With 'Blue Laws,' Labor Day's seasonal turn came to Columbus quietly in 1922

By the early part of the 20th century, Labor Day had become something of a hallmark in the lives of the people of America in general, and Columbus in particular.

The actual change of season from summer to fall takes place a bit later in September. But in the years after the full emergence of Industrial America, Labor Day had become a place in time of its own.

Then, Labor Day for many children was the last day of summer vacation − school started the next day. Today, most school districts begin classes in August.

Other places noted the change as well. Many outdoor swimming pools, public and private, closed for the season on that first Monday of September. Fall fashions often were touted after Labor Day by retailers large and small. Summer vacations were over and families had returned home. And politicians running for office began their final sprint in earnest to win elections coming in November.

And to begin all this transition, since the late 1800s, America had observed a holiday that came to be called Labor Day. It was a day to remember and celebrate the working people of America, and it did just that with parades, picnics and a lot of people making speeches of one sort or another.

In Columbus, Labor Day 1922 was celebrated a bit more quietly. World War I had ended in 1918, but it was not until Labor Day four years later that the last soldiers dismantling a major military base left Camp Sherman in Chillicothe. They were reassigned to Columbus Barracks, which would soon have its name changed to Fort Hayes.

Most residents of Columbus observed the holiday in other ways. A local newspaper reported on the activities of the day: “Labor Day in Columbus is being observed quietly. Stores are closed, there will be no parade and no mail deliveries. In general, things seemingly were under ‘Blue Law’ restrictions.

“The Columbus Federation of Labor will hold a celebration at Heimandale Grove, south of Columbus, with an old-fashioned barbecue and celebration. The speakers include F.P. Zimpfer, president of city council, councilmen Wehe and Worley, and M.R. Cain.

“L.C. 'Daddy' DeBloom, veteran of the local labor organization, is in charge of the celebration. Transportation to the Grove from the end of the Parsons Avenue street car line has been arranged. An ox roast, dancing and games are other features on the program.”

Perhaps a little explanation of “who, what and when” is in order. Readers at the time knew that the Columbus Federation of Labor was the local chapter of the American Federation of Labor. The Federation had been founded in Columbus in 1886. The United Mine Workers had been founded in the capital city in 1890. The groups were formed here because Columbus was an easy town to reach by railroad from almost anywhere in America.

Heimandale Grove was a privately owned gathering spot available by rental for group or social outings and family reunions. In an era before the widespread advent of automobiles, a number of these private parks were around the city. Most of them, including Heimandale Park, now are gone. As the growing city expanded, Heimandale Park became a residential subdivision in the south end of Columbus.

And then there are the “Blue Laws.” Originating in the colonial East, Blue Laws restricted activities permissible in local stores and by local organizations on Sundays, and in some places on other days as well. In particular, the sale of alcohol was prohibited.

Ohio had had Blue Laws in place at the state and local level since the 1830s. The restriction on alcohol in 1922 was understandable because a Constitutional amendment prohibiting its manufacture, sale and distribution had been in place since 1920. A Blue Law notice in 1922 might have indicated that a reminder was needed.

There is some speculation that the term “Blue Law” is derived from the usage of the word "blue" − meaning "distinctly moral" − and originated with Puritans in the 1700s. The laws usually were most repressive in Puritan communities and banned any sort of work on Sunday as well as buying, selling, traveling or sports.

H.L. Mencken, the irrepressible American critic, once observed that Puritanism was “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.”

Over the years, cultural changes led to the slow but sure limitation and eventual elimination of Blue Laws in Ohio. But it took a while.

Best for a pleasant and safe Labor Day to one and all.

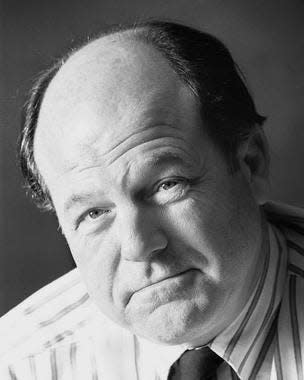

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes the As It Were column for ThisWeek Community News and The Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Labor Day had quiet seasonal turn in Columbus in 1922