'A bloody business': Involuntary landmark designation attempts on rise in Fort Collins

When Jacqui Zipser and Holger Kley started house hunting in Old Town Fort Collins in early 2021, 323 S. Loomis Ave. checked all their boxes.

The quaint 1905 Queen-Anne-style cottage was tucked off of a quiet tree-lined street in Old Town — a neighborhood the couple had wanted to live in since moving to Fort Collins more than 20 years ago.

It was a short walk from Zipser's office and home to a pair of towering elm trees.

"And, frankly, the fact that it hadn't been updated in 50-plus years" was appealing to them, Kley said.

After looking at turnkey homes across Old Town in previous months, the couple ultimately set their sights on a fixer upper with plans to substantially rebuild or renovate one in their style.

The Loomis Avenue cottage fit the bill. Even its listing description seemed perfect.

"True fixer upper," the listing read, accompanied by photos of its weathered hardwood floors, outdated wood-paneled walls and aged sandstone-walled basement. "If you've been thinking of creating your own custom home in Old Town Fort Collins, this might be it!"

It wasn't that simple.

After buying the home that May, the couple decided to demolish it and build a new one in its place — a conclusion Zipser said the couple didn't reach lightly.

But shortly after settling on this plan, the home was nominated for historic designation against Zipser's and Kley's wishes, halting its proposed demolition and making 323 S. Loomis Ave. the latest subject of Fort Collins' recent uptick in involuntary landmark designation attempts.

The ensuing months were marked by a pair of hearings before Fort Collins' Historic Preservation Commission, the resignation of one of the commission's members and two big questions: What's behind the rising tide of involuntary designation attempts, and what do they mean for the future of historic preservation in Fort Collins?

There have been 4 involuntary designation requests, 3 of which came after years of none

To some, it started with 528 W. Mountain Ave.

After 135 years on its quiet Old Town corner, the little Folk Victorian home was sold in 2020 to a couple who planned to demolish it and build a new house in its place.

Given their big plans and the home's age — per national preservation standards, Fort Collins properties 50 years old or older can be considered for landmark eligibility — the public was notified of its proposed demolition.

Four community members stepped in to nominate it for preservation against its owners' wishes. According to current city code, a minimum of three Fort Collins residents are required to nominate a property for preservation without owner consent.

After months of publicized and, at times, contentious hearings, Fort Collins City Council ultimately rejected the Historic Preservation Commission's recommendation to landmark the home, clearing its pathway for demolition and construction of a new home in late 2021.

If the home had been landmarked, it would have been protected from any demolition or exterior alterations that didn't fit within national standards for historic properties. The home's owners would have also become eligible for state tax credits, a city-run zero-interest loan program and grants.

While impossible to say for sure, two members of the city's Historic Preservation Commission have theorized that — while it ultimately went undesignated — the review of the Mountain Avenue house could have been a catalyst in the recent uptick in nonconsensual landmark designation attempts.

"I think that people discovered that (the involuntary landmark designation process) was a way to maybe keep demolitions from happening that was potentially a very easy workaround with the current code," commission chair Kurt Knierim told the Coloradoan.

"That first one, 528 West Mountain, was one that I think kind of brought some attention that probably had either been latent or not even existent," Historic Preservation Commissioner Jim Rose also said.

Involuntary landmark designation attempts are exceedingly rare in Fort Collins and, to date, only one has been successful: Fort Collins' former post office building at 201 S. College Ave. was designated as a landmark against its owner's wishes when City Council swept in to save the property from demolition in 1985.

While involuntary landmark designation attempts have been rare as a whole, nonconsensual designation attempts on private homes were unheard of before 528 W. Mountain Ave., Fort Collins Historic Preservation Manager Maren Bzdek told the Coloradoan last year.

When the second-ever involuntary nomination on a single-family home came through for 323 S. Loomis Ave., Bzdek said she wasn't shocked. The little house is part of the Loomis Addition — one of Fort Collins' oldest and "preservation-minded" neighborhoods, according to Bzdek. Two homes don't make a pattern, however, she added.

"The pattern is that when there are enough individuals interested in that property, they’re going to come forward," Bzdek told the Coloradoan, later adding over email that while the city has seen two proposed designations for single-family homes after decades of not seeing them at all, "we can't yet know if that constitutes a trend."

Still, Fort Collins has seen three involuntary designation attempts and one owner-opposed historic eligibility determination in the two years since 528 W. Mountain Ave.'s failed designation.

Pobre Panchos eligible as a notable Hispanic business

Last summer, Pobre Pancho's Mexican Restaurant found itself in the middle of a designation attempt after its proposed demolition kicked off a historic review of the property, and city staff found it to be landmark eligible due to its longtime role in Fort Collins' Hispanic business community.

