'Blacklisted' Afghan interpreters were disqualified from U.S. visas. Now they're in hiding

As an expert in explosive device removal, H.S. spent nearly three decades carefully cleaning up land mines and disabling unexploded bombs planted by insurgent groups in Afghanistan.

During the last 12 years of his career, H.S. — whom The Times is identifying by his initials for his safety — worked as an interpreter for U.S. government contractors training Afghan national police and army forces to do his job. A supervisor said his dedication and experience made him irreplaceable.

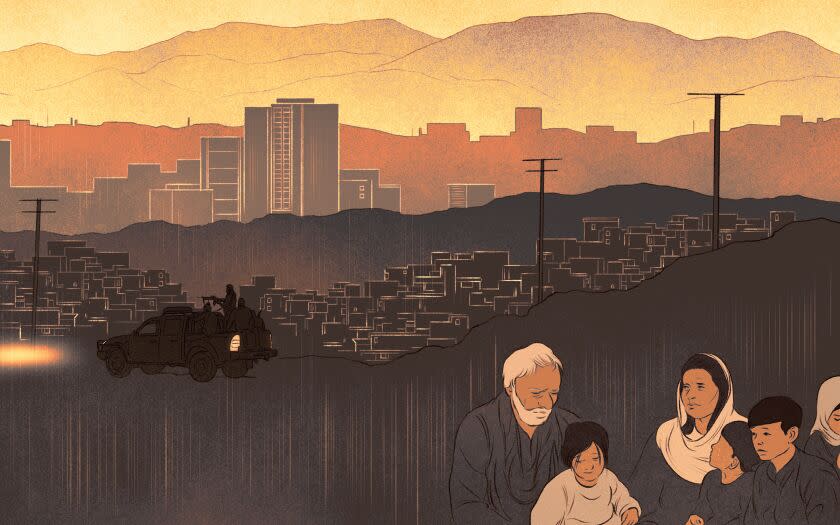

But H.S. said that in 2020 he failed a counterintelligence screening after mixing up the Western and Afghan calendars when telling an agent the date of a work trip to Pakistan. As a result, H.S. was fired and his application for a U.S. visa was denied in 2021, just a few months before the remaining U.S. troops left his country as the Taliban took power. He spent most of the last year in hiding north of Kabul, the Afghan capital.

“I can’t continue my life like this,” he said. “The Taliban, if they find me, they will send me to jail or kill me.”

The rapid and disorganized exit from Afghanistan a year ago left many people in danger under Taliban rule. Among them are interpreters like H.S., who refer to themselves as "blacklisted" and say they were unjustly barred from getting visas promised to Afghans who helped the U.S. Advocacy groups such as the International Refugee Assistance Project say thousands have been affected.

The State Department declined to comment on individual cases.

The Times interviewed two dozen people about the issue, including interpreters, U.S. supervisors, advocates and lawyers, and reviewed hundreds of pages of internal State Department communications, government reports and visa applications. The interpreters who spoke to The Times said their visa petitions were denied despite receiving positive reviews from their military supervisors. In most cases, the denials came after the interpreters were terminated by the private contracting companies that hired them.

No One Left Behind, a service organization that assists Afghan and Iraqi interpreters, counted 339 killings of special immigrant visa, or SIV, applicants by the Taliban throughout the war until late 2021, though the nonprofit considers it an undercount.

"There is no future for these people in Afghanistan," said Matt Zeller, senior advisor to the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America who co-founded No One Left Behind. "Every day that they are not able to get to America is an additional day that the Taliban has to hunt them down."

Special immigrant visas provide green cards to foreign nationals including Afghans under a variety of programs, typically because of their employment with or on behalf of the U.S. government. One requirement is "faithful and valuable service to the U.S. government."

Applicants who have been terminated "for cause" by their employers — for reasons such as failing a counterintelligence screening or for alleged performance issues — are deemed to have not fulfilled the requirement. Security screenings routinely include polygraph tests, though they are considered too unreliable to be admissible in many courts. Interpreters and advocates said the smallest inconsistency could trigger a denial.

Human resources records also might incorrectly classify someone as terminated when the person actually resigned, according to the International Refugee Assistance Project, or IRAP, and other interpreters have been found ineligible if they worked for a company accused of wrongdoing in government contracts.

Though the State Department’s internal guidance says that disciplinary action doesn’t automatically disqualify an employee and that their record as a whole should be taken into consideration, the agency has "with rare exception" denied applicants who were terminated for cause, according to IRAP. A spokesperson for the agency did not comment on how many of those appeals have been granted.

The first phase in SIV processing is an application for approval from the State Department’s Afghanistan chief of mission to verify employment, including a letter from an employer’s human resources department, a recommendation from a supervisor and a statement about threats received because of the person's work. In a 2020 report, IRAP said the State Department should stop relying solely “on HR records from private companies that are often inaccurate or incomplete,” and reopen applications when it becomes aware of mistakes or missing evidence.

