Block Island could have been 'the next Lahaina' during hotel fire. How downtown was saved.

NEW SHOREHAM — There was a persistent beeping.

Renee Reed assumed it was a cellphone. She and her husband, Chris, were settled in for the night in Room 218 of the Harborside Inn, just above the hotel's kitchen. They had a friend’s wedding at the Spring House the next day.

Then, an alarm sounded. She flicked on the lights. Smoke was filling the room.

“Get up,” she told her husband. “There’s a fire.”

It was just before 11:30 p.m. on Aug. 18, and fire was rapidly spreading unseen through the Harborside Inn.

Kristen Hutton, returning home from dinner with friends who serve on the island's all-volunteer fire department, saw one call: the Harborside Inn was on fire. At first, she wasn’t concerned — surely the firefighters would put out the blaze before it spread to the Mad Hatter, her store on the ground level.

“It’s bigger than you think,” her friend told her. “You should come down here.”

'You just had the sense it was going to be the one'

Block Island Fire Chief Chris Hobe was awake, 2½ miles away, down Corn Neck Road, when the box alarm came in at 11:23 p.m. Often, they turn out to be nuisance calls, but the dispatcher told him someone had seen smoke on Water Street.

This felt different.

John Breunig, superintendent of the Block Island Water Company, had the same instinct.

“I just knew I had to get there,” he said. “Something about that call, you just had a sense it was going to be the one.”

Hobe arrived on Water Street within four minutes. Smoke was pouring from an exhaust fan on the first floor.

“It had been burning for a while in the walls and up to the attic,” Hobe said of his initial assessment.

Soon, smoke was pushing out of the eaves. At 11:52 p.m., Hobe sent through a second alarm, signaling mutual aid – the first time ever on Block Island.

“We had a 20-man operation,” he said. “We needed 100.”

If the fire jumped to the other Victorian-era wood-frame buildings lining Water Street, it could easily destroy Block Island’s historic downtown. It was the very scenario Hobe envisioned when he spent the previous winter working with mainland fire chiefs and stakeholders on the island to formulate the island’s first mutual aid plan. He had no idea how soon he’d need it.

Block Island's downtown: Picturesque but highly combustible

Harborside Inn, with its welcoming porch set in the center of the picturesque streetscape, served, in many senses, as a gateway to the island for visitors.

Originally known as the Pequot House, it later became the Royal Hotel. Accounts differ on whether it was first built in 1879. There are tales it once held a brothel and a topless bar — notions that some firmly refute.

“If it had been a brothel, I think it would have been, frankly, in a lot better shape in the ‘60s,” said Martha Ball, a lifelong islander and member of the Block Island Historical Society board.

“Block Island is a place where rumors swirl like whirlpools and the truth stretched thin over time isn't going to hold up in court,” added Marc Scortino, who co-hosts the popular “Two Guys on Block Island” podcast and briefly ran the restaurant inside the hotel.

But when he’s asked locals if they ever went to the old Orchid Lounge at the Royal, he added, he’s observed a gender divide: Men over the age of 60 give him “a sly, knowing smile,” and women look aghast.

“It was a hotel with a bar, so who knows what happens,” Ball said, but she recalled long-ago warnings to young women to walk on the other side of the road.

Today, the ornate 19th-century hotels and restaurants clustered along Water Street are a major part of Block Island’s charm. They can also be highly combustible.

Like other structures of its era, it was constructed of “balloon framing,” a popular building style in the 1800s in which 2-by-4 studs were placed at intervals up the height of the building. Though it saved on lumber costs, no fire breaks existed between floors.

A fire could start in the basement and quickly travel up the walls to the attic. When Hobe and other volunteer firefighters arrived on the scene, that was already happening. The fire had quickly reached the attic, above any sprinkling lines.

Buying a little bit of time

The Reeds, who live in Madison, Connecticut, were the first guests to make it down to the Harborside’s lobby.

Chris made sure that Renee was safely out of the building. “Once my wife was out, I just turned around,” said Chris, a retired deputy fire chief in West Haven.