Family members of the restaurant's former owner nominated the building for historic designation against the current owner's wishes, kicking off a process that ended earlier this year when the Historic Preservation Commission made its final determination. While landmark eligible, the property was not historically significant enough to justify a nonconsensual designation, the commission concluded.

Quick Lube eligible for architectural style and commercial evolution

Also last summer, the historic review of another North Fort Collins property kicked off when Breeze Thru Car Wash filed preliminary plans to redevelop the Quick Lube on North College Avenue.

The Colorado Department of Transportation had previously determined two of the property's building's were eligible for the National Register of Historic Places following federally required planning work for the redevelopment of College Avenue back in 2010. When plans for the new car wash were submitted, the city conducted its own historic review and determined one of the property's structures, its former service station building located at 825 N. College Ave., was historically significant and eligible for landmark status by the Historic Preservation Commission.

Later, the commission twice found the building to be historically significant and eligible for landmark status based on its "classic example of ... the Oblong Box style of architecture" and the commercial evolution in north Fort Collins in the 20th century. The building has not been nominated for landmark status.

Because they're both commercial properties, Pobre Pancho's and Quick Lube's landmark eligibility determinations make the structures historic resources in the city's eyes — meaning that while redevelopment can still happen on both sites, it must incorporate the buildings into any future plans with few exceptions.

And then there was 323 S. Loomis Ave.

The saga on Loomis Avenue

After buying it in May 2021, Zipser and Kley had their work cut out for them. Their new home had cracks in its foundation, water damage, structural issues, a cigarette smoke smell that permeated throughout and the presence of asbestos in multiple living areas, according to their presentation to the city's Historic Preservation Commission during their second and final hearing on the nomination this March.

They originally planned to preserve the home's front façade and commissioned two designs that kept all or a significant portion of it while rebuilding the rest, Zipser said.

But because their home falls in Fort Collins' 100-year flood fringe — and no basement below the regulatory flood protection elevation may remain after any substantial improvement of a home, per city code — the couple had to abandon plans for keeping the home's existing basement, Kley said.

Without the additional square footage that its basement would have provided and a limited number of square feet the couple could build on the lot, also per city code, they went back to the drawing board. Ultimately, they decided against preserving the front façade because doing so would have dedicated "a significant portion of (the) entire living space to this front room that may smell like smoke regardless of what you do to it," Zipser said.

"At some point you just say, 'You know what? We’re going to cut our losses and go with a clean design,'" Kley added.

Demolition became their plan and, as with all Fort Collins properties 50 years old or older, a sign went up in front of 323 S. Loomis Ave. to notify the public.

Terri Berger — a Fort Collins resident who grew up in the home and whose mother owned it up until her 2021 death — along with Berger's husband and one more Fort Collins resident, nominated it for landmark designation, kicking off another involuntary landmark designation fight, much like the one that swirled around 528 W. Mountain Ave. two years earlier.

Zipser had kept tabs on the fight around the Mountain Avenue house and knew, because of that process, that an involuntary landmark designation attempt on their home was possible.

“But we also knew our house. We knew how utterly, well, dilapidated it was," Kley said.

In December, the Historic Preservation Commission voted 5-2 in favor of the home being landmark eligible due to its architectural features. As part of the nonconsensual landmark designation process, a second hearing followed three months later in which the commission considered whether the home was historically significant enough to outweigh its owners' objections.

The commission unanimously voted that it did not, ending the designation process.

At that final hearing, Zipser and Kley's attorney, Carolynne White, took issue with Berger being allowed to nominate the property after purportedly benefitting from its sale when her late mother's estate sold it to Zipser and Kley.

"This process can be weaponized," she told the commission at the March 22 hearing, noting that there are no rules laid out in the city code to prevent potential conflicts of interest when nominating potentially historic properties. "It really leaves an opportunity for mischief."

During that same hearing, Berger told commissioners she had hoped to nominate her childhood home for landmark designation while it was still in her family but was too distracted by grief in the wake of her mother's death. Berger declined to speak with the Coloradoan for this story.

"I would ask the commissioners to remember that their job is to preserve historical buildings," she said during the March 22 hearing. "I know that there has been much discussion around a non-owner designation, but my concern remains the same. Your job is to save historical properties. If you disagree with the municipal code, maybe you should challenge that."

As it turns out, they might.

Historic Preservation Commission member resigns, becoming disillusioned with how the process works

You don't join a historic preservation commission for the glory.

Unlike Fort Collins City Council meetings, which can fill City Hall and stretch well into the night, Fort Collins' quasi-judicial preservation commission toils away at its typically quiet meetings — mostly reviewing owner-supported landmark nominations and proposed exterior changes to existing historic properties through rules set out in the city code.

The all-volunteer commission discusses city floodplain regulations, pores over historic survey results and debates the merits of wood shingles versus synthetic roofing material on historic homes. Its meetings don't usually draw a crowd.

