Bloomington's Banneker Center: A retrospective on the site's complex history

Editor's note: In honor of Black History Month, The Herald-Times is publishing Black stories, both current and historical, throughout the month of February. A new installment will be published each weekday.

While the Banneker Community Center is now known as a place for pick-up basketball and youth-led recreation, the site's over 100-year legacy on Seventh Street has some complicated affiliations to Bloomington's racial inequality.

The building was originally founded as a segregated school for African American children in the early 1900s. Before Banneker's opening in 1915, African American students went to another segregated school on Sixth Street.

The school was named after Benjamin Banneker, a free, Maryland-born Black man who lived in the 1700s. Banneker was a prolific scientist, having excelled in the fields of mathematics and astronomy despite the legal and societal barriers of his time. Through his published works, including his Astronomical Almanac, his prowess impressed Thomas Jefferson, who recommended Banneker for the surveying team platting Washington, D.C. Banneker was also a staunch abolitionist who repeatedly urged Jefferson and other contemporaries to spearhead civil rights.

When the newly christened Banneker school opened that December in Bloomington, it had three teachers and 93 students. At its peak, the school served 111 students from first through eighth grades.

While woefully underfunded and underresourced, Banneker's staff and board tirelessly sought to better the conditions for students, including raising enough funds to add a new gymnasium in 1942. This annex was actually used by the entire Bloomington community as Banneker, while still being a segregated education space, was opened to children of all ages and races for after school clubs and programs.

Indiana lawmakers put an end to legal segregation in 1949, with the state being among the last non-slave states to statutorily remove segregation. Under this legislation, Hoosier communities had until 1954 to integrate their school systems, coincidentally aligning with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education. While this is an accepted belief, some local historians say Banneker's near-future end as a school was also predicated on financial problems and declining enrollment.

School segregation in Bloomington ended in the 1951 school year when white students from Fairview Elementary were enrolled alongside Black students at Banneker for fifth- and sixth-grade classes. As noted by the Indiana Historical Bureau, integration did not go smoothly, leading to protests from some local citizens. Banneker only remained a school for a few more years until all students were transferred to the newly finished Fairview Annex school on Eighth Street.

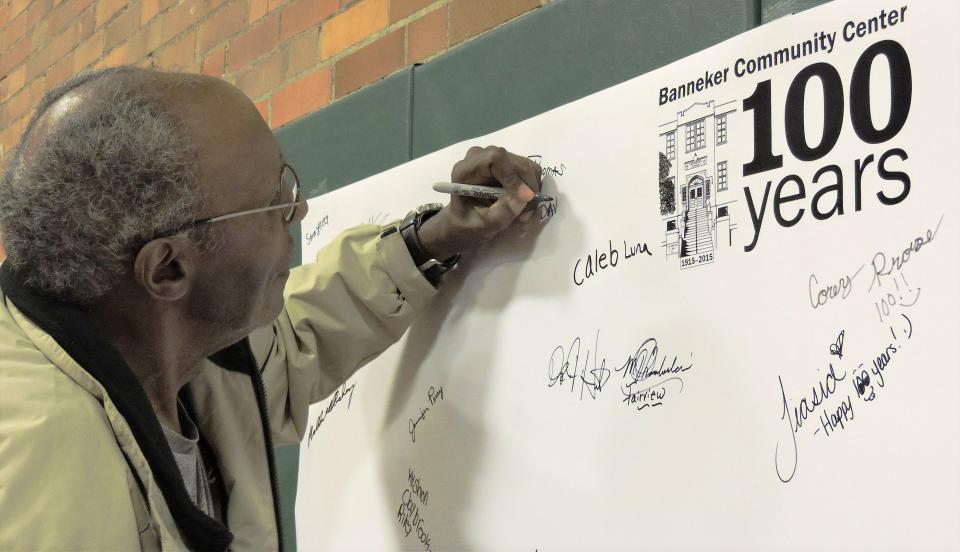

By 1955, Banneker was re-outfitted to solely focus on after-school recreation; it was rechristened as the Westside Community Center. In the early 1990s, the aging building went through a slate of major renovations while community members simultaneously floated the idea to better publicly acknowledge the site's history. In 1994, it was renamed the Benjamin Banneker Community Center.

Now Bloomington doesn't hide the center's past but rather uses it as a teaching device. In the early 2000s, Bloomington high school students participated in the Banneker History Project, where they collected personal accounts and empirical data to paint a clear picture of how racial segregation and inequality once permeated their own town.

An opportunity for more in-depth research into this history is still available for residents. The Monroe County History Center has collected oral histories from former Banneker students for modern audiences to have firsthand accounts.

In addition to its physical activity programs, Banneker also hosts the Evans-Porter Memorial Library, which offers fiction and nonfiction books for adults, teens, and children. The library has a focus on African-American history and culture, reflecting the library's location in a historically significant building and neighborhood.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Banneker Center in Bloomington, Indiana, was once a segregated school