Reed directed guests gathering at the top of the stairs to leave while he and Block Island Police Cpl. Thomas Pennell grabbed fire extinguishers and went in to battle the fire in the kitchen.

Reed hoped to at least buy the firefighters some time. “Maybe it helped a little bit,” he said. “Once it got into the walls, it was a difficult operation.”

It didn’t take long for Block Island police and state troopers to make sure that all the guests were out, using a master key as they went from floor to floor. Block Island firefighters followed with a second sweep.

“They checked every room,” Block Island Police Chief John Lynch said. “That’s the only way you can be sure.”

'We were on the defensive'

Once they knew everyone was safely out of the building, firefighters focused on keeping the fire from jumping to neighboring buildings, some just feet away and already warm to the touch.

Adding to the concerns was the very real risk that they could run out of water: The island has 300,000 gallons of water storage, unlike mainland towns and cities, in which hydrants often have comparatively limitless draw. And from 13 miles offshore, it would take some time for help to arrive.

“We needed to control it," Hobe said. "We were on the defensive.”

The Block Island Volunteer Fire Department only has about 20 members who are very active. Twelve people initially responded to the Harborside fire, Hobe said, but the number eventually grew to more than 30.

Block Island Fire Deputy Chief Kirk Littlefield kept a hose on the flames at the back of the hotel, while some firefighters climbed on rooftops trying to get an interior attack. Hobe held command on Water Street, with water lines in place to protect Odd Fellows Hall to the south and New Shoreham House to the north.

A handful of junior members — including Hobe’s 14-year-old son, Zack — showed up to help. (Block Island’s fire department accepts junior members starting at 14, and lets them become full members at 16.)

So did dozens of other members, including Howell Conant, 71. He and Jacques Boudreau, a new 21-year-old member of the department, piloted an infrared drone to detect hot spots where temperatures were rising.

“It was a very key tool,” Hobe said. “We could direct suppression to the right spot.”

When the smoke grew so thick that firefighters couldn’t see where their water streams were hitting, Conant and Boudreau used two-way radios to tell the battalion chiefs where to aim.

Surveying the fire with the drone, which the department just purchased in June, was “like driving on a foggy night and having the fog stripped away,” Conant said.

An island comes together to help out

As word of the fire spread, vacationing firefighters from Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York showed up to see how they could help. FBI agents even arrived at the scene.

Calls went out to the island bars — the National, the Yellow Kittens, Captain Nick’s. Workers finished up their shifts and began pitching in.

