Blacks were kept out of nice Modesto neighborhoods. ‘Not by error, but by plan’ | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A few decades ago, a young doctor saw a nice-looking home for sale in a north Modesto neighborhood he thought would be perfect for his future family. When he tried to buy it, he was told it had already sold.

But it hadn’t. In fact, the vacant house had been on the market more than a year.

Why was he turned away? It wasn’t for lack of earning potential. The physician had just finished residency at what was then Scenic General Hospital and was opening a practice in town.

Opinion

At that time, however, the neighborhood was composed exclusively of whites. Something Dr. Jesse Stovall was not.

“You see what’s going on,” Stovall told me in an unpublished interview in mid-2020, about 18 months before he died. “No need to investigate it. You have proof after proof. It happened. They wanted no Blacks to move into this area.”

In the 1950s, Sterling Fountain’s grandmother viewed a Modesto property under cover of darkness, Modesto View magazine quoted her as saying in a February 2020 article. “The neighbors would not have been able to accept the shock of seeing the first Black family having the possibility of living on their street,” Fountain said, according to writer Tasha Wilson.

The family bought the place, and upon moving in, neighbors assumed they were the hired help. Faced with the truth, “the whole street got together and financially offered her the amount she paid to purchase the home, in order for her family not to move in. She refused,” the article said.

In 1966, a white landlord refused to rent a Modesto duplex unit to a young Black couple even though both had steady jobs. “The owner said the lady on the other side of the duplex wouldn’t be comfortable living next to us — and she was on welfare,” the Black woman told me.

As Dr. Stovall said, proof after proof. It happened.

In the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s housing segregation was sanctioned by the government, a regrettable and racist practice I’ve written about before.

“No part of said real property shall ever be occupied at any time by any person or persons not of the white or Caucasian race,” read one template for recorded documents back then. “No Negroes, Mexicans, Hindus, Filipinos” was standard verbiage. Others targeted Turks, Armenians, Cubans, Hawaiians, Chinese, Japanese and other “Asiatics.” Servants were allowed to work in the homes even if they couldn’t live in the neighborhoods themselves.

This dark chapter in Modesto’s history comes alive in “Just Action; How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law.” Chapter 1 of the new book by Leah Rothstein and her father, Richard Rothstein, outlines the work done by Sharon and David Froba, who found that dozens of Modesto neighborhoods had barred people from buying thousands of homes simply because of the color of their skin.

Uncovering segregation in Modesto

The Frobas, both retired, felt driven to expose the scope of this ugliness persisting in official property records. They enlisted volunteers from student ranks at Modesto High School, where Sharon had taught, to scour documents recorded with Stanislaus County. Some of these students provided sobering comments for the Rothsteins’ book.

Clara Silva, for example, told the Rothsteins that “most people assumed (discrimination) was a Southern sin. To see that it was also in the North and in my home town, it was surprising to see how cancerous it was.”

Jobanna Peralta reflected in the book on the wealth lost by families of color, like hers, over many generations because they weren’t permitted to invest in homes whose value would compound over the years. “We people of color are kept in a box, a box that we can’t escape because it ties back to many, many years ago and the chain just keeps on going,” Peralta is quoted as saying.

Proof after proof, indeed.

The vestiges of discrimination can be seen in west and south Modesto, where some neighborhoods lack basic amenities like sewers, sidewalks and street lights. All are in unincorporated islands, or noncity areas surrounded by Modesto but never annexed because their infrastructure doesn’t meet city standards. Kids walking to school still slog around huge mud puddles. Residents are mostly brown and Black.

Government officials all these years have known of the disparity. They’ve shrugged it off because improvement costs are almost unbelievable, exceeding $700 million, Stanislaus County CEO Jody Hayes said. Lawsuits brought little relief because the county, which is responsible for these unincorporated islands, can’t come up with that kind of money.

Many times in my 30 years at The Modesto Bee have I written about the inequity, with little hope of ever seeing it corrected.

Friends, it’s time to recognize a positive shift.

When the county received $107 million in COVID-19 relief, supervisors voted to put $50 million of it toward righting some of the wrongs in these underserved neighborhoods, as well as others in places like Ceres, Turlock and Riverdale Park, many of which will get infrastructure upgrades.

When the county budget ended in the black last year, supervisors decided to put $15 million more into these disadvantaged neighborhoods.

As a result, crews are breaking ground on long-awaited drainage and sidewalk improvements in some of these challenging areas, including the Bret Harte and Parklawn neighborhoods of south Modesto near Crows Landing Road, in Board Chairman Channce Condit’s district, the most neglected in the county. “It’s monumental. A lot of people can’t believe it’s happening,” he told me recently.

More than 1,000 neighbors and local leaders signed petitions supporting an additional $5 million in state money secured a few weeks ago with help from Sen. Marie Alvarado-Gil.

