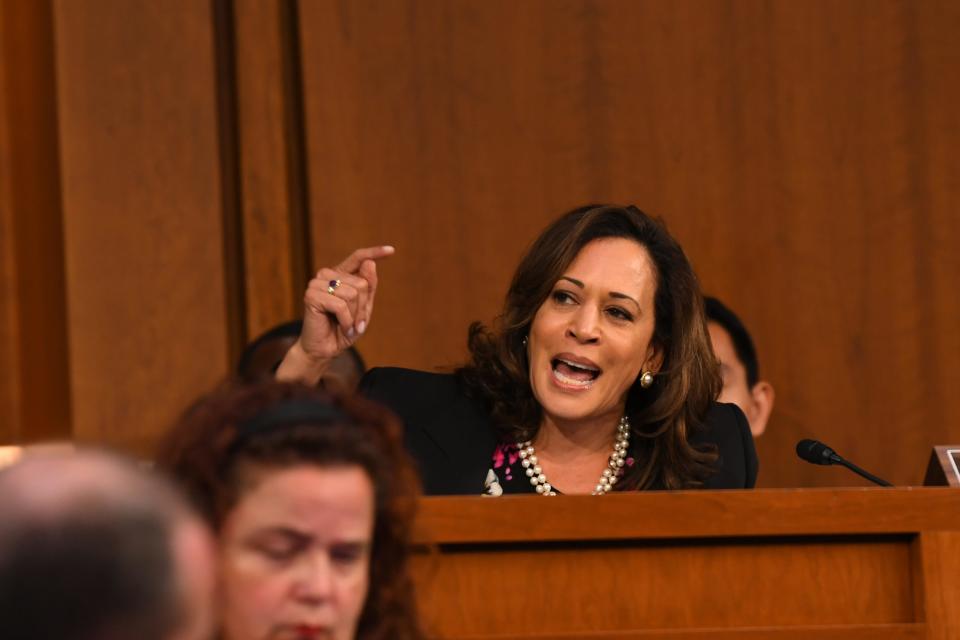

Harris, who identifies as Black and Indian American, was called a "madwoman" by former President Donald Trump after she questioned Brett Kavanaugh about sexual misconduct allegations during his 2018 confirmation hearing.

"And now, you have — a sort of — a madwoman, I call her, because she was so angry and such hatred with Justice Kavanaugh. I mean, I've never seen anything like it. She was the angriest of the group and they were all angry,” Trump said.