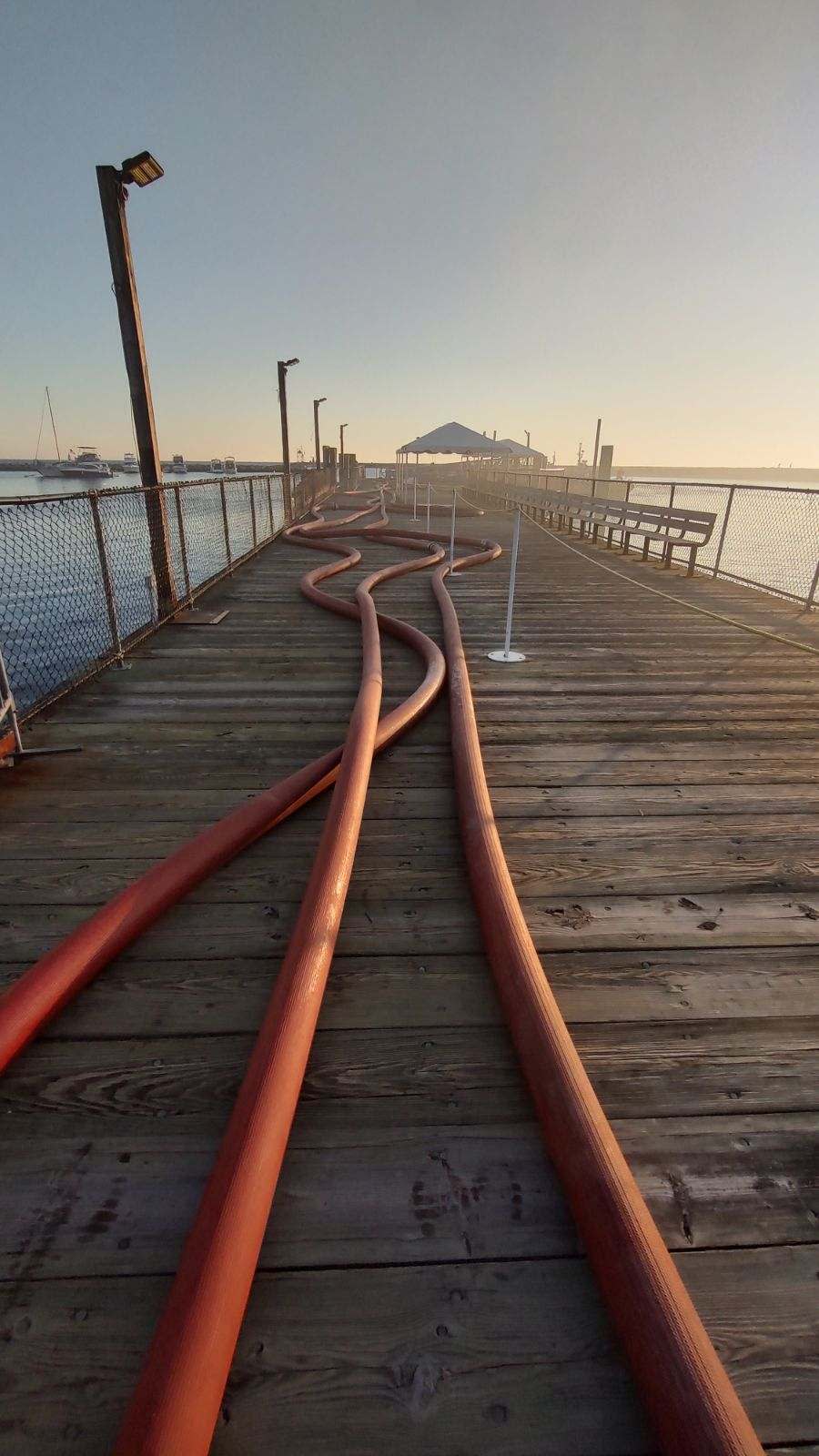

Onlookers helped the firefighters drag lines down to Old Harbor so they’d be ready to draw seawater when the time came. Others hurried to move propane tanks that fed nearby hotels and restaurants.

“They were literally rolling them down the street like bowling balls,” said Chris Crawford, the director of the Block Island Chamber of Commerce, who’d rushed down to Water Street with his wife, Town Manager Maryanne Crawford. “The firefighters were so busy fighting the fire that other people had to kind of jump in and help where they could.”

Stephen Papa, a co-owner of Aldo’s Bakery, helped wheel away scores of mopeds before their gas tanks could explode. Pennington Sprague Co. arrived with 240 gallons of diesel and refueled fire trucks throughout the night.

“It’s just what you do when you are out here,” said Cynthia Geer, who owns the company with her brother, former Fire Chief Joseph Sprague.

Hutton, the owner of the Mad Hatter, watched the fire burn for nine or 10 hours. She left only to pack a bag and gather valuables because there was a risk that her home would burn, too.

“We were in shock, of course, watching our livelihoods completely crumble,” she said. But at the same time, she said, she felt immensely grateful that everyone had gotten out of the hotel, and she was overcome with awe as she watched so many people work together to save the town.

“It was a total mix of emotions,” she said. “My jaw dropped the entire time.”

'You're not kidding me, right?'

When his phone rang at 12:23 a.m., Chris Myers, the Block Island Ferry’s port captain, was asleep at home in Portsmouth.

His first thought, when he saw “Town of Narragansett Emergency Services” flashing on the caller ID, was that something had gone wrong with one of the boats tied up in Point Judith. But the dispatcher was telling him that a hotel on Block Island was burning, and they needed to get as many fire trucks out there as possible.

“You’re not kidding me, right?” Myers said. Just seven minutes later, he was dressed and out the door, telling his wife and children that he’d explain later.