"They're more for insomniacs," joked Knierim, a longtime Rocky Mountain High School history and government teacher who joined the commission in January 2020.

But things are heating up for the commission as it finds itself in the middle of these involuntary landmark fights. As a result, changes to historic preservation rules laid out in the city's code may be coming down the pike.

"Certainly with the rise of (the involuntary landmark) process there's been more interest in our commission and what we do," Knierim said. "And there's been a variety of opinions on the commission itself."

"It's certainly been more spirited," he added.

In contrast, former chair Meg Dunn said her nine years on the Historic Preservation Commission — which lasted through 2022 when her second full term ended — were largely peaceful.

"In the beginning all the commissioners generally agreed. We were really good about, if we didn’t agree, talking it through until we had some kind of consensus. It was rare to have a split vote," she said.

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic began, after vacancies on the commission had piled up, "all the sudden they started (filling those vacancies) and we ended up with four brand-new people in a year," Dunn said.

The changing makeup of the commission soon coincided with its first nonconsensual landmark designation attempt on a private home — 528 W. Mountain Ave.

Fights over Pobre Pancho's, Quick Lube and 323 S. Loomis Ave. followed.

"I lost sleep. I literally ... I could not sleep on weeks we had a regular meeting," Dunn said, noting that her last year on the board was the most contentious in her experience.

Dunn particularly butted heads with Eric Guenther, a retired Ford Motor Co. marketing executive who had joined the commission in January 2022 after becoming interested in it following historic preservation attempts like the one on 528 W. Mountain Ave.

"Instead of sitting on the sidelines and criticizing, I wanted to contribute to historic preservation and learn more about the historic preservation process," Guenther told the Coloradoan.

Guenther and Dunn were both on the commission during the involuntary landmark designation attempt of Pobre Pancho's, the commission's first eligibility determination of Quick Lube's service station building and the first involuntary landmark hearing for 323 S. Loomis Ave. before Dunn's final term expired.

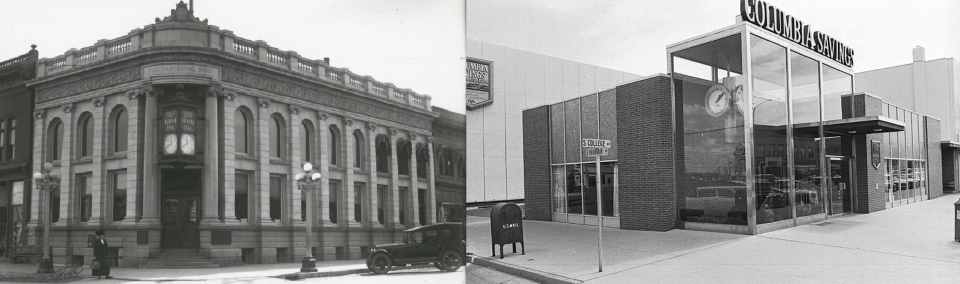

To Dunn, the recent rising tide of designation fights hearken back to what Fort Collins experienced in the 1960s, when a spate of potentially historic homes and buildings were razed to make way for new construction and parking lots. To many, the issue came to a head in late 1961, when Fort Collins' stately First National Bank building at College and Mountain avenues was torn down and later rebuilt as the modern, glass-walled Columbia Savings and Loan, historian Wayne Sundberg told the Coloradoan last year.

"Only (back then) we had no preservation code," Dunn said.

In 1968, two years after the National Historic Preservation Act was passed — establishing a federal and state preservation program to be administered by states in partnership with the National Park Service — Fort Collins City Council passed its own historic preservation ordinance. With it, the Landmark Preservation Commission, now the Historic Preservation Commission, was born.

Since 2018, 47 single-family homes 50 years old or older have been demolished in Fort Collins, according to city permit data. And with Fort Collins in a development pattern Dunn says is similar to the urban renewal of the 1960s, people are trying to fight the loss of potentially historic buildings like they did decades ago, she surmised.

In Dunn's eyes, the recent involuntary landmark designation attempts also show Fort Collins' municipal code working as intended.

“Any spurious (involuntary landmark) nomination is going to be thrown out at the first meeting," said Dunn, referring to the two-meeting system in place for involuntary landmark designation nominations. Properties wouldn't even reach that stage if they're not first determined to be historically eligible by the city's historic preservation staff, Dunn added.

At the first Historic Preservation Commission meeting of the involuntary designation process, the commission determines if the property has sufficient enough integrity and historic significance to be a Fort Collins landmark using standards laid out in the city code.

The second meeting is held later to determine if designation of the property supports the city's historic preservation policies enough to outweigh its owner's objections.