As of July, there were more than 74,000 principal applicants — not including family members — in the Afghan SIV pipeline, according to the State Department. Applicants have typically waited four years for a decision, though the State Department recently increased staffing. A senior official said about half of those seeking approval are turned down at that point “for either not having the right documentation or not being eligible for various reasons.”

H.S.' application was rejected for "derogatory" information — defined by the State Department as having engaged in unlawful, unethical, criminal or terrorism-related activity — and a lack of faithful service based on his termination. He wasn't given more details, but he contends that his 12 years collectively working with the U.S. military helped train thousands of Afghan army and police forces in bomb removal techniques, which saved the lives of countless American soldiers.

H.S. used to travel to and from work in civilian clothes to avoid being identified. Now the Taliban recognizes him as a target, he said: Its members have threatened him over the phone and ordered shopkeepers in his neighborhood and the local mosque leader to call them if he is spotted. They also visited his family’s home in Kabul, beat his father and accused H.S. of being a spy for the U.S. military, he said. They searched his room and left letters with his father, reviewed by The Times, ordering him to appear for a hearing at a local police department.

In letters of recommendation included in an appeal last year, H.S.' supervisors said he should receive a new security screening or have his SIV application approved. One Air Force reservist who worked with H.S. on a daily basis wrote that he was present the day of his counterintelligence screening and questioned the validity of the decision. H.S. "is a trusted and loyal friend, and I would put my own security clearance on the table to vouch for him,” he wrote.

Despite the entreaties from his supporters, H.S.' appeal was denied in December based on his termination. Two of his brothers were granted special immigrant visas years ago and live in Houston. One of them, A.S., whom The Times is identifying by his initials to protect H.S., worked as an interpreter at Ft. Bliss in El Paso, where thousands of evacuated Afghans were temporarily housed. There he learned what federal officials later acknowledged: About half of the 87,000 Afghans who were evacuated to the U.S. don’t qualify for SIV and most will need to apply for asylum to remain long term.

"Many of the translators who worked shoulder to shoulder with the U.S. government have been left behind, including my brother," he said.

Gerald Parks, a retired Army command sergeant major and president of Parks Global Solutions, a labor and logistics subcontractor, said he had no choice but to fire H.S. after his failed security screening. Parks said he has never been given the reasoning behind any counterintelligence decision.

But he said he trusts that the U.S. government wasn’t failing people without reason. He said 300 other former employees who were never terminated are still stuck in Afghanistan and he is trying to help them get out.

Parks said all of his Afghan employees, including H.S., were vouched for by people in positions of power before being hired. In his company’s 15 years in Afghanistan, he said, fewer than 20 of his approximately 600 interpreters were terminated because of a failed security screening or other disciplinary action.

“My heart goes out a little bit to the guy because he has contacted me several different times,” Parks said of H.S., adding that he "needs to go through another way of getting out and getting to the U.S. SIV is not going to get him there, not through me anyway.”

Internal State Department communications received by the International Refugee Assistance Project last year as part of a lawsuit over SIV processing delays shed light on how the agency has handled applications by terminated employees.

In a Feb. 4, 2014, email, Debra Heien, then-consul general of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, said the State Department’s Afghanistan chief of mission committee did not investigate the reasoning behind terminations beyond reviewing HR records and recommendation letters. In an email a year later, an SIV manager said applicants who were terminated for cause were historically denied approval. To appeal, the applicant must first "resolve the dispute with their employer."

A few months later, Consul Ian Hillman at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul sought feedback on a draft standard operating procedure for determining "faithful and valuable service." The document explains that special immigrant visas typically require at least 15 years of employment, but because the Afghan program requires only one year, it’s harder to prove someone met the requirement if their record includes disciplinary actions.

“Therefore, applicants who have been terminated from their employment typically do not qualify as having provided faithful and valuable service,” the document states.

The issue comes down to whether the applicants had “derogatory information” associated with their case and whether they were terminated for cause. People who were terminated and later rehired could meet the requirements for special immigrant visas if they work at least another year, the document states.

A State Department spokesperson said that while being terminated for cause was previously grounds for a "fairly automatic" denial, that's no longer the case. But IRAP and other advocates tell The Times they've noticed no changes.

Successful appeals are rare. Applicants must build a strong record of corroborating evidence and get additional recommendations from former supervisors, said Lara Finkbeiner, a pro bono supervising attorney at IRAP. Polygraph or broader counterintelligence screening failures are “next to impossible to overcome,” she said.

In March, Abdul Nasrat “Lucky” Sultani, 33, submitted his second application with 11 recommendation letters. He made it out of Afghanistan on an evacuation flight on Aug. 24, 2021, with his wife, four children, brother and two sisters.

Sultani's nickname was given to him by U.S. Marines for surviving multiple insurgent attacks while he was employed by Mission Essential, one of the largest companies supplying interpreters in Afghanistan that received billions of dollars in government contracts. Once, he said, the Taliban shot him in the back, breaking two ribs.