Hobe had requested mutual aid at 11:52 p.m., less than half an hour after arriving at the fire, setting the still draft plan in motion. At midnight, a call went out to New England Airlines, the Westerly-based airline that has served the island for more than 50 years. Before long, two planeloads of firefighters were making the 12-minute flight out to the island, chief pilot Sue Cowley said.

Other firefighters headed to Point Judith and were transported to the island by U.S. Coast Guard vessels. Marine Task Force fireboats that would help pump water prepared to make the journey from Newport, Narragansett and North Kingstown.

But the firefighters also needed more equipment, especially more ladder trucks tall enough to dump water on the three-story hotel. They would have to arrive by ferry. As he got in his car, Myers assured the dispatcher that they’d be on the way soon.

“That’s the best news I’ve heard so far,” she responded.

Speeding through the darkness, Myers dialed one number after another, trying to pull together a skeleton crew. On June 19, firefighters from North Kingstown and Narragansett held a practice run to map out how to pack the ladder trucks on the ferry boat.

There also was no time to spare: The 13-mile journey out to the island would take about an hour, and that wasn’t counting the time it would take to start the boat’s engines, back it up to the dock, and load it with fire trucks.

“A boat’s not like a car,” security officer Bill McCombe pointed out later. “You don’t just turn a key.”

As he raced down to Point Judith, Myers formulated a plan with port engineer John Tally, who lives just two minutes from the ferry terminal in Galilee. Tally would ready the M.V. Block Island so that Myers could drive it out to the island, then get the M.V. Anna C. running and follow him. At the same time, M.V. Carol Jean would head from the island to the mainland to free up dock space.

By the time Myers got to Galilee, fire trucks were already being loaded onto the boat, as were firefighters, including Providence fireman Reilly Hobe, Chief Hobe's 22-year-old son. At 1:30 a.m., Myers pulled away from the dock and began steaming toward Block Island.

“Everyone was hoping that the whole town wouldn’t catch fire before we got there,” he said.

The sea was slightly choppy once he got past the breakwater, and was lit up by the moon. Thick clouds of smoke billowing from Water Street got closer and closer as the boat neared Old Harbor, and Myers flipped on his searchlights before making the final approach.

“I remember thinking, 'I've never seen this before,'” said Myers, who has spent 34 summers working for Interstate Navigation. “And I hope I never see it again.”

Finally, some relief arrives from the mainland

It was 2:30 a.m. by the time the ferry reached the dock. Two large ladder trucks from North Kingstown and South Kingstown were the first to roll off. There was a palpable sense of relief: For hours, firefighters had fought to keep the blaze from spreading, and they’d held on long enough for help from the mainland to arrive.

More boats were on the way. By the time dawn arrived, three ferries delivered two ladder trucks, two engines, an incident command post and about 30 firefighters to the island. Seven firefighters from Westerly, Charlestown and Richmond, who could only bring uniforms and helmets because of weight restrictions, arrived on New England Airlines planes.

Throughout the night and into dawn, after the initial crews grew weary, Coast Guard cutters and fireboats delivered about 60 firefighters to the island. They came from 15 departments — Kingston, Bristol, Charlestown, Middletown, Narragansett, Newport, North Kingstown, Portsmouth, Richmond-Carolina, Westerly, Union Fire District, Dunns Corners, Misquamicut, Hope Valley and Jamestown.

Firefighters from Warwick, East Greenwich and Exeter ensured coverage in North Kingstown.

"Our goal was to get as many people over there as quickly as possible to give the Block Island firefighters some relief," North Kingstown Fire Chief Scott Kettelle said. He arrived at 1:39 a.m. aboard a Coast Guard cutter.

Kettelle and Hobe began talking about a year ago about devising a mutual-aid plan in the event of a major fire on the island.

"He gets all the credit. It's his foresight," Kettelle, president of the Rhode Island Association of Fire Chiefs, said of Hobe. "I just helped facilitate."