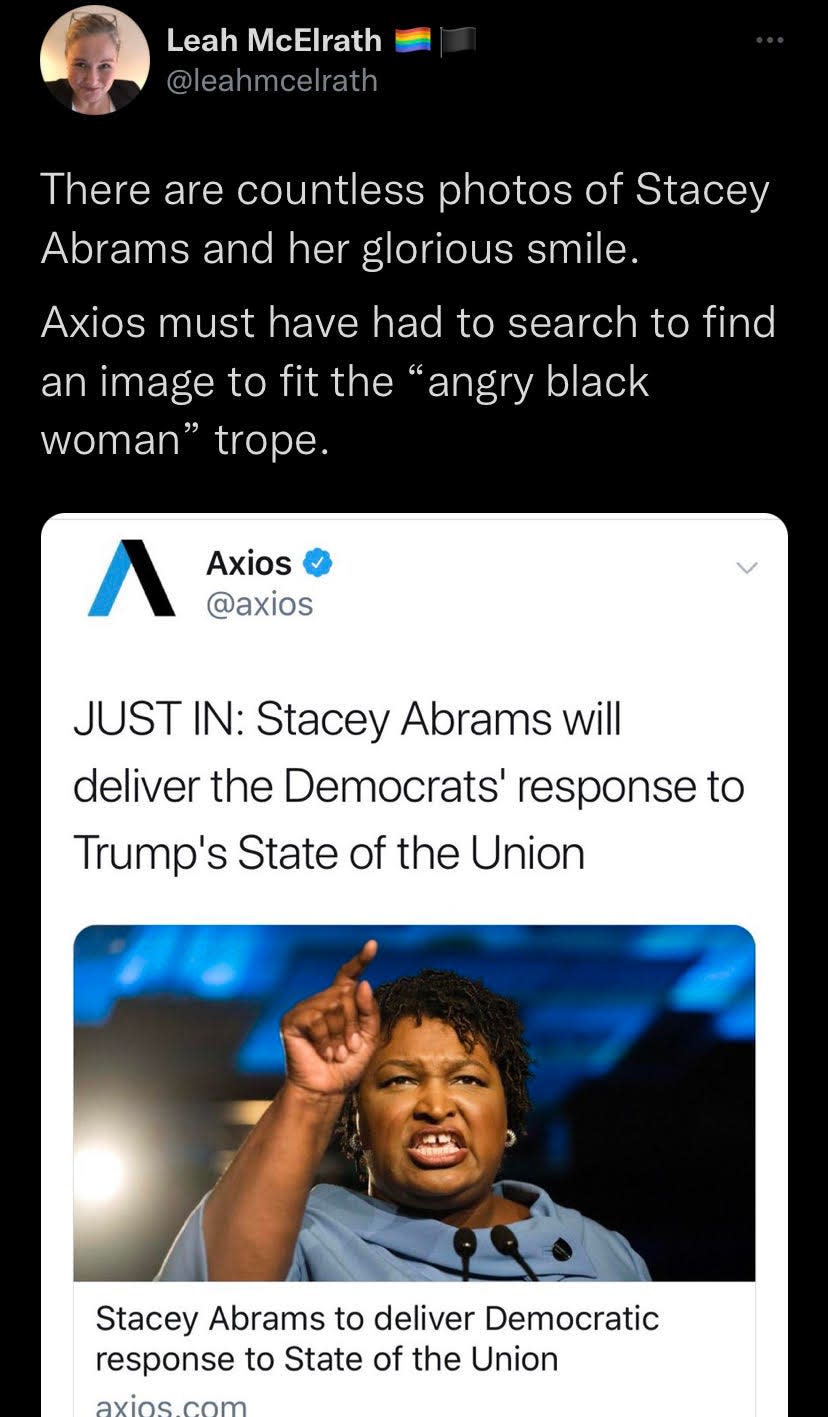

Twitter users were offended when Axios, a political news site, uploaded a photo of Abrams that users felt played into the "angry Black woman" trope.

One user said, "there are countless photos of Stacey Abrams and her glorious smile. Axios must have had to search to find an image to fit the angry Black woman trope."

The “Angry Black Woman” trope has been given to African American women throughout history.

Many Black women have struggled with this label in their professional and personal lives. Black women are afraid to speak in work environments to dodge being given the title angry.

More: Each time another black person is killed by police, all I can say is: 'Again?' | Opinion

How microaggressions can keep some Black women silent

As a Black woman, I have filtered my opinion during conversations with people from other races in the past. I would refuse to engage in topics my freshman year of college. I felt voiceless as I attended a predominately white institution.

I recall a time when I studied with a few girls from my dorm room and a couple of their friends. I was the only Black person in the group. We discussed various topics that day, but one particular topic I stayed quiet on.

That topic was why the African American race was proud to see a president that looked like them. Comments and questions were thrown out there.

For instance, one girl asked, "Why do Black people act so excited when a Black person does something that supposedly makes history, but when a white person does something that makes history, the same excitement isn't shown?"

At that moment, I was tight-lipped. I thought her question was insensitive. I was sitting at a table with people who did not look like me and people who openly downplayed the achievements of Black people in my presence.

I felt she did not understand how significant a Black person elected as the president of the United States was. She appeared to either forget or ignore the unjust treatment and control the African American race endured over four centuries.

Maybe she never knew, but this is a reaction I have seen from some white people who minimize historical achievements for Black people.

Believe it or not, I was not angry. I would have liked to answer her question, but I chose not to. I did not feel I was in an open-minded space to communicate. My entire study group acted oblivious to why my race would be proud to achieve historical milestones. Jokes were thrown around constantly.

Her tone when she asked the question was like she was asking a rhetorical question. While I was able to answer her question, I wasn't willing.

At that moment, I lost my confidence and voice.

Your state. Your stories. Support more reporting like this.

A subscription gives you unlimited access to stories across Tennessee that make a difference in your life and the lives of those around you. Click here to become a subscriber.

More: Tennessee black writers talk about racism, social unrest and next steps

How I recovered my voice

Now, after being influenced by women who look like me, my voice has returned. My words have grown stronger. I realize that using my voice to discuss harsh truths in America shows I was strong enough to indulge in complex conversations.

Among those times I used my voice, I was not enraged, instead, I was passionate.

As I watched a 2016 interview of Michelle Obama by Oprah Winfrey, I was deeply moved by how the former First Lady chose to transform her pain instead of transmitting it.

She told Winfrey, "The thing that least defines us as people is the color of our skin, it's the size of our bank account. None of that matters. It's our values, it's how we live our lives. You can't tell that by someone's race, someone's religion. People have to act it out, they have to live those lives so that was the blowback, but then I thought okay, let me live my life out loud so people can then see and then judge for themselves."

Like Obama, Abrams channeled her anger into change as she recently announced she is running for governor again after nearly winning the 2018 election and accusing her opponent of suppressing Black votes.

Despite critics painting her as angry, she refuses to be discouraged. Both women could have spread negativity after critics portrayed them as angry individuals. Both continued to be positive and focused on what mattered the most.

Michelle Obama's words were confirmation Black women should not silence themselves. Black women did not label themselves angry. Black women have been forced to be the face of this negative trope for decades.

Katelynn White worked as a news intern for the USA TODAY Network Tennessee in late 2021 and graduated from Tennessee State University summa cum laude. Feel free to contact her at KWhite@nashvill.gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Black women like Obama, Harris, and Abrams are passionate, not angry