After three years as a combat interpreter, he was fired in 2013 because a position was no longer available, according to Mission Essential. Later the military reported him as being “security ineligible" based on his counterintelligence screening.

Kristina Messner, a spokeswoman for Mission Essential, said that terminations for security ineligibility took place when the federal government asked the company to fire an employee or when the employee failed a counterintelligence screening.

"Even if an employee was terminated, for any reason including security, ME still provides them with a letter to confirm employment," Messner said. "If the reason listed on the letter of employment is disputed by the linguist, we manually review all files on record for that individual thoroughly."

Sultani said that after he and others were questioned about a workplace incident, he was initially told he would be reassigned. According to a recommendation letter he later received from a military supervisor, “Lucky had no part in the incident.”

But Sultani learned his security clearance had been revoked when he applied for another job working with U.S. troops. He joined the Afghan national army instead.

Before leaving Afghanistan, Sultani said he volunteered with the U.S. government to evacuate more than 160 other vulnerable families. He said the Taliban sent threatening letters and visited his family’s home, warning that “soon it will be our turn.”

Sultani's former military supervisors wrote that he was committed to the U.S. mission and navigated his work with sensitivity. He interpreted in English, Pashto and Dari while his platoon built schools, searched people during raids and worked to cut the opium trade.

Former Marine Sgt. Jay Foley said locals would call Sultani to warn about ambushes, which saved countless lives. Foley said he would trust Sultani with his own life then and now.

Denying him a visa is "like not taking care of a veteran at the VA," Foley told The Times. "That dude was [basically] a Marine."

Sultani’s lawyer bought a house in Sacramento for him and his family to live in, rent-free. They spent months awaiting processing in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, before landing in California in June. His children started school in September, and Sultani is waiting for his work authorization so he can find a job. For the first time, he feels safe.

On Tuesday, Sultani learned he had received chief of mission approval — the biggest hurdle in his visa application. The moment was a dream come true.

“I worked with the Marines and they never forgot about me," he said.

Some interpreters got further along in the SIV process only to have their approval revoked. That’s what happened to M.O., 39, who worked on and off with U.S. forces from 2003 to 2014. M.O., whom The Times is identifying by his initials for his safety, resigned from Mission Essential in 2009 after speaking out about human rights abuses — including killings of unarmed civilians — by the clandestine unit he was working with that were later chronicled by the Guardian and the New York Times.

M.O. said in his SIV application that as he resigned, the supervisor in charge of the unit told him, "If you leave this room I will shut every door on your face." Years later, M.O. learned he had been flagged in a CIA database and was escorted off the military base near Jalalabad where he was working, according to the application.

After the State Department revoked his approval, he submitted a new SIV application last year. But last month the agency said it had no record of his application and asked that he resubmit.

Still in Afghanistan, M.O. said he grew a long beard to blend in and moved with his family 20 times in the last five years. His children are home-schooled and they barely leave their home. Now without a job, he hasn't paid the last four months of rent and said his landlord planned to evict them.

"I spent my whole adult life working for the U.S. military," he said, "and then I was a bad guy."

Other interpreters escaped to countries where they don’t have a direct path to citizenship.

Abdulhaq Sodais, 31, arrived in Germany in 2018 after seven months of grueling travel with smugglers. He fled Afghanistan after his neighbor, a fellow interpreter, was killed by the Taliban at his home.

Sodais had been rejected for SIV four times after working more than two years collectively for Mission Essential. In 2013, he was terminated for job abandonment — he said he declined to take a dangerous, Taliban-controlled road to return to the base in Zabol.

After he was rehired in 2014, Sodais was fired again in 2016 for poor job performance. The civilian defense contractor who fired him wrote in employment paperwork that he had an “incompatible skill set with [the] unit’s mission.” Sodais said she falsely accused him of checking his Facebook account at the office. Mission Essential said it has no record of the incident.

Sodais’ first German asylum claim was rejected. In 2020, depressed and overwhelmed by fear of deportation, he attempted suicide. At a psychiatric hospital, he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

He messaged his friend, U.S. Army veteran Spencer Sullivan, who vowed to help. Sullivan said he had been racked with guilt after the Taliban killed another interpreter who worked with the platoon he led until 2013.

Sullivan flew to Germany to help Sodais prepare for the asylum hearing. Last year, Sodais' petition was granted. The case will be reviewed in 2025 to determine if he qualifies for a permanent "settlement" permit.

Though Sullivan is happy his friend is safe, he feels powerless to help other Afghans he knows who are still in danger.

“It’s been a waking nightmare for the last decade," he said. "I have good days and I have really bad days because the weight of it becomes too much sometimes."

Sodais said that feeling abandoned by the U.S. was like a death sentence. Despite that, he would still welcome an opportunity to immigrate to the country he served.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.