From plan to action

Across the winter, a coalition of departments from southern Rhode Island and even Connecticut met via Zoom to formalize a plan, exploring how response times and transportation methods would vary based on factors such as the time of day and sea and weather conditions. They brainstormed with state emergency management officials and the National Guard, Kettelle said.

In June, fire boats from North Kingstown, Newport, Narragansett and Groton, Connecticut, did a trial run to test response times and make sure their fittings connected with Block Island fire hoses, he said. A tabletop exercise had been planned for September.

"There's nothing we really would have changed," Kettelle said. "Our goal was to save the neighboring structures, and that's exactly what we did."

Town Manager Crawford recalls looking up at the dark sky and seeing airplanes approaching — something you’d normally never see in the middle of the night on Block Island. The other image that’s etched in her memory is the sight of the ferry arriving in Old Harbor, filled with firefighters who’d come to help keep the town from burning.

“There’s certain things from that night that will stay in my mind, and that’s one of them,” she said.

Emergency shelter opens up at the Block Island School

A mile from the fire, Chris Crawford and Tom Risom stood in the darkness, wielding a crowbar.

Truck headlights illuminated the FEMA trailer parked in between the Block Island Medical Center and the island’s only school for an emergency like this. Lacking a key, the two men tried to pry it open, but they only managed to bend the crowbar.

Risom, the town’s facilities manager, ran down and grabbed a sledgehammer off a fire truck. They forced their way in, pulling blankets, cots and hygiene kits out of the sweltering, pitch-black trailer.

The 75 guests evacuated from the Harborside now needed somewhere to go. Many were in pajamas, leaving behind shoes, wallets and car keys.

“All of the hotels on the island were completely booked,” said Crawford, of the Block Island Chamber of Commerce. “There was not one B&B room, not a hotel room anywhere.”

As the smoke intensified and the risk of the fire spreading grew, police also began evacuating people from neighboring buildings. Some bedded down in the lobby and bar of the National Hotel, which had set out blankets and pillows. Crawford opened the Block Island School — where he also serves as the athletic director — so its gym could become an emergency shelter.

A call went out to school bus driver Pat Evans, who immediately got out of bed and, within minutes, was shuttling stunned hotel guests up High Street to the impromptu shelter. Taxi drivers stopped collecting fares and focused on transporting people who’d been displaced.

Some had been out at the bars all night — “one guy literally upchucked all over the men’s room,” Crawford recalled — and others were crying. There were children who’d left behind stuffed animals, and at least two bridal parties who’d lost everything.

Still, Crawford said, “my big takeaway was how they were so appreciative and thankful.” To his surprise, everyone seemed to fall asleep by 4 a.m.

“At 7 in the morning, it was still deadly silent in there,” he said. “People were exhausted.”

'I knew I had to do something'

By the time the sun was up on Saturday, people all over the island were waking up to news of the fire and getting to work.

Alicia Miro, the owner of the Cracked Mug, was up at around 12:15 a.m. to give her dog his medication. Scrolling through Facebook, she saw photo after photo of the fire raging in Old Harbor.

“I knew I had to do something,” she said.

Instead of going back to bed, she headed to the bakery. By the time she received a text message from a fellow member of the fire department’s Ladies’ Auxiliary telling her they needed food, she was already pulling the first tray of muffins out of the oven.

As the fire raged, Miro brewed batch after batch of coffee for the firefighters. She prepared trays of bagels, baked cinnamon buns and at least eight dozen muffins, and made trip after trip to drop them off for the first responders and evacuees.

“Food and coffee are really the only ways I know how to help,” she explained.

Aldo's Bakery also opened up so that firefighters could use the bathroom, and handed out water, pastries and coffee. “We usually start baking at 2:30 a.m.,” Papa said. That night, they started a few hours earlier.

In the early hours of the morning, a small group that included councilmembers Neal Murphy and Molly O’Neill gathered at the fire barn and cooked enough egg sandwiches to feed dozens of first responders. As the day went on, more restaurants pitched in, donating sandwiches, pizza and hamburgers.

“There were so many of our local businesses that just said, ‘Go into the store and take what you need,’” Maryanne Crawford said.

At the shelter, local teenagers showed up around 3 a.m. and helped distribute cases of water. The next morning, there was food from The 1661 Inn.