Silver lining to COVID-19

As heartbreaking — and in many cases, life-ending — as the pandemic was, we should recognize this silver lining.

Although $70 million is only 10% of the $700 million needed, it’s a decent start, and it’s worth celebrating.

Condit and his colleagues on the board — Vito Chiesa, Terry Withrow, Mani Grewal and Buck Condit (Channce’s cousin, once removed) — might easily have found other uses for that money, as their predecessors always did. But this board correctly decided that these underprivileged neighborhoods had waited long enough.

As long as we’re giving credit where it’s due, let’s resume the story that started this column, because it has a happy ending. Although Dr. Stovall was stonewalled in buying the home he wanted in Modesto’s Sherwood Forest neighborhood, he didn’t give up.

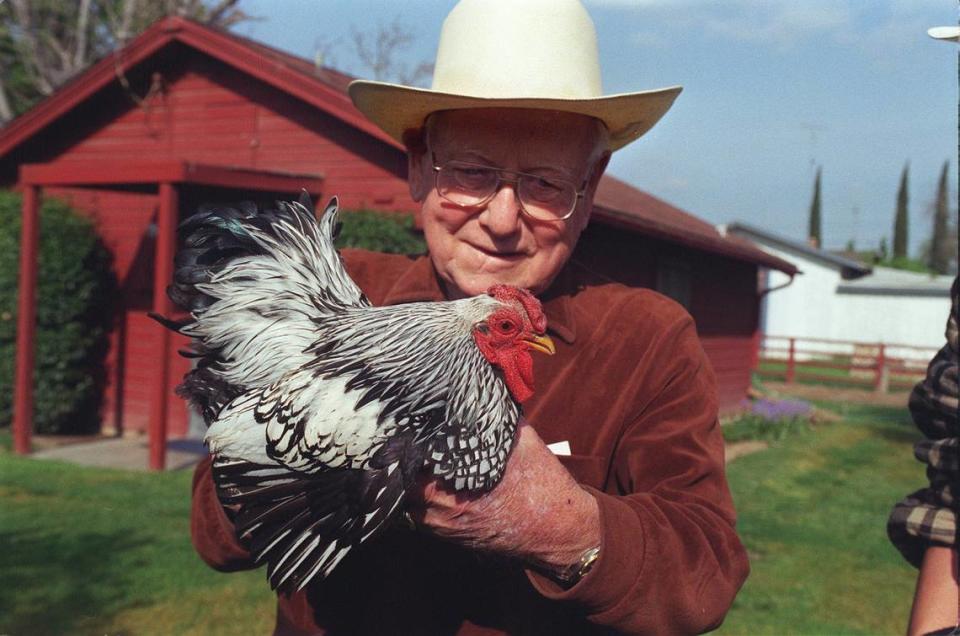

Eventually, Stovall enlisted the help of Gordon Nutson and Wolverine Real Estate, which he owned with his brother Gale and partners Howard TenBrink, Rudy Potochnik and Gilbert Grover. They were known for their willingness to help when other agents would not. Gordon Nutson made the sale happen. And, he loaned Stovall the money he needed for a down payment.

“That’s a fact,” Stovall told me in 2020. He lived 30 years in that house, and he died in early 2022, 20 years after Nutson died.

Stovall was keenly disappointed at policies hurting Blacks “not by error,” he told me, “but by plan.”

Nutson, it seems, was something of a hero to low-income buyers and nonwhites, working to help them overcome “the plan,“ according to a Bee profile a couple of years before he died by my former coworker, Jack Doo.

Combating bigotry and bias

“In the early days (he began selling houses in Modesto in 1947), we were the only office that would talk to, listen to, visit and help (them) buy homes,” Nutson told Doo in 2000. “No other real estate person would pay any attention to them.” Selling to a buyer who wasn’t white nearly got him kicked out of the local realty association in the early ‘50s, Doo wrote.

Proof after proof. It happened.

The world needs more Gordon Nutsons.

“He did things that in those days were not considered proper, selling houses to African Americans,” recalled Marianne Villalobos, whose family was close to Nutson’s. “When it came to civil rights,” she said, “he was a fighter all his life.”

Incidentally, Villalobos — like Sharon Froba, a Mo High teacher — was the first to discover race-based covenants on her deed. She shared them with the Frobas, whose work is memorialized in “Just Action.”

Based on similar efforts, the California Legislature last year required that clerk recorders in the state’s 58 counties begin reviewing all property records to redact shameful passages. That’s 6 million documents in Stanislaus alone, and some counties may need longer than the 2027 target deadline.

Yes, we have proof after proof that it happened. But we also have examples from people like Nutson, Villalobos and the Frobas, standing for right and showing us how to overcome bigotry and bias.