"Right there you’ve got two really strong guardrails to keep it from ever even getting to City Council. And then I’ve never seen any (involuntary landmark designation nominations) pass City Council," Dunn said. "That’s not just a guardrail ... It’s never happened.”

The involuntary landmark designation process was also tightened in 2014 when Fort Collins' municipal code was amended to require three Fort Collins residents to nominate a property against its owner's wishes. Before that change, only one Fort Collins resident was needed to kick off an involuntary landmark designation attempt, Dunn noted.

Unlike Dunn, Guenther said he became disillusioned with the city's historic preservation process as he sat through various involuntary landmark designation hearings and a contested historic eligibility determination as a commissioner.

The fights over Pobre Pancho's and 323 S. Loomis Ave. in particular, "really forced me to reevaluate the process, to see if it was fair, balanced and reasonable to the property owners as much as it was to the applicants," Guenther said.

For Zipser and Kley, the involuntary landmark designation process surrounding their home took roughly five months and cost them attorney and expert fees as well as property taxes, utility and maintenance costs as their home sat vacant and in limbo.

"If we could have cut this off after the first hearing, that saves us quite a bit of stress, time and money," said Zipser. "To get to a second hearing and have the commissioners vote 6-0 against recommending designation of this property. Well, that’s great and it feels like vindication, but we had to spend a lot of money to get to that point. Couldn’t we have addressed this at the first hearing?”

Guenther also took issue with the fact that any three Fort Collins residents can nominate a property against its owners' wishes, leaving space for former owners or family members of former owners to benefit from a property's sale and then force a monthslong nomination process onto its new owners. He said he believes the number of required nominators should be raised to at least 25 to represent a broader swath of the community.

The question of real estate agents' role in the sale of potentially historic homes also interested Guenther. While the city's historic preservation staff will be conducting a training for Fort Collins' Board of Realtors next month, real estate agents and sellers aren't required to inform a buyer about the city's involuntary landmark designation process, according to the Board of Realtors.

"If the city has a process for an (involuntary landmark designation), then, to me, a property that’s 50 years old or older should (come with) some kind of acknowledgement on behalf of the buyer to make sure they understand an (involuntary landmark designation) process could kick off," Guenther said.

This February, after a little more than a year on the Historic Preservation Commission, Guenther resigned from the commission over these qualms with the city's code. To Bzdek's knowledge, Guenther's resignation is a first of its kind for the Historic Preservation Commission.

While Guenther has "tremendous respect" for the city's historic preservation staff, he said he hopes the code can be amended someday to take property owner concerns more into account when an involuntary landmark designation is being considered.

"I got into this to preserve historic landmarks and the stories they tell in this city, and I don’t have a good pathway to do that now," Guenther said. "I was disappointed to resign, but with several votes where my vote felt constrained by the municipal code, I didn’t feel like I could vote in good conscience."

'Code cleanup process' is in the works

As the Historic Preservation Commission contends with more criticism, the uptick in involuntary landmark designation attempts and Guenther's resignation, Fort Collins' historic preservation office is anticipating "a code cleanup process" — and has for a number of months, according to Bzdek.

While no timeline is attached to these potential code changes, Bzdek said her office is in "informal outreach and engagement mode" with the community — tracking comments made to city council and the Historic Preservation Commission. Ultimately, Bzdek said she expects City Council to provide direction on the focus of any potential changes.

Knierim said the Historic Preservation Commission has been having conversations with city staff and giving feedback on potential code change recommendations.

"There are holes in the code where there is potential for misuse," Knierim said, noting that the biggest one, in his opinion, lies in the city's involuntary landmark designation process. "It's just so easy right now to get that process going. It opens itself up for potential uses that weren't intended in (the) code."

For Commissioner Rose, a retired architect, college professor and preservation consultant who joined the Historic Preservation Commission in early 2020, some added clarity to the code would be welcomed.

"So much of what we do is so subjective," Rose said.

“I think as we work through some of these other issues, we’re going to maybe have some suggestions about how some of this (code) language could be made more clear — not just so the commissioners have a stricter guidebook, but so the public understands how these decisions are made and how they’re arrived at."

When people hear about Historic Preservation Commission decisions, they typically aren't aware of the lead-up or background behind them, Rose added.

"These decisions aren't made in the moment. They're (made) with deliberation and background," he said. "I mean, good lord, we have 400-page packets."

After his career in architecture, preservation and education, Rose said he's no stranger to the contention that can swirl around historic preservation. It's not all quiet meetings, unanimous votes and friendly roof shingle debates — at least, it isn't anymore in Fort Collins.

The hubbub takes Rose back to his early years as an architect when a Venetian preservationist he worked with said something he's never quite been able to forget: "This," he said, "is a bloody business."

Coloradoan reporter Pat Ferrier contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Fort Collins historic designation: Involuntary nominations on rise