Members of the Ladies’ Guild at St. Andrew’s Church, which runs a secondhand store, arrived with clothes and told displaced hotel guests to take whatever they needed. Renee Reed, who left her gown behind but still had a wedding to attend in a matter of hours, grabbed a pair of white Gloria Vanderbilt pedal pushers to wear with her black pajama top.

There were several weddings scheduled to take place on the island that day, and with morning ferry trips canceled, calls went out to find a plane or a charter boat that could transport an eight-piece band and string quartet.

One bride approached Crawford at the shelter and told him that everything — including her wedding dress — had gone up in flames. “What do I do?” she asked.

Locals found a dress she could wear and stitched it up to fit her perfectly. It wasn’t exactly traditional, Crawford said, but “it’s a wedding that they’ll never forget, I can guarantee you.”

Watching the water level

All night long, Breunig, the water company superintendent, had been closely watching how much water was left in the municipal supply.

He wasn’t just worried about having enough to put out the fire. Draining the tanks would force the town to issue a boil water advisory that would further hamstring hotels and restaurants at one of the busiest times of the year. Plus, no one would be able to flush their toilets until the system recovered.

“You have the competing interests of providing drinking water and fighting a fire," Breunig said. "You can’t fight a fire endlessly on a finite amount of water.”

Finally, at 3 a.m., he asked the firefighters to switch over to seawater, which can corrode equipment. It wasn’t ideal, he knew, but the alternative would mean creating a “secondary crisis.”

Chief Hobe would later estimate that firefighters had used about 3 million gallons of water to fight the fire. It took two full days for the system to recover, but the town never ran out.

'This wasn't dumb luck'

By noon on Saturday, the fire was largely extinguished. Some mainland firefighters were already leaving on the 10 a.m. ferry, where they were greeted with a round of applause. Boudreau and Conant remained on the scene with a small crew of firefighters until Sunday, monitoring for flare-ups.

The Harborside was a total loss. But, remarkably, no one was injured, and crews kept the fire from spreading to other buildings.

Miro, who’d started baking muffins for the first responders not long after midnight, finally left the Cracked Mug on Saturday afternoon and headed home.

Still feeling like there was more she could do, she created a fundraiser for the fire department on Instagram, with the expectation that it would raise a few hundred dollars. Within a week or so, it had collected more than $30,000.

A new ladder truck is due to arrive on the island in January, and Hobe hopes to raise $10 million, with assistance from the town, to build a station with seven bays. He believes a large pump station is needed in Old Harbor to better protect downtown.

Hutton left the fire and went home to sleep at around 8 a.m. on Saturday. When she woke up, she said, “It was like a nightmare. I got right out of bed to walk down there and see if it was real.” But she hadn’t been dreaming: The business she’d owned for 13 years had been destroyed overnight.

For weeks, the smell of smoke lingered on Water Street. Walking past the charred remnants of the Harborside, Hutton said, was like “walking past a ghost every day.” But she was also deeply grateful that the outcome of the fire had been ruined hats rather than lost lives.

If everyone on the island agrees on one thing, it’s that the fire could have been so much worse. They only had to look to the island of Maui, where wildfires had killed nearly 100 people the week earlier.

“The thing we always worried about was the domino effect,” Breunig said. “We’d be the next Lahaina.”

There were so many things that could have gone wrong. If the fire broke out during the day, Councilwoman Martha Ball pointed out that mainland firefighters and ferry operators would have been slowed down by beach traffic in Narragansett. If it had been winter, only one boat would have been running.

Other locals have their own “what ifs.” If the fire had started a few hours later, after the bars had closed, some hotel guests might have been passed out in their rooms and too slow to evacuate. If the winds had been blowing from the east rather than the west, ashes and embers would have blown onto neighboring buildings instead of the ferry parking lot.

If Chief Hobe hadn’t planned for a similar scenario, no one knows what might have happened.

“A lot of things fell in place here. This wasn’t dumb luck,” Breunig said. “It’s proactive thinking.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: How Block Island came together during the Harborside